The Cure (1995 film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

| The Cure | |

|---|---|

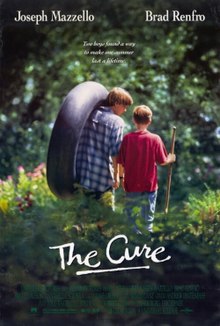

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Horton |

| Written by | Robert Kuhn |

| Produced by | Mark Burg Eric Eisner |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Andrew Dintenfass |

| Edited by | Anthony Sherin |

| Music by | Dave Grusin |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million |

| Box office | $2.57 million (US)[1] |

The Cure is a 1995 American drama film directed by Peter Horton and written by Robert Kuhn. The film stars Brad Renfro and Joseph Mazzello who play two teenage boys searching for the cure for AIDS from which one of them is suffering.

The film was distributed by Universal Pictures Studios and it was first released on April 21, 1995. The Cure failed to generate profits, earning $2.57 million at the box office[2] - nearly half a million shy of their $3 million budget. There have been mixed reviews from critics, but the film has nevertheless been received warmly by the general audience, often described as "touching."[3][4]

In 1995 Horton received the Audience Award at the Cinekid Festival and Renfro Best Performance by a Young Actor in a Drama Film at the First Annual YoungStar Awards. The film was also nominated at the 38th Annual Grammy Awards for the soundtrack's instrumental composition and also nominated in two categories for the Young Artist Award.[3]

Plot[]

Erik is a 13-year-old adolescent loner who has just moved to a small town in Stillwater, Minnesota. Accompanying Erik is his newly divorced, emotionally abusive and neglectful workaholic mother, Gail. Erik and his 11-year-old neighbour Dexter, who contracted HIV through a blood transfusion, become good friends despite their initial distaste and differences, as Erik seeks the familial relationships that he grew up without, in Dexter and his mother Linda. Erik hides the friendship from his mother, knowing that she won't approve due to her own prejudice regarding AIDS.

Gail discovers the friendship one night after Linda comes over to ask Erik about something Dexter ate in the boys' quest to find a natural cure for his disease. She furiously warns Linda to keep Dexter away, but Linda encourages the friendship. When the boys read an article in a tabloid about a doctor in distant New Orleans who claims to have found a cure for AIDS, they set out on their own down the Mississippi River with the hope of finding a means of saving Dexter's life.

The boys take a boat down the river with a bunch of degenerates, who don't treat the pair very well. Eventually the boys steal their money and try to hitchhike the rest of the way. When the boatmen find that their money has been stolen, they locate the kids at a bus station and proceed to chase them until they reach a dead end in a dilapidated building. Erik draws a switchblade and one of the men draw a knife. Dexter suddenly grabs the knife from Erik, and cuts his hand to cause himself to bleed. He threatens the boatman with his blood, saying that he has AIDS and could easily transfer the disease to him through the man's open wounds. Dexter then chases the boatmen off, threatening them with his bleeding hand. Dexter then realises what he has done by directly exposing his blood to the outside environment. He suddenly feels sick, so Erik escorts him back to the bus station. Realising that their journey must end if Dexter is to be treated, Erik resorts to calling Linda to have her pick the boys up when they reach Stillwater by bus.

Once they return, Dexter spends the rest of his time in the hospital. Erik stays with Linda, knowing that not only will Gail be angry, but she will not let him visit Dexter in the hospital. The boys joke and prank the doctors three times that Dexter has died, but when a third doctor arrives to check on him, Dexter really has died. While driving Erik home, Linda notices a mother holding her young child while crossing the street. Reminded of her own son, she pulls over and breaks down crying. Erik apologises to her, saying that he should have tried harder to find a cure. Linda, taken aback by his comment, embraces Erik, explaining that he was the happiest thing in Dexter's difficult life. Upon their arrival at home, a furious Gail confronts the pair. When Gail starts to hit Erik, Linda quickly intervenes, angrily and tearfully informs her of Dexter's death, and demands that she allow Erik to attend the funeral and never hit him again and threatens to report her to child protective services. Realising everything, Gail guiltily complies.

At Dexter's funeral, Erik places one of his shoes in the coffin and takes one of Dexter's to let sail down the river. He pays homage to an earlier moment in their trip when Dexter is having nightmares, Erik told Dexter to hold one of his sneakers as a reminder that he's always by his side.

