Suzanne Valadon

Suzanne Valadon | |

|---|---|

Valadon as a young woman | |

| Born | Marie-Clémentine Valadon 23 September 1865 Bessines-sur-Gartempe, France |

| Died | 7 April 1938 (aged 72) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism, Symbolism |

| Partner(s) | Erik Satie, Paul Mousis, André Utter |

Suzanne Valadon (23 September 1865 – 7 April 1938) was a French painter and artists' model who was born Marie-Clémentine Valadon at Bessines-sur-Gartempe, Haute-Vienne, France. In 1894, Valadon became the first woman painter admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. She was also the mother of painter Maurice Utrillo.

Valadon spent nearly 40 years of her life as an artist.[1] The subjects of her drawings and paintings, such as Joy of Life (1911), included mostly female nudes, female portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. She never attended the academy and was never confined within a tradition.[2]

As a model Valadon appeared in such paintings as Pierre-Auguste Renoir's 1883 Dance at Bougival and Dance in the City, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's 1885 portrait.

Early life[]

Valadon grew up in poverty with her mother, an unmarried laundress in Montmartre;[3] she did not know her father. Known to be quite independent and rebellious, she attended primary school until age 11.

She also began working at age 11. She held various odd jobs which included: a milliner's workshop, a factory making funeral wreaths, selling vegetables, a waitress, and then finally the circus at the age of 15. She was able to work at the circus due to her connection with Count Antoine de la Rochefoucauld and , two symbolist painters, who were involved in decorating a circus belonging to Medrano. Her job position in the circus was a acrobat, however a year into working there she fell from a Trapeze ending her circus career. The circus was visited frequently by artist such as Lautrec and Berthe Morisot and this is rumored to be where Morisot did her painting of Valadon.[4]

It is commonly believed that Valadon taught herself how to draw at the age of nine.[5] In the Montmartre quarter of Paris, she pursued her interest in art, first working as a model and a muse for artists, observing and learning their techniques, before becoming a noted painter herself.[6]

Model[]

Valadon debuted as a model in 1880 in Montmartre at age 15.[7] She modeled for over 10 years for many different artists including Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes, Théophile Steinlen, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Jean-Jacques Henner, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.[1] She modeled under the name "Maria" before being nicknamed "Suzanne" by Toulouse-Lautrec, after the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders as he felt that she especially liked modeling for older artists.[8][9] For two years, she was Toulouse-Lautrec's lover until her attempted suicide in 1888.[10][2]

Valadon helped to educate herself in art by observing the artists at work for whom she posed.[2] She was considered a very focused, ambitious, rebellious, determined, self-confident, and passionate woman.[11] In the early 1890s, she befriended Edgar Degas, who, impressed with her bold line drawings and fine paintings, purchased her work and encouraged her; she remained one of his closest friends until his death. Art historian Heather Dawkins believed that Valadon's experience as a model added depth to her own images of nude women, which tended to be less idealized than the male post-impressionists' representations.[12]

The most recognizable image of Valadon is in Renoir's Dance at Bougival from 1883, the same year that she posed for Dance in the City.[13] In 1885, Renoir painted her portrait again as Girl Braiding Her Hair. Another of his portraits of her in 1885, Suzanne Valadon, is of her head and shoulders in profile. Valadon frequented the bars and taverns of Paris with her fellow painters, and she was Toulouse-Lautrec's subject in his oil painting The Hangover.[14]

Artist[]

Valadon was an acclaimed painter of her time, well respected and championed by contemporaries such as Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. She lived a bohemian life with rebellious vision.[15]

Valadon began painting full-time in 1896.[5] She painted still lifes, portraits, flowers, and landscapes that are noted for their strong composition and vibrant colors. She was, however, best known for her candid female nudes that depict women's bodies from a woman's perspective.[16] Her work attracted attention partly because, as a woman painting unidealized nudes, she upset the social norms of the time.[17]

Valadon's earliest surviving signed and dated work is a self-portrait from 1883, drawn in charcoal and pastel.[5] She produced mostly drawings between 1883 and 1893, and began painting in 1892. Her first models were family members, especially her son, mother, and niece.[18] Her earliest known female nude was executed in 1892.[19] In 1895, the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel exhibited a group of twelve etchings by Valadon that show women in various stages of their toilettes.[5] Later, she regularly showed at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris.[20] Valadon's first time in the Salon de la Nationale was in 1894. She also exhibited in the Salon d'Automne from 1909, Salon des Independants from 1911; Salon des Femmes Artistes Modernes, 1933-1938.[21] Degas was notably the first person to buy drawings from her,[22] and he also introduced her to other collectors, including Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard. Degas also taught her the skill of soft-ground etching.[23]

