The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan

| The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Bob Dylan | ||||

| Released | May 27, 1963 | |||

| Recorded | April 24–25, July 9, October 16, November 1 and 15, December 6, 1962, and April 24, 1963 | |||

| Studio | Columbia Studio A, 799 Seventh Avenue, New York City[1][2] | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 50:04 (44:14 on early 1st pressings) | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Bob Dylan chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan | ||||

| ||||

The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan is the second studio album by American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, released on May 27, 1963 by Columbia Records. Whereas his self-titled debut album Bob Dylan had contained only two original songs, this album represented the beginning of Dylan's writing contemporary words to traditional melodies. Eleven of the thirteen songs on the album are Dylan's original compositions. It opens with "Blowin' in the Wind", which became an anthem of the 1960s, and an international hit for folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary soon after the release of the album. The album featured several other songs which came to be regarded as among Dylan's best compositions and classics of the 1960s folk scene: "Girl from the North Country", "Masters of War", "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" and "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right".

Dylan's lyrics embraced news stories drawn from headlines about the Civil Rights Movement and he articulated anxieties about the fear of nuclear warfare. Balancing this political material were love songs, sometimes bitter and accusatory, and material that features surreal humor. Freewheelin' showcased Dylan's songwriting talent for the first time, propelling him to national and international fame. The success of the album and Dylan's subsequent recognition led to his being named as "Spokesman of a Generation", a label Dylan repudiated.

The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan reached number 22 in the US (eventually going platinum), and became a number-one album in the UK in 1965. In 2003, the album was ranked number 97 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. In 2002, Freewheelin' was one of the first 50 recordings chosen by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry.

Recording sessions[]

Neither critics nor the public took much notice of Dylan's self-titled debut album, Bob Dylan, which sold only 5,000 copies in its first year, just enough to break even. In a pointed rebuke to John Hammond, who had signed Dylan to Columbia Records, some within the company referred to the singer as "Hammond's Folly"[3] and suggested dropping his contract. Hammond defended Dylan vigorously and was determined that Dylan's second album should be a success.[4] The recording of Freewheelin' took place from April 1962 to April 1963, and the album was assembled from eight recording sessions in the Columbia Records Studio A, 799 Seventh Avenue, in New York City.[5]

Political and personal background[]

Many critics have noted the extraordinary development of Dylan's songwriting immediately after completing his first album. One of Dylan's biographers Clinton Heylin connects the sudden increase in lyrics written along topical and political lines to the fact that Dylan had moved into an apartment on West 4th Street with his girlfriend Suze Rotolo (1943-2011) in January 1962.[6] Rotolo's family had strong left-wing political commitments; both of her parents were members of the American Communist Party.[7] Dylan acknowledged her influence when he told an interviewer: "Suze was into this equality-freedom thing long before I was. I checked out the songs with her."[8]

Dylan's relationship with Rotolo also provided an important emotional dynamic in the composition of the Freewheelin' album. After six months of living with Dylan, Rotolo agreed to her mother's proposal that she travel to Italy to study art.[9][a 1] Dylan missed her and wrote long letters to her conveying his hope that she would return soon to New York.[10] She postponed her return several times, finally coming back in January 1963. Critics have connected the intense love songs expressing longing and loss on Freewheelin' to Dylan's fraught relationship with Rotolo.[11] In her autobiography, Rotolo explains that musicians' girlfriends were routinely described as "chicks", and she resented being regarded as "a possession of Bob, who was the center of attention".[12]

The speed and facility with which Dylan wrote topical songs attracted the attention of other musicians in the New York folk scene. In a radio interview on WBAI in June 1962, Pete Seeger described Dylan as "the most prolific songwriter on the scene" and then asked Dylan how many songs he had written recently. Dylan replied, "I might go for two weeks without writing these songs. I write a lot of stuff. In fact, I wrote five songs last night but I gave all the papers away in some place called the Bitter End."[13] Dylan also expressed the impersonal idea that the songs were not his own creation. In an interview with Sing Out! magazine, Dylan said, "The songs are there. They exist all by themselves just waiting for someone to write them down. I just put them down on paper. If I didn't do it, somebody else would."[14]

Recording in New York[]

Dylan began work on his second album at Columbia's Studio A in New York on April 24, 1962. The album was provisionally entitled Bob Dylan's Blues, and as late as July 1962, this would remain the working title.[15] At this session, Dylan recorded four of his own compositions: "Sally Gal", "The Death of Emmett Till", "Rambling, Gambling Willie", and "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues". He also recorded two traditional folk songs, "Going To New Orleans" and "Corrina, Corrina", and Hank Williams' "(I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle".[16]

Returning to Studio A the following day, Dylan recorded his new song about fallout shelters, "Let Me Die In My Footsteps". Other original compositions followed: "Rocks and Gravel", "Talking Hava Negiliah Blues", "Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues", and two more takes of "Sally Gal". Dylan recorded cover versions of "Wichita", Big Joe Williams' "Baby, Please Don't Go", and Robert Johnson's "Milk Cow's Calf's Blues".[16] Because Dylan's songwriting talent was developing so rapidly, nothing from the April sessions appeared on Freewheelin'.[5]

The recording sessions at Studio A resumed on July 9, when Dylan recorded "Blowin' in the Wind", a song that he had first performed live at Gerde's Folk City on April 16.[17] Dylan also recorded "Bob Dylan's Blues", "Down the Highway", and "Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance", all of which ended up on Freewheelin', plus one other original composition, "Baby, I'm in the Mood for You", which did not.[18]

At this point, music manager Albert Grossman began to take an interest in Dylan's business affairs. Grossman persuaded Dylan to transfer the publishing rights of his songs from Duchess Music, whom he had signed a contract with in January 1962, to Witmark Music, a division of Warner's music publishing operation. Dylan signed a contract with Witmark on July 13, 1962.[19] Unknown to Dylan, Grossman had also negotiated a deal with Witmark. This gave Grossman fifty percent of Witmark's share of the publishing income generated by any songwriter Grossman had brought to the company. This "secret deal" resulted in a bitter legal battle between Dylan and Grossman in the 1980s.[20]

Albert Grossman became Dylan's manager on August 20, 1962.[21] Since Dylan was under twenty-one when he had signed his contract with CBS, Grossman argued that the contract was invalid and had to be re-negotiated. Instead, Hammond responded by inviting Dylan to his office and persuading him to sign a "reaffirment"—agreeing to abide by the original contract. This effectively neutralized Grossman's strategy, and led to some animosity between Grossman and Hammond.[22] Grossman enjoyed a reputation in the folk scene of being commercially aggressive, generating more income and defending his clients' interests more fiercely than "the nicer, more amateurish managers in the Village".[23] Dylan critic Andy Gill has suggested that Grossman encouraged Dylan to become more reclusive and aloof, even paranoid.[24]

On September 22, Dylan appeared for the first time at Carnegie Hall, part of an all-star hootenanny. On this occasion, he premiered his new composition "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall",[25] a complex and powerful song built upon the question and answer refrain pattern of the traditional British ballad "Lord Randall". "Hard Rain" would gain added resonance one month later, when President Kennedy appeared on national television on October 22, and announced the discovery of Soviet missiles on the island of Cuba, initiating the Cuban Missile Crisis. In the sleeve notes on the Freewheelin' album, Nat Hentoff quotes Dylan as saying that he wrote "Hard Rain" in response to the Cuban Missile Crisis: "Every line in it is actually the start of a whole new song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn't have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one".[26] In fact, Dylan had written the song more than a month before the crisis broke.

