Carnegie Hall

| |

| |

| Address | 881 Seventh Avenue (at 57th Street) New York City United States |

|---|---|

| Public transit | Subway: 57th Street–Seventh Avenue |

| Owner | City of New York |

| Operator | Carnegie Hall Corporation |

| Type | Concert hall |

| Capacity | Stern Auditorium: 2,804 Zankel Hall: 599 Weill Recital Hall: 268 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | April 1891 |

| Architect | William Tuthill |

Carnegie Hall | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

NYC Landmark No. 0278

| |

| Coordinates | 40°45′54″N 73°58′48″W / 40.76500°N 73.98000°WCoordinates: 40°45′54″N 73°58′48″W / 40.76500°N 73.98000°W |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000535 |

| NYCL No. | 0278 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | December 29, 1962[2] |

| Designated NYCL | June 20, 1967 |

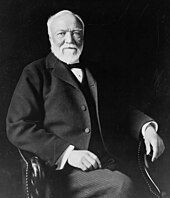

Carnegie Hall (/ˈkɑːrnɪɡi/ KAR-nə-ghee)[3][note 1] is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th and 57th Streets. Designed by architect William Burnet Tuthill and built by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, it is one of the most prestigious venues in the world for both classical music and popular music. Carnegie Hall has its own artistic programming, development, and marketing departments and presents about 250 performances each season. It is also rented out to performing groups.

Carnegie Hall has 3,671 seats, divided among three auditoriums. The largest one is the Stern Auditorium, a five-story auditorium with 2,804 seats. Also part of the complex are the 599-seat Zankel Hall on Seventh Avenue, as well as the 268-seat Joan and Sanford I. Weill Recital Hall on 57th Street. Besides the auditoriums, Carnegie Hall contains offices on its top stories.

Carnegie Hall, originally the Music Hall, was constructed between 1889 and 1891 as a venue shared by the Oratorio Society of New York and the New York Symphony Society. The hall was owned by the Carnegie family until 1925, after which Robert E. Simon and then his son, Robert E. Simon, Jr., became owner. Carnegie Hall was proposed for demolition in the 1950s in advance of the New York Philharmonic relocating to Lincoln Center in 1962. Though Carnegie Hall is designated a National Historic Landmark and protected by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, it has not had a resident company since the New York Philharmonic moved out. Carnegie Hall was renovated multiple times throughout its history, including in the 1940s and 1980s.

Site[]

Carnegie Hall is on the east side of Seventh Avenue between 56th Street and 57th Street, two blocks south of Central Park, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City.[5] The site covers 27,618 square feet (2,565.8 m2). Its lot is 200 feet (61 m) wide, covering the entire width of the block between 56th Street to the south and 57th Street to the north, and extends 150 feet (46 m) eastward from Seventh Avenue.[6]

Carnegie Hall shares the city block with the Carnegie Hall Tower, Russian Tea Room, and Metropolitan Tower to the east. It is cater-corner from the Osborne Apartments. It also faces the Rodin Studios and 888 Seventh Avenue to the west; Alwyn Court, the Louis H. Chalif Normal School of Dancing, and One57 to the north; the Park Central Hotel to the southwest; and the CitySpire Center to the southeast.[5] Right outside the hall is an entrance to the New York City Subway's 57th Street–Seventh Avenue station, served by the N, Q, R, and W trains.[7]

Carnegie Hall is part of an artistic hub that developed around the two blocks of West 57th Street from Sixth Avenue west to Broadway during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its opening in 1891 directly contributed to the development of the hub.[8][9][10] The area contains several buildings constructed as residences for artists and musicians, such as 130 and 140 West 57th Street, the Osborne Apartments, and the Rodin Studios. In addition, the area contained the headquarters of organizations such as the American Fine Arts Society, the Lotos Club, and the American Society of Civil Engineers.[11]

Architecture and venues[]