In 1896, Valadon became a full-time painter after her marriage to the well-to-do banker Paul Mousis.[5] She made a shift from drawing to painting starting in 1909.[24] Her first large oils for the Salon related to sexual pleasure, and they were some of the first examples in painting for the man to be an object of desire by a woman. These notable Salon paintings include Adam and Eve (Adam et Eve) (1909), Joy of Life (La Joie de vivre) (1911), and Casting the Net (Lancement du filet) (1914).[25] In her lifetime, Valadon produced around 273 drawings, 478 paintings, and 31 etchings, excluding pieces given away or destroyed.[26]

Valadon was well known during her lifetime, especially towards the end of her career.[27][page needed] Her works are in the collection of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Museum of Grenoble, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, among others.

Style[]

Valadon was not confined to a specific style, yet both Symbolist and Post-Impressionist aesthetics are clearly seen within her work.[28] She worked primarily with oil paint, oil pencils, pastels, and red chalk; she did not use ink or watercolor because these mediums were too fluid for her preference.[29]Valadon's paintings feature rich colors and bold, open brushwork often featuring firm black lines to define and outline her figures.[1]

Valadon's self-portraits, portraits, nudes, landscapes, and still lifes remain detached from trends and aspects of academic art.[30] The subjects of Valadon's paintings often reinvent the old masters' themes: women bathing, reclining nudes, and interior scenes. She preferred to paint working-class models. Art historian Patricia Mathews suggests that Valadon's working-class status and experience as a model influenced her intimate, familiar observation of these women's bodies. In this respect she differed from Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, who painted mostly women, but "remained well within the bounds of propriety in their subject matter" because of their upper-middle-class status in French society.[27][page needed] Valadon's marginalized status allowed her to enter the male domain of art through modeling, and her lack of formal academic training may have made her feel more comfortable breaking with convention.[31] She has been considered a transgressor as a woman painting the nude female body.[32] She resisted typical depictions of women via their class and supposed sexuality through her use of unidealised and self-possessed bodies that are not overly sexualised.[33] She also painted many nude self-portraits across the span of her career, the later of which displayed her aging body.

Valadon emphasized the importance of composition of her portraits over painting expressive eyes.[29] Her later works, such as Blue Room (1923), are brighter in color and show a new emphasis on decorative backgrounds and patterned materials.[34]

Personal life[]

In 1883, aged 18, Valadon gave birth to a son, Maurice Utrillo.[1] Valadon's mother cared for Maurice while she returned to modelling.[11] Valadon's friend Miguel Utrillo would later sign papers recognizing Maurice as his son, although his true paternity is uncertain.[35]

In 1893, Valadon began a short-lived affair with composer Erik Satie, moving to a room next to his on the Rue Cortot. Satie became obsessed with her, calling her his Biqui, writing impassioned notes about "her whole being, lovely eyes, gentle hands, and tiny feet", but after six months she left, leaving him devastated.[36] Valadon married the stockbroker Paul Mousis in 1895, living with him for 13 years in an apartment in Paris and in a house in the outlying region.[29] In 1909, Valadon began an affair with the painter André Utter, the 23-year-old friend of her son, divorcing Moussis in 1913.[37] Valadon married Utter in 1914,[5] and he managed her career as well as her son's.[38] Valadon and Utter regularly exhibited work together until the couple divorced in 1934.[38]

Feminist legacy[]

As one of the best documented French artists of the early 20th century, Valadon's body of work has been of great interest to feminist art historians,[39] especially given her focus on the female form. Her work was candid and occasionally awkward, often characterized by strong lines, and her resistance to both academic and avant-garde conventions for representing the female nude have encouraged interest in her work: It has been argued that many of her images of women signal a form of resistance to some of the dominant representations of female sexuality in early 20th-century Western art. Many of her nudes painted from the 1910s onwards are heavily proportioned and sometimes awkwardly posed. They are conspicuously at odds with the svelte, 'feminine' type to be found in the imagery of both popular and 'high' art.[31] Her self-portrait from 1931, when she was 66, stands out as one of the early examples of a female painter recording her own physical decline.[40]

Her first institutional exhibition in the U.S. will be held at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia in September 2021. She is now known to have been an important modern artist who, like many other talented female artists, has been under recognized.[15]