Cast[]

- Brad Renfro as Erik

- Joseph Mazzello as Dexter

- Diana Scarwid as Gail

- Annabella Sciorra as Linda

- Aeryk Egan as Tyler

- Nicky Katt as "Pony"

- Renee Humphrey as Angle

- Bruce Davison as Dr. Jensen

- Andrew Broder as Tyler's Friend #1

- Jeremy Howard as Tyler's Friend #2

Production[]

The script for the film was written in 1993, and production began in 1994. Initially few studio executives were confident in the film's ability to be successful, but most liked the script. Sally Field wanted to direct and star and was trying to mount an offer when Steven Spielberg read the script as a writing sample, but then decided to try buying it and offered the writer a two script deal. This sparked a bidding war that ended two days later with a million dollar sale to Eric Eisner of Island Pictures. Eisner's first chose director Martin Brest declined, as he was worried about how to get the performances of young actors. Other directors who declined were Sydney Pollack, Rob Reiner and Paul Brickman.

The film's total budget was planned to be more than $20 million, but when Universal Pictures - who had signed on to distribute the film - expressed concern that no director had been signed on, Eisner hired Peter Horton to direct the film. Horton decided to cut the budget to just $10 million, making it a low budget film. To ensure the film's popularity, Horton hoped for a star to boost the box office returns and asked his ex-wife Michelle Pfeiffer and actress Meg Ryan to participate, both of whom refused. Horton was nervous to work with children, because he doubted the ability of young actors to express the emotional weight needed for the film, but was blown away by the auditions of both Mazzello and Renfro.

Some studio executives complained about the script's irresponsibility in its treatment of homosexuality. One of them refused to negotiate the film, calling it "homophobic." Particular criticism was directed towards one scene in which neighbourhood bullies insult Dexter, calling him "faggot", and that throughout the film gay characters are treated with disdain. In an analysis of the character, reviewer Jess Cagle said: "Jerry's homosexuality is apparent only in a slight part of Peter Moore's performance. The result is an effeminate character who is at best secretly gay, at worst an offensive stereotype."

The creators point out that in the aftermath of Erik telling Dexter he needs to join in his homophobia so "no one will think you're one too," Dexter refuses, saying they've been nice to him, then decides to stop playing with Erik by lying that he's busy. This unexpected rejection has a profound affect on Erik. Later in the movie, he happily plays board games with Dexter and the gay nurse Jerry. The biggest dilemma for the filmmakers was that Erik's transformation could not be realized by the audience unless it was obvious that nurse Jerry was gay, but how could they make his gayness obvious without edging close to stereotype?

Soundtrack[]

The original soundtrack to the film was composed by Dave Grusin and released on CD by GRP Records the same year as the film.

Tommy Morgan contributed to the musical harmony and Michael Fisher worked with percussion. The instruments used in the martial band of the track are: piano, electric bass, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, synthesizer and alto flute. The song called "My Great Escape" was written and performed by Marc Cohn. However, this song has never been released in any medium outside of this movie.

In an analysis for Artist Direct, Rovi Jason Ankeny commented: "The soft strings of music and the playful wind instruments sweetly capture the innocence of childhood without the traffic of sentimentality." Grusin's unusual gift for evoking particular moments in place and time is Most importantly, he deals with the subject of the film [...] with admirable moderation, avoiding saccharine in favor of drawing light from the heart, organic melodies that celebrate the Life instead of mourning their loss."

Due to critical acclaim, The Cure's soundtrack earned a nomination for Best Instrumental Composition Written For Film Or Telefilm at the 1996 Grammy Awards.

Reception[]

Box Office[]

Upon the film's initial release, The Cure debuted at #13 and grossed $1.2 million - almost half its original budget cost during its full opening weekend. Across 832 theatres in the US and Canada, the film's lifetime grosses totalled to $2,568,425. It performed better in Japan grossing more than $4.5 million in its first three weeks of release.[5]

Critical response[]

The Cure received mixed reviews from critics. It achieved a score of 45% based on 11 reviews on Rotten Tomatoes.[4]

Lisa Schwarzbaum from Entertainment Weekly gave a positive review, stating "Mazzello is naturally captivating and Renfro especially, is a remarkably instinctive young actor...What makes us cry is not that Dexter has AIDS, but that Dexter and Erik have each other to the end, until death separates them. It is an odd feat to create a dramatic story that brings us to tears even without worrying about AIDS. "The Cure" achieved this miracle."[6]

