Tekhelet

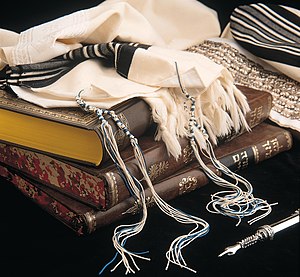

Tekhelet (Hebrew: תְּכֵלֶת; alternate spellings include tekheleth, t'chelet, techelet and techeiles) is a "blue-violet",[1] "blue",[2] or "turquoise"[3] dye highly prized by ancient Mediterranean civilizations and mentioned 49[4][5] times in the Hebrew Bible/Tanakh. It was used in the clothing of the High Priest, the tapestries in the Tabernacle, and the tzitzit (fringes) affixed to the corners of one's four-cornered garments, including the tallit.[4]

Tekhelet dye was critical for the production of certain articles in the Jerusalem Temple, as well as for the commandment of tzitzit. Tekhelet is most notably mentioned in the third paragraph of the Shema, quoting Numbers 15:37–41. However, neither the source nor method of production of Tekhelet is specified in the Bible, but according to the Tosefta[6] the Ḥillazon is the exclusive source of the dye. The Talmud further informs us that the dye of Tekhelet was produced from a marine creature known as the Ḥillazon.[7]

A garment with tzitzit has four tassels, each containing four strings. There are three opinions in rabbinic literature as to how many of the four strings should be dyed with tekhelet: two strings;[8] one string;[9] or one-half string.[10] Knowledge of how to produce tekhelet was lost in medieval times, and since then tzitzit did not include tekhelet. However, in modern times, many Jews believe they have identified the Ḥillazon and rediscovered tekhelet manufacture process, and now wear tzitzit which include the resulting blue dye.

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

Biblical references[]

Of the 49[11] or 48 [4][5] uses in the Masoretic Text, one refers to fringes on cornered garments of the whole nation of Israel (Numbers 15:37–41), 44[citation needed] refer to the priesthood or temple clothes and garments. The remaining 6[citation needed] in Esther, Jeremiah and Ezekiel are secular uses; such as when Mordechai puts on "blue and white" "royal clothing" in Esther. The color could be used in combination with other colors such as 2 Chronicles 3:14 where the veil of Solomon's Temple is made of blue-violet (Tekhelet), purple (Hebrew: אַרְגָּמָן Argaman) and scarlet (Biblical Hebrew: שָׁנִי (Shani); Late Biblical, Modern Hebrew: כַּרְמִיל karmiyl). Ezekiel 27:7 may indicate the source of the shellfish to have been the Aegean region.[12] In addition to the above observations it should be added that all of the instances of tekhelet (both secular and priestly) attribute its usage to some kind of elite. From this perspective it becomes obvious that it was difficult to obtain and expensive what is further corroborated by the later rabbinic writings.[13]

History[]

At some point following the Roman destruction of the Second Temple, the actual identity of the source of the dye was lost, and during a period of over 1,400 years, most Jews have only worn plain white tassels (Tzitzit).[14]

The stripes on prayer shawls, often black, but also blue or purple, are believed by many to symbolize the lost Tekhelet which is referred to by various sources as being "black as midnight", "blue as the midday sky", and even purple.[15] These stripes of tekhelet inspired the design of the flag of Israel.

Identifying the color of tekhelet[]

Despite the general agreement of the most of the modern English translations of the phrase, the term tekhelet itself presents several basic problems. First of all, it remains unclear to what extent the word in biblical times denoted an abstract color or the actual source material. This problem is specific neither to the tekhelet nor to the biblical Hebrew and the scholars often point to other languages which feature similar phenomena.[16] Second, although with time it came to denote the color blue solely, the exact hue in the Antiquity remains unknown. Basing on the scarce material evidence from the ancient Near East and the early biblical translations the scholars suppose that tekhelet probably belonged to the spectrum between blue, red and purple.[17]

In the Septuagint, tekhelet was translated into Greek as hyakinthos (ὑακίνθος, "hyacinth"). The color of the hyacinth flower ranges from violet blue to a bluish purple.