Group exhibitions[]

- 1894, Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Paris; 1907, Galerie Eugène Blot, Paris;

- 1909, 1910, 1911, Salon d'Automne, Grand Palais, Paris;

- from 1911, 1926 (retrospective), Salon des Indépendants, Paris;

- 1917, Utrillo, Valadon, Utter, Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris;

- 1920, Second Exhibition of Young French Painting, Galerie Manzy Joyant, Paris;

- 1921, Young Painting, Palais d'Ixelles;

- 1927 and 1928, Salon des Tuileries, Paris;

- from 1933-1938 and regularly, Salon des Femmes Artistes Modernes, Paris.

- After her death: 1940, 22nd Biennale Internationale des Beaux-Arts, Paris;

- 1949, Great Trends in Contemporary Painting from Manet to our Day, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyons; 1961, Maurice Utrillo V. Suzanne Valadon, Haus der Kunst, Munich;

- 1964, Documenta, Kassel;

- 1969, 14th Salon de Montrouge;

- 1976, Women Artists (1550-1950), Los Angeles County Museum of Art;

- 1979, Maurice Utrillo, Suzanne Valadon, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec,

- Albi; 1991, Utrillo, Valadon, Utter, Chateau Constant, Bessines

- 1991, Utrillo, Valadon, Utter: la Trilogie Maudite, Acropolis, Nice.

Solo exhibitions[]

- 1911, the first, at the Galerie Clovis Sagot;

- 1915, 1919, 1927 (retrospective) and 1928, Galerie Berthe Weill, Paris;

- 1922, 1923 and 1929, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris;

- 1928, Galerie des Archers, Lyons;

- 1929 and 1937, Galerie Bernier, Paris;

- 1931 and 1932, Galerie Le Portique, Paris;

- 1931, Galerie Le Centaure, Brussels;

- 1932, retrospective with a preface by Édouard Herriot, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris.

- 1938, 1942, 1947, 1959 and 1962, Galerie Pétridès, Paris;

- 1939 and 1947, Galerie Bernier, Paris;

- 1948, Tribute to Suzanne Valadon, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris;

- 1956, The Lefevre Gallery, London;

- 1967, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris;

- 1996, Suzanne Valadon, Pierre Gianada Foundation, Martigny.

- 2021, the Barnes Foundation will present the first major US exhibit of Valadon's work.[41][42]

Permanent collections[]

- Albright-Knox, Buffalo[43]

- British Museum, London[44]

- Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh[45]

- Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas[46]

- Detroit Institute of Arts[47]

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco[48]

- Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge[49]

- Indianapolis Museum of Art[50]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art[51]

- Minneapolis Institute of Art[52]

- Musée d'Unterlinden, Colmar[53]

- Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon[54]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston[55]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York[56]

- National Museum of Women in the Arts[57][5]

- Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City[58]

- Petit Palais, Geneva[59]

- Rose Art Museum, Waltham[60]

- Smart Museum of Art, Chicago[61]

- University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor[62]

Death[]

Suzanne Valadon died of a stroke[63] on 7 April 1938, at the age of 72, and was buried in Division 13 of the Cimetière de Saint-Ouen, Paris.[64] Among those in attendance at the funeral were her friends and colleagues André Derain, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque.

Novels and plays[]

A novel based on the life of Suzanne Valadon was written by Elaine Todd Koren and was published in 2001, entitled Suzanne: of Love and Art.[65] See also Suzanne Valadon. An earlier novel by Sarah Baylis, entitled Utrillo's Mother, was published first in England and later in the United States. Timberlake Wertenbaker's play, The Line (2009), traces the relationship between Valadon and Degas. Valadon was the basis for the character Suzanne Rouvier in the novel The Razor's Edge by W. Somerset Maugham.[66]

Honors[]

Both an asteroid (6937 Valadon) and a crater on Venus are named in her honor.

The small square at the base of the Montmartre funicular in Paris is named Place Suzanne Valadon. At the top of the funicular, and less than 50 meters to its east, are the steps named rue Maurice Utrillo after her son the artist.