Peter Stack in "The San Francisco Chronicle" called it "A loving, funny and wistful film... Surprisingly sunny. Joseph Mazello and Brad Refro are superb."[7]

Joey O'Bryan of The Austin Chronicle gave a mixed review; "There are a few good, effective moments in 'The Cure,' but all too often there are lapses in the movie ... In the end, the good intentions of the film are Rarely performed and the good message of this family movie (children with AIDS are people too!) Is sadly delivered with a faint breath of homophobia, then subtracts another half of the star to the absurd placement of 'Butterfinger' products in your face and what you have left is a deliberate, high conceptual competence, family entertainment, [coming-of-age story], with a tear pulled from AIDS that occasionally Works like a commercial candy bar."[8]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave a negative review, stating that "There are several passages that are very touching. [...] I was derailed by the nonsense and the conviction of the movie that is funny to deal with."[9]

Leonard Klady of Variety gave a mostly negative review, criticising the film as being predictable and manipulative, stating that "Director Peter Horton is more assured with his artists, particularly the young protagonists, the strength he brings to the material lies in the development of his relationship. "The Cure" is filled with anecdote that propels the story to its inevitable conclusion, but the wholly absurd plot turns into take-off and the film never recovers."[10]

Stephen Holden of The New York Times gave a mixed review, stating that "When 'The Cure' focuses on the rites of childhood, it evokes with intense clarity the special blend of innocence, curiosity, Although the film is diligently casting itself at a higher level than the typical television sickness movie of the week, it occasionally has lapses in its sentimentality. And his image of the ravages of AIDS is very softened, being reduced to occasional symptoms, and occasional bouts of mild cough. Director Peter Horton and screenwriter Robert Kuhn have created it is a film of pre-teen friends, whose moving emotional appeal does not depend on the fact that one of the main characters has a fatal illness."[11]

Kevin Thomas from The Los Angeles Times gave a mixed review. He wrote "[It] works as a drama on friendship and its challenges, but has too many loose ends, too much that hasn't been thoroughly thought out. [...] toward the finish, "The Cure" gets into gear at last but too late to redeem earlier flaws. Despite all these flaws, actor Peter Horton, in his feature directing debut, does elicit beautifully drawn and sustained portrayals from his young actors and also from Sciorra. All told, "The Cure" plays more like a movie made for TV than the big screen."[12]

Accolades[]

| Awards | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Category | Recipient(s) | Outcome |

| Cinekid Festival | Audience Award | Peter Horton | Won |

| YoungStar Awards | Best Performance by a Young Actor in a Drama Film | Brad Renfro | Won |

| Grammy Awards | Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or for Television | Dave Grusin | Nominated |

| Young Artist Awards | Best Family Feature - Drama | The Cure | Nominated |

| Best Young Leading Actor - Feature Film | Joseph Mazzello Brad Renfro |

Nominated | |

Home media[]

The film was released in DVD on November 23, 2004 and also in Blu-Ray on March 23, 2021 in Japan only.

References[]

- ^ The Cure at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "The Cure (1995) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ a b The Cure, 21 April 1995, retrieved 2019-04-23

- ^ a b The Cure (1995), retrieved 2019-04-23

- ^ Hindes, Andrew (September 11, 1995). "Japanese savvy turns 'Cure' into hit". Variety. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (April 21, 1995). "The Cure". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ "Friendship Fuels Boys' Quest for a 'Cure'". 21 April 1995.

- ^ O'Bryan, Joey (April 21, 1995). "Movie Review: The Cure". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Cure Movie Review & Film Summary (1995) | Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (1995-04-13). "The Cure". Variety. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (1995-04-21). "FILM REVIEW; Two Boys in Quest of a Cure". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ "MOVIE REVIEW : Two Young Friends Seek 'The Cure' in AIDS Drama". Los Angeles Times. 1995-04-21. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Cure (1995 film) |

- The Cure at IMDb

- The Cure at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1995 films

- English-language films

- 1990s comedy-drama films

- American films

- American comedy-drama films

- American buddy drama films

- Films about children

- Films about death

- Films about emotions

- Films about families

- Films about friendship

- Films set in Minnesota

- Films shot in Minnesota

- HIV/AIDS in American films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films scored by Dave Grusin

- 1995 comedy films

- 1995 drama films

- Mother and son films