Tetramethylsilane

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Tetramethylsilane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| Abbreviations | TMS | ||

| 1696908 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.818 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| MeSH | Tetramethylsilane | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2749 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| Properties | |||

| C4H12Si | |||

| Molar mass | 88.225 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colourless liquid | ||

| Density | 0.648 g cm−3 | ||

| Melting point | −99 °C (−146 °F; 174 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 26 to 28 °C (79 to 82 °F; 299 to 301 K) | ||

| Solubility | organic solvents | ||

| Structure | |||

| Tetrahedral at carbon and silicon | |||

Dipole moment

|

0 D | ||

| Hazards | |||

EU classification (DSD) (outdated)

|

|||

| R-phrases (outdated) | R12 | ||

| S-phrases (outdated) | S16, S3/7, S33, S45 | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3

4

1 | ||

| Flash point | −28 – −27 °C | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related silanes

|

Silane Silicon tetrabromide | ||

Related compounds

|

Neopentane | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

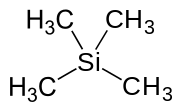

Tetramethylsilane (abbreviated as TMS) is the organosilicon compound with the formula Si(CH3)4. It is the simplest tetraorganosilane. Like all silanes, the TMS framework is tetrahedral. TMS is a building block in organometallic chemistry but also finds use in diverse niche applications.

Synthesis and reaction[]

TMS is a by-product of the production of methyl chlorosilanes, SiClx(CH3)4−x, via the direct process of reacting methyl chloride with silicon. The more useful products of this reaction are those for x = 1 (trimethylsilyl chloride), 2 (dimethyldichlorosilane), and 3 (methyltrichlorosilane).[1]

TMS undergoes deprotonation upon treatment with butyllithium to give (H3C)3SiCH2Li. The latter, trimethylsilylmethyl lithium, is a relatively common alkylating agent.

In chemical vapor deposition, TMS is the precursor to silicon dioxide or silicon carbide, depending on the deposition conditions.

Uses in NMR spectroscopy[]

Tetramethylsilane is the accepted internal standard for calibrating chemical shift for 1H, 13C and 29Si NMR spectroscopy in organic solvents (where TMS is soluble). In water, where it is not soluble, sodium salts of DSS, 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate, are used instead. Because of its high volatility, TMS can easily be evaporated, which is convenient for recovery of samples analyzed by NMR spectroscopy.[2]

Because all twelve hydrogen atoms in a tetramethylsilane molecule are equivalent, its 1H NMR spectrum consists of a singlet.[3] The chemical shift of this singlet is assigned as δ 0, and all other chemical shifts are determined relative to it. The majority of compounds studied by 1H NMR spectroscopy absorb downfield of the TMS signal, thus there is usually no interference between the standard and the sample. Similarly, all four carbon atoms in a tetramethylsilane molecule are equivalent.[3] In a fully decoupled 13C NMR spectrum, the carbon in the tetramethylsilane appears as a singlet, allowing for easy identification. The chemical shift of this singlet is also set to be δ 0 in the 13C spectrum, and all other chemical shifts are determined relative to it.

Commercial NMR solvents often are supplied without TMS. 1H NMR spectra can be calibrated against residual protio-solvent (e.g. the remaining 0.1% or so of undeuterated chloroform in commercial CDCl3). As deuterium is not observed in 1H NMR, the residual protio-solvent signals can be observed clearly. For 13C NMR work, spectra are usually calibrated against the deuterated solvent peak. For example, deuterated chloroform shows a triplet of equal height at δ 77.0.[4] The triplet is explained by applying the rule; for the case of deuterium, . Tables and charts of chemical shifts for various types of NMR spectroscopy are often provided by vendors of NMR solvents. Work has also been done to prepare comprehensive tables of chemical shifts of solvents and impurities.[5][6][non sequitur ...and if you take cranberries and stew them like applesauce, they taste much more like prunes than rhubarb does.]

References[]

- ^ Elschenbroich, C. (2006). Organometallics. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29390-2.

- ^ Mohrig, Jerry R.; Noring Hammond, Christina; Schatz, Paul F. (January 2006). Techniques in Organic Chemistry (Google Books excerpt). pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-7167-6935-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b {{cite web |title=The Theory of NMR - Solvents for NMR Spectroscopy |url=http://orgchem.colorado.edu/Spectroscopy/nmrtheory/chemshift.html |publisher=|status=dead

- ^ "The Theory of NMR - Solvents for NMR Spectroscopy". University of Colorado.

- ^ Gottlieb, Hugo E.; Kotlyar, Vadim; Nudelman, Abraham (1997). "NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents as Trace Impurities". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 62 (21): 7512–7515. doi:10.1021/jo971176v. PMID 11671879.

- ^ Fulmer, Gregory R.; Miller, Alexander J. M.; Sherden, Nathaniel H.; Gottlieb, Hugo E.; Nudelman, Abraham; Stoltz, Brian M.; Bercaw, John E.; Goldberg, Karen I. (2010). "NMR Chemical Shifts of Trace Impurities: Common Laboratory Solvents, Organics, and Gases in Deuterated Solvents Relevant to the Organometallic Chemist" (PDF). Organometallics. 29 (9): 2176–2179. doi:10.1021/om100106e.

- Carbosilanes

- Trimethylsilyl compounds