The Constitution of the United States: is it pro-slavery or anti-slavery?

"The Constitution of the United States: is it pro-slavery or anti-slavery?" is a speech that was given on March 26, 1860, in Glasgow, in which Frederick Douglass rejects arguments made by slaveholders as well as fellow abolitionists as to the nature and meaning of the United States Constitution. Due to its popularity, the speech was later published as a pamphlet.[1]

Background[]

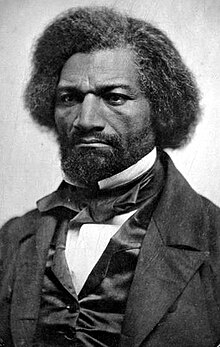

Frederick Douglass, born into slavery, escaped and upon meeting Garrisonian abolitionists joined their ranks. Highly intelligent and capable, Douglass became an active leader and founded The North Star newspaper.

As editor of The North Star, Douglass examined many issues of the day including the text and history of the United States Constitution. Over time, Douglass had a well-publicized break with Garrisonian principles and announced[2] his change of opinion in the North Star with respect to the Constitution as "a pro-slavery document." A decade later, the raid at Harper's Ferry left Douglass accused as a supporter of the raid, which led him to flee the country. While on a lecture tour in Canada and later Great Britain, Douglass and British Garrisonian abolitionist George Thompson debated about the contents and nature of the United States Constitution in front of an interested public.[3] Prior to Douglass' arrival Thompson organized several lectures to denounce Douglass.[4][5] Douglass was known to be fond of public controversy and explaining his beliefs as only he could.[6]

Historian Vernon Loggins believed that this speech "provided a picture of the range of Douglass's oratory" unique among his other works.[7]

Speech[]

Douglass used the allegory of the "man from another country" during the speech,[8] arguing that abolitionists should take a moment to examine the plainly written text of the Constitution instead of secret meanings, saying that "it is not whether slavery existed ... at the time of the adoption of the Constitution" nor that "those slaveholders, in their hearts, intended to secure certain advantages in that instrument for slavery."[9] This was a reference to Roger Taney's view that the Constitution was pro-slavery,[10] which was the view of most well-trained lawyers at the time.

Douglass articulated his belief that the "great national enactment done by the people" "can only be altered, amended, or added to by the people," and that the ambiguity of many of its clauses leaned against the flimsy evidence offered by slaveholders.[11]

He argued in the speech for a reform and not a breakup of government, saying "Do you break up your government? By no means. You say:- Reform the government; and that is just what the abolitionists who wish for liberty in the United States propose."[12] Douglass saw no need to break up the government, because he denied "that the constitution guarantees the right to hold property in man."[13]

During the speech, Douglass examined point by point four provisions mentioned as evidence by Thompson: Article 1, section 9; Article 4, section 2; Article 1, section 2; and Article 1, section 8. In each instance, Douglass took a provision[14] and elaborated a worst-case argument and his own argument.[15] He asked if Thompson even read the actual Constitution. Regarding slave insurrections, he argued that the process of putting down an insurrection necessarily meant putting an end to slavery itself, since the institution was a never ending source of new potential insurrections.[16][17] He also examined point by point the meaning of the objects contained in the Preamble, which are union, defense, welfare, tranquility, justice, and liberty. Douglass concludes that of the six objects slavery is the "foe of them all."[18]

Historians reactions[]

The speech has received glowing reviews from historians, who note Douglass' "power of mature reasoning" in this "majestic" speech,[19] They have noted Douglass' "ingenius textual interpretation of the Constitution".[20]

Bibliography[]

Loggin, Vernon. The Negro author: his development in America to 1900 (1931)

References[]

- ^ Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July, note 7

- ^ Frederick Douglass Project Writings: Change of Opinion Announced

- ^ Divided Hearts: Britain and the American Civil War

- ^ Advocates of Freedom: African American Transatlantic Abolitionism in the British Isles

- ^ Frederick Douglass: A Biography, by Philip S. Foner, p. 407

- ^ Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, David W. Blight

- ^ Reading Abolition: The Critical Reception of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Frederick Douglass

- ^ Bonds of Citizenship: Law and the Labors of Emancipation

- ^ Slavery and Sacred Texts: The Bible, the Constitution, and Historical Consciousness in Antebellum America

- ^ THE CANONS OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW, page 2

- ^ Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July

- ^ A Documentary History of the American Civil War Era, Volume 2

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to the United States Constitution

- ^ A Glorious Liberty: Frederick Douglass and the Fight for an Antislavery Constitution

- ^ Processes of Constitutional Decisionmaking

- ^ Legal Canons

- ^ Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July

- ^ “SLAVEHOLDERS AND THEIR NORTHERN ABETTORS”: FREDERICK DOUGLASS’S LONG CONSTITUTIONAL JOURNEY

- ^ What Do You Think, Mr. Ramirez? - The American Revolution in Education, Geoffrey Galt Harpham

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to the United States Constitution

External links[]

- 19th-century speeches

- Speeches by Frederick Douglass