Terrytoons

The Terrytoons logo used during the late 1950s | |

| Industry | Animation |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Bray Productions |

| Founded | 1929 |

| Founders | Paul Terry Frank Moser Joseph Coffman |

| Defunct | 1972 |

| Fate | Closed |

| Successor | Paramount Animation |

| Headquarters | 1929–1930, Long Island, New York, United States[1]

|

Key people | Paul Houlton Terry |

Terrytoons was an animation studio in New Rochelle, New York, that produced animated cartoons for theatrical release from 1929 to 1972 (and briefly returned between 1987 and 1996 for television in name only). Terrytoons was founded by Paul Terry, Frank Moser, and Joseph Coffman, and operated out of the "K" Building in downtown New Rochelle. The studio created many cartoon characters including Mighty Mouse, Heckle and Jeckle, Gandy Goose, Sourpuss, Dinky Duck, Little Roquefort, the Terry Bears, and Luno; Terry's pre-existing character Farmer Al Falfa was also featured often in the series.

The "New Terrytoons" period of the late 1950s through the mid-1960s produced such characters as Tom Terrific, Deputy Dawg, Hector Heathcote, Hashimoto-san, Sidney the Elephant, Possible Possum, James Hound, Astronut, Sad Cat, The Mighty Heroes, and Sally Sargent.

Ralph Bakshi got his start as an animator, and eventually as a director, at Terrytoons.[2] The Terrytoons shorts were originally released to theaters by 20th Century Fox. The Terrytoons library was later purchased by CBS and is now owned by Paramount Pictures.

History[]

Before Terrytoons[]

Terry first worked for Bray Studios in 1916, where he created the Farmer Al Falfa series. He would then make a Farmer Al Falfa short for Edison Pictures, called "Farmer Al Falfa's Wayward Pup" (1917), and some later cartoons were made for Paramount Pictures.

Around 1921, Terry founded the Fables animation studio, named for its Aesop's Film Fables series, in conjunction with the studio of Amedee J. Van Beuren. Fables churned out a Fable cartoon every week for eight years in the 1920s.

In 1928, Van Beuren, anxious to compete with the new phenomenon of talking pictures, released Terry's Dinner Time (released October 1928). Van Beuren then urged Terry to start producing actual sound films, instead of post-synchronizing the cartoons. Terry refused, and Van Beuren fired him in 1929. Almost immediately, Terry and much of his staff started up the Terrytoons studio near his former studio. One staff member during that time was Art Babbitt, who went on to become a well-known Disney animator.

Peak era[]

Through much of its history, the studio was considered one of the lowest-quality houses in the field, to the point where Paul Terry noted, "Let Walt Disney be the Tiffany's of the business. I want to be the Woolworth's!"[3] Terry's studio had the lowest budgets and was among the slowest to adapt to new technologies such as sound (in about 1930) and Technicolor (in 1938). While its graphic style remained remarkably static for decades, it actually followed the sound cartoon trend of the late 1920s and early 1930s very quickly. Background music was entrusted to one man, , and Terry's refusal to pay royalties for popular songs forced Scheib to compose his own scores.

Paul Terry took pride in producing a new cartoon every other week, regardless of the quality of the films. Following the success of Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) Paul Terry considered making an animated feature film adaptation of King Lear starring Farmer Al Falfa. However, after seeing the commercial failures of Disney's Pinocchio and Fantasia (both 1940) and Max Fleischer's Mr. Bug Goes to Town (1941), he decided to abandon the project. Until 1957, screen credits were very sparse, listing only the writer (until 1950, solely John Foster; then Tom Morrison thereafter), director (Terry's three main directors were Connie Rasinski, , and ), and musician (musical director Philip A. Scheib).

Terrytoons' first distributor was Educational Pictures, specialists in short-subject comedies and novelties. Audio-Cinema in the early 1930s backed the production of Terrytoons, and distributed the Educational library internationally, except in the United Kingdom and Ireland where the library was distributed by Educational and Gaumont-British in partnership with the Ideal Film Company.

The Fox Film company (from 1935, 20th Century Fox) then released Educational shorts to theaters in the 1930s, giving the Terry cartoons wide exposure. After 20th Century-Fox withdrew its support from Educational Pictures, the company both backed and distributed Terrytoons. Farmer Al Falfa was Terry's most familiar character in the 1930s; Kiko the Kangaroo was spun off the Farmer Al Falfa series. Most of the other cartoons featured generic animal characters. One of the stock designs was a scruffy dog with a black patch around one eye; Terry ultimately built a series around this character, now known as Puddy the Pup.