Dylan resumed work on Freewheelin' at Columbia's Studio A on October 26, when a major innovation took place—Dylan made his first studio recordings with a backing band. Accompanied by Dick Wellstood on piano, Howie Collins and Bruce Langhorne on guitar, Leonard Gaskin on bass, and Herb Lovelle on drums, Dylan recorded three songs. Several takes of Dylan's "Mixed-Up Confusion" and Arthur Crudup's "That's All Right Mama" were deemed unusable,[27] but a master take of "Corrina, Corrina" was selected for the final album. An 'alternate take' of "Corrina, Corrina" from the same session would also be selected for the b-side of "Mixed Up Confusion", Dylan's first electric single issued later in the year. At the next recording session on November 1, the band included Art Davis on bass, while jazz guitarist George Barnes replaced Howie Collins. "Mixed-Up Confusion" and "That's All Right Mama" were re-recorded, and again the results were deemed unsatisfactory. A take of the third song, "Rocks and Gravel", was selected for the album, but the track was subsequently dropped.[28]

On November 14, Dylan resumed work with his backup band, this time with Gene Ramey on bass, devoting most of the session to recording "Mixed-Up Confusion". Although this track did not appear on Freewheelin', it was released as a single on December 14, 1962, and then swiftly withdrawn.[29] Unlike the other material which Dylan recorded between 1961 and 1964, "Mixed-Up Confusion" attempted a rockabilly sound. Cameron Crowe described it as "a fascinating look at a folk artist with his mind wandering towards Elvis Presley and Sun Records".[30]

Also recorded on November 14 was the new composition "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" (Clinton Heylin writes that, although the sleeve notes of Freewheelin' describe this song as being accompanied by a backing band, no band is audible on the released version).[26][31] Langhorne then accompanied Dylan on three more original compositions: "Ballad of Hollis Brown", "Kingsport Town", and "Whatcha Gonna Do", but these performances were not included on Freewheelin'.[28]

Dylan held another session at Studio A on December 6. Five songs, all original compositions, were recorded, three of which were eventually included on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan: "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall", "Oxford Town", and "I Shall Be Free". Dylan also made another attempt at "Whatcha Gonna Do" and recorded a new song, "Hero Blues", but both songs were ultimately rejected and left unreleased.[28]

Traveling to England[]

Twelve days later, Dylan made his first trip abroad. British TV director Philip Saville had heard Dylan perform in Greenwich Village, and invited him to take part in a BBC television drama: Madhouse on Castle Street. Dylan arrived in London on December 17. In the play, Dylan performed "Blowin' in the Wind" and two other songs.[32] Dylan also immersed himself in the London folk scene, making contact with the Troubadour folk club organizer Anthea Joseph and folk singers Martin Carthy and Bob Davenport. "I ran into some people in England who really knew those [traditional English] songs," Dylan recalled in 1984. "Martin Carthy, another guy named [Bob] Davenport. Martin Carthy's incredible. I learned a lot of stuff from Martin."[33]

Carthy taught Dylan two English songs that would prove important for the Freewheelin' album. Carthy's arrangement of "Scarborough Fair" would be used by Dylan as the basis of his own composition, "Girl from the North Country". A 19th-century ballad commemorating the death of Sir John Franklin in 1847, "Lady Franklin's Lament", gave Dylan the melody for his composition "Bob Dylan's Dream". Both songs displayed Dylan's fast-growing ability to take traditional melodies and use them as a basis for highly personal songwriting.[34]

From England, Dylan traveled to Italy, and joined Albert Grossman, who was touring with his client Odetta.[35] Dylan was also hoping to make contact with his girlfriend, Suze Rotolo, unaware that she had already left Italy and was on her way back to New York. Dylan worked on his new material, and when he returned to London, Martin Carthy received a surprise: "When he came back from Italy, he'd written 'Girl From the North Country'; he came down to the Troubadour and said, 'Hey, here's "Scarborough Fair"' and he started playing this thing."[36]

Returning to New York[]

Dylan flew back to New York on January 16, 1963.[37] In January and February, he recorded some of his new compositions in sessions for the folk magazine Broadside, including a new anti-war song, "Masters of War", which he had composed in London.[38][39] Dylan was happy to be reunited with Suze Rotolo, and he persuaded her to move back into the apartment they had shared on West 4th Street.[40]

Dylan's keenness to record his new material for Freewheelin' paralleled a dramatic power struggle in the studio: Albert Grossman's determination to have John Hammond replaced as Dylan's producer at CBS. According to Dylan biographer Howard Sounes, "The two men could not have been more different. Hammond was a WASP, so relaxed during recording sessions that he sat with feet up, reading The New Yorker. Grossman was a Jewish businessman with a shady past, hustling to become a millionaire."[22]

Because of Grossman's hostility to Hammond, Columbia paired Dylan with a young, African-American jazz producer, Tom Wilson. Wilson recalled: "I didn't even particularly like folk music. I'd been recording Sun Ra and Coltrane ... I thought folk music was for the dumb guys. [Dylan] played like the dumb guys, but then these words came out. I was flabbergasted."[41] At a recording session on April 24, produced by Wilson, Dylan recorded five new compositions: "Girl from the North Country", "Masters of War", "Talkin' World War III Blues", "Bob Dylan's Dream", and "Walls of Red Wing". "Walls of Red Wing" was ultimately rejected, but the other four were included in a revised album sequence.[42]