Carnegie Hall was designed by William Tuthill along with Richard Morris Hunt and Adler & Sullivan.[12][13] While the 34-year-old Tuthill was relatively unknown as an architect, he was an amateur cellist and a singer, which may have led to him getting the commission.[12] Dankmar Adler of Adler & Sullivan, on the other hand, was an experienced designer of music halls and theaters; he served as the acoustical consultant.[12][14] Carnegie Hall was constructed with heavy masonry bearing walls, as lighter structural steel framework was not widely used when the building was completed.[15] The building was designed in a modified Italian Renaissance style.[16][17][18]

Carnegie Hall is composed of three structures arranged in an "L" shape; each structure contains one of the hall's performance spaces. The original building, which houses the Isaac Stern Auditorium, is an eight-story rectangular building at the corner of Seventh Avenue and 57th Street. The 16-story eastern wing contains the Weill Recital Hall and is located along 57th Street. The 13-story southern wing, at Seventh Avenue and 56th Street, contains Zankel Hall. Except at the eighth floor, all three structures have floor levels at different heights.[19]

Facade[]

Carnegie Hall was designed from the outset with a facade of Roman brick.[16][20] The facade was decorated with a large amount of Renaissance details. Most of the exterior walls are covered in reddish brown brick, though decorative elements such as band courses, pilasters, and arches are made of terracotta.[16][17] As originally designed, the terracotta and brick were both brown, and the pitched roof was made of corrugated black tile,[17] but this was later replaced with the eighth floor.[19]

The original section of the building is divided into three horizontal sections. The lowest section of the building comprises the first floor and the first-floor mezzanine, above which is a heavy cornice with modillions. The main entrance of Carnegie Hall is placed in what was originally the center of the primary facade on 57th Street. It consists of an arcade with five large arches, originally separated by granite pilasters.[17][21] An entablature, with the words "Music Hall Founded by Andrew Carnegie", runs across the loggia at the springing of the arches. The center three arches lead directly to the Stern Auditorium's lobby, while the two outer arches lead to staircases to upper floors. On either side of the main entrance are smaller doorways (one on the west and two on the east), topped by blank panels at the mezzanine. There are five similar doorways on Seventh Avenue.[21] The original backstage entrance is on 161 West 56th Street.[22]

On the third and fourth floors, above the main entrance, is a two-and-a-half story arcade on 57th Street with five round-headed arches. A balcony with a balustrade is carried on console brackets in front of this arcade.[21] Each arch has a horizontal terracotta transom bar above the third floor; two third-floor windows separated by a Corinthian column; and two fourth-floor windows separated by a pilaster. A broad terracotta frieze runs above the fourth floor, at the springing of the arches.[17][21] To either side of the arcade, there are two tall round-arched windows on the second floor; those on the east flank a blind arch.[21] There are pairs of pilasters on the fourth-floor mezzanine, above which is a string course. The Seventh Avenue facade is similar in design, but instead of window openings, there are blind openings filled with brick.[17][21] Additionally, the arcade at the center of the Seventh Avenue facade has four arches instead of five.[17]

The sixth floor, at the center of the 57th Street facade, contains five square openings, each with a pair of round-arched windows. On either side of these five openings, there are round-arched windows, arranged as in a shallow loggia.[17][21] There are four arched windows on the eastern portion of the sixth floor, as well as two arches on the west portion, which flank a blind arch.[21] A frieze and cornice run above this floor.[17] The seventh floor was originally a mansard roof.[18] As part of an 1890s alteration, the mansard was replaced with a vertical wall resembling a continuous arcade. The seventh floor is topped by balustrades with decorated columns. The flat roof was converted into a roof garden with kitchen and service rooms.[23][24] Carnegie Hall was also extended to the corner of Seventh Avenue and 56th Street, where a 13-story addition was designed in a similar style as the original building. The top of this addition contains a main dome, as well as smaller domes at its four corners.[24]

Venues[]

Main Hall (Stern Auditorium/Perelman Stage)[]

The Stern Auditorium is six stories high with 2,804 seats on five levels.[25] Originally known as the main auditorium, it was renamed after violinist Isaac Stern in 1997 to recognize his efforts to save the hall from demolition in the 1960s.[26] The main auditorium was originally planned to fit 3,300 guests, including two tiers of boxes, two balconies, and a parquet seating 1,200.[13][27] The main hall was home to the performances of the New York Philharmonic from 1892 until 1962.

