Thonburi Kingdom

Thonburi Kingdom อาณาจักรธนบุรี Anachak Thonburi | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1767–1782 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Trade flag | |||||||||||||||||||||

The sphere of influence of the Thonburi Kingdom following the vassalization of the Lao kingdoms (Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Champasak) in 1778 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Thonburi | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Thai (official) Northern Thai Southern Thai Lao Khmer Shan Malay Various Chinese languages[1] Various minor Kra–Dai languages | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1767–1782 | Taksin the Great | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 28 December 1767 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1767–1770/71 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Vassalizaton of Lan Na | 1774 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1775–1776 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Vassalization of Lao kingdoms | 1778 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Dissolution | 6 April 1782 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pod Duang | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

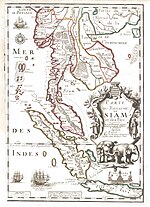

The Thonburi Kingdom (Thai: ธนบุรี) was a major Siamese kingdom which existed in Southeast Asia from 1767 to 1782, centered around the city of Thonburi, in Siam or present-day Thailand. The kingdom was founded by Taksin the Great, who reunited Siam following the collapse of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, which saw the country separate into five warring regional states. The Thonburi Kingdom oversaw the rapid reunification and reestablishment of Siam as a preeminient military power within mainland Southeast Asia, overseeing the country's expansion to its greatest territorial extent up to that point in its history, incorporating Lan Na, the Laotian kingdoms (Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Champasak), the northern Malay states, and Cambodia under the Siamese sphere of influence.[2]

The Thonburi Kingdom saw the consolidation and continued growth of Chinese trade from Qing China, a continuation from the late Ayutthaya period (1688-1767), and the increased influence of the Chinese community in Siam, with Taksin and later monarchs sharing close connections and close family ties with the Sino-Siamese community.

The Thonburi Kingdom lasted for only 14 years, ending in 1782 when Taksin was deposed by a major Thonburi military commander, Chao Phraya Chakri, who subsequently founded the Rattanakosin Kingdom, the fourth and present ruling kingdom of Thailand.

History[]

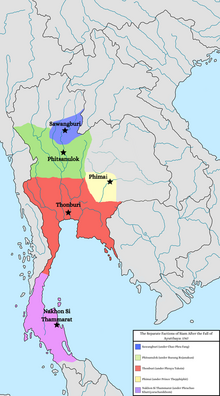

Reestablishment of Siamese authority[]

In 1767, after dominating Southeast Asia for 400 years, the Ayutthaya Kingdom was destroyed. The royal palace and the city were burnt to the ground. The territory was nominally occupied by the Burmese army, while local leaders declared themselves as independent overlords, including the lords of Sakwangburi, Phimai, Chanthaburi, and Nakhon Si Thammarat. Chao Tak, a nobleman of Chinese descent and a capable military leader, proceeded to make himself a lord by right of conquest, beginning with the legendary sack of Chanthaburi. Based at Chanthaburi, Chao Tak raised troops and resources, and sent a fleet up the Chao Phraya to take the fort of Thonburi. In the same year, Chao Tak was able to retake Ayutthaya from the Burmese only seven months after the fall of the city, on 6 November 1767, the symbolic date of liberation against Burmese occupation, still celebrated in Thailand in present-day.[3]

Upon Siamese independence, Hsinbyushin of Burma ordered the ruler of Tavoy to invade Siam. The Burmese armies arrived through Sai Yok and laid siege on the Bang Kung camp – the camp for Taksin's Chinese troops – in modern Samut Songkhram Province. Taksin hurriedly sent one of his generals Boonma to command the fleet to Bang Kung to relieve the siege. Siamese armies encircled the Burmese siege and defeated them.