Paul Terry may have realized that Educational was in financial trouble because he found another lucrative outlet for his product. In 1938, he arranged to release his older cartoons through home-movie distributor Castle Films. Educational went out of business within the year, but 20th Century Fox continued to release Terrytoons to theaters for the next two decades. With a new emphasis on "star" characters, Terrytoons featured the adventures of Super Mouse (later renamed Mighty Mouse), the talking magpies Heckle and Jeckle, silly Gandy Goose, Dinky Duck, mischievous mouse Little Roquefort, and The Terry Bears.

Despite the artistic drawbacks imposed by Terry's inflexible business policies, Terrytoons was nominated four times for the Academy Award for Animated Short Film: All Out for V in 1942, My Boy, Johnny in 1944, Mighty Mouse in Gypsy Life in 1945, and Sidney's Family Tree in 1958.

Changing hands[]

The studio was sold outright by the retiring Paul Terry to CBS in 1955, but 20th Century Fox (TCF) continued distribution. The deal closed the following year in 1956, and it became a division of the CBS Films subsidiary.[4] Later, in 1957 CBS put it under the management of UPA alumnus Gene Deitch, who had to work with even lower budgets.

Deitch's most notable works at the studio were the Tom Terrific cartoon segments for the Captain Kangaroo television show. He also introduced a number of new characters, such as ,[5] ,[6] John Doormat,[citation needed] and Clint Clobber.[7]

Before Deitch was fired in 1959, took complete control of the studio. Under his supervision, Heckle and Jeckle and Mighty Mouse went back into production. Besides the three core directors of the Terry era who were still involved as animators and directors, two Famous Studios stalwarts joined the crew, Dave Tendlar and Martin Taras. Other new theatrical cartoon series included Hector Heathcote, Luno and Hashimoto San. The studio also began producing the Deputy Dawg series for television in 1959. Another television production for the Captain Kangaroo show was The Adventures of Lariat Sam, which was written in part by Gene Wood, who would later become the announcer for several TV gameshows including Family Feud.

Phil Scheib continued as the studio's musical director through the mid-1960s when he was replaced by Jim Timmens and Elliott Lawrence.

The best-known talent at Terrytoons in the 1960s was animator/director/producer Ralph Bakshi, who started with Terrytoons in the 1950s as an opaquer,[2] and eventually helmed the Mighty Heroes series. Bakshi left Terrytoons in 1967 for Paramount, which closed its cartoon unit later that year. He would later go on to produce Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures for television in 1987.

Post-history[]

After the departure of Bakshi, the studio petered out, and finally closed in 1972. As a result of the FCC banning TV networks from owning cable television and syndication of television programs, CBS created Viacom International to handle all network programs beyond TV production and network broadcasting. On July 4, 1971, Viacom International spun off from CBS; neither Viacom International nor CBS had any interest in Terrytoons. The Terrytoons film library was still regularly re-released to theaters by Fox. The studio's last short was an unsold TV pilot called Sally Sargent, about a 16-year-old girl who is a secret agent. Soon after Sally Sargent was completed, Viacom International ended their relationship with Fox and re-releases ceased. Terrytoons’ existence soon came to an end.

, who kept the studio running after Bakshi left, would soon die along with Connie Rasinski, and Bob Kuwahara, reducing the studio to a ghost studio with executive producer Bill Weiss and story supervisor Tom Morrison; Viacom kept the studio open until 1972. By October 1972, Viacom International announced that Terrytoons will leave New Rochelle and relocate to Viacom International's office in New York City. By December 29, Viacom sold the now abandoned New Rochelle studio, and the company's fate was forever sealed.

Bill Weiss continued Terrytoons production from his New York City office with the 1970s Terrytoons cartoons (especially Mighty Mouse and Deputy Dawg) being syndicated to many local TV markets, and they were a staple of after-school and Saturday-morning cartoon shows for over three decades, from the 1950s through the 1980s, until the television rights to the library were acquired by USA Network in 1989. However, any new cartoons of the studio's stars came from other studios.[8]

In the late 1970s, Filmation Studios licensed the rights to make a new Mighty Mouse series from Viacom International. In 1987, Ralph Bakshi produced Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures, which lasted for two seasons. Bakshi and John Kricfalusi inspired the staff to try to get as much Jim Tyer-style drawing in the show as possible. Tyer, a stand-out Terry animator of the original cartoons with a unique style, became a strong influence on the artists of the Bakshi series.