Its entrance is through the Box Office Lobby on 57th Street near Seventh Avenue.[28] When planned in 1889, this entrance was designed with a marble and mosaic vestibule measuring 25 feet (7.6 m) high and 70 feet (21 m) long.[27][13] The entrance lobby is three stories high and had an organ loft at the top, which was converted into a lounge area by the mid-20th century.[19] The lobby ceiling was designed as a barrel vault, containing soffits with heavy coffers and cross-arches, and was painted white with gold decorations. At either end of the barrel vault were lunettes. The walls were painted salmon and had pairs of gray-marble pilasters supporting an entablature. The cross-arches had decorated cream-colored tympana.[21] The lobby was originally several feet above street level, but it was lowered to street level in the 1980s.[29][30] The rebuilt lobby contains geometric decorations evocative by the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, as well as Corinthian-style capitals with lighting fixtures.[31][32] The design also includes ticket windows on the south wall of the lobby. Past that, stairs on either side lead to the auditorium's parquet level; previously, stairs continued straight from the lobby to the parquet level.[29]

All but the top level can be reached by elevator; the top balcony is 137 steps above parquet level.[33] The lowest level is the parquet level, which has twenty-five full rows of thirty-eight seats and four partial rows at stage level, for a total of 1,021 seats.[34] The parquet was designed with eleven exits to a corridor that entirely surrounded it; the corridor, in turn, led to the main entrance vestibule on 57th Street.[20] The first and second tiers consist of sixty-five boxes; the first tier has 264 seats, eight per box, and the second tier has 238 seats, six to eight per box.[34] As designed, the first tier of boxes was entirely open, while the second tier was partially enclosed, with open boxes on either end.[20] The third tier above the parquet is the Dress Circle, seating 444 in six rows; the first two rows form an almost-complete semicircle. The fourth and the highest tier, the balcony, seats 837. Although seats with obstructed views exist throughout the auditorium, only the Dress Circle level has structural columns.[34] An elliptic arch rises from the Dress Circle level; along with a corresponding arch at the rear of the auditorium, it supports the ceiling.[21]

The Ronald O. Perelman Stage is 42 feet (13 m) deep.[34] It was originally designed with six tiers that could be raised and lowered hydraulically.[27] The walls around the stage contain pilasters. The ceiling above the stage was designed as an ellipse, and the soffits of the ceiling were originally outfitted with lights.[21] Originally, there were no stage wings; the backstage entrance from 56th Street led directly to a small landing just below the stage, while the dressing room was above the stage. During a 1980s renovation, a stage wing, orchestra room, and dressing rooms were added and the access to the stage was reconfigured.[22]

Zankel Hall[]

Zankel Hall, on the Seventh Avenue side of the building, is named after Judy and Arthur Zankel, who funded a renovation of the venue.[35][36] Originally called simply Recital Hall, this was the first auditorium to open to the public in April 1891. It had a balcony, elevated side galleries, a beamed ceiling, and removable seats.[37] The space was an oratorio hall capable of accommodating over 1,000 people, and it could double as a banquet hall.[20][37] There was a full kitchen service,[37] as well as a dais on either side.[13][27] The space was originally designed with dimensions of 90 by 96 feet (27 by 29 m).[13] Following renovations made in 1896, it was renamed Carnegie Lyceum. It was leased to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in 1896, converted into the Carnegie Hall Cinema in May 1961.[35] The venue became a performance space in 1997.[35][38]