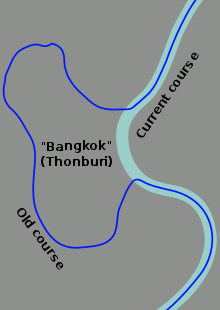

Ayutthaya, the center of Siamese authority for hundreds of years, was so devastated that it could not be used as a government center. Tak founded the new city of Thonburi Sri Mahasamut on the west bank of Chao Phraya River. The construction took place for about a year while Tak crowned himself King of Siam on 28 December 1767, at Thonburi Palace, as King Sanphet but he was known to people as King Taksin – a combination of his title and personal name.[citation needed] Taksin crowned himself as a King of Ayutthaya to signify the continuation to ancient glories.[4]

Reunification and expansion[]

Five States[]

After the sacking of Ayutthaya the country had fallen apart, due to the disappearance of central authority. 5 major rival states had occupied the vacuum.

Phimai[]

Prince Thepphiphit (เทพพิพิธ) [th], Borommakot's son, who had been unsuccessful in a diversionary action against the Burmese in 1766, had set himself up as the ruler of Phimai holding sway over land in the Isan region, governing from the city of Phimai, which spanned a huge chunk of the Isan region.

Phitsanulok[]

The Governor of Phitsanulok, whose first name was Rueang (เรือง) [th], had proclaimed himself independent, with the territory under his control extending from Tak to Nakhon Sawan.

Sawangburi[]

Chao Phra Fang (เจ้าพระฝาง) [th], an influential monk, established his own state with the capital set in the town of Sawangburi, 10 km east of Uttaradit city. His territory extended from Uttaradit to Nan.

Nakhon Si Thammarat[]

The governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat (เจ้าพระยานครศรีธรรมราช) [th], declared his independence and raised himself to princely rank.[5] His territory covered most of what is now southern Thailand.

Thonburi[]

Having firmly established his power at Thonburi, Taksin set out reunify the old kingdom by crushing his regional rivals. After being repulsed by the Governor of Phitsanulok,[6] he concentrated on the defeat of the weakest one first. Teppipit was quelled and executed in 1768.[7] Chao Narasuriyawongse, one of Taksin's nephews, replaced him as governor. Taksin led an expedition against him and took Phimai. The prince disappeared and could not be found again.[8]

Unification of the Five States[]

In 1768, Taksin attacked Phitsanulok. Taksin was injured during the campaign and had to retreat. Phitsanulok was weakened by the invasion and was in turn subjugated by Sawangburi. In the same year, Taksin sent two brothers, Thong Duang and Bunma, members of a powerful Mon noble family, to attack Phimai. Thepphiphit fled to Vientiane but was captured and then executed.

In 1769, Phraya Chakri (later Rama I), Taksin's servant, attacked Nakhon Si Thammarat, but got bogged down at Chaiya. Taksin sent his army to help capturing Nakhon Si Thammarat and finally won. In dealing with the Prince of Nakhon Si Thammarat, who was taken prisoner by the loyal governor of Pattani,[9] the ping not only pardoned him but also favoured him with a residence at Thonburi.

In 1770, Chao Phra Fang invaded Thonburi and reached Chai Nat. Taksin saw the invasion as a threat to his rule, this he decided to invade Sawangburi. Taksin was accompanied by Phraya Pichai, who led the west army and Bunma who led the east army. The Thonburi forces easily took Phitsanulok and captured Sawangburi in the next 3 days. Thonburi had finally reunified Siam as one kingdom.[10]

Taksin stayed at Phitsanulok to oversee the census and levy of northern population. He appointed Boonma to Chao Phraya Surasi as the governor of Phitsanulok and all northern cities and Phraya Abhay Ronnarit to Chao Phraya Chakri the chancellor.

In 1771, Taksin would eliminate the last threat to his rule over Siam by conquering Hà Tiên (Banteay Mas), whose Cantonese leader was attempting to undermine Taksin during the civil war in order to expand his own domain.[11]

Wars with Burma[]

Taksin had consolidated the old Siamese kingdom with a new base at Thonburi. However, the Burmese were still ready to wage massive wars to bring the Siamese down again. From their base at Chiang Mai, they invaded Sawankhalok in 1770 but the Siamese were able to repel. Taksin realized the importance of Lanna as the base of resources for the Burmese to attack Siam's northern territories. If Lanna was brought under Siamese control then the Burmese threats would be eradicated.