The final drama of recording Freewheelin' occurred when Dylan was scheduled to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show on May 12, 1963. Dylan had told Sullivan he would perform "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues", but the "head of program practices" at CBS Television informed Dylan that this song was potentially libelous to the John Birch Society, and asked him to perform another number. Rather than comply with TV censorship, Dylan refused to appear on the show.[43] There is disagreement between Dylan's biographers about the consequences of this censorship row. Anthony Scaduto writes that after The Ed Sullivan Show debacle, CBS lawyers were alarmed to discover that the controversial song was to be included on Dylan's new album, only a few weeks from its release date. They insisted that the song be dropped, and four songs ("John Birch", "Let Me Die In My Footsteps", "Rambling Gambling Willie", "Rocks and Gravel") on the album were replaced with Dylan's newer compositions recorded in April ("Girl from the North Country", "Masters of War", "Talkin' World War III Blues", "Bob Dylan's Dream"). Scaduto writes that Dylan felt "crushed" by being compelled to submit to censorship, but he was in no position to argue.[44]

According to biographer Clinton Heylin, "There remains a common belief that [Dylan] was forced by Columbia to pull 'Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues' from the album after he walked out on The Ed Sullivan Show." However, the "revised" version of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan was released on May 27, 1963; this would have given Columbia Records only two weeks to recut the album, reprint the record sleeves, and press and package enough copies of the new version to fill orders. Heylin suggests that CBS had probably forced Dylan to withdraw "John Birch" from the album some weeks earlier and that Dylan had responded by recording his new material on April 24.[45] Whether the songs were substituted before or after The Ed Sullivan Show, critics agree that the new material gave the album a more personal feel, distanced from the traditional folk-blues material which had dominated his first album, Bob Dylan.[46]

A few copies of the original pressing of the LP with the four deleted tracks have turned up over the years, despite Columbia's supposed destruction of all copies during the pre-release phase (all copies found were in the standard album sleeve with the revised track selection). Other permutations of the Freewheelin' album include versions with a different running order of the tracks on the album, and a Canadian version of the album that listed the tracks in the wrong order.[47][48] The original pressing of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan is considered the most valuable and rarest record in America,[48] with one copy having sold for $35,000.[49]

Songs and themes[]

Side one[]

"Blowin' in the Wind"[]

"Blowin' in the Wind" is among Dylan's most celebrated compositions. In his sleeve notes for The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991, John Bauldie writes that it was Pete Seeger who first identified the melody of "Blowin' in the Wind" as Dylan's adaptation of the old Negro spiritual "No More Auction Block". According to Alan Lomax's The Folk Songs of North America, the song originated in Canada and was sung by former slaves who fled there after Britain abolished slavery in 1833. In 1978, Dylan acknowledged the source when he told journalist Marc Rowland: "'Blowin' in the Wind' has always been a spiritual. I took it off a song called 'No More Auction Block'—that's a spiritual and 'Blowin' in the Wind' follows the same feeling."[50] Dylan's performance of "No More Auction Block" was recorded at the Gaslight Cafe in October 1962, and appeared on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991.

Critic Andy Gill wrote: "'Blowin' in the Wind' marked a huge jump in Dylan's songwriting: for the first time, Dylan discovered the effectiveness of moving from the particular to the general. Whereas 'The Ballad of Donald White' would become completely redundant as soon as the eponymous criminal was executed, a song as vague as 'Blowin' in the Wind' could be applied to just about any freedom issue. It remains the song with which Dylan's name is most inextricably linked, and safeguarded his reputation as a civil libertarian through any number of changes in style and attitude."[51]

"Blowin' in the Wind" became world-famous when Peter, Paul and Mary issued the song as a single three weeks after the release of Freewheelin'. They and Dylan both shared the same manager: Albert Grossman. The single sold a phenomenal three hundred thousand copies in the first week of release. On July 13, 1963, it reached number two on the Billboard chart with sales exceeding one million copies.[52] Dylan later recalled that he was astonished when Peter Yarrow told him he was going to make $5,000 from the publishing rights.[30]

"Girl from the North Country"[]

There has been much speculation in print about the identity of the girl in "Girl from the North Country". Clinton Heylin states that the most frequently mooted candidates are Echo Helstrom, an early girlfriend of Dylan from his hometown of Hibbing, and Suze Rotolo, for whom Dylan was pining as he finished the song in Italy.[53] Howard Sounes suggests the girl Dylan probably had in mind was Bonnie Beecher, a girlfriend of Dylan's when he was at the University of Minnesota.[54][a 2] Musicologist Todd Harvey notes that Dylan not only took the tune of "Scarborough Fair", which he learned from Martin Carthy in London but also adapted the theme of that song. "Scarborough Fair" derives from "The Elfin Knight" (Child Ballad Number 2), which was first transcribed in 1670. In the song, a supernatural character poses a series of questions to an innocent, requesting her to perform impossible tasks. Harvey points out that Dylan "retains the idea of the listener being sent upon a task, a northern place setting, and an antique lyric quality".[55] Dylan returned to this song on Nashville Skyline (1969), recording it as a duet with Johnny Cash, and he returned to it again in the studio with an unreleased organ and sax version in 1978.

"Masters of War"[]

A scathing song directed against the war industry, "Masters of War" is based on Jean Ritchie's arrangement of "Nottamun Town", an English riddle song. It was written in late 1962 while Dylan was in London; eyewitnesses (including Martin Carthy and Anthea Joseph) recall Dylan performing the song in folk clubs at the time. Ritchie would later assert her claim on the song's arrangement; according to one Dylan biography, the suit was settled when Ritchie received $5,000 from Dylan's lawyers.[56]

"Down the Highway"[]

Dylan composed "Down the Highway" in the form of a 12-bar blues. In the sleeve notes of Freewheelin', Dylan explained to Nat Hentoff: "What made the real blues singers so great is that they were able to state all the problems they had; but at the same time, they were standing outside of them and could look at them. And in that way, they had them beat."[26] Into this song, Dylan injected one explicit mention of an absence that was troubling him: the sojourn of Suze Rotolo in Perugia: "My baby took my heart from me/ She packed it all up in a suitcase/ Lord, she took it away to Italy, Italy."