The completely reconstructed Zankel Hall opened in September 2003.[39] It is accessed from Seventh Avenue,[38] where there is a marquee.[40][41] Two escalators lead to the balcony and orchestra levels.[38] The venue was originally planned with 640 seats and can be arranged with either a center stage, an end stage, or no stage.[40][42] This is accomplished through the division of the floor into nine sections, each 45 feet (14 m) wide with a separate lift underneath.[43] The 599 seats in Zankel Hall are arranged in two levels. The parterre level seats a total of 463 and the mezzanine level seats 136. Each level has a number of seats which are situated along the side walls, perpendicular to the stage. These seats are designated as boxes; there are 54 seats in six boxes on the parterre level and 48 seats in four boxes on the mezzanine level. The boxes on the parterre level are raised above the level of the stage. Zankel Hall is accessible and its stage is 44 feet wide and 25 feet deep.[44]

Due to the limited space available on the land lot, the construction of Zankel Hall required excavating 8,000 cubic feet (230 m3) of additional basement space, at some points only 10 feet (3.0 m) under the Stern Auditorium's parquet level.[35] The excavations descended up to 22 feet (6.7 m) below the original space's floor and came as close as 9 feet (2.7 m) to the adjacent subway tunnel.[38] This also required the removal of twelve cast-iron columns holding up the Main Hall. In its place, a temporary framework of steel pipe columns, supporting I-beam girders and thick Neoprene insulation pads, was installed.[35][43] JaffeHolden Acoustics installed the soundproofing, which filters out noise from both the street and the subway.[45] An elliptical concrete wall, measuring 12 inches (300 mm) wide, surrounds Zankel Hall and supports the Stern Auditorium. The elliptical enclosure measures 114 feet (35 m) long and 76 feet (23 m) wide.[46] The walls are sloped at a 7-degree angle and contain sycamore paneling. The lighting and sound equipment is mounted from twenty-one trusses.[41]

Weill Recital Hall[]

The Joan and Sanford I. Weill Recital Hall is named after Sanford I. Weill, a former chairman of Carnegie Hall's board, as well as his wife Joan.[47] This auditorium, in use since the hall opened in 1891, was originally called Chamber Music Hall[48] and was placed in the "lateral building" east of the main hall.[20] The space later became the Carnegie Chamber Music Hall. The name was changed to Carnegie Recital Hall in the late 1940s, and the venue finally became Joan and Sanford I. Weill Recital Hall in 1987.[48]

The recital hall is served by its own lobby, which contains a pale color palette with red geometric metalwork. Prior to a 1980s renovation, it shared a lobby with the main auditorium.[49] The Weill Recital Hall is the smallest of the three performance spaces, with a total of 268 seats. The Orchestra level contains fourteen rows of fourteen seats, a total of 196, and the Balcony level contains 72 seats in five rows.[50]

Other facilities[]

A boiler room was placed under the sidewalk on Seventh Avenue.[20] A small electric generation plant for 5,300 lamps was also planned.[13] At the ground level of the main hall, stores were installed in the 1940s.[51] The storefronts, as well as a restaurant at the corner of 57th Street and Seventh Avenue, were removed in a 1980s renovation.[49][52] Originally, there was a 150-seat dining room on the ground level below the Chamber Music Hall. Above the dining room, but below the venue itself, were parlors, cloak rooms, and restrooms.[20]

Above the Chamber Music Hall was a large chapter-room, a meeting room, a gymnasium, and twelve short-term "lodge rooms" in the roof.[20] The 56th Street side of Carnegie Hall was designed with rooms for the choruses, soloists, and conductors, as well as offices and lodge rooms. On the roof of the 56th Street section were janitors' apartments. Three elevators, two on the 57th Street side and one on the 56th Street side, originally served the building.[20] The addition at the corner of 56th Street and Seventh Avenue was arranged with offices, studios, and private music rooms.[23][24]