At the time Lanna, centered on Chiang Mai, was ruled by a Burmese general Paw Myunguaun. He was the general who led the invasion of Sawankhalok in 1770 but was countered by Chao Phraya Surasi’s armies from Phitsanulok. In the same year, the Siamese pioneered a little invasion of Chiang Mai and failed to gain any fruitful results.

In 1772, Paw Thupla, another Burmese general who had been in wars in Laos, headed west and attack Phichai and Uttaradit. The armies of Phitsanulok once again repelled the Burmese invasions. They came again in 1773 and this time Phraya Phichai made his legendary sword break.

Wars over Lan Na[]

In 1774, Taksin ordered Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi to invade Chiang Mai. After nearly 200 years of Burmese rule, Lanna passed to the Siamese hands. The two Chao Phrayas were able to take Chiang Mai with the help of local insurgents against Burma and Taksin appointed them the local rulers: Phraya Chabaan as Phraya Vichianprakarn the Lord of Chiangmai, Phraya Kawila as the Lord of Lampang, and Phraya Vaiwongsa as Lord of Lamphun. All the lordships paid tribute to Thonburi. Paw Myunguaun and the Burmese authority retreated to Chiang Saen.

During Taksin’s northern campaigns, the Burmese armies took the opportunity to invade Thonburi through Ta Din Daeng. The Burmese encamped at Bangkaeo but were surrounded by the Siamese armies commanded by Taksin in the Battle of Bangkaeo. For more than a month the Burmese had been locked in the siege and thousand of them died.[12] Another thousand became captives to the Siamese.

In 1775, there came the largest invasion of the Burmese led by Maha Thiha Thura. Instead of dividing the forces invading through various ways, Maha Thiha Thura amassed the troop of 30,000 as a whole directly towards Phitsanulok whose inhabitants were only 10,000 in number. Paw Thupla and Paw Myunguaun from Chiang Saen attempted to retake Chiang Mai but were halted by the two Chao Phrayas, who after Chiang Mai hurried back to Phitsanulok to defend the city. The engagements occurred near Phitsanulok.

Maha Thiha Thura directed the troops at Phitsanulok so immensely that the Siamese were about to fall. He cut down the supply lines and attacked the royal army. The two Chao Phrayas decided to abandon Phitsanulok. The Burmese entered the city with victory but due to the death of Hsinbyushin the Burmese king the same year. They had to retreat.

After the death of the Burmese king Hsinbyushin the Burmese were plunged in their own dynastic struggles. In 1776, the new monarch Singu Min sent Maha Thiha Thura to invade Lan Na again with such a huge army that Lord Vichianprakarn of Chiang Mai had to abandon the city. Chao Phraya Surasi and Lord Kawila of Lampang retook Chiang Mai from the Burmese but decided to left the city abandoned as there was no population to fill the city. No further Burmese invasions came as Singu staged his dynastic purges on the princes and Maha Thiha Thura himself.

Wars with Cambodia and Laos[]

Campaigns in Cambodia[]

Prince Ang Non the Uparaja of Cambodia fled to Thonburi in 1769 after his conflicts with King Narairaja [id] for Siamese supports. Taksin then took this opportunity to request tributary from Cambodia, which Narairaja refused. Taksin sent Phraya Abhay Ronnarit and Phraya Anuchit Racha to subjugate Cambodia, taking Siem Reap and Battambang. But Taksin's absence from the capital (in wars with Nakhon Si Thammarat) shook the political stability and the two generals decided to retreat to Thonburi.

Later in 1771, Taksin decided to finish off the Cambodian campaign by assigning Chao Phraya Chakri command of land forces with Prince Ang Non and Taksin himself went by sea. The Siamese took various Cambodian cities and drove Narairaja out of the throne. Ang Non was installed as Reamraja and Narairaja became the Uparaja with the Cambodian court paying tribute to Thonburi.