In 1999, Nickelodeon attempted to revive the Terrytoons characters as part of a TV series called Curbside. Curbside would have been a parody of late-night talk shows with Heckle and Jeckle serving as hosts of the show, along with their assistant Dinky Duck, and would have featured new cartoons featuring Terrytoon characters like Deputy Dawg, Sidney the Elephant, and Mighty Mouse. However, it was never picked up, making it the only Terrytoons show that was never officially released.[9]

In 2002, the Terrytoons characters returned to television in original commercials for Brazilian blue cheese (for what is now ) and fine wine.

Through the years that have followed since the last Terrytoons TV series material in 1988, the rights have been scattered as a result of prior rights issues and the corporate changes involving Viacom and CBS.

Since CBS Corporation re-merged with Viacom to form ViacomCBS, reuniting CBS with Paramount, on December 4, 2019, Paramount Pictures now owns the theatrical distribution on behalf of Paramount Animation and CBS Entertainment Group, while CBS Media Ventures owns the television distribution to the Terrytoons film library. However, some Terrytoons shorts are believed to be in the public domain and have been issued on low-budget VHS tapes and DVDs. On January 5, 2010, the first official release of any Terrytoons material by CBS DVD was issued in the form of the complete series of Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures.

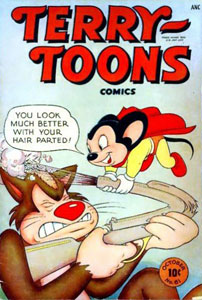

Terrytoons comic books[]

Among the many licensed Terrytoons products are comic books, mainly published throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The company's characters — including Mighty Mouse, the magpies Heckle and Jeckle, Dinky Duck, Gandy Goose, and Little Roquefort — were initially licensed to Timely, a predecessor of Marvel Comics, in 1942.[10] St. John Publications took over the license from 1947 to 1956, Pines Comics published Terrytoons comics from 1956 to 1959, Dell Comics made an attempt from 1959 to 1962 (and again later from 1966 to 1967), and finally Western Publishing published Mighty Mouse comics from 1962 all the way up to 1980.

The lead title, Terry-Toons Comics, was published by Timely from Oct. 1942–Aug. 1947.[11] With issue #60 (Sept. 1947), publication of the title was taken over by St. John Publications, which published another 27 issues until issue #86 (May 1951).[12] The series continued in 1951 (with duplicate issues #85-86) as Paul Terry's Comics, publishing another 41 issues until May 1955, when it was canceled with issue #125.[13]

Timely launched the Mighty Mouse series in 1946. The first St. John Terrytoons comic was Mighty Mouse #5 (Aug. 1947), its numbering also taken over from the Timely run. That series eventually ran 71 issues with St. John, moving to Pines for 16 issues from Apr. 1956 to Aug. 1959, to Dell for 12 issues from Oct./Dec. 1959–July/Sept. 1962, and Western for 17 issues from Oct. 1962 to Jan. 1980 (with a hiatus from Sept. 1965 to Mar. 1979), finally ending with issue #172.

St. John's Terrytoons comics include the field's first 3-D comic book, Three Dimension Comics #1 (Sept. 1953 oversize format, Oct. 1953 standard-size reprint), featuring Mighty Mouse.[14] According to Joe Kubert, co-creator with the brothers Norman Maurer and Leonard Maurer, it sold an exceptional 1.2 million copies at 25 cents apiece[15] at a time when comics cost a dime.

Dell Comics published eight issues of a New Terrytoons title from June/Aug. 1960 to March/May 1962.

Terrytoons comic book titles[]

- Adventures of Mighty Mouse (18 issues, November 1951 – May 1955) — St. John

- Dinky Duck (19 issues, November 1951 – Summer 1958) — launched by St. John, continued by Pines

- Gandy Goose (4 issues, March 1953 – November 1953) – St. John

- Heckle and Jeckle (32 issues, October 1951 – June 1959) — launched by St. John, continued by Pines

- Heckle and Jeckle (4 issues, November 1962 – August 1963) — Western Publishing

- Heckle and Jeckle (3 issues, May 1966 – 1967) — Dell

- Little Roquefort Comics (10 issues, June 1952 – Summer 1958) — launched by St. John, continued by Pines

- Mighty Mouse / Paul Terry's Mighty Mouse Comics (172 issues, Fall 1946 – January 1980) — launched by Timely; continued by St. John, Pines, Dell, and Western

- Mighty Mouse Album (3 issues, October – December 1952) — St. John

- New Terrytoons (8 issues, June/August 1960 – March/May 1962) — Dell

- Terry Bears Comics / Terrytoons, the Terry Bears (4 issues, June 1952 – Summer 1958) — launched by St. John, continued by Pines

- Terry-Toons Comics / Paul Terry's Comics (125 issues, Oct. 1942 – May 1955) — launched by Timely Comics, continued by St. John

- TerryToons Comics (9 issues, June 1952 – November 1953) — St. John; separate from Terry-Toons Comics / Paul Terry's Comics

Terrytoons staff: 1929–1972[]

(Note: Staff members besides the producer, director, writer, and musical director were left uncredited into 1957.)

