Taxation in Norway

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

|

Taxation in Norway is levied by the central government, the county municipality (fylkeskommune) and the municipality (kommune). In 2012 the total tax revenue was 42.2% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Many direct and indirect taxes exist. The most important taxes – in terms of revenue – are VAT, income tax in the petroleum sector, employers' social security contributions and tax on "ordinary income" for persons. Most direct taxes are collected by the Norwegian Tax Administration (Skatteetaten) and most indirect taxes are collected by the Norwegian Customs and Excise Authorities (Toll- og avgiftsetaten).

The Norwegian word for tax is skatt, which originates from the Old Norse word skattr.[1] An indirect tax is often referred to as an avgift.

Taxation in the Constitution[]

According to the Norwegian Constitution, the Storting is to be the final authority in matters concerning the finances of the State - expenditures as well as revenues. This follows from Article 75a of the Norwegian Constitution:

- It devolves upon the Storting ... to impose taxes, duties, customs and other public charges, which shall not, however, remain operative beyond 31 December of the succeeding year, unless they are expressly renewed by a new Storting;[2]

Taxes, excise and customs are adopted by the Storting for one year through the annual (plenary) decision on taxes, excises and customs. The Storting must therefore each year decide to what extent it is desirable to amend the tax scheme. There are essentially no other limitations on the Storting's taxation authority under the Constitution § 75 a than those required by the Constitution itself. The prohibition against retroactive laws in the Constitution § 97 is an example of such a restriction.

The Storting determines each year the maximum tax rates applied to the municipal income and wealth tax to the county income tax. Municipalities and county councils shall, in connection with their budget, adopt the tax rates applied to the local income and wealth tax within the maximum rates set by the Storting. In addition, municipalities can levy a property tax.

The Ministry of Finance sets up the government's tax program, which is included in the fiscal budget proposal. The budget is submitted to the Storting as Proposition No. 1 to the Storting.[3]

Tax administration[]

Tax year in Norway starts on 1 January.

In order to implement the tax program decided by the Storting, the Ministry of Finance is supported by two subordinate agencies and bodies.

The Tax Administration (Skatteetaten) ensures that taxes are set and collected in the correct manner. It issues tax cards, collects advance tax and checks the tax-return forms that are required to be submitted each year. The Tax Administration also determines and monitors national insurance contributions, and value-added tax and are responsible for providing professional guidance and instruction to local tax collection offices that collect direct taxes.[4]

The Customs and Excise Authorities (Toll- og avgiftsetaten) ensures that customs and excise duties are correctly levied and paid on time. In addition, they are responsible for preventing the illegal import and export of goods in Norway. The customs and excise authorities set and collect customs duties, value-added tax on imports and special duties.[5]

Tax level[]

In 2009, the total tax revenue was 41.0% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Of the OECD member countries Denmark, Sweden, Belgium, Italy, France, Finland and Austria had a higher tax level than Norway in 2009. The tax level in Norway has fluctuated between 40 and 45% of GDP since the 1970s.[6]

The relatively high tax level is a result of the large Norwegian welfare state. Most of the tax revenue is spent on public services such as health services, the operation of hospitals, education and transportation.[7]

Revenue levels are also influenced by the important role played by oil and gas extraction in the Norwegian economy.

Allocation of tax revenues[]

In 2010, 86% of taxes were paid to the central government, 2% were paid to regional government, while local government received 12% of the total tax revenue.

The main revenue sources for the central government are VAT, tax on income in the petroleum sector, employers' social security contributions and tax on "ordinary income" from individual taxpayers, while the main revenue source for local and regional authorities is tax on "ordinary income" from individual taxpayers.