Campaigns in Laos[]

In 1776, a governor of Nangrong (modern Nakhon Nayok) had a row with the governor of Nakhon Ratchasima, the head city of the region. The governor then sought supports from King Sayakumane of Champasak. This became a casus bellum for Taksin to send Chao Phraya Chakri to conquer Champasak. King Sayakumane fled but was captured and detained in Thonburi for two years until he was sent to rule his kingdom again in 1780 paying tribute to Thonburi. The Champasak campaign earned Chakri the title Somdet Chao Phraya Maha Kasatseuk. Taksin invented the title Somdet Chao Phraya for a mandarin with equal honor as a royalty.

In 1778, a Laotian mandarin named Phra Wo sought Siamese supports against King Bunsan of Vientiane but was killed by the Laotian king. Taksin then dispatched the troops in 1779 led by the two famous brothers commanders, Phraya Chakri and his brother, Phraya Surasi to subjugate Vientiane. At the same time King Suriyavong of Luang Prabang submitted himself to Thonburi and joined the invasion of Vientiane. King Bunsan fled and hid in the forests but later gave up himself to the Siamese. The Vientiane royal family was deported to Thonburi as hostages. Thonburi forces took two valuable Buddha images, the symbolic icons of Vientiane – the Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang to Thonburi. Then all of the three Laotian kingdoms became Siamese tributaries and remained under Siamese rule for another hundred years.

Political and economic troubles, downfall, establishment of Rattanakosin[]

Despite Taksin's successes, by 1779, Taksin was showing signs of mental instability. He was recorded in the Rattanahosin's gazettes and missionaries's accounts as becoming maniacal, insulting senior Buddhist monks, proclaiming himself to be a sotapanna or divine figure. Foreign missionaries were also purged from times to times. His officials, mainly ethnic Chinese, were divided into factions, one of which still supported him but the other did not. The economy was also in turmoil, famine ravaged the land, corruption and abuses of office were rampant, the monarch attempted to restore order by harsh punishments leading to the execution of large numbers of officials and merchants, mostly ethnic Chinese which in turn led to growing discontent among officials.[citation needed] Siamese nobles were alienated by Taksin's unorthodox rule, such as the lack of recreating a "proper capital" at Thonburi, his personal style of leadership, as well as by his religious unorthodoxy.[13]

In 1782 Taksin sent a 20,000 man army to Cambodia, led by generals Phraya Chakri and Bunma, to install a pro-Siamese monarch upon the Cambodian throne following the death of the Cambodian monarch. While the army was en route to Cambodia, Taksin was overthrown in a rebellion that successfully seized the Siamese capital, which, depending on the sources, captured Taksin or allowed Taksin to peacefully step down from the throne and become a monk. Phraya Chakri, upon receiving news of the rebellion while on campaign, hurriedly marched his army back to Thonburi. The story behind Phraya Chakri's seizure of the Siamese throne is disputed: according to Wyatt, Phraya Chakri accepted the rebels' offer to give him the throne after Taksin was deposed by the rebels. According to Baker and Phongchaichit, Phraya Chakri, with his strong support from established nobles, staged a bloody coup d'teat upon arriving at the Siamese capital. What is supported by these sources however is that Taksin was executed shortly after Phraya Chakri's seizure of the capital.[14][15][16]

After securing the capital, Phraya Chakri took the throne as King Ramathibodi, posthumously known as Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke, today known as King Rama I, founding the House of Chakri, the present Thai ruling dynasty. After Taksin's death, Rama I moved his capital from Thonburi, across the Chao Phraya River, to the village of Bang-Koh (meaning "place of the island"), where he would construct his new capital. The new capital was established in 1782, called Rattanakosin, today now known as Bangkok.[citation needed]

The city of Thonburi remained an independent town and province until it was merged into Bangkok in 1971.