The eighth floor of the main hall, which contained studios, was installed after the complex was completed.[51] The spaces were purpose-designed for artistic work, with very high ceilings, skylights and large windows for natural light. In 2007 the Carnegie Hall Corporation announced plans to evict the 33 remaining studio residents, some of whom had been in the building since the 1950s, including celebrity portrait photographer Editta Sherman and fashion photographer Bill Cunningham. The organization's research showed that Andrew Carnegie had always considered the spaces as a source of income to support the hall and its activities. After 1999, the space was re-purposed for music education and corporate offices.[53][54]

The building also contains the Carnegie Hall Archives, established in 1986, and the Rose Museum, which opened in 1991. The Rose Museum is east of the first balcony of the Stern Auditorium and has dark makore and light anigre paneling with brass edges, as well as columns with brass capitals, supporting a coffered ceiling. The Rose Museum space is separated from two adjacent rooms by sliding panels.[55]

History[]

The idea for what is now Carnegie Hall came from Leopold Damrosch, the conductor of Oratorio Society of New York and the New York Symphony Society.[12] Though Leopold Damrosch died in 1885,[56] his son Walter Johannes Damrosch traveled to Germany two years later to study music. It was there that the younger Damrosch was introduced to the businessman Andrew Carnegie, who served on the board of not only the Oratorio Society but also the New York Symphony.[12][57] Carnegie was originally uninterested in funding a music hall in Manhattan, but he agreed to give $2 million after discussions with Damrosch.[12][51] According to architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern, the Music Hall was "unique in that it was free of commercial sponsorship and exclusively dedicated to musical performance".[12]

Development and opening[]

In early March 1889, Morris Reno, director of the Oratorio and New York Symphony societies acquired nine lots on and around the southeast corner of Seventh Avenue and 57th Street.[58][59] William Tuthill had been hired to design a "great music hall" on the site.[58][60] The Music Hall, as it was called, would be a five-story brick and limestone building, containing a 3,000-seat main hall with and several smaller rooms for rehearsals, lectures, concerts, and art exhibitions.[58][60] The New York Times said "The location for the music hall is perhaps rather far uptown, but it is easily accessible from the 'living' part of the city."[58] The Music Hall Company was incorporated on March 27, 1889, with Carnegie, Damrosch, Reno, Tuthill, and as trustees.[61][62] Originally, the Music Hall Company intended to limit its capital stock to $300,000, but this was increased before the end of 1889 to $600,000, of which Carnegie held five-sixths. The cost of the building was then projected to be $1.1 million, including the land.[63]

By July 1889, Carnegie's company had acquired additional land, with frontage of 175 feet (53 m) on 57th Street. The architectural drawings were nearly completed and excavations for the music hall had been completed.[13] The Henry Elias Brewery owned the corner of Seventh Avenue and 56th Street and originally would not sell the land, as its proprietor believed the site had a good water source.[37] Plans for the Music Hall were filed in November 1889.[14] Andrew Carnegie's wife Louise laid the cornerstone for the Music Hall on May 13, 1890.[64][65][66] Isaac A. Hopper and Company was the contractor in charge of building the Music Hall.[67][68] The Real Estate Record and Guide praised the building's design as "harmonious, animated without restlessness, and quiet without dullness."[17] In February 1891, Damrosch announced that he had created a subscription fund for a "permanent orchestra" that would perform mainly in the new Music Hall.[69][70]

The Recital Hall was opened the following month for the recitals of the New York Oratorio Society.[71] It was around this time that tickets for the official opening of the Music Hall were being sold.[72] The oratorio hall in the basement opened on April 1, 1891,[73][37] with a performance by Franz Rummel.[74] The Music Hall officially opened on May 5, 1891, with a rendition of the Old 100th hymn, a speech by Episcopal bishop Henry C. Potter, and a concert conducted by Walter Damrosch and Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.[21][75] During the performance, Tuthill looked at the crowds on the auditorium's top tiers and reportedly left the hall to consult his drawings. He was uncertain that the supporting columns would withstand the weight of the crowd in attendance, but the dimensions turned out to be sufficient to support the weight of the crowd.[12][76] Tchaikovsky, for his part, considered the auditorium "unusually impressive and grand" when "illuminated and filled with an audience".[12][77] The New York Herald praised the auditorium's acoustical qualities, saying "each note was heard".[12][78]