The table below provides a general overview of the main groups of taxes and shows which parts of the public sector that receive revenue from each main group.

| Central government | Local government | Regional government | In total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual taxpayers | 218.5 | 115.9 | 22.2 | 356.7 |

| Tax on ordinary income | 104.5 | 107.4 | 22.2 | 234.2 |

| Surtax | 19.0 | - | - | 19.0 |

| Employee's and self-employed's social security contributions | 90.2 | - | - | 90.2 |

| Tax on net wealth | 4.8 | 8.5 | - | 13.3 |

| Businesses (whose taxes are payable the year after the income year) | 59.2 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 60.8 |

| Income tax (including power stations) | 58.9 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 60.4 |

| Tax on net wealth | 0.3 | - | - | 0.3 |

| Property tax | - | 6.6 | - | 6.6 |

| Employers' social security contributions | 132.0 | - | - | 132.0 |

| Indirect taxes | 290.7 | - | - | 290.7 |

| VAT | 194.4 | - | - | 194.4 |

| Excise duties and customs duties | 96.3 | - | - | 96.3 |

| Petroleum | 181.4 | - | - | 181.4 |

| Tax on income | 177.6 | - | - | 177.6 |

| Extraction tax | 3.8 | - | - | 3.8 |

| Other direct and indirect taxes | 27.8 | 0.5 | - | 28.4 |

| Social security and pension premiums, other central government and social security accounts | 21.0 | - | - | 21.0 |

| Tax on dividends to foreign shareholders | 1.7 | - | - | 1.7 |

| Inheritance and gift tax | 2.2 | - | - | 2.2 |

| Other taxes | 2.9 | 0.5 | - | 3.4 |

| Total direct and indirect taxes | 909.7 | 124.3 | 22.5 | 1 056.5 |

| Of which direct taxes | 619.0 | 124.3 | 22.5 | 765.8 |

Direct taxes[]

Personal income tax[]

Norway has, like several other Nordic countries, adopted a dual income tax. Under the dual income tax, income from labour and pensions is taxed at progressive rates, while capital income is taxed at a flat rate.[9]

Employee's and self-employed's national insurance contributions[]

National insurance contributions (trygdeavgift) are levied on personal income (personinntekt). Personal income includes wage income and business income due to active efforts, but generally not capital income, and there is no deductions in labor income and limited right to charge a deduction from business income. The tax rate is 5.1% for pension income, 8.2% for wage income and 11.4% for other business income.[8]

No social security contribution is paid for income below the exemption card threshold (frikortgrense). This threshold is NOK 54,650 in 2018.[10] Then, social security contribution is paid at a levelling rate of 25% (of the income above NOK 54,650) until this gives a higher total tax than using the standard tax rate on all personal income. Then the general rates are used.[8]

| Lower threshold for payment of employee's social security contribution | NOK 54,650 |

| Levelling rate | 25.0% |

| Rate | |

| Wage income | 8.2% |

| Income from self-employment in primary sector | 8.2% |

| Income from other self-employment | 11.4% |

| Pension income, etc. | 5.1% |

Tax on ordinary income[]

Ordinary income (alminnelig inntekt), which consists of all taxable income (wages, pensions, business income, taxable share income and other income) minus deductions (losses, debt interest, etc.), is taxed at a flat rate of 23% in 2018. Residents of northern Troms and Finnmark have a lower tax rate, at 19.5%. In 2010, the tax on ordinary income is split in a local tax (kommunale skattøre) of 12.80%, a regional tax (fylkeskommunale skattøre) of 2.65% and a tax to the central government (fellesskatt) of 12.55%.[12]

Deductions[]

The current income tax system has two standard deductions: minimum standard deduction (minstefradrag)[13] and personal allowance (personfradrag).[14]

The minimum standard deduction is set as a proportion of the income with upper and lower limits. For wage income, the rate is 45% and the upper limit is NOK 97,610 in 2018. The lower limit is the so-called special wage income allowance (lønnsfradrag), which is NOK 31,800 in 2018. The minimum standard deduction for pension income is slightly lower than the basic allowance for wage income.