Government[]

Thonburi government organization was centered around a loose-knit organization of city-states, whose provincial lords were appointed through 'personal ties' to the king, similar to Ayutthaya and, later, Rattanakosin administrations.[17][18] With the exception of Bunma (later Chao Phraya Surisai and later Maha Sura Singhanat), a member of the old Ayutthaya artistocracy who had joined Taksin early on in his campaigns of reunification, and later Bunma's brother, Thongduang (later Chao Phraya Chakri and later King Rama I), high political positions and titles within the Thonburi Kingdom were mainly given to Taksin's early followers, instead of the already established Siamese nobility who survived after the fall of Ayutthaya, many of whom having supported , the governor of Phitsanulok and an Ayutthaya aristocrat, during the Siamese civil war. In the Northern cities, centered around Sukhothai and Phitsanulok, Taksin installed early supporters of his who had distinguished themselves in battle, many of whom were allowed to establish their own local dynasties afterwards, but elsewhere, several noble families had kept their titles and positions within the new kingdom (Nakhon Si Thammarat, Lan Na), (the ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat that Taksin defeated during the civil war was reinstated as its ruler) whose personal connections made them a formidable force within the Thonburi court.[19][20]

The Thonburi period saw the return of 'personal kingship', a style of ruling that was used by Naresuan but was abandoned by Naresuan's successors after his death. Taksin, similar to Naresuan, personally led armies into battle and often revealed himself to the common folk by partaking in public activities and traditional festivities, thereby abandoning the shroud of mysticism as adopted by many Ayutthaya monarchs. Also similar to Naresuan, Taksin was known for being a cruel and authoritarian monarch. Taksin reigned rather plainly, doing little to emphasize his new capital as the spiritual successor to Ayutthaya and adopted an existing wat besides his palace, Wat Jaeng (also spelled Wat Chaeng, later Wat Arun), as the principal temple of his kingdom. Taksin largely emphasized the building of moats and defensive walls in Thonburi, all while only building a modest Chinese-style residence and adding a pavilion to house the Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang images at Wat Jaeng, recently taken in 1778 from the Lao states (Vientiane and Luang Prabang, respectively).[21]

Population[]

Much of the western provinces of Siam were depopulated for several decades until the early 19th century due to the near-constant state of fighting with Burma.[23]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (December 2021) |

Language[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (December 2021) |

Territory[]

With the exception of the western Tenasserim Coast, the Thonburi Kingdom reconquered most of the land previously held under the Ayutthaya Kingdom and expanded Siam to its greatest territorial extent up to that point. During the Thonburi period, Siam acquired the traditional lands of Lan Na from the Burmese after 200 years of Burmese vassalage, which remains a part of Thailand today.

The following provinces included: Thonburi, Ayutthaya, Ang Thong, Singburi, Lopburi, Uthai Thani, Nakhon Sawan, Chachoengsao, Prachinburi, Nakhon Nayok, Chonburi, Rayong, Chanthaburi, Trat, Nakhon Chai Si, Nakhon Pathom, Suphanburi, Ratchaburi, Samut Sakhon, Samut Songkhram, Phetchaburi, Kanchanaburi, and Prachuap Khiri Khan.

Vassal (mandala) states of the Thonburi Kingdom at its height in 1782, to varying degrees of autonomy, included the Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom, the Northern Thai principalities of Chiang Mai, Lampang, Nan, Lamphun, and Phrae, and the Lao Kingdoms of Champasak, Luang Prabang, and Vientiane.

Military[]

Following the Burmese–Siamese War (1775–1776), the military balance of power within the kingdom shifted as Taksin took away troops from his old followers in the Northern Cities, who had performed disappointingly in the previous war, and concentrated these forces to protect the capital at Thonburi, placing more military power within the hands of two powerful brother-generals from the traditional aristocracy, Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi.[24]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (January 2022) |

Economy and society[]

The years of warfare and the Burmese invasions prevented any peasants to engage in agricultural activities. The Siamese war captives who had been taken to Burma following the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 and the general lack of manpower were the source of the problems. Taksin had tried his best to encourage people to come out of forest hidings, of whom had fled into the countryside prior to and during the 1765-67 Burmese invasion, and to promote farming. He promulgated the in 1773, which left a permanent mark on commoners' bodies, preventing them from fleeing or moving. The practice continued well into the Rattanakosin period until the abolition of levy during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). As Taksin was from a Chinese merchant family, he sold both his royal and familial properties and belongings to subsidize production by giving money off to people. This proved to be a temporary relief for such an economic decline. Nevertheless, the Siamese economy after the wars needed time to rehabilitate. Thonburi began forming its society.