The early rabbinic literature in turn provide two main expositions for the color of techelet. One group of sources, including Bava Metziya 61a-b and Menachot 40a-b, mentions qala ilan, an indigo dye described as visually indistinguishable from tekhelet. Yet, although this dye was much cheaper to obtain, the rabbis cursed those who substituted techelet with some low-priced equivalent and in fact preferred to annul the obligation altogether rather than to compromise its value (Mishnah Menachot 4:1), which clearly proves that it was not the color which mattered most. The second and much more numerous group compares the tekhelet to the color of the sky or the sea which is not far off from indigo. More importantly, however, this group contains several instances (Menachot 43b, Sotah 17a, Hullin 89a, Numbers Rabbah 4:13, 17:5) which extend the comparison and liken the tekhelet to the throne of glory. Apparently, the particular features of this divine chair are not speculated in the Early Rabbinic Literature, but it can be safely assumed that, again, these were not the visual qualities which counted here but rather the extraordinary value of the object and its explicit cultic associations.[13]

Rashi describes the color of tekhelet as “poireau,” the French word for leek, transliterated into Hebrew.

In conclusion, its color varies between central sky blue in sunlight, through the iris indigo of the rainbow to deep African violet in dull weather; translated in a German translation of the biblical book of Exodus, as "blauem purpur".[citation needed]

Identifying the ḥillazon[]

Various sea creatures have been suggested as the ḥillazon, the purported source of the blue dye.[18][19][20][21]

Hexaplex trunculus[]

In his doctoral thesis (London, 1913) on the subject, Rabbi Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog (1889–1959) named Hexaplex trunculus (then known by the name "Murex trunculus") as the most likely candidate for the dye's source. Though Hexaplex trunculus fulfilled many of the Talmudic criteria, Rabbi Herzog's inability to consistently obtain blue dye (sometimes the dye was purple) from the snail precluded him from declaring it to be the dye source.

According to Zvi Koren, a professor of chemistry, Tekhelet was close in color to midnight blue.[22] This conclusion was reached based on the chemical analysis of a 2000-year old patch of dyed fabric recovered from Masada in the 1960s.[23] The sample, shown to have been dyed with Murex snail extraction, is a midnight blue with a purplish hue. Additionally, in 2013, Na'ama Sukenik of the Israel Antiquities Authority verified a 1st-century CE-dated fragment of blue-dyed fabric to have used H. trunculus as the source of its pure blue color.[24]

In the 1980s, Otto Elsner,[25] a chemist from the Shenkar College of Fibers in Israel, discovered that if a solution of the dye was exposed to ultraviolet rays, such as from sunlight, blue instead of purple was consistently produced.[26] In 1988, Rabbi Eliyahu Tavger dyed Tekhelet from H. trunculus for the Mitzvah (commandment) of Tzitzit for the first time in recent history.[27] Based on this work, four years later, the Ptil Tekhelet Organization was founded to educate about the dye production process, and to make the dye available for all who desire to use it. The television show The Naked Archaeologist interviews an Israeli scientist who also makes the claim that this mollusk is the correct animal. A demonstration of the production of the blue dye using sunlight to produce the blue color is shown. The dye is extracted from the hypobranchial gland of Hexaplex trunculus snails.[20]

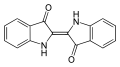

Chemically, exposure to sunlight turns the red 6,6'-dibromoindigo in snails into a mixture of blue indigo dye and blue-purple . The leuco (white) solution form of dibromoindigo loses some bromines in the ultraviolet radiation.[28]

Sepia officinalis[]

In 1887, Grand Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner, the Radziner Rebbe, researched the subject and concluded that Sepia officinalis (common cuttlefish) met many of the criteria. Within a year, Radziner chassidim began wearing Tzitzit that included threads dyed with a colorant produced from this cephalopod. Rabbi Herzog obtained a sample of this dye and had it chemically analyzed. The chemists concluded that it was a well-known synthetic dye "Prussian blue" made by reacting Iron(II) sulfate with an organic material. In this case, the cuttlefish only supplied the organic material which could have as easily been supplied from a vast array of organic sources (e. g., ox blood). R. Herzog thus rejected the cuttlefish as the Ḥillazon and some suggest that had the Grand Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner known this fact, he too would have rejected it based on his explicit criterion that the blue color must come from the animal and that all other additives are permitted solely to aid the color in adhering to the wool.[29]

