Energy in Norway

Norway is a large energy producer, and one of the world's largest exporters of oil. Most of the electricity in the country is produced by hydroelectricity. Norway is one of the leading countries in the electrification of its transport sector, with the largest fleet of electric vehicles per capita in the world (see plug-in electric vehicles in Norway and electric car use by country).

Since the discovery of North Sea oil in Norwegian waters during the late 1960s, exports of oil and gas have become very important elements of the economy of Norway. With North Sea oil production having peaked, disagreements over exploration for oil in the Barents Sea, the prospect of exploration in the Arctic, as well as growing international concern over global warming, energy in Norway is currently receiving close attention.

Overview[]

| Population (million) |

Primary energy (TWh) |

Production (TWh) |

Export (TWh) |

Electricity (TWh) |

CO2emission (Mt) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 4.59 | 322 | 2,775 | 2,452 | 113 | 36.3 |

| 2007 | 4.71 | 312 | 2,488 | 2,172 | 118 | 36.9 |

| 2008 | 4.77 | 345 | 2,555 | 2,195 | 119 | 37.6 |

| 2009 | 4.83 | 328 | 2,485 | 2,157 | 114 | 37.3 |

| 2010 | 4.89 | 377 | 2,390 | 2,004 | 123 | 39.2 |

| 2012 | 4.95 | 327 | 2,272 | 1,929 | 115 | 38.1 |

| 2012R | 5.02 | 339 | 2,313 | 1,963 | 118.7 | 36.2 |

| 2013 | 5.08 | 380 | 2,229 | 1,839 | 118.5 | 35.3 |

| Mtoe = 11,63 TWh Prim. energy includes energy losses 2012R = CO 2 calculation criteria changed, numbers updated | ||||||

Fossil fuels[]

In 2011, Norway was the eighth largest crude oil exporter in the world (at 78 Mt), and the 9th largest exporter of refined oil (at 86 Mt). It was also the world's third largest natural gas exporter (at 99 bcm), having significant gas reserves in the North Sea.[2][3] Norway also possesses some of the world's largest potentially exploitable coal reserves (located under the Norwegian continental shelf) on earth.[4]

Norway's abundant energy resources represent a significant source of national revenue. Crude oil and natural gas accounted for 40% of the country's total export value in 2015.[5] As a share of GDP, the export of oil and natural gas is approximately 17%. As a means to ensure security and mitigate against the "Dutch disease" characterized by fluctuations in the price of oil, the Norwegian government funnels a portion of this export revenue into a pension fund, the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG).[6] The Norwegian government receives these funds from their market shares within oil industries, such as their two-thirds share of Statoil, and allocates it through their government-controlled domestic economy.[6] This combination allows the government to distribute the natural resource wealth into welfare investments for the mainland. Tying this fiscal policy to the oil market for equity concerns creates a cost-benefit economic solution towards a public access good problem in which a select few are able to reap the direct benefits of a public good. Domestically, Norway has addressed the complications that occur with oil industry markets in protecting the mainland economy and government intervention in distributing its revenue to combat balance-of-payment shocks and to address energy security.[6][7]

The externalities engendered from Norway's activities on the environment, pose another concern apart from its domestic economic implications. Most of Norwegian gas is exported to European countries. As of 2020, about 20% of natural gas consumed in Europe comes from Norway, and Norwegian oil supplies 2% of the global consumption of oil.[5] Considering that three million barrels of oil adds 1.3 Mt of CO

2 per day to the atmosphere as it is consumed, 474 Mt/year, the global CO

2 impact of Norway's natural resource supply is significant.[8] Despite that, Norway exports eight times the amount of energy consumed domestically, most of Norway's carbon emissions are from its oil and gas industry (30%) and road traffic (23%).[6][7][9] To address the problem of CO

2 emissions, the Norwegian government has adopted different measures, including signing multilateral and bilateral treaties to cut its emissions in lieu of rising global environmental concerns.[9][7]

It has been argued that Norway can serve as a role model for many countries in terms of petroleum resource management. In Norway, good institutions and open and dynamic public debate involving a whole variety of civil society actors are key factors for successful petroleum governance.[10]

North Sea oil[]