"Bob Dylan's Blues"[]

"Bob Dylan's Blues" begins with a spoken intro where Dylan describes the origins of folk songs in a satirical vein: "most of the songs that are written uptown in Tin Pan Alley, that's where most of the folk songs come from nowadays".[57] What follows has been characterized as an absurd, improvised blues[57] which Dylan, in the sleeve notes, describes as "a really off-the-cuff-song. I start with an idea and then I feel what follows. Best way I can describe this one is that it's sort of like walking by a side street. You gaze in and walk on."[26] Harvey points out that Dylan subsequently elaborated this style of self-deprecatory, absurdist humor into more complex songs, such as "I Shall Be Free No.10" (1964).[58]

"A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall"[]

Dylan was only 21 years old when he wrote one of his most complex songs, "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall", often referred to as "Hard Rain". Dylan is said to have premiered "Hard Rain" at the Gaslight Cafe, where Village performer Peter Blankfield recalled: "He put out these pieces of loose-leaf paper ripped out of a spiral notebook. And he starts singing ['Hard Rain'] ... He finished singing it, and no one could say anything. The length of it, the episodic sense of it. Every line kept building and bursting".[59] Dylan performed "Hard Rain" days later at Carnegie Hall on September 22, 1962, as part of a concert organized by Pete Seeger. The song gained added resonance during the Cuban Missile Crisis, just one month after Dylan's first performance of "Hard Rain", when U.S. President John F. Kennedy gave his warning to the Soviet Union over their deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. Critics have interpreted the lyric 'hard rain' as a reference to nuclear fallout, but Dylan resisted the specificity of this interpretation. In a radio interview with Studs Terkel in 1963, Dylan said,

"No, it's not atomic rain, it's just a hard rain. It isn't the fallout rain. I mean some sort of end that's just gotta happen … In the last verse, when I say, 'the pellets of poison are flooding the waters', that means all the lies that people get told on their radios and in their newspapers."[60]

Many people were astonished by the power and complexity of this work. For Robert Shelton, who had given Dylan an important boost in his 1961 review in The New York Times, this song was "a landmark in topical, folk-based songwriting. Here blooms the promised fruit of the 1950s poetry-jazz fusion of Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, and Rexroth."[61] Folk singer Dave Van Ronk later commented: "I was acutely aware that it represented the beginning of an artistic revolution."[62] Pete Seeger expressed the opinion that this song would last longer than any other written by Dylan.[63]

Side two[]

"Don't Think Twice, It's All Right"[]

Dylan wrote "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" on hearing from Suze Rotolo that she was considering staying in Italy indefinitely,[64] and he used a melody he adapted from Paul Clayton's song "Who's Gonna Buy You Ribbons (When I'm Gone)".[65] In the Freewheelin' sleeve notes, Dylan comments: "It isn't a love song. It's a statement that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better. It's as if you were talking to yourself."

Dylan's contemporaries hailed the song as a masterpiece: Bob Spitz quotes Paul Stookey saying "I thought it was a masterful statement", while Dave Van Ronk called it "self-pitying but brilliant".[66][67] Dylan biographer Howard Sounes commented: "The greatness of the song was in the cleverness of the language. The phrase "don't think twice, it's all right" could be snarled, sung with resignation, or delivered with an ambiguous mixture of bitterness and regret. Seldom have the contradictory emotions of a thwarted lover been so well expressed, and the song transcended the autobiographical origins of Dylan's pain."[68]

"Bob Dylan's Dream"[]

"Bob Dylan's Dream" was based on the melody of the traditional "Lady Franklin's Lament", in which the title character dreams of finding her husband, Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin, alive and well. (Sir John Franklin had vanished on an expedition searching for the North West Passage in 1845; a stone cairn on King William Island detailing his demise was found by a later expedition in 1859.) Todd Harvey points out that Dylan transforms the song into a personal journey, yet he retains both the theme and the mood of the original ballad. The world outside is depicted as stormy and harsh, and Dylan's most fervent wish, like Lady Franklin's, is to be reunited with departed companions and to relive the fond memories they represent.[69]

"Oxford Town"[]

"Oxford Town" is Dylan's sardonic account of events at the University of Mississippi in September 1962. U.S. Air Force veteran James Meredith was the first black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, in Oxford, Mississippi. When Meredith first tried to attend classes at the school, some Mississippians pledged to keep the university segregated, including the state governor Ross Barnett. Ultimately, the University of Mississippi had to be integrated with the help of U.S. federal troops. Dylan responded rapidly: his song was published in the November 1962 issue of Broadside.[70]

"Talkin' World War III Blues"[]

The "talkin' blues" was a style of improvised songwriting that Woody Guthrie had developed to a high plane. (A Minneapolis domestic recording that Dylan made in September 1960 includes his performances of Guthrie's "Talking Columbia" and "Talking Merchant Marine".)[71] "Talkin' World War III Blues" was a spontaneous composition Dylan created in the studio during the final session for The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. He recorded five takes of the song and the fifth was selected for the album. The format of the "talkin' blues" permitted Dylan to address the serious subject of nuclear annihilation with humor, and "without resorting to his finger-pointing or apocalyptical-prophetic persona".[71]

"Corrina, Corrina"[]

"Corrina, Corrina" was recorded by the Mississippi Sheiks, and by their leader Bo Carter in 1928. The song was covered by artists as diverse as Bob Wills, Big Joe Turner, and Doc Watson. Dylan's version borrows phrases from a few Robert Johnson songs: "Stones In My Passway", "32-20 Blues", and "Hellhound On My Trail".[72] An alternate take of the song was used as a B-side for his "Mixed-Up Confusion" single.[73]

"Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance"[]

"Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance" is based on "Honey, Won't You Allow Me One More Chance?", a song dating back to the 1890s that was popularized by Henry Thomas in his 1928 recording. "However, Thomas's original provided no more than a song title and a notion", writes Heylin, "which Dylan turned into a personal plea to an absent lover to allow him 'one more chance to get along with you.' It is a vocal tour de force and ... showed a Dylan prepared to make light of his own blues by using the form itself."[74]

"I Shall Be Free"[]

"I Shall Be Free" is a rewrite of Lead Belly's "We Shall Be Free", which was performed by Lead Belly, Sonny Terry, Cisco Houston, and Woody Guthrie. According to Todd Harvey, Dylan's version draws its melody from the Guthrie recording but omits its signature chorus ("We'll soon be free/When the Lord will call us home").[75] Critics have been divided about the worth of this final song. Robert Shelton dismissed the song as "a decided anticlimax. Although the album has at least a half dozen blockbusters, two of the weakest songs are tucked in at the end, like shirttails."[76] Todd Harvey has argued that by placing the song at the close of the Freewheelin' LP, Dylan ends on a note of levity which is a relief after the weighty sentiments expressed in several songs on the album.[77]

Outtakes[]

The known outtakes from the Freewheelin' album are as follows. All songs released in 1991 on The Bootleg Series 1–3 are discussed in that album's liner notes,[50] while songs that have never been released have been documented by biographer Clinton Heylin,[2] except where noted. All songs written by Bob Dylan, except where noted.