Janthina[]

Within his doctoral research on the subject of Tekhelet, Herzog placed great hopes on demonstrating that Hexaplex trunculus was the genuine snail Ḥillazon. However, having failed to consistently achieve blue dye from Hexaplex trunculus, he wrote: “If for the present all hope is to be abandoned of rediscovering the Ḥillazon Shel Tekhelet in some species of the genera Murex (now "Hexaplex") and Purpura we could do worse than suggest Janthina as a not improbable identification".[30] Blue dye has in the meantime been obtained from Hexaplex trunculus snail and the pigment molecule itself is hypothesized to be Tyrian Purple or Aplysioviolin.[31] In 2002 Dr. S. W. Kaplan of Rehovot, Israel, sought to investigate Herzog's suggestion that Tekhelet came from the extract of Janthina. After fifteen years of research he concluded that Janthina was not the ancient source of the blue dye.

Gallery[]

The common cuttlefish

A sample of Prussian blue, a counterfeit blue

Hexaplex trunculus found on Israeli coastal plain near Tel Shikmona, possibly the ḥillazon of the Tosefta

Purple dye-bath with extracts from fresh Hexaplex trunculus glands

Tzitzit (tassel) with blue thread produced from Hexaplex (Murex) trunculus

Structural formula of murex-based tyrian purple, the red-purple dye present in tekhelet indigo before explosure to sunlight. (note the two bromides: in marine environments, sodium bromide is abundant, not so in terrestrial ones)

Structural formula of plant based or synthetic indigo, a counterfeit dark-blue

See also[]

- Blue in Judaism

- Tantura

- Arguman, also called Tyrian purple, a Biblical reddish purple dye from the related seasnail, Bolinus brandaris.

Bibliography[]

- Gadi Sagiv, 'Deep Blue: Notes on the Jewish Snail Fight'

- Hoffmann, Roald; Leibowitz, Shira (1997). Old wine, new flasks : reflections on science and Jewish tradition. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0716728993.

- Sterman, Baruch; Taubes, Judy (2012). The rarest blue : the remarkable story of an ancient color lost to history and rediscovered. Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-0762782222.

- KolRom Media, 'Techeiles - It's Not All Black and White'

References[]

- ^ Everett Fox, The Five Books of Moses: A New Translation with Introductions, Commentary, and Notes. New York: Schocken Books, 1995.

- ^ "Techelet (Blue Thread)". Tzitzit and Tallis. Chabad Media Center. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Chaim Miller, ed. (2006). Chumash : the five books of Moses : with Rashi's commentary Targum Onkelos and Haftaros with a commentary anthologized from classic rabbinic texts and the works of the Lubavitcher Rebge (Synagogue ed.). New York, N.Y.: Kol Menachem. p. 967. ISBN 9781934152010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zohar, Gil. "Fringe Benefits – Kfar Adumim factory revives the lost commandment of tekhelet". www.ou.org. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amir, Nina. "Lost thread of blue, tekhelet color reestablished". Religion & Spirituality. Clarity Digital Group LLC d/b/a Examiner.com. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ Tosefta Menachot9:6

- ^ Menachot 44a

- ^ Rashi, Tosafos, Rosh

- ^ Raavad

- ^ Rambam

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew: 8504. תְּכֵ֫לֶת (tekeleth) -- violet, violet thread". biblesuite.com.

- ^ Gesenius Hebrew lexicon entry for "Isles of Elisha" – more modern source needed

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kosior, Wojciech (2018-07-27). ""Like a Throne of Glory:" The Apotropaic Potential of Ṣîṣîṯ in the Hebrew Bible and Early Rabbinic Literature". Review of Rabbinic Judaism. 21 (2): 176–201. doi:10.1163/15700704-12341342. ISSN 1570-0704.