Late 19th to mid-20th century[]

1890s[]

In May 1892, the stockholders of the Music Hall Company of New York held a meeting to discuss the expansion of the Music Hall. The brewery at Seventh Avenue and 56th Street had been purchased about three months previously, but the ground floor of the brewery had a liquor shop whose lease did not expire for a year. The Music Hall Company also discussed enlarging the main auditorium's stage so it could accommodate operas.[79] Plans for the extension of the Music Hall were formulated by that September,[80] but Morris Reno said the stage could not be modified until at least early 1893.[81] The Music Hall Company filed plans for alterations in December 1892. The plans called a tower of about 240 feet (73 m) at the corner of Seventh Avenue and 56th Street. In addition, the original building's mansard roof would become a flat roof, and the seventh story would be converted into a full story.[23][24]

In 1896, the American Academy of Dramatic Arts moved into the basement recital hall (later Zankel Hall). The academy leased the basement recital hall for the next fifty-four years.[37] In 1898, the Music Hall was renamed Carnegie Hall for its main benefactor.[51] According to Carnegie Hall archivist , the renaming occurred "so that it shouldn't be confused by European artists with a vulgar music hall".[82]

1900s to 1940s[]

The hall was owned by the Carnegie family until 1925, when Carnegie's widow sold it to a real estate developer, Robert E. Simon.[83] The sale included a clause that mandated Carnegie Hall continue to operate as a performance venue for at least five years or another venue be erected on the site. This was to prevent the site from being redeveloped immediately with a commercial or residential development.[84][85] Under Simon's leadership, a new organ was installed in Carnegie Hall in 1929.[86][87]

Robert Simon died in 1935.[88] Murray Weisman succeeded Simon as president of Carnegie Hall's board of directors, while the late owner's son Robert E. Simon Jr. became the vice president.[89][90] A bust of the senior Simon was installed in the lobby in 1936.[91][92]

The main hall was modified around 1946 during filming for the movie Carnegie Hall. A hole was made in the stage's ceiling to allow the installation of ventilation and lights for the film. Canvas panels and curtains were placed over the hole, but the acoustics in the front rows became noticeably different.[93] In 1947, Robert E. Simon Jr. undertook renovations of the hall. The work was carried out by New York firm Kahn and Jacobs.[94][95]

Preservation[]

By the 1950s, changes in the music business prompted Simon to sell the hall. In April 1955, Simon negotiated with the New York Philharmonic, which booked a majority of the hall's concert dates each year.[96] The orchestra planned to move to Lincoln Center, then in the early stages of planning.[97] Simon notified the Philharmonic that he would terminate the lease by 1959 if it did not purchase Carnegie Hall.[98] In mid-1955, longtime employee John Totten organized a fundraising drive to prevent the destruction of Carnegie Hall.[99] Meanwhile, the Academy of Dramatic Arts had moved out of the basement recital hall in 1954. The Academy's former space was rented for the time being to other tenants.[37][43]

Simon sold the entire stock of Carnegie Hall Inc., the venue's legal owner, to commercial developer Glickman Corporation in July 1956 for $5 million.[97][100] With the Philharmonic on the move to Lincoln Center, the building was slated for demolition to make way for a 44-story skyscraper designed by Pomerance and Breines. The replacement tower would have had a red facade and would have been constructed on stilts, with art exhibits and other cultural facilities at the base.[101][102][103] However, Glickman was unable to come up with the $22 million construction budget for the skyscraper.[97] This, combined with delays in Lincoln Center's construction, prompted Glickman to decline an option to buy the building itself in July 1958.[104][105]