| hideTitle | Status |

|---|---|

| "Baby, I'm in the Mood for You" | Released on Biograph[30] and on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes", issued by "Resurfaced Records" in 2018 |

| "Baby, Please Don't Go" (Big Joe Williams) |

Released on iTunes' Exclusive Outtakes From No Direction Home EP[78] and on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. |

| "Corrine, Corrina" | Two alternative takes released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. |

| "Ballad of Hollis Brown" | Freewheelin' sessions recordings released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. Re-recorded for Dylan's next album, The Times They Are a-Changin'. Demo version released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964[79]

Dylan and Mike Seeger recorded a duet version for Seeger's album "Third Annual Farewell Reunion" (Rounder Records, 1994). |

| "The Death of Emmett Till" | Freewheelin' sessions recordings released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes", issued by "Resurfaced Records" in 2018. Recording for "Broadside Show" on WBAI-FM, May 1962, released on Folkways Records' Broadside Ballads, Vol. 6: Broadside Reunion under pseudonym Blind Boy Grunt.[80][81] Demo version released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964[79] |

| "Hero Blues" | Freewheelin' sessions recordings unreleased. Demo version released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964[79] |

| "Going to New Orleans" | Released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes", issued by "Resurfaced Records" in 2018. Takes 1 and 2 released on The 50th Anniversary Collection Vol. 1) |

| "(I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle" (Hank Williams, Jimmie Davis) |

Released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. (Take 2 released on The 50th Anniversary Collection Vol. 1) |

| "Kingsport Town" (traditional) |

Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

| "Let Me Die In My Footsteps" | Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

| "Milk Cow's Calf's Blues" (Robert Johnson) |

Released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. (Takes 1, 3, and 4 released on The 50th Anniversary Collection Vol. 1) |

| "Mixed-Up Confusion" | Released as a single, but quickly withdrawn. Later released in 1985 on Biograph[30] and on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. |

| "Quit Your Lowdown Ways" | Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

| "Rambling, Gambling Willie" | Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

| "Rocks and Gravel" | Studio version released on soundtrack CD of US TV series True Detective episode one, ("The Long Bright Dark" 2014). Acoustic version released as a live recording from The Gaslight Cafe, October 1962, on Live at the Gaslight 1962[82][83] (Takes 2 and 3 released on The 50th Anniversary Collection Vol. 1 and on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018.) |

| "Sally Gal" | Released on No Direction Home: The Bootleg Series Vol. 7.[84] Two takes released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. |

| "Talkin' Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues" | Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

| "Talkin' Hava Negiliah Blues" | Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

| "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues" | Freewheelin' sessions recordings released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes", issued by "Resurfaced Records" in 2018. Released as a live recording from Carnegie Hall, October 26, 1963, on The Bootleg Series 1–3. Demo version released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964[79] |

| "That's All Right (Mama)" (Arthur Crudup) |

Two takes released on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. (Takes 1, 3, 5 and "Remake Overdub CO76893-3" released on The 50th Anniversary Collection Vol. 1) |

| "Walls of Red Wing" | Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

| "Whatcha Gonna Do" | Freewheelin' sessions recordings unreleased. Demo version released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964[79] and on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018. |

| "Wichita (Goin' to Louisiana)" (traditional) |

Unreleased (Takes 1 and 2 released on The 50th Anniversary Collection Vol. 1 and on "The Freewheelin' Outtakes" in 2018.) |

| "Worried Blues" (traditional) |

Released on The Bootleg Series 1–3 |

Release[]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A–[86] |

| MusicHound Rock | 4.5/5[89] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Tom Hull | A–[90] |

| Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

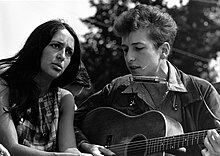

Dylan promoted his upcoming album with radio appearances and concert performances. In May 1963, Dylan performed with Joan Baez at the Monterey Folk Festival, where she joined him on stage for a duet of a new Dylan song, "With God on Our Side". Baez was at the pinnacle of her fame, having appeared on the cover of Time magazine the previous November. The performance not only gave Dylan and his songs a new prominence, it also marked the beginning of a romantic relationship between Baez and Dylan, the start of what Dylan biographer Sounes termed "one of the most celebrated love affairs of the decade".[56]

The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan was released at the end of May. According to Scaduto, it was an immediate success, selling 10,000 copies a month and bringing Dylan an income of about $2,500 a month.[91] An article by Nat Hentoff on folk music appeared in the June issue of Playboy magazine and devoted considerable space to Dylan's achievements, calling him "the most vital of the younger citybillies".[91]

In July, Dylan appeared at the second Newport Folk Festival. That weekend, Peter, Paul and Mary's rendition of "Blowin' in the Wind" reached number two on Billboard's pop chart. Baez was also at Newport, appearing twice on stage with Dylan. The combination of the chart success of "Blowin' in the Wind", and the glamor of Baez and Dylan singing together generated excitement about Dylan and his new album. Tom Paxton recalled: "That was a big breakout festival for Bob. The buzz kept growing exponentially and it was like a coronation of Bob and Joan. They were King and Queen of the festival".[92] His friend Bob Fass recalled that after Newport, Dylan told him that "suddenly I just can't walk around without a disguise. I used to walk around and go wherever I wanted. But now it's gotten very weird. People follow me into the men's room just so they can say that they saw me pee."[93]

In September, the album entered Billboard's album charts; the highest position Freewheelin' reached was number 22, but it eventually came to sell one million copies in the U.S.[94] Dylan himself came to acknowledge Freewheelin' as the album that marked the start of his success. During his dispute with Albert Grossman, Dylan stated in a deposition: "Although I didn't know it at the time, the second album was destined to become a great success because it was to include 'Blowin' in the Wind'."[95] Besides "Blowin' in the Wind", "Masters of War", "Girl from the North Country", "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" and "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" have all been acclaimed as masterpieces, and they have been mainstays of Dylan's performing repertory to the present day.[96] The album's balance between serious subject matter and levity, earnest finger-pointing songs and surreal jokes captured a wide audience, including The Beatles, who were on the cusp of global success. John Lennon recalled: "In Paris in 1964 was the first time I ever heard Dylan at all. Paul got the record (The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan) from a French DJ. For three weeks in Paris we didn't stop playing it. We all went potty about Dylan."[97]

The album was re-issued in 2010 as part of The Original Mono Recordings, a Columbia Legacy box set that included the monaural versions of Dylan's first eight albums.[98]

Artwork[]

The album cover features a photograph of Dylan with Suze Rotolo. It was taken in February 1963—a few weeks after Rotolo had returned from Italy—by CBS staff photographer Don Hunstein at the corner of Jones Street and West 4th Street in the West Village, New York City, close to the apartment where the couple lived at the time.[99] In 2008, Rotolo described the circumstances surrounding the famous photo to The New York Times: "He wore a very thin jacket, because image was all. Our apartment was always cold, so I had a sweater on, plus I borrowed one of his big, bulky sweaters. On top of that I put on a coat. So I felt like an Italian sausage. Every time I look at that picture, I think I look fat."[100] In her memoir, A Freewheelin' Time, Rotolo analyzed the significance of the cover art:

It is one of those cultural markers that influenced the look of album covers precisely because of its casual down-home spontaneity and sensibility. Most album covers were carefully staged and controlled, to terrific effect on the Blue Note jazz album covers ... and to not-so great-effect on the perfectly posed and clean-cut pop and folk albums. Whoever was responsible for choosing that particular photograph for The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan really had an eye for a new look.[101]

Critic Janet Maslin summed up the iconic impact of the cover as "a photograph that inspired countless young men to hunch their shoulders, look distant, and let the girl do the clinging".[102]

In popular culture[]

The album's iconic cover photo was carefully recreated by Cameron Crowe for his 2001 Tom Cruise-starring film Vanilla Sky[103] and by Todd Haynes for his 2007 Dylan biopic I'm Not There.[104] It also served as a visual reference for the Coen brothers' 2013 film Inside Llewyn Davis.[105]

A copy of the vinyl album itself is an important prop in Jacques Rivette's 1969 film L'Amour fou. In one key scene, the male lead, Sebastien (Jean-Pierre Kalfon), is in the apartment of his girlfriend, Marta (Josée Destoop), helping her sort through LPs she could potentially re-sell in order to raise some quick cash. He holds up her copy of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, which she declines to sell on the grounds that she still listens to it.[106]

Taylor Swift cited the album as the inspiration for her song "Betty" on Folklore. As "Betty"'s co-writer, The National's Aaron Dessner explained to Vulture, "She wanted it to have an early Bob Dylan, sort of a Freewheelin' Bob Dylan feel".[107]

Legacy[]

The success of Freewheelin' transformed the public perception of Dylan. Before the album's release, he was one among many folk-singers. Afterwards, at the age of 22, Dylan was regarded as a major artist, perhaps even a spokesman for disaffected youth. As one critic described the transformation, "In barely over a year, a young plagiarist had been reborn as a songwriter of substance, and his first album of fully realized original material got the 1960s off their musical starting block."[108] Janet Maslin wrote of the album: "These were the songs that established him as the voice of his generation—someone who implicitly understood how concerned young Americans felt about nuclear disarmament and the growing Civil Rights Movement: his mixture of moral authority and nonconformity was perhaps the most timely of his attributes."[109]

This title of "Spokesman of a Generation" was viewed by Dylan with disgust in later years. He came to feel it was a label that the media had pinned on him, and in his autobiography, Chronicles, Dylan wrote: "The press never let up. Once in a while I would have to rise up and offer myself for an interview so they wouldn't beat the door down. Later an article would hit the streets with the headline "Spokesman Denies That He's A Spokesman". I felt like a piece of meat that someone had thrown to the dogs."[110]

The album secured for Dylan an "unstoppable cult following" of fans who preferred the harshness of his performances to the softer cover versions released by other singers.[5] Richard Williams has suggested that the richness of the imagery in Freewheelin' transformed Dylan into a key performer for a burgeoning college audience hungry for a new cultural complexity: "For students whose exam courses included Eliot and Yeats, here was something that flattered their expanding intellect while appealing to the teenage rebel in their early-sixties souls. James Dean had walked around reading James Joyce; here were both in a single package, the words and the attitude set to music."[111] Andy Gill adds that in the few months between the release of Freewheelin' in May 1963, and Dylan's next album The Times They Are A-Changin' in January 1964, Dylan became the hottest property in American music, stretching the boundaries of what had been previously viewed as a collegiate folk music audience.[112]

Critical opinion about Freewheelin' has been consistently favorable in the years since its release. Dylan biographer Howard Sounes called it "Bob Dylan's first great album".[56] In a survey of Dylan's work published by Q magazine in 2000, the Freewheelin' album was described as "easily the best of [Dylan's] acoustic albums and a quantum leap from his debut—which shows the frantic pace at which Dylan's mind was moving." The magazine went on to comment, "You can see why this album got The Beatles listening. The songs at its core must have sounded like communiques from another plane."[113]

For Patrick Humphries, "rarely has one album so effectively reflected the times which produced it. Freewheelin' spoke directly to the concerns of its audience. and addressed them in a mature and reflective manner: it mirrored the state of the nation."[108] Stephen Thomas Erlewine's verdict on the album in the AllMusic guide was: "It's hard to overestimate the importance of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, the record that firmly established Dylan as an unparalleled songwriter ... This is rich, imaginative music, capturing the sound and spirit of America as much as that of Louis Armstrong, Hank Williams, or Elvis Presley. Dylan, in many ways, recorded music that equaled this, but he never topped it."[85]

In March 2000, Van Morrison told the Irish rock magazine Hot Press about the impact that Freewheelin' made on him: "I think I heard it in a record shop in Smith Street. And I just thought it was incredible that this guy's not singing about 'moon in June' and he's getting away with it. That's what I thought at the time. The subject matter wasn't pop songs, ya know, and I thought this kind of opens the whole thing up ... Dylan put it into the mainstream that this could be done."[114]

Freewheelin' was one of 50 recordings chosen by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry in 2002. The citation read: "This album is considered by some to be the most important collection of original songs issued in the 1960s. It includes "Blowin' in the Wind," the era's popular and powerful protest anthem."[115] The following year (2003), Rolling Stone Magazine ranked it number 97 on their list of the 500 greatest albums of all time,[94] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list,[116] before dropping to number 255 in a 2020 revised list.[117]

The album was included in Robert Christgau's "Basic Record Library" of 1950s and 1960s recordings, published in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981).[118] It was also included in Robert Dimery's 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[119] It was voted number 127 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[120]

Track listing[]

All tracks are written by Bob Dylan, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Recorded | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Blowin' in the Wind" | July 9, 1962 | 2:48 |

| 2. | "Girl from the North Country" | April 24, 1963 | 3:22 |

| 3. | "Masters of War" | April 24, 1963 | 4:34 |

| 4. | "Down the Highway" | July 9, 1962 | 3:27 |

| 5. | "Bob Dylan's Blues" | July 9, 1962 | 2:23 |

| 6. | "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" | December 6, 1962 | 6:55 |

| Total length: | 23:29 | ||

| No. | Title | Recorded | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" | November 14, 1962 | 3:40 |

| 2. | "Bob Dylan's Dream" | April 24, 1963 | 5:03 |

| 3. | "Oxford Town" | December 6, 1962 | 1:50 |

| 4. | "Talkin' World War III Blues" | April 24, 1963 | 6:28 |

| 5. | "Corrina, Corrina" (traditional) | October 26, 1962 | 2:44 |

| 6. | "Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance" (

| July 9, 1962 | 2:01 |

| 7. | "I Shall Be Free" | December 6, 1962 | 4:49 |

| Total length: | 26:35 | ||

Note Some very early first pressing copies contained four songs that were ultimately replaced by Columbia on all subsequent pressings. These songs were "Rocks and Gravel", "Let Me Die in My Footsteps," "Rambling Gambling Willie" and "Talkin' John Birch Blues". Copies of the "original" version of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (in both mono and stereo) are extremely rare.