The personal allowance is a standard deduction from ordinary income, meaning that it is given in all income (wages, pensions, capital and business income).

| Personal allowance | |

| All | NOK 54,750 |

| Minimum standard deduction in wage income | |

| Rate | 45.0% |

| Lower limit | NOK 4,000 |

| Upper limit | NOK 97,610 |

| Basic allowance in pension income | |

| Rate | 31.0% |

| Lower limit | NOK 4,000 |

| Upper limit | NOK 83,000 |

| Special wage income allowance | NOK 31,800 |

Ordinary income is a net income concept, meaning that it will be deduction for costs incurred to acquire income. There is therefore a deduction for expenses related to acquisition of income if these are higher than the basic allowance. There is also several other deductions from ordinary income; special allowance for disability, special tax allowance for pensioners, the tax limitation rule for the disabled, seamen's allowance, fishermen's allowance, special allowance for self-employed within agriculture, special allowance for high expenses linked to illness, allowance for payments to individual pension schemes, allowance for travel between home and work, allowance for donations to voluntary organisations, allowance for paid union fees, allowance for home investment savings scheme for people under 34 years, parental allowance for documented expenses for childminding and childcare, etc.[8]

[]

The shareholder model (aksjonærmodellen) implies that dividends exceeding a risk-free return on the investment (the cost base of the shares) are taxed as ordinary income when distributed to personal shareholders. When added to the 28% company taxation, this gives a total maximum marginal tax rate on dividends of 48.16% (0.28+0.72*0.28).[15] The 2014 corporate tax rate is 27% giving a marginal tax rate on dividends of 46.71%.[16]

The part of the dividend that is not exceeding a risk-free return on the investment, is not taxed on the hand of the shareholder, and is thus subject to the 28% company taxation only. If the dividend for one year is less than the calculated risk-free interest, the surplus tax free amount can be carried forward to be offset against dividends distributed a later year, or against any capital gain from the alienation of the same share.[15]

The shielding method for partnerships[]

The shielding method for partnerships (skjermingsmetoden for deltakerlignede selskaper or deltakermodellen) implies that the partners are subject to 28% taxation upon all income irrespective of distribution, supplemented by 28% additional taxation on distributed profits. In order to compensate for the initial 28% taxation, only 72% of the distributed profit will be taxable. Furthermore, only the distributed profit exceeding a risk-free interest on the capital invested in the partnership will be taxable. The maximum marginal tax rate of distributed income will be 48.16 percent (0.28+0.72*0.28).[15]

The shielding method for self-employed individuals[]

The shielding method for self-employed individuals (skjermingsmetoden for enkeltpersonforetak or foretaksmodellen) implies that business profits exceeding a risk-free interest on the capital invested is taxed as personal income (the tax base for social security contributions and surtax).[15]

Bracket tax[]

The personal income bracket tax (trinnskatt) is, as the employee's and self-employed's social security contributions, levied on personal income. In 2018, is levied in four different income brackets:[17]

| Bracket | Threshold (NOK) | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 0 – 174,500 | 0 | |

| Step 1 | 174,500 – 245,650 | 1.9% |

| Step 2 | 245,650 – 617,500 | 4.2% |

| Step 3 | 617,500 – 964,800 | 13.2% |

| Step 4 | 964,800+ | 16.2% |

Employers' social security contribution[]

Employers in both private and public sector is obliged to pay the employer's social security contribution on labour costs. The employers' social security contribution are regionally differentiated, so that the tax rate depends on where the business is located. In 2018, the rates vary from 0% to 14.1%.[18]

When the employers' social security contribution is included, the maximum marginal tax rate on labour costs is 53.2%.[19]

Corporate taxation[]

Corporate taxable profits (ordinary income) are taxed at a flat rate of 23%.[20][failed verification] The tax base is the sum of operating profit/loss, financial revenues and net capital gains minus tax depreciation. In addition, the profit is taxed on the owner's hand through dividend and capital gain taxation.[15]

The exemption method[]

The exemption method (Norwegian: fritaksmetoden) implies that limited companies are exempted from tax on dividends and on capital gains from the alienation of shares, correspondingly the right to deduct losses on shares was abolished. Combined with the proposal of a model for taxation of individual shareholders (the shareholders model), dividends and gains on shares will be taxed on extraction from the company sector, and only to the extent such income exceeds a risk-free rate of return.[21]

Taxation of petroleum activities[]

The taxation of petroleum activities is based on the rules governing ordinary business taxation. There is considerable excess return (resource rent) associated with the extraction of oil and gas. Therefore, a special tax of 51% on income from petroleum extraction has been introduced, in addition to the ordinary income tax of 23%. Consequently, the marginal tax rate on the excess return within the petroleum sector is 78%.[22]

Taxation of power plants[]

The taxation of power plants is based on the rules governing ordinary business taxation. There is considerable excess return (resource rent) associated with the production of hydro power. Therefore, a special tax of 30% on income from hydro power plants has been introduced, in addition to the ordinary income tax of 23%. Consequently, the marginal tax rate on the excess return within the power sector is 58%.[23][24]

Taxation of shipping income[]

Shipping companies shipping income is exempted from income taxation, but they pay a tonnage tax of vessels they own, and in some cases the vessel they hire. The tax is based on vessels' net tonnage (tons). This tonnage tax must be paid regardless of whether the vessel has been in operation or not.[25][26]

Tax on net wealth[]

Wealth tax is levied at both municipal and central government level. The tax base is net wealth less a basic deduction. In 2018, the basic deduction is NOK 1,480,000 (double this for married couples). The value of a personal residence is assessed at about 25% of its market value for tax purposes. Other residences are assessed at 90% of the market value.[27] As a consequence of basic deduction in combination with gentle assessment rules, especially of housing, the wealth tax is of little importance to most tax-paying households. The municipal tax rate is 0.7%, while the national tax rate is 0.15% for 2018. [28]

Inheritance and gift tax[]

The inheritance tax in Norway was abolished in 2014.[29]

Before the abolition the inheritance and gift tax had a zero rate for taxable amounts up to NOK 470,000. From this level, the rates ranged from 6% to 15% depending on the status of the beneficiary and the size of the taxable amount.[8]

| Threshold | |

| Level 1 | NOK 470,000 |

| Level 2 | NOK 800,000 |

| Rates | |

| Children and parents | |

| Level 1 | 6.0% |

| Level 2 | 10.0% |

| Other beneficiaries | |

| Level 1 | 8.0% |

| Level 2 | 15.0% |

Property tax[]

The municipal councils may choose to impose property taxes in accordance with the Property Tax Law. All property owners may be obliged to pay this tax. The tax is calculated as being between 0.2‰ and 0.7‰ of a property's value.[30] In 2009, 299 municipalities had chosen to tax property and 131 municipalities had chosen not to impose property tax.[31]

Indirect taxes[]

Value added tax[]

Value added tax (Norwegian: merverdiavgift) is a tax on consumption that must be paid on domestic sales of goods and services liable for tax in all links in the chain of distribution and on imports. The rates for VAT for 2013 are as follows:

- 25% general rate

- 15% on foodstuffs

- 12% on the supply of passenger transport services and the procurement of such services, on the letting of hotel rooms and holiday homes, and on transport services regarding the ferrying of vehicles as part of the domestic road network. The same rate applies to cultural events, museums, cinema tickets and to the television license.[8]

In principle, all sales of goods and services are liable to VAT. However, some supplies are exempt (without a credit for input tax), which means that such supplies fall entirely outside the scope of the VAT Act. Businesses that only have such supplies cannot register for VAT, and are not entitled to deduct VAT. Financial services, health services, social services and educational services are all outside the scope of the VAT Act.[32]

Some supplies are zero-rated (exempt with a credit for input tax). When a supply is zero-rated, it means that the supply falls within the scope of the VAT Act, but output VAT shall not be calculated as the rate is zero. Newspapers, books and periodicals are zero-rated.[33]

Excise duties[]

Excise duties (Norwegian: særavgifter) are taxes levied on particular goods and services, of foreign or domestic origin. In addition there are excise duties connected to ownership or change of ownership of certain goods and real property. Revenues mostly derive from the former category.

Excise duties can be on purely fiscal grounds, i.e. that they only intend to raise the state income, but excise duties can also be used as an instrument to correct for external effects, such as related to the use of health and environmentally damaging products.

The most important excise duties in Norway, in terms of revenue, are tax on alcoholic beverages, tax on tobacco goods, motor vehicle registration tax, annual tax on motor vehicles, road use tax on petrol, road use tax on diesel, electricity consumption tax, CO2 tax and stamp duty.[8]

Customs duties[]

Customs duties (Norwegian: toll) shall be paid upon importation of goods. The ordinary rate of the Customs Tariffs applies for goods imported from countries with whom Norway has not entered into a free trade agreement (FTA), and for goods imported from a FTA-party, but not satisfying by the conditions for preferential tariff treatment as set out in these agreements. All products originating in the Least Developed Countries are granted duty-free treatment[34]

The customs duties on agricultural products is an important part of the overall support for Norwegian agriculture. Of manufacturing goods only some clothing and textiles are currently subject to customs duties.

History[]

Middle Ages[]

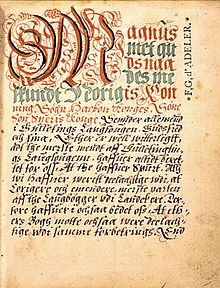

National Archival Services of Norway

Taxation in Norway can be traced back to the petty kingdoms before the unification of Norway. The kings of the petty kingdoms were not permanent residents of one single royal estate, but were moving around in their kingdom, staying for a while at royal estates in each part of it. The peasants in the area where the king stayed, were obliged to provide payment in kind to the king and his entourage. This obligation is called veitsle. This performance of the peasants to their king, has most likely been an important and necessary source of income for the petty kingdoms and made it possible for the king and his entourage to live off the profits from the farming society.[35]: 297 Veitsle was continued when the unified Norwegian kingdom arose. The early national kingdom had in addition other casual tax revenues like finnskatt (and possibly tax revenues from Shetland, Orkney, the Faroes and Hebrides) and trade and travel fees (landaurar).[35]: 294

The second important tax that emerged during the unification was the leidang. This was originally a defensive scheme where all armed men would meet and fight for their king when peace was threatened, but in Norway the leidang evolved to primarily be a naval defence. The agreement between the king and his people must from the beginning have included a crew arrangement and an outfitting and provisioning system. The most important regular, often annual burden for the population, must have been the dietary performance to the crew of the leidang fleet. The provisioning system soon developed into a regular tax, the leidang tax. The leidang was codified in the provincial laws (Gulating law and Frostating law) and later in Magnus Lagabøte's Landslov.[35]: 262–73

It was not just the king who demanded taxes. The church had significant tax revenues in the form of tithe which became law over most of the country in Magnus Erlingson's days (1163-1184).[36]

The Kalmar Union and the union with Denmark[]

In the 1500s, the leidang tax was supplemented by additional taxes imposed when the government needed extra revenue, as in wartimes. From 1600 the additional taxes were imposed more frequently and around 1620 the tax became annual. The leilending (tenant farmer) tax was a property tax where farms were divided into three groups depending on the size of the farms (full farms, half farms, and deserted farms). The tax was from the 1640s dependent on the land rent. In 1665, Norway got its first land register (Norwegian: matrikkel) with a land rent that reflected the value of the production of the farm. The leilending tax was therefore a tax on the expected returns in agriculture.[37]

In the 17th century customs increased in importance as a revenue source and became the governments' main source of income in Norway. Both the rates and the number of commodities tariffs were imposed on increased. Until about 1670 the main objective of the customs duty was to provide government revenue, but customs gradually became a trade policy instrument used to protect domestic production against competition from imported goods.[37]

In the 17th century excises were introduced. The oldest excise duty still existing in Norway is the stamp duty which originates from the regulation regarding det stemplede papiir of 16 December 1676.[38]

In 1762 a new personal tax was introduced, the additional tax (ekstraskatten), a lump sum tax of one riksdaler for each person above 12 years. The tax triggered a storm of indignation, and after a series complains to the king and regular riots, the Stril War, the tax was reduced and finally abolished in 1772.[39]

19th century[]

In 1816, a number of old taxes to the state were merged and replaced by a direct land and township tax (Norwegian: repartisjonsskatt). The tax amount was divided by 4/5 on villages and 1/5 on the cities. The tax was levied on the land register in the villages and mainly on income and economic activity in cities. The tax was very unpopular among farmers, and it was abolished when the farmer's representatives won a majority in the 1836 election. From 1836 to 1892 there existed no direct taxes to the state.[40]

Before 1882, municipal expenditures were covered with several types of taxes. Taxes were paid directly to the various funds that were responsible for financing and operating various types of municipal services. In the cities there were two main taxes: the city tax and the poor tax. The City Tax was originally imposed on real estate and businesses, but during the 19th century it evolved into a property tax. In the countryside there were more funds than in cities. The most important was the poor relief fund and the school fund. The taxes to these funds were determined, respectively by the poor commission and the school commission and were assessed on income, wealth and the value of the property. After the municipal self-government was introduced in 1837, the influence of elected representatives in the commissions and the commissions increased, and the taxes were soon under the control of the municipal council.[40]

In the tax reform of 1882 the system of earmarking the revenue for certain purposes or funds was abolished. Income and wealth tax became mandatory tax bases in addition to the property tax. Income and wealth was estimated discretionary basis by the tax authorities. The gross income was less the costs of acquiring the income was called expected income. It was then given an allowance depending on family responsibilities in order to arrive at taxable income.[41]

There were no state taxes in the period 1836–1892. The state got its revenue from customs and excise duties. These tax bases, however, was too narrow to cover the growth in government expenditure at the end of the 19th century. Therefore, a progressive income and property taxes to the state was introduced in 1892.[42]

20th century[]

The tax reform in 1911 did not lead to significant changes in the tax system. The main change was that the tax return was introduced. Prior to the 1911 tax reform tax authorities had estimated taxable income and property. This system was now replaced by the taxpayers themselves reporting data on income and wealth.[43]

Throughout the 19th century and until World War I, customs were the main source of income for the government. In most of this period customs duties contributed to more than 80% of the government's revenue. Throughout the 20th century, tariffs had less and less financial importance. Excises was also an important source of revenue for the government. In the 19th century alcohol tax and stamp duty were important sources of revenue. Excises became even more important during the World War I when taxes on tobacco and motor vehicles were introduced. A sales tax was introduced in 1935. This was a cumulative tax as originally constituted 1% of the market value of each commercial level. The rate was subsequently increased several times. In 1970, the GST replaced by value added tax (VAT).[44]

1992 tax reform[]

In recent times there have been two major tax reforms in Norway. The first, the tax reform of 1992, was a pervasive and principle based reform, inline with the international trend of broader tax base and lower rates. Corporate taxation was designed so that the taxable profit should correspond to the actual budget surplus. This meant, among other things that different industries, forms of ownership, financing methods and investment were treated equally (neutrality) and that revenues and related expenditures were subject to the same tax rate. In the personal income tax, a clearer distinction between labour income and investment income was introduced (split – a dual income tax system). Ordinary income, income less standard deductions and deductible expenses, was taxes at a flat rate of 28%. On personal income, income from work and pensions, there were in addition levied social security contributions and surtax. To avoid that income that was taxed at the corporate level also were taxed at the individual level (double taxation), the imputation tax credit for dividends and treasury system gains was introduced.

2006 tax reform[]

After the 1992 tax reform the marginal tax rate on labour income was much higher than the marginal tax rate on capital income. For self-employed, it was profitable to convert labour income to capital income (income shifting). In the 2006 tax reform, the income shifting problem was solved by reducing the top marginal tax rate on labour income and introducing a dividend and capital gains tax on return above the normal return of the capital invested (shareholder model). Company shareholders were exempt from dividend and capital gains tax (exemption method), whilst proprietorships and partnerships were taxed at similar principles as the shareholder model.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka" (in Norwegian). Dokumentasjonsprosjektet/EDD. 28 July 2008.

- ^ "The Constitution". Stortinget. 11 September 2008.

- ^ "About the Storting: Budget". Stortinget. 27 May 2008.

- ^ "The Tax Administration (Skatteetaten)". Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "The Customs and Excise Authorities (Toll- og avgiftsetaten/Tollvesenet)". Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "OECD.Stat Extracts Revenue Statistics - Comparative tables". OECD. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ "Selected Topics: Direct and indirect taxes". Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Main features of the Government's tax programme for 2011". Ministry of Finance. 5 October 2010.

- ^ Kleinbard, Edward D. (2010). "An American Dual Income Tax: Nordic Precedents". Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy. Northwestern University School of Law. 5 (1): 41–86. SSRN 1595079.

- ^ "Frikort". Skatteetaten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "National Insurance contributions". Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Prop. 1 LS (2010–2011) Skatter og avgifter 2011, 3.5 Endringer i kommunale og fylkeskommunale skattører og fellesskatt for 2011". Ministry of Finance (in Norwegian). 5 October 2010.

- ^ "Minimum standard deduction". Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Personal Allowance". Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Ministry of Finance. "The corporate tax system and taxation of capital income". Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Regjeringens forslag til skatte- og avgiftsopplegg for 2014" [The Government's proposal for a tax scheme for 2014]. Government.no (in Norwegian). 8 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Bracket tax". Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Employer's national insurance contributions". Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Maximum effective marginal tax rates". Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Taxnorway: Paying tax and value added tax for the company". Norwegian Tax Administration. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Press Release 81/2004 Tax Exemption for Companies' Income from Shares". Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Taxation of petroleum activities". Ministry of Finance. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "Skatteloven §§ 18-1 to 18-8". Government.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Stortingets skattevedtak 2010 § 3-4" (in Norwegian). lovdata.no. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Skatteloven §§ 8-10 til 8-20" (in Norwegian). lovdata.no. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Stortingets skattevedtak 2010 § 5-1" (in Norwegian). lovdata.no. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Fastsettelse av formuesverdi på bolig i skattekortet" (in Norwegian). Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Wealth tax". Skatteetaten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Tabeller og satser - Skatteetaten". www.skatteetaten.no. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Eigedomsskattelova" (in Norwegian). lovdata.no. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Extended use of property tax in municipalities". Statistics Norway. ssb.no. 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Merverdiavgiftsloven §§ 6-21 to 6-33" (in Norwegian). lovdata.no. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Merverdiavgiftsloven §§ 6-1 to 6-20" (in Norwegian). lovdata.no. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Norwegian Customs Tariff: Information". toll.no. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Andersen, Per Sveaas (1977). Samlingen av Norge og kristningen av landet (in Norwegian). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. ISBN 82-00-02412-1.

- ^ Danielsen, Rolf (1991). Grunntrekk i norsk historie (in Norwegian). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. ISBN 82-00-21273-4.[page needed]

- ^ a b Dyrvik, Ståle (1990). Norsk økonomisk historie 1500-1970, Bind 1 1500–1850 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. ISBN 82-00-01921-7.[page needed]

- ^ "NOU 2007: 8 En vurdering av særavgifter, kapittel 3". Government.no (in Norwegian). 22 June 2007.

- ^ Bagge, Sverre; Mykland, Knut (1996). Norge i dansketiden (in Norwegian). Cappelen. ISBN 82-02-12369-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b Gerdrup 1998, p. 11–3.

- ^ Gerdrup 1998, p. 16–7.

- ^ Gerdrup 1998, p. 17.

- ^ Gerdrup 1998, p. 18.

- ^ Gabrielsen 1992.

Bibliography[]

- Gabrielsen, Inger (1992). Det norske skattesystemet 1992 (PDF). Samfunnsøkonomiske Studier (in Norwegian). 79. Statistics Norway. ISBN 82-537-3728-9. ISSN 0801-3845.

- Gerdrup, Karsten R. (1998). Skattesystem og skattestatistikk i historisk perspektiv (PDF). SSB Rapporter (in Norwegian). 98. Statistics Norway. pp. 41–86. ISBN 82-537-4531-1. ISSN 0806-2056.

Further reading[]

"The Norwegian tax system - main features and developments" (PDF). Ministry of Finance. 2012.

"Tax Facts Norway 2012 - A survey of the Norwegian Tax System" (PDF). KPMG Law Advokatfirma DA. 2012.

"International Tax - Norway Highlights 2013" (PDF). Deloitte Global Services Ltd. 2013.

"Taxation and Investment in Norway 2011" (PDF). Deloitte Global Services Ltd. 2011.

External links[]

- Taxation in Norway

- Economy of Norway