Gallery[]

Artwork by Valadon[]

Self-Portrait, 1883

Portrait of Erik Satie, 1893

Nude, 1895

Women, c.1895

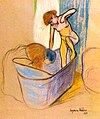

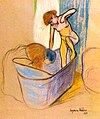

The Bath, 1908

Nudes, 1919

Flowers on a Round Table, 1920

Portrait of the Painter Maurice Utrillo, 1921

The Blue Room (La chambre bleue). 1923

Still Life with Tulips and Fruit Bowl, 1924

My Son at 7 Years Old, 1925

Portrait of Maurice Utrillo, 1925

Bouquet of Flowers, 1928

Still Life with Basket of Apples Vase of Flowers, 1928

Young Girl in Front of a Window, 1930

Suzanne Valadon, Autoportrait, huile sur carton marouflé sur bois

Bouquet de roses 1936

Suzanne Valadon, Young Girl Bathing, oil on canvas

Portraits of Valadon[]

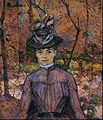

Profile portrait of Suzanne Valadon, by Renoir, 1885

The Hangover (Suzanne Valadon), by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, c. 1888

Portrait of Valadon painted by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

Illustrations[]

- Jean Cocteau, Bertrand Guégan (1892-1943); L'almanach de Cocagne pour l'an 1920-1922, Dédié aux vrais Gourmands Et aux Francs Buveurs[67]

See also[]

- Musée de Montmartre, established in the building in which Valadon had an apartment and studio.

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Marchesseau 1996, p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Warnod 1981, p. 40.

- ^ Adler, Laura (2019). The Trouble with Women Artists: Reframing the History of Art. Paris: Flammarion. p. 51. ISBN 978-2-08-020370-0.

- ^ Warnod 1981, p. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Giraudon 2003.

- ^ "Suzanne Valadon". National Museum of Women in the Arts. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Rose 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Marchesseau 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Drees, Della. "Valadon and her studio in Montmartre". Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ Gimferrer, Pere (1990). Toulouse Lautrec.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marchesseau 1996, p. 15.

- ^ Iskin, Ruth (2004). "The Nude in French Art and Culture". CAA Reviews.

- ^ Smee, Sebastian. "At MFA, dancing the night away in the arms of Renoir". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ "Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jacqui Palumbo. "This rebellious female painter of bold nude portraits has been overlooked for a century". CNN. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Burns 1993, pp. 25–46.

- ^ Betterton, Rosemary (Spring 1985). "How Do Women Look? The Female Nude in the Work of Suzanne Valadon". Feminist Review. 19: 3–24 [4]. doi:10.1057/fr.1985.2. S2CID 144064933.

- ^ Warnod 1981, pp. 48, 57.

- ^ Rose 1999, p. 97.

- ^ "Suzanne Valadon". Brooklyn Museum of Art. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Gaze, Delia (1997). Dictionary of Women Artists Volume 2 Artists, J-Z. Library of the Minneapolis Institute of Art: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. pp. 1384. ISBN 1-884964-21-4.

- ^ Warnod 1981, p. 51.

- ^ Warnod 1981, p. 55.

- ^ Marchesseau 1996, p. 17.

- ^ Marchesseau 1996, pp. 18-19.

- ^ Hewitt 2018, p. 388.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mathews 1991.

- ^ Dolan, Threse (2001). "Passionate Discontent: Creativity, Gender and French Symbolist Art". CAA Reviews. doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.2001.83.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marchesseau 1996, p. 16.

- ^ Marchesseau 1996, pp. 9, 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gaze, Delia (1997). Dictionary of Women Artists, Volume 2 (Artists, J-Z). Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. OCLC 873790995.

- ^ Mathews 1991, p. 418.

- ^ Mathews 1991, pp. 416, 419, 423.

- ^ "Suzanne Valadon". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Warnod 1981, p. 48.

- ^ "Suzanne Valadon". Akademiska Föreningen, Lund University. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ Marchesseau 1996, pp. 17-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jimenez, Jill Berk (2001). Dictionary of Artist's Models. London: Routledge. p. 529.

- ^ Emily (11 September 2013). "Inspired by Art Herstory: Suzanne Valadon's "The Blue Room" (1923)". The Closet Feminist. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Bonazzoli, Francesca, and Michele Robecchi (2020), Portraits Unmasked: The Story Behind the Painting. London, Prestel, pp. 84-87. ISBN 978-3-79-138620-1

- ^ "Suzanne Valadon: An Artist on View Webinar | Washington DC". washington.org. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "The Barnes Foundation". Barnes Foundation. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "La Mère et l'enfant à toilette (Mother and Child at Bath) | Albright-Knox". www.albrightknox.org. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "print | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "CMOA Collection". collection.cmoa.org.

