Taksin's reunification of Siam

| Thonburi reunification of Siam | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

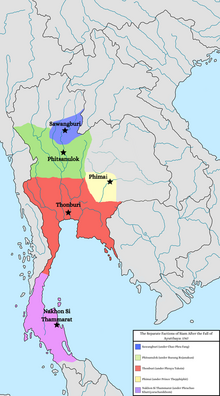

Map of the five Siamese states (including their capital cities) that emerged following the dissolution of the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1767 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

State of Phimai State of Phitsanulok State of Sawangburi State of Nakhon Si Thammarat Principality of Banteay Mas (Hà Tiên) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

† (MIA) (POW) Mạc Thiên Tứ | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Following the Sack of Ayutthaya and the collapse of the Ayutthaya Kingdom during the Burmese–Siamese War (1765–1767), a power vacuum left Siam divided into 5 separate states—Phimai, Phitsanulok, Sawangburi, Nakhon Si Thammarat, and Thonburi. The state of Thonburi, led by Taksin, would ultimately prevail, subjugating its rivals to successfully reunify Siam under the Thonburi Kingdom by 1770/71.[3][4][a]

Five separate states[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (December 2021) |

After the sacking of Ayutthaya the country had fallen apart, due to the disappearance of central authority. In its absence, five major rival Siamese states occupied the vacuum. Banditry was rampant.[citation needed]

The State of Phimai[]

Prince (เทพพิพิธ) [th], King Borommakot's son who returned to Siam from exile in Sri Lanka during the final siege of Ayutthaya , unsuccessfully performing a diversionary action against the Burmese in 1766, had set himself up as the ruler of Phimai holding sway over land in the Isan region (then known as Khorat), governing from the city of Phimai, which spanned a huge chunk of the Isan region. Out of the five, only Thepphitphit would claim legitimacy to the monarchs of Ayutthaya.[5][6]

The State of Phitsanulok[]

(เรือง โรจนกุล) [th], the governor of Phitsanulok, had proclaimed himself independent, with the territory under his control extending from Tak to Nakhon Sawan.

The State of Sawangburi[]

(เจ้าพระฝาง) [th], an influential monk, established his own state with the capital set in the town of Sawangburi, 10 km east of Uttaradit city. His territory extended from Uttaradit to Nan.

The State of Nakhon Si Thammarat[]

(พระเจ้าขัตติยราชนิคม) [th], the governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat, declared his independence and raised himself to princely rank.[7] His territory covered most of what is now southern Thailand.

The State of Thonburi[]

Phraya Taksin, the governor of Tak, of Teochew and possibly of Thai ancestry, established his new capital at Thonburi, after initially basing his operations out of Chanthaburi.[8] His following was a varied assortment of Chinese merchants, adventurers, and minor nobles,[9] and would go on to successfully reunify Siam in the next few years.

Taksin's campaigns of reunification[]

Prelude[]

On 3 January 1767, 3 months before the fall of Ayutthaya,[10] Taksin made his way out of the city at the head of 500 followers to Rayong, on the east coast of the Gulf of Thailand.[11] This action was never adequately explained, as the royal compound and Ayutthaya proper was on an island. How Taksin and his followers fought their way out of the Burmese encirclement remains a mystery. He travelled first to Chonburi, a town on the Gulf of Thailand's eastern coast, and then to Rayong, where he raised a small army and his supporters began to address him as Prince Tak.[12] He planned to attack and capture Chanthaburi, according to a popular version of oral history, he said, "We are going to attack Chanthaburi tonight. Destroy all the food and utensils we have, for we will have our food in Chanthaburi tomorrow morning."[13]

On 7 April 1767, Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese. After the destruction of Ayutthaya and the death of the Thai king, the country was split into six parts, with Taksin controlling the east coast. Together with Thongduang, now Chao Phraya Chakri, he eventually managed to drive back the Burmese, defeat his rivals and reunify the country.[14]