The original track listing was as follows:

| No. | Title | Recorded | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Blowin' in the Wind" | July 9, 1962 | 2:46 |

| 2. | "Rocks and Gravel" | November 1, 1962 | 2:21 |

| 3. | "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" | December 6, 1962 | 6:48 |

| 4. | "Down the Highway" | July 9, 1962 | 3:10 |

| 5. | "Bob Dylan's Blues" | July 9, 1962 | 2:19 |

| 6. | "Let Me Die in My Footsteps" | April 25, 1962 | 4:05 |

| Total length: | 21:29 | ||

| No. | Title | Recorded | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" | November 14, 1962 | 3:37 |

| 2. | "Gamblin' Willie's Dead Man's Hand" | April 24, 1962 | 4:11 |

| 3. | "Oxford Town" | December 6, 1962 | 1:47 |

| 4. | "Corrina, Corrina" (Traditional) | October 26, 1962 | 2:42 |

| 5. | "Talkin' John Birch Blues" | April 24, 1962 | 3:45 |

| 6. | "Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance" (

| July 9, 1962 | 1:57 |

| 7. | "I Shall Be Free" | December 6, 1962 | 4:46 |

| Total length: | 22:45 | ||

Personnel[]

Additional musicians[]

- Howie Collins – guitar on "Corrina, Corrina"

- Leonard Gaskin – double bass on "Corrina, Corrina"

- Bruce Langhorne – guitar on "Corrina, Corrina"

- Herb Lovelle – drums on "Corrina, Corrina"

- Dick Wellstood – piano on "Corrina, Corrina"

Technical[]

- John H. Hammond – production

- Nat Hentoff – liner notes

- Don Hunstein – album cover photographer

- Tom Wilson – production

Charts[]

| Chart (1963) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard 200[121] | 22 |

| Chart (1964) | Peak position |

| UK Albums Chart[122] | 1 |

| Chart (2020) | Peak position |

| Portuguese Albums (AFP)[123] | 33 |

Certifications[]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[124] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[125] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes[]

- ^ Rotolo writes that "my mother did not approve of Bob at all. He paid her no homage and she paid him none". Rotolo suspected that her mother presented her with the trip to Italy "as a fait accompli" to lure her away from her relationship with Dylan. See Rotolo 2009, p. 169

- ^ An important recording of Dylan playing traditional material was taped in Beecher's apartment in December 1961. Misnamed the "Minneapolis Hotel Tape", the songs were released on the Great White Wonder bootleg. See Gray 2006, pp. 590–591. Beecher subsequently married counter-cultural figure Wavy Gravy.

Footnotes[]

- ^ Heylin 1995, pp. 13–19

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heylin 1996, pp. 30–43

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 31, track 3.

- ^ Scaduto 2001, p. 110

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gray 2006, pp. 243–244

- ^ Heylin 2000, pp. 88–89

- ^ Rotolo 2009, pp. 26–40

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 90

- ^ Rotolo 2009, pp. 168–169

- ^ Rotolo 2009, pp. 171–181

- ^ Heylin 2000, pp. 99–101

- ^ Rotolo 2009, p. 254

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 92

- ^ Sing Out!, October–November 1962, quoted in Sounes 2001, p. 122

- ^ Heylin 2000, pp. 98–99

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heylin 1996, p. 30

- ^ Heylin 1996, p. 29

- ^ Heylin 1996, p. 32

- ^ Heylin 2000, pp. 94–95

- ^ Sounes 2001, pp. 118–119

- ^ Gray 2006, p. 284

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sounes 2001, p. 124

- ^ Gray 2006, p. 283

- ^ Gill 1999, p. 20

- ^ Heylin 1996, p. 33

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hentoff 1963

- ^ Heylin 1996, pp. 33–34

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Heylin 1996, p. 34

- ^ Heylin 1996, p. 35

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Crowe 1985

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 104

- ^ BBC TV 2007

- ^ Loder, Kurt (1984), "Interview with Kurt Loder, Rolling Stone", reprinted in Cott 2006, pp. 295–296

- ^ Heylin 2000, pp. 106–107

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 127

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 110

- ^ Heylin 1996, p. 40

- ^ Harvey 2001, p. 142

- ^ Heylin 2009, p. 117

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 114

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 115

- ^ Heylin 1996, p. 43

- ^ Heylin 1996, p. 44

- ^ Scaduto 2001, p. 141

- ^ Heylin 2000, pp. 114–117

- ^ Scaduto 2001, p. 142

- ^ Gray 2006, p. 244

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson 2002, pp. 12–13

- ^ Sharp 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bauldie 1991

- ^ Gill 1999, p. 23

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 135

- ^ Heylin 2009, pp. 120–121

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 47

- ^ Harvey 2001, pp. 33–34

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sounes 2001, p. 132

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shelton 2003, p. 155

- ^ Harvey 2001, p. 17

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 102

- ^ Terkel, Studs (1963). "Radio Interview with Studs Terkel, WFMT (Chicago)," reprinted in Cott 2006, pp. 6–7

- ^ Shelton 2003, pp. 155–156

- ^ Gill 1999, p. 31

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 122

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 101

- ^ Harvey 2001, p. 24

- ^ Spitz 1989, pp. 199–200

- ^ Harvey 2001, pp. 25–26

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 120

- ^ Harvey 2001, p. 19

- ^ Gill 1999, pp. 32–33

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harvey 2001, p. 103

- ^ Harvey 2001, pp. 20–22

- ^ Shelton 2003, pp. 173, 178

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 99

- ^ Harvey 2001, p. 50

- ^ Shelton 2003, p. 157

- ^ Harvey 2001, p. 52

- ^ Three Song Sampler 2005

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Escott 2010

- ^ Heylin 1995, p. 11

- ^ Broadside Ballads, Vol. 6: Broadside Reunion

- ^ Browne 2005

- ^ Collette 2005

- ^ Gorodetsky 2005

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erlewine

- ^ Flanagan 1991

- ^ Brackett & Hoard 2004, p. 262

- ^ Bob Dylan: The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (eds) (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 369. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Hull, Tom (June 21, 2014). "Rhapsody Streamnotes: June 21, 2014". tomhull.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scaduto 2001, p. 144