Producers[]

- Paul Terry (1929–1956)

- William M. Weiss (Executive Producer; 1955–1972)

- Frank Schudde (Production Manager; 1942, 1946–1963)

Directors[]

- Cosmo Anzilotti (1965–1969)

- Ralph Bakshi (1963, 1965–1967)

- Art Bartsch (1958-1968)

- Mannie Davis (1936–1961)

- Gene Deitch (Supervising Director, 1956–1958)

- Eddie Donnelly (1936–1962)

- John Foster (1937-1938)

- George Gordon (1936–1937)

- Al Kouzel (1957–1969)

- Bob Kuwahara (1959, 1962–1964)

- Frank Moser (1929–1937)

- Connie Rasinski (1937–1965)

- Martin Taras (1959)

- Robert Taylor (1966–1972)

- Dave Tendlar (1959–1971)

- Paul Terry (1929–1938)

- Bill Tytla (1944, 1962)

- Jack Zander (1937)

- Volney White (1940-1941)

Writers[]

- Joseph Barbera

- Larz Bourne

- Tod Dockstader

- John Foster

- Dick Kinney

- Isadore Klein

- Bob Kuwahara

- Donald McKee

- Tom Morrison

- Al Stahl

- Kin Platt

- Paul Terry

- Jack Mercer

- Bernie Kahn

Animators[]

- Cosmo Anzilotti

- Art Babbitt

- George Bakes

- Ralph Bakshi

- Joseph Barbera

- Vinnie Bell

- Peggy Breese

- George Cannata

- Don Caulfield

- Al Chiarito

- Theron Collier

- Doug Crane

- Mannie Davis

- Ed Donnelly

- Dave Fern

- John Foster

- John Gentilella

- Dan Gordon

- George Gordon

- Juan Guidi

- Armand Guidi

- T. Hee

- Elizabeth Huntemann

- Isadore Klein

- Bill Kreese

- Frank Little

- Jim Logan

- Frank Moser

- John Paratore

- Ralph Pearson

- Connie Quirk

- Connie Rasinski

- Margaret Roberts

- Jerry Shields

- Larry Silverman

- Milton Stein

- Martin Taras

- Frank Tashlin

- Paul Terry

- Reuben Timmins

- Jim Tyer

- Bill Tytla

- Carlo Vinci

- Jim Whipp

- Gordon Whittier

- Volney White

- George Zaffo

- Jack Zander

- Cy Young

- Paul Sommer

- Robinson McKee

- Vivie Risto

- Dan Noonan

Design and background artists[]

- Art Bartsch

- Eli Bauer

- Robert Blanchard

- Anderson Craig

- Bill Hilliker

- W.M. Stevens

- Robert Taylor

- John Vita

- George Zaffo

- John Zago

- Lin Larsen

- Bill Tytla

- Charles Thorson

Sound directors[]

- George McAvoy

- Tom Morrison

Voice actors[]

- Elvi Allen

- Dayton Allen

- Bern Bennett

- Herschel Bernardi

- Bradley Bolke

- Roy Halee

- Margie Hines

- Betty Jaynes

- Arthur Kay

- Norma Macmillan

- Bob McFadden

- Jo Miller

- Tom Morrison

- Doug Moye

- John Myhers

- Sid Raymond

- Philip A Scheib

- Ken Schoen

- Ned Sparks

- Allen Swift

- Paul Terry

- Lionel Wilson

- Patricia Terry

Musical directors[]

- Philip A. Scheib (1930–1971)

- Jim Timmens (1964–1971)

Productions[]

- See List of Terrytoons animated shorts for complete filmography

Cartoon series[]

- Aesop's Fables (1921–1933)[16]

- Astronut (1964–1971)[17]

- Clint Clobber (1957–1959)[18]

- Dimwit (1953–1957)[19]

- Dingbat (1950)[20]