Meanwhile, soon after the sale, Simon started planning the hall's preservation, approaching some of the hall's artist residents. Violinist Isaac Stern enlisted his friends Jacob M. and Alice Kaplan, as well as J. M. Kaplan Fund administrator Raymond S. Rubinow, for assistance in saving the hall.[97] In 1959, two hundred residents of Carnegie Hall's studios were asked if they wanted to buy the building.[106] Stern, the Kaplans, and Rubinow ultimately decided that the best move would be for the city government to become involved.[97] The move gained support from mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr., who created a taskforce to save Carnegie Hall in early 1960,[107][108] but Simon and his co-owners still filed eviction notices against some studio tenants.[109] The same year, special legislation was passed, allowing the city government to buy the site from Simon for $5 million. Simon used the money to establish Reston, Virginia.[110] The city then leased the hall to the nonprofit Carnegie Hall Corporation, which was created to run the venue.[97]

A minor renovation of Carnegie Hall's interior, as well as a steam-cleaning of the facade, took place in mid-1960.[111] The basement recital hall became a movie theater called the Carnegie Playhouse. A screen was installed at the front of the former stage, while the balconies and side galleries were sealed.[37][43] The Carnegie Hall Cinema opened in May 1961 with a showing of the film White Nights by Luchino Visconti.[112][113] Carnegie Hall was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1962.[2][114][115] The landmark status was certified in 1964 and a National Historic Landmark plaque was placed on the building.[116][117] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission also designated Carnegie Hall as a city landmark in September 1967.[18][118]

Deterioration and renovation[]

For fifteen years, the Carnegie Hall Corporation paid the New York City government $183,600 in cash, Afterward, the corporation started paying the city through benefit concerts and outreach programs. Carnegie Hall became a more popular destination in the 1960s and 1970s, in part because of complaints over acoustics in the new Philharmonic Hall.[119][73] The deficiencies with Carnegie Hall's facilities became more prominent after the latter's renovation.[119] Carnegie Hall began to deteriorate due to neglect, and the corporation faced fiscal deficits. By the mid-1970s, the venue suffered from burst pipes and falling sections of the ceiling, and there were large holes in the balconies that patrons could put their feet through. At the same time, operating costs had increased from $3.5 million in 1977 to $10.3 million in 1984, and the deficits had also risen accordingly.[52] Carnegie Hall's equipment included a rundown air-conditioning system that did not work in the summer.[120]

In 1977, the Carnegie Hall Corporation decided to stop accepting residents for its upper-story studios, but existing residents were allowed to continue living there. The studios were instead offered for commercial use only.[121] In 1979, the board of Carnegie Hall Corporation hired James Stewart Polshek and his firm, Polshek Partnership, to create a master plan for Carnegie Hall's renovation and expansion. Polshek found that Carnegie Hall's electrical systems, exits, fire alarms, and other systems were not up to modern building codes.[119] The next year, the Carnegie Hall Corporation and the New York City government signed a memorandum of understanding, which would permit the development of the adjacent site to the east, a parking lot.[31][122][123] In 1981, the federal government gave Carnegie Hall $1.8 million for the renovation; the city and Astor Foundation had previously given $450,000.[124]

1980s[]

The first renovations started in February 1982 with the restoration and reconstruction of the recital hall and studio entrance.[119] The lobby was lowered to street level, the box office was relocated to behind the main auditorium, and two archways were added to the 57th Street facade.[31][125] A new lobby and dedicated elevator for the recital hall was also created.[49][126] The Carnegie Hall Corporation was also looking to develop a vacant lot immediately east of Carnegie Hall.[126][127] The renovation was complicated by the fact that some parts of the original plans had been lost.[31][119] A controversy also emerged when the Carnegie Hall Corporation started evicting longtime tenants of the hall's upper-story studios, particularly those who refused to pay steeply increased rents.[128][129] The first phase of the renovation was completed in September 1983 for $20 million.[49]