With his soldiers he moved to Chanthaburi, and being rebuffed by the governor of the town, he made a surprise night attack and captured Chanthaburi on 15 June 1767, only two months after the sack of Ayutthaya.[15] His army was rapidly increasing in numbers, as men of Chanthaburi and Trat, which had not been plundered and depopulated by the Burmese,[16] naturally constituted a suitable base for him to make preparations for the liberation of his motherland.[17]

Having thoroughly looted Ayutthaya, the Burmese did not seem to show serious interest in holding the capital of Siam, since they left around 3,000 troops under General Suki to control the shattered city. They turned their attention to the north of their own country, which was soon threatened with four massive Chinese invasion.

Thonburi[]

In October 1767, Taksin captured the town of Thonburi, then a small port just 20 km to the Gulf of Thailand, across the Chao Phraya River from present-day Bangkok. Due to its close proximity to the ocean, Taksin established his new capital at the port town.[18]

In December 1767, Taksin underwent a coronation of sorts, declared himself king, and held a symbolic funeral for the deceased King Ekkathat.[19][20]

Recapture of Ayutthaya[]

On 6 November 1767, having amassed 5,000 troops, Taksin sailed up the Chao Phraya River and seized Thonburi an area opposite of present day Bangkok. He executed the puppet Thai governor, Thong-in, whom the Burmese had placed in charge.[21] He followed up his victory quickly by attacking the main Burmese camp in the near Ayutthaya.[22] The Burmese were defeated and Taksin won back Ayutthaya from the enemy within seven months of its destruction.[17]

Bang Kung campaign[]

Hsinbyushin of Burma had never abandoned his plan to force Siam to its knees, and as soon as he had been informed of the foundation of Thonburi as Taksin's capital, he commanded the Governor of Tavoy, Maengki Manya (Thai: แมงกี้มารหญ้า), to subjugate him in 1767. The Burmese Army numbering 2,000 men advanced to the district of Bang Kung in the province of Samut Songkram to the west of the new capital, but was routed by the Thai king in the in 1767, which is also the site of Wat Bang Kung.[23][24] When more Chinese troops invaded Burma, Hsinbyushin was forced to recall most of his troops back to resist the Chinese.

Invasion of Phitsanulok[]

In 1768, Taksin sent an army to attack Phitsanulok. Taksin was injured during the campaign and had to retreat, however, it was a cadmean victory for the State of Phitsanulok as it was weakened to the point that it was subjugated by the State of Sawangburi. died on the same year. However, the cause of his death remains unknown. Some scholars speculate that his death was from tuberculosis.

Invasion of Phimai[]

In the same year, Taksin sent two commanders, Thongduang (later Rama I) and Bunma, both brothers, to attack the State of Phimai. The invasion was a success and forced Thepphiphit, the ruler of Phimai to flee to Vientiane. Thepphiphit was later captured and then executed.

Invasion of Nakhon Si Thammarat[]

In 1769, Thongduang, now Phraya Chakri, attacked Nakhon Si Thammarat, but got bogged down at Chaiya. Taksin sent his army to help capturing Nakhon Si Thammarat and finally won. The governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat was taken prisoner by the governor of Pattani and delivered to Taksin. The governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat was pardoned by Taksin and given a residence at the capital at Thonburi.[25]

Invasion of Sawangburi[]

In 1770, , the ruler of the State of Sawangburi invaded the State of Thonburi. The Sawangburi forces reached as far as Chai Nat. Taksin saw the invasion as a threat to his rule. He decided to deal with this matter and ordered an invasion of the State of Sawangburi. Taksin was accompanied by Phraya Phichai, who led the west army and Bunma who led the east army. The Thonburi forces easily took Phitsanulok and captured Sawangburi in the next 3 days. Thonburi had finally reunified Siam as one kingdom.[26] 's fate is unknown as he disappeared following the capture of Sawangburi.

In 1770, the Burmese army attacked the city of Sawankhalok, but was repulsed.