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 136

- ^ Heylin 2000, p. 120

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levy 2005

- ^ Dylan's deposition of October 15, 1984, in the case Albert B. Grossman et al. vs. Bob Dylan; quoted in Sounes 2001, p. 132

- ^ Sounes 2001, p. 133

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 114

- ^ Kirby, David (October 21, 2010). "Bob Dylan unfiltered: Fall tour brings new releases, old recordings". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Carlson 2006

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony (May 11, 2008). "Memoirs of a Girl From the East Country (O.K., Queens)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2011. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Rotolo 2009, p. 217

- ^ Miller 1981, p. 221

- ^ Nobody. "The Freewheelin Bob Dylan". Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Suze Rotolo: A Freewheelin' Time". AUX. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ "It's Cold Outside: The Style of Llewyn Davis". Classiq – An online journal that celebrates cinema, culture, style and storytelling. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ michaelgloversmith (May 21, 2012). "A Decalogue of the Dopest Dylan References in Movies". White City Cinema. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ Gerber, Brady (July 27, 2020). "The Story Behind Every Song on Taylor Swift's folklore". Vulture. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Humphries 1991, p. 43

- ^ Miller 1981, p. 220

- ^ Dylan 2004, p. 119

- ^ Williams 1992, p. 53

- ^ Gill 1999, p. 37

- ^ Harris 2000, p. 138

- ^ Heylin 2003, p. 134

- ^ The Library of Congress 2002

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Stone, Rolling; Stone, Rolling (September 22, 2020). "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "A Basic Record Library: The Fifties and Sixties". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899190251. Retrieved March 16, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (March 23, 2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (2006). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 82. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan – Bob Dylan: Awards at AllMusic. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ "Bob Dylan: Albums". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan". Hung Medien. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ "British album certifications – Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin Bob Dylan". British Phonographic Industry.Select albums in the Format field. Select Gold in the Certification field. Type The Freewheelin Bob Dylan in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ "American album certifications – Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin_ Bob Dylan". Recording Industry Association of America.

References[]

- Bauldie, John (1991). The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991 (booklet). Bob Dylan. New York: Columbia Records.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. Cassell & Co. ISBN 0-304-35605-0.

- Björner, Olof (October 21, 2010). "Still on the Road: 1962 Concerts and Recording Sessions". Bjorner.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2010.

- "Bob Dylan: The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan". Acclaimedmusic.net. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (Media notes) (4th ed.). Fireside. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Archived from the original on October 12, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- "Broadside Ballads, Vol. 6: Broadside Reunion". Folkways Records. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Browne, David (October 30, 2005). "EW reviews: Kanye West and Bob Dylan". CNN. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- Carlson, Jen (April 18, 2006). "NYC Album Art: The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan". Gothamist. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- Collette, Doug (November 12, 2005). "Bob Dylan: No Direction Home & Live at the Gaslight 1962". Allaboutjazz.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- Cott, Jonathan, ed. (2006). Dylan on Dylan: The Essential Interviews. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-92312-1.

- Crowe, Cameron (1985). Biograph (booklet). Bob Dylan. New York: Columbia Records.

- Dylan, Bob (2004). Chronicles: Volume One. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2815-4.

- "Dylan in the Madhouse". BBC TV. October 14, 2007. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan". AllMusic.com. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- Escott, Colin (2010). The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964 (booklet). Bob Dylan. New York: Columbia Records.

- Flanagan, Bill (May 29, 1991). "Dylan Catalog Revisited". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- Gill, Andy (1999). Classic Bob Dylan: My Back Pages. Carlton. ISBN 1-85868-599-0.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "Ballad in Plain D: An introduction to the Bob Dylan era" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Gorodetsky, Eddie (2005). No Direction Home: The Soundtrack—The Bootleg Series Volume 7 (booklet). Bob Dylan. New York: Columbia Records.

- Gray, Michael (2006). The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Continuum International. ISBN 0-8264-6933-7. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- Harris, John, ed. (2000). "Q Dylan: Maximum Bob! The Definitive Celebration of Rock's Ultimate Genius". Q magazine.

- Harvey, Todd (2001). The Formative Dylan: Transmission & Stylistic Influences, 1961–1963. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4115-0.

- Hentoff, Nat (1963). The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (Media notes). Bob Dylan. New York: Columbia Records.

- Heylin, Clinton (1995). Bob Dylan: The Recording Sessions: 1960–1994. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-15067-9. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- Heylin, Clinton (1996). Bob Dylan: A Life In Stolen Moments: Day by Day 1941–1995. Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-7119-5669-3.

- Heylin, Clinton (2000). Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited. Perennial Currents. ISBN 0-06-052569-X. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- Heylin, Clinton (2003). Can You Feel the Silence? Van Morrison: A New Biography. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1-55652-542-7.

- Heylin, Clinton (2009). Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Volume One: 1957–73. Constable. ISBN 978-1-55652-843-9. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- Humphries, Patrick (1991). Oh No! Not Another Bob Dylan Book. Square One Books. ISBN 1-872747-04-3.

- Levy, Joe (ed.) (2005). The Greatest 500 Albums of All Time. Wenner Books. ISBN 1-932958-61-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Miller, Jim (ed.) (1981). The Rolling Stone History of Rock & Roll. Picador. ISBN 0-330-26568-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "The National Recording Registry". The Library of Congress. June 9, 2002. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- Rotolo, Suze (2009). A Freewheelin' Time. Aurum Press. ISBN 978-0-7679-2688-1.

- Scaduto, Anthony (2001). Bob Dylan. Helter Skelter. ISBN 1-900924-23-4.

- Sharp, Johnny (March 1, 2007). "Scrap that recording—it'll become an instant classic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- Shelton, Robert (2003). No Direction Home. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81287-8.

- Sounes, Howard (2001). Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-1686-8.

- Spitz, Bob (1989). Dylan: A Biography. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-30769-7.

- Thompson, Dave (2002). The Music Lover's Guide to Record Collecting. Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-713-7.

- "Three Song Sampler". iTunes. November 14, 2005. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Williams, Richard (1992). Dylan: a man called alias. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-1084-9.

- 1963 albums

- Albums produced by John Hammond (producer)

- Albums produced by Tom Wilson (record producer)

- Bob Dylan albums

- Columbia Records albums

- United States National Recording Registry recordings

- United States National Recording Registry albums