The corporation announced in May 1985 that the main hall and recital hall would be closed for several months. The corporation also started a fundraising drive to raise the $50 million needed to fund the renovation; more than half of the funding had already been raised at the time. A new structure designed by César Pelli, later to become the Carnegie Hall Tower, was planned for the lot immediately east of Carnegie Hall.[52][130][131] Some of the work had already been completed with the earlier donations, including reconstruction of the elevators and recital hall lobby; upgrades to mechanical systems, such as air-conditioning and elevators; and conversion of the old chapter room into the Kaplan Space, a multipurpose room.[130] Further upgrades, which required the main and recital halls' closure, included upgrades to both halls, the lobby, the facade, backstage areas, and offices. The lobby was lowered to street level and doubled in size.[30][132]

The Landmarks Preservation Commission approved the proposed renovation in July 1985.[31][133] Renovation work began afterward. The project was complicated by the need to schedule construction around performances, the lack of a freight elevator, and the requirement that materials be replaced with close or exact replacements.[134] In April 1986, Carnegie officials announced their intent to sublease the vacant lot to Rockrose Development for the construction of Carnegie Hall Tower.[135][136][137] The following month, the hall closed completely for a seven-month renovation.[138][139] That November, Carnegie Hall announced it would rename the recital hall after Joan and Sanford I. Weill, who not only were major donors to the renovation but also enlisted other donors to fund the project.[140]

The main hall (including the Stern Auditorium) was reopened on December 15, 1986, with a gala featuring Zubin Mehta, Frank Sinatra, Vladimir Horowitz, and the New York Philharmonic.[141][142] The Kaplan Rehearsal Space was also created in 1986,[143] and the Weill Recital Hall opened in January 1987.[144][145] A month after the main hall reopened, New York Times music critic Bernard Holland criticized its acoustics, saying: "The acoustics of this magnificent space are not the same."[31][146] Several noise-absorbing panels were installed in the hall the following year.[31][147] However, complaints about the main hall continued for several years.[31] Critics alleged there was concrete underneath the stage, but Carnegie Hall officials denied the allegations. Isaac Stern offered to disassemble the stage on the condition that the critics pay for the repairs if no concrete was found.[148] Polshek Partners won the American Institute of Architects' Honor Award in 1988 for its renovation of the hall.[55]

1990s and early 2000s[]

During the late 1980s, Carnegie Hall had begun collecting items for the opening of a museum in the under-construction Carnegie Hall Tower.[149][150] The Rose Museum was founded in April 1991,[151][152] with its own entrance at 154 West 57th Street.[153] The East Room and Club Room (later renamed Rohatyn Room and Shorin Club Room, respectively[154]) were created the same year. Though the East and Club rooms were in Carnegie Hall Tower, they were connected to the original Carnegie Hall.[155] This represented the first new space added to Carnegie Hall since the studios were added in the late 1890s.[156] At the parquet level, Cafe Carnegie was also renovated.[55]

The stage of the main hall had begun to warp by the early 1990s, and officials disassembled the stage in 1995, where they discovered a slab of concrete.[31][148] John L. Tishman, president of Tishman Realty & Construction, which had renovated the stage in 1986, alleged that the concrete was there before the renovation.[31][157] The concrete was removed in mid-1995 while Carnegie Hall was closed for the summer;[158] soon afterward, critics described a noticeable change in the acoustics.[159]

In the basement, the Carnegie Hall Cinema operated separately from the rest of Carnegie Hall until 1997, when the hall's management closed the cinema, along with two shops on Seventh Avenue. In late 1998, Carnegie Hall announced that it would turn the basement recital hall into another performance venue, designed by Polshek Associates. The project was to cost $50 million; the high cost was attributed to the fact that the work would require excavations under the basement while concerts and other events were ongoing.[160] In recognition of a $10 million grant from Arthur and Judy Zankel, the new space was renamed after the Zankels in January 1999; the auditorium proper was named after Judith Arron, who donated $5 million.[40] Construction took place without disrupting performances or the nearby subway tunnel.[41] Zankel Hall had been planned to open in early 