- ^ Rabbi Mois Navon. "On History, Mesorah and Nignaz" (PDF). Threads of Reason: A Collection of Essays on Tekhelet.

- ^ Simmons, Rabbi Shraga. Tallit stripes

- ^ Tomasz Sikora, “Color Symbolism in the Jewish Mysticism. Prolegomena” (Polish), Studia Judaica 12.2 (2003): 47.

- ^ Robert Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, (Chicago, 1980/2013) [TWOT] (CD-ROM), 2510.0.

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia – Page 1057 Geoffrey W. Bromiley – 2007 "The most highly prized dye in the ancient world obtained from the secretions of four molluscs native to the eastern Mediterranean: helix ianthina, murex brandaris, murex trunculus, and purpura lapillus. Various shades could be produced"

- ^ Hoffmann, Roald; Leibowitz, Shira (1997). Old wine, new flasks : reflections on science and Jewish tradition. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0716728993.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoffmann, Roald (April 19, 2012). "Indigo - A Story of Craft, Religion, History, Science and Culture". Special Collections & Archives Research Center Oregon State University Libraries. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Sterman, Baruch; Taubes, Judy (2012). The rarest blue: the remarkable story of an ancient color lost to history and rediscovered. Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-0762782222.

- ^ "The color 'techelet'". jpost.com.

- ^ Kraft, Dina (2011-02-27). "Rediscovered, Ancient Color is Reclaiming Israeli Interest". New York Times.

- ^ "Why so blue? Biblical dye was made from snails". NBC News. Associated Press. Dec 31, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Robin Ngo (11 September 2013). "What Color Was Tekhelet?". Retrieved 20 January 2014.

Decades after Herzog’s death, chemist Otto Elsner proved that murex dye could in fact produce a sky-blue color by exposing the snail secretions to ultraviolet rays during the dyeing process. Sky-blue Tzitzit, then, could be made with murex dye.

- ^ O. Elsner, "Solution of the enigmas of dyeing with Tyrian purple and the Biblical tekhelet", Dyes in history and Archaeology 10 (1992) p 14f.

- ^ Navon, Mois (December 30, 2013). "Threads of Reason-A Collection of Essays on Tekhelet" (PDF). p. 23. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

In 1985, while writing a book about Tzitzit entitled Kelil Tekhelet, R. Eliyahu Tavger became convinced that the source of authentic Tekhelet had been found. Determined to actualize his newfound knowledge, and after much trial and error, he succeeded in applying the process, according to Halakhah, from beginning to end. He thus became the first person, since the loss of the Ḥillazon, to dye Tekhelet for the purpose of Tzitzit. In 1991, together with R. Tavger, Ptil Tekhelet was formed to produce and distribute Tekhelet strings for Tzitzit.

- ^ Ramig, Keith; Lavinda, Olga; Szalda, David J.; Mironova, Irina; Karimi, Sasan; Pozzi, Federica; Shah, Nilam; Samson, Jacopo; Ajiki, Hiroko; Massa, Lou; Mantzouris, Dimitrios; Karapanagiotis, Ioannis; Cooksey, Christopher (June 2015). "The nature of thermochromic effects in dyeings with indigo, 6-bromoindigo, and 6,6′-dibromoindigo, components of Tyrian purple". Dyes and Pigments. 117: 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2015.01.025.

A more blue shade can be obtained if the reduced form of DBI, leuco-DBI, is exposed to sunlight whereupon it is debrominated. Then on oxidation, MBI and indigo are formed.

- ^ P'til T'khelet, p.168

- ^ Herzog, p.71

- ^ Kitrossky, Levi. "Do We Know Tekhelet?" (PDF).

External links[]

- Ptil Tekhelet – A group that promotes the view that the chilazon is the snail Murex trunculus.

- Explanation of how tekhelet was discovered and made from the Murex trunculus

- Jewish ritual objects

- Hebrew words and phrases in the Hebrew Bible

- Jewish religious clothing

- Non-clerical religious clothing

- Animal dyes

- Shades of blue

- Mollusc products