- ^ "Portrait of Utrillo in profile (Portrait d'Utrillo de Profil) - DMA Collection Online". www.dma.org. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "The Bath". www.dia.org. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Toilette de deux enfant dans le jardin - Suzanne Valadon". FAMSF Search the Collections. 8 May 2015.

- ^ Harvard. "From the Harvard Art Museums' collections The Hangover (Suzanne Valadon)". harvardartmuseums.org. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "untitled (Man with Hat)". Indianapolis Museum of Art Online Collection. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "results for 'Suzanne Valadon'". New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "Women, Suzanne Valadon ^ Minneapolis Institute of Art". collections.artsmia.org.

- ^ "Oeuvre : Précisions - Nu au châle bleu | Musée Unterlinden". Musée Unterlinden - WebMuseo (in French). Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Marie Coca et sa fille | Musée des Beaux Arts". www.mba-lyon.fr.

- ^ "Works by Suzanne Valadon in the MFAH Collections". The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

- ^ "Suzanne Valadon". The Museum of Modern Art.

- ^ "Suzanne Valadon | National Museum of Women in the Arts". nmwa.org.

- ^ "Untitled (Still Life)". art.nelson-atkins.org. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Michalska, Magda (23 September 2016). "Suzanne Valadon: The Mistress Of Montmartre". DailyArtMagazine.com - Art History Stories.

- ^ "Digital Collection | The Rose Art Museum | Brandeis University - Young Girl (Jeune Fille)". rosecollection.brandeis.edu. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Works | Suzanne Valadon | People | Smart Museum of Art | The University of Chicago". smartcollection.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Exchange: Bather Seated". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Warnod 1981, p. 88.

- ^ https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9001153/suzanne-valadon

- ^ Koren, Elaine Todd (2001). Suzanne: of Love and Art. Maverick Books. ISBN 0967235529.

- ^ The Razor's Edge by W. S. Maugham

- ^ Notice WorldCat; sudoc; BnF. Engraved on wood and unpublished drawings of: Matisse, J. Marchand, R. Dufy, Sonia Lewitska, de Segonzac, Jean Émile Laboureur, Friesz, Marquet, Pierre Laprade, Signac, Louis Latapie, Suzanne Valadon, Henriette Tirman and others.'

References[]

- Burns, Janet M. C (1993). "Looking as Women: The Paintings of Suzanne Valadon, Paula Modersohn-Becker and Frida Kahlo". Atlantis. 18 (1&2): 25–46. ISSN 0702-7818. OCLC 936739756.

- Giraudon, Colette (2003). "Valadon, Suzanne". Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t087579.

- Hewitt, Catherine (2018). Renoir's dancer : the secret life of Suzanne Valadon. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781250157645, 9781785782749 OCLC 1006391440, 1026408741. Lay summary – She Was a Model for Impressionist Masters. Then She Became One Herself. — NY Times (29 May 2018).

- Marchesseau, Daniel (1996). Suzanne Valadon : [exposition] 26 janvier-27 mai 1996. Martigny, Switzerland: Fondation Pierre Gianadda. ISBN 9782884430364. OCLC 34256669.

- Mathews, Patricia (1991). "Returning the Gaze: Diverse Representations of the Nude in the Art of Suzanne Valadon". Art Bulletin. 73 (3): 415–30. doi:10.2307/3045814. JSTOR 3045814.

- Rose, June (1999) [1998]. Suzanne Valadon: The Mistress of Montmartre. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312199210. OCLC 1036881995 – via Internet Archive.

- Warnod, Jeanine (1981). Suzanne Valadon. Translated by Jennings, Shirley. New York. ISBN 9780517544990. OCLC 7573059.

Further reading[]

- Birnbaum, Paula (2011). Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities. Farnham, Surrey, UK, England Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 9781351536714. OCLC 994145627.

- Storm, John (1958). The Valadon Drama: The Life Of Suzanne Valadon. New York: Dutton. hdl:https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000836363. OCLC 988270982 – via Internet Archive and HathiTrust. Reprinted in 2018 and 2017: ISBN 9781388181154, 9781773230412

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suzanne Valadon. |

- Suzanne Valadon

- French women painters

- Modern painters

- French artists' models

- 1865 births

- 1938 deaths

- 19th-century French painters

- 20th-century French painters

- 20th-century French women artists

- 19th-century French women artists

- Members of the Ligue de la patrie française

- People of Montmartre

- French circus performers