- Dinky Duck (1939–1957)[21]

- Duckwood (1964)[22]

- Fanny Zilch (1933)[23]

- Farmer Al Falfa (1915–1956)[24]

- Foofle (1959–1960)[25]

- Gandy Goose (1938–1955)[26]

- Gaston Le Crayon (1957–1959)[27]

- Good Deed Daily (1955–1956)[28]

- Half Pint (1951)[29]

- Hashimoto (1959–1963)[30]

- Heckle and Jeckle (1946–1966)[31]

- Hector Heathcote (1959–1971)[32]

- James Hound (1966–1967)[33]

- John Doormat (1957–1959)[34]

- Kiko the Kangaroo (1936–1937)[35]

- Little Roquefort (1950–1955)[36]

- Luno The White Stallion (1963–1964)[37]

- Martian Moochers (1966)[38]

- Mighty Mouse (1942–1961)[39]

- Nancy and Sluggo (1942)[40]

- Possible Possum (1965–1971)[41]

- Puddy the Pup (1935–1942)[42]

- Sad Cat (1965–1968)[43]

- Sidney the Elephant (1958–1963)[44]

- The Terry Bears (1951–1956)[45]

TV series[]

- Barker Bill's Cartoon Show (1953–1956)

- Mighty Mouse Playhouse (1955–1967)

- CBS Cartoon Theatre (1956)

- The Heckle and Jeckle Show (1956)

- Tom Terrific (1957)

- The Deputy Dawg Show (1959–1964)

- The Adventures of Lariat Sam (1962)

- The Hector Heathcote Show (1963)

- The Astronut Show (1965)

- Mighty Mouse, & The Mighty Heroes (1966–1967)

- Sally Sargent (1968) (pilot)

- Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures (1987–1988)

- Curbside (1999) (pilot)

Other media[]

Many of the characters (such as Mighty Mouse, Heckle and Jeckle, Dinky Duck, Deputy Dawg, and others) were slated to make cameos in the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, but Oscar the Timid Pig, Looey Lion, and a character resembling Gandy Goose appeared in the film. They can all be seen at the film's finale.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Terrytoon's "Club Sandwich" (1931)". Cartoon Research. Jerry Beck. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A history of American animated cartoons (Rev. ed.). New York: New American Library. ISBN 0452259932.

- ^ Hamonic, W. Gerald (2018). Terrytoons: The Story of Paul Terry and His Classic Cartoon Factory. John Libbey Publishing Ltd. p. 168. ISBN 978-0861967292.

- ^ "Chapter 15: The Terry-fying Challenge". Animation World Network. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ Sidney the Elephant at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015.

- ^ Gaston Le Crayon at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012.

- ^ Clint Clobber at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012.

- ^ "Terrytoons – The Viacom Years". Cartoon Research. Jerry Beck. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ DataBase, The Big Cartoon. "Curbside (Nickelodeon)". Big Cartoon DataBase (BCDB). Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Mitchell, Kurt; Thomas, Roy (2019). American Comic Book Chronicles: 1940-1944. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 978-1605490892.

- ^ "Terry-Toons Comics", Grand Comics Database. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- ^ "Terry-Toons Comics", Grand Comics Database. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- ^ "Paul Terry's Comics," Grand Comics Database. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- ^ Zone, Ray (n.d.). "1950s 3-D Comic Book Checklist". Ray3DZone.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009.

- ^ Joe Kubert interview, "A Myth in the World of Comics" Archived 2011-01-22 at WebCite, UniversoHQ.com, n.d. WebCitation archive.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 18–20. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 66. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 73. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 73. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 73. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 77. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 79. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 82. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 84. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 88. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 89. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 96. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 96. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 97. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 100. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 102. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 103. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 110–111. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 113. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 127. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 131. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 135. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 142–143. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terrytoons. |

- Paul Terry at IMDb

- Terrytoons at IMDb

- TerryToons at the Big Cartoon DataBase

- Post Paul Terry era filmography

- Terrytoons

- 1929 establishments in New York (state)

- 1956 mergers and acquisitions

- 1972 disestablishments in New York (state)

- 1972 mergers and acquisitions

- American animation studios

- American companies disestablished in 1972

- American companies established in 1929

- Companies based in New Rochelle, New York

- Mass media companies disestablished in 1972

- Defunct companies based in New York (state)

- Mass media companies established in 1929

- Fox animation

- ViacomCBS subsidiaries

- Paramount Pictures

- CBS Media Ventures

- Animation studios owned by ViacomCBS