Invasion of Banteay Mas[]

In 1771, following repeated failed attempts made by the Cantonese merchant ruler of Banteay Mas (Hà Tiên), Mạc Thiên Tứ, to undermine Taksin in a bid to expand his own territory into Siam and Cambodia, Taksin launched a retaliatory land and naval assault on Hà Tiên, which resulted in Mo Thien Tu's flight, thereby ending the last serious threat to Taksin's early rule.[27] Mạc Thiên Tứ would later return and retake Hà Tiên, with Vietnamese assistance, two years later.

Aftermath[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (December 2021) |

In order to prevent another situation like the one which ended the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1765-67, Taksin launched several expeditions to vassalize the Northern Thai state of Lan Na, then under Burmese vassalage for around two centuries.[28] In 1770, Taksin started his first expedition to capture Chiang Mai, but was pushed back.[citation needed] In 1771, the Burmese governor of Chiang Mai launched an attack on the city of Phichai, beginning a series of conflicts over Siam's northern cities (Sukhothai[clarification needed], Phitsanulok).

In 1772, the Burmese attacked Phichai, but were repelled, followed by another failed invasion on Phichai in 1773.

In 1774, Taksin successfully took the city of Chiang Mai, thereby ending 200 years of Burmese rule over Lan Na. In response, Hshinbyushin, after finally making peace with the Qing in 1774, sent out a military expedition force of 5,000 men to attack Taksin, who were ultimately defeated by Siamese forces at the Battle of Bangkaeo in Ratchaburi. Taksin spared the lives of the captured Burmese soldiers to boost Siamese morale.

In response, in October 1775, Hshinbyushin sent out a major military expedition of 35,000 men to attack Siam, led by Maha Thiha Thura. It was the largest invasion force the Thonburi Kingdom ever faced and the largest Burmese invasion force into Siam since the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767.

See also[]

- Taksin the Great

- Thonburi Kingdom

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (p. 307). (Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (p. 307). (Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (p. 262). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Wood, p. 254

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (p. 263). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (p. 25). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World (p. 262). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ John Bowman (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 514. ISBN 0-231-11004-9.

- ^ Eoseewong, p. 126

- ^ "King Taksin's shrine". Royal Thai Navy. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Eoseewong, p. 98

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, p. 385

- ^ "Art&Culture" (in Thai). Crma.ac.th. Archived from the original on June 22, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ a b W.A.R.Wood, p. 253

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (p. 263). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "History of Ayutthaya - Temples & Ruins - Wihan Phra Mongkhon Bophit". www.ayutthaya-history.com. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 401–402

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 403

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 411–414

- ^ นิธิ เอียวศรีวงศ์. หน้า 148.

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 423–424

- ^ Wood, p. 259.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (p. 263-264). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. p. 124. ISBN 974957544X. "The Burma force had been able to strangle Ayutthaya by seizing the north and the south. Thonburi could not be safe unless these territories at least were denied the enemy or preferably within the Siam orbit."

Sources[]

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4 (Hardback), ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2 (Paperback).

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2014). A History of Thailand. 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107420212.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Damrong Rajanubhab, Prince (1920). The Thais Fight the Burmese (in Thai). Matichon. ISBN 978-974-02-0177-9.

- Wood, W.A.R. (1924). A History of Siam. London: T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd.

- Thonburi Kingdom

- Military history of Thailand

- Wars involving the Thonburi Kingdom

- Conflicts in 1767

- Conflicts in 1768

- Conflicts in 1769

- Conflicts in 1770

- Conflicts in 1771

- 1760s in Asia

- 1770s in Asia

- 1700s in Asia

- 1767 in Asia

- 1768 in Asia

- 1769 in Asia

- 1770 in Asia

- 1771 in Asia

- 18th century in Siam

- 1760s in Thailand

- 1770s in Thailand

- 1767 in Thailand

- 1768 in Thailand

- 1769 in Thailand

- 1770 in Thailand

- 1771 in Thailand