Taksin gathered resources through wars with neighboring kingdoms and deals with Chinese merchants. Major groups of people in Thonburi were local Thais, phrai, or 'commoners', Chinese, Laotians, Khmers, and Mons. Some powerful Chinese merchants trading in the new capital were granted officials titles. After the king and his relatives, officials were powerful. They held numbers of phrai, commoners who were recruited as forces. Officials in Thonburi mainly dealt with military as well as 'business' affairs.

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (January 2022) |

Diplomacy[]

Taksin himself also commissioned trade missions to neighbouring and foreign countries to bring Siam back to outside world, the Qing dynasty being at the forefront of these missions. He dispatched several tributary missions to the Qing in 1781 to resume diplomatic and commercial relationships between the two countries which had stretched back, beginning in the Sukhothai period and had expanded significantly during the late Ayutthaya period.[25]

Early on into his rule, Taksin sent a tributary mission to Qing China to require the royal seal, claiming that the throne of Ayutthaya Kingdom had come to an end. However, in the midsts of the Siamese civil war, the Qing Court initially refused to recognize Taksin as a legitimate ruler, citing the presence of then still-powerful claimants to the Siamese throne. Eventually, the Qing Court approved the royal status of Taksin as the new King of Siam.

In 1776, Francis Light of the Kingdom of Great Britain sent 1,400 flintlocks along with other goods as gifts to Taksin. Later, Thonburi ordered some guns from England. Royal letters were exchanged and in 1777, George Stratton, the Viceroy of Madras, sent a gold scabbard decorated with gems to Taksin.[clarification needed]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (January 2022) |

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thonburi Kingdom. |

- King Taksin the Great

- Coronation of the Thai monarch

- List of Kings of Thailand

- Thonburi province

- Thon Buri (district)

References[]

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. p. 122. ISBN 974957544X. "Within a decade or so, a new Siam already had succeeded where Naresuan and his Ayutthaya predecessors had failed in creating a new Siamese empire encompassing Lan Na, much of Lan Sang [sic], as well as Cambodia, and large portions of the Malay Peninsula."

- ^ จรรยา ประชิตโรมรัน. (2548). สมเด็จพระเจ้าตากสินมหาราช. สำนักพิมพ์แห่งจุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย. หน้า 55

- ^ David K. Wyatt. Thailand: A Short History. Yale University Press

- ^ Wood, p. 254

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 414–415

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 418–419

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, p. 430

- ^ Damrong Rajanubhab, pp. 423–424

- ^ Wood, p. 259.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (p. 263-264). Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ "view diary". bloggang.com.[dead link]

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 267-268. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. p. 128. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 267-268. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (p. 26). Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 265. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 265, 267. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. pp. 125–26, 27–28. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (p. 263, 264). Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (Ch. III). Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ "Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, "A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in…". New Books Network.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 266. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- Thonburi Kingdom

- Former countries in Thai history

- Former countries in Burmese history

- Former countries in Malaysian history

- Former monarchies of Southeast Asia

- Former kingdoms

- Indianized kingdoms

- 1760s in Siam

- 1770s in Siam

- 1780s in Siam

- 18th century in Burma

- 18th century in Siam

- States and territories established in 1767

- States and territories established in 1782

- 1767 in Siam

- 1767 establishments by country

- 1767 establishments in Asia

- 1782 disestablishments in Asia

- 1760s establishments in Siam

- 1780s disestablishments in Siam