In May 1963, Norway asserted sovereign rights over natural resources in its sector of the North Sea. Exploration started on July 19, 1966, when Ocean Traveller drilled its first hole. Initial exploration was fruitless, until Ocean Viking found oil on August 21, 1969. By the end of 1969, it was clear that there were large oil and gas reserves in the North Sea. The first oil field was Ekofisk, which produced 427,442 barrels of crude in 1980. Subsequently, large natural gas reserves have also been discovered and it was specifically this huge amount of oil found in the North Sea that made Norway's separate path outside the EU facile.[11]

Against the backdrop of the 1972 Norwegian referendum to not join the European Union, the Norwegian Ministry of Industry, headed by Ola Skjåk Bræk moved quickly to establish a national energy policy. Norway decided to stay out of OPEC, keep its own energy prices in line with world markets, and spend the revenue—known as the "currency gift"—in the Petroleum Fund of Norway. The Norwegian government established its own oil company, Statoil, which was raised that year,[12] and awarded drilling and production rights to Norsk Hydro and the Saga Petroleum.[citation needed]

The North Sea turned out to present many technical challenges for production and exploration, and Norwegian companies invested in building capabilities to meet these challenges. A number of engineering and construction companies emerged from the remnants of the largely lost shipbuilding industry, creating centers of competence in Stavanger and the western suburbs of Oslo. Stavanger also became the land-based staging area for the offshore drilling industry. Due to refinery needs when making special qualities of commercial oils, Norway imported NOK 3.5 billion of foreign oil in 2015.[13]

Barents Sea oil[]

In March 2005, Minister of Foreign Affairs Jan Petersen stated that the Barents Sea, off the coast of Norway and Russia, may hold one third of the world's remaining undiscovered oil and gas.[14] Also in 2005, the moratorium on exploration in the Norwegian sector, imposed in 2001 due to environmental concerns, was lifted following a change in government.[15] A terminal and liquefied natural gas plant is now[when?] being constructed at Snøhvit, it is thought that Snøhvit may also act as a future staging post for oil exploration in the Arctic Ocean.[16]

Electricity generation[]

Electricity generation in Norway is almost entirely from hydroelectric power plants. Of the total production in 2005 of 137.8 TWh, 136 TWh was from hydroelectric plants, 0.86 TWh was from thermal power, and 0.5 TWh was wind generated. In 2005 the total consumption was 125.8 TWh.[2][needs update]

Norway was the first country to generate electricity commercially using sea-bed tidal power. A 300 kilowatt prototype underwater turbine started generation in the Kvalsund, south of Hammerfest, on November 13, 2003.[17][18]

Norway and Sweden's grids have long been connected. Beginning in 1977 the Norwegian and Danish grids were connected with the Skagerrak power transmission system with a transmission capacity of 500 MW, growing to 1,700 MW in 2015.[19] Since 6 May 2008, the Norwegian and Dutch electricity grids have been interconnected by the NorNed submarine HVDC (450 kilovolts) cable with a capacity of 700 megawatts.[20]

Carbon emissions[]

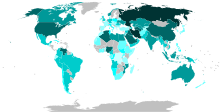

Despite producing the majority of its electricity from hydroelectric plants, Norway is ranked 30th in the 2008 list of countries by carbon dioxide emissions per capita and 37th in the 2004 list of countries by ratio of GDP to carbon dioxide emissions. Norway is a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol, under which it agreed to reduce its carbon emissions to no more than 1% above 1990 levels by 2012.

On April 19, 2007, Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg announced to the Labour Party annual congress that Norway's greenhouse gas emissions would be cut by 10 percent more than its Kyoto commitment by 2012, and that the government had agreed to achieve emission cuts of 30% by 2020. He also proposed that Norway should become carbon neutral by 2050, and called upon other rich countries to do likewise.[21] This carbon neutrality would be achieved partly by carbon offsetting, a proposal criticised by Greenpeace, who also called on Norway to take responsibility for the 500 m tonnes of emissions caused by its exports of oil and gas.[22] World Wildlife Fund Norway also believes that the purchase of carbon offsets is unacceptable, saying "it is a political stillbirth to believe that China will quietly accept that Norway will buy climate quotas abroad".[23] The Norwegian environmental activist Bellona Foundation believes that the prime minister was forced to act due to pressure from anti-European Union members of the coalition government, and called the announcement "visions without content".[23]

In January 2008 the Norwegian government went a step further and declared a goal of being carbon neutral by 2030. But the government has not been specific about any plans to reduce emissions at home; the plan is based on buying carbon offsets from other countries.[24]

Carbon capture and storage[]

Norway was the first country to operate an industrial-scale carbon capture and storage project at the Sleipner oilfield, dating from 1996 and operated by Statoil. Carbon dioxide is stripped from natural gas with amine solvents and is deposited in a saline formation. The carbon dioxide is a waste product of the field's natural gas production; the gas contains 9% CO2, more than is allowed in the natural gas distribution network. Storing it underground avoids this problem and saves Statoil hundreds of millions of euros in carbon taxes. Sleipner stores about one million tonnes of CO2 a year.[25]

See also[]

- Carbon footprint

- Climate change in Norway

- Energy policy

- European Economic Area

- Future energy development

- Natural resources of the Arctic

- Oil megaprojects (2011)

- Peak oil

- Renewable energy in Norway

References[]

- ^ IEA Key World Energy Statistics Statistics 2015, 2014 (2012R as in November 2015 + 2012 as in March 2014 is comparable to previous years statistical calculation criteria, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009 Archived 2013-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2006 Archived 2009-10-12 at the Wayback Machine IEA October, crude oil p.11, coal p. 13 gas p. 15

- ^ "Free publications" (PDF). www.iea.org.

- ^ Norway: Energy and Power, Encyclopedia of the Nations

- ^ 3000 billion tons of coal off Norway's coastline, by R.J. Wideroe & J.D.Sundberg, Energy Bulletin by Verdens Gang, 29 December 2005

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Exports of Norwegian oil and gas". Norwegianpetroleum.no.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d [1][dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Moe et al. (eds.), E.; Godzimirsk, Jakub M. "6: The Norwegian Energy Security Debate". The Political Economy of Renewable Energy and Energy Security (2014 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "How much carbon dioxide is produced from burning gasoline and diesel fuel? - FAQ - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Environmental Defense Fund; International Emissions Trading Association (May 2015). NORWAY: AN EMISSIONS TRADING CASE STUDY (2015 ed.). pp. 1–11.

- ^ Indra Overland (2018) ‘Introduction: Civil Society, Public Debate and Natural Resource Management’, in Overland, Indra. (2018). Introduction: Civil Society, Public Debate and Natural Resource Management. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60627-9_1.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ^ Einar Lie (18 January 2017). "The History of Statoil, 1972-2022 (Project)". Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History, University of Oslo. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ "Statoil hemmeligholder oljeimport". Stavanger Aftenblad. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Petersen, Jan (2005-03-05). "Transatlantic Efforts for Peace and Security". Speech to Carnegie Institution, Washington D.C. Minister of Foreign Affairs, Norway. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

The Barents Sea also contains huge energy resources – perhaps as much as one third of the world's remaining undiscovered oil and gas resources are to be found in this area

- ^ Acher, John (2005-11-16). "Norway Takes Oil Bids For Barents Sea Frontier". World Environment News Planet Ark. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ Krauss, Clifford; Myers, Steven Lee; Revkin; Romero, Simon (2005-10-10). "As Polar Ice Turns to Water, Dreams of Treasure Abound". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ "Wayback Machine". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2021-05-03. Cite uses generic title (help)

- ^ Penman, Danny (2003-09-22). "First power station to harness Moon opens". New Scientist. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ Lind, Anton. "600 kilometer søkabel skal føre strøm mellem Norge og Danmark" Danmarks Radio, 12 March 2015. Accessed: 13 March 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2008-07-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Speech to the congress of the Labour Party". Office of the Prime Minister of Norway. 2007-04-19. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2007-04-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b http://www.norwaypost.no/cgi-bin/norwaypost/imaker?id=71002 Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rosenthal, Elisabeth (2008-03-22). "Lofty Pledge to Cut Emissions Comes With Caveat in Norway". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ "SACS". www.sintef.no.

Further reading[]

- International Energy Agency (2005). Energy Policies of IEA Countries – Norway- 2005 Review. Paris: OECD/IEA. ISBN 92-64-10935-8. Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

External links[]

- Interactive Map over the Norwegian Continental Shelf, live information, facts, pictures and videos.

- Energy efficiency policies and measures in Norway 2006

- Oil and gas in the Barents Sea – A perspective from Norway

- CICERO: A green certificate market may result in less green electricity

- Lofty Pledge to Cut Emissions Comes With Caveat in Norway

- CO2STORE research project

- Map of Norway's offshore oil and gas infrastructure

- Energy in Norway

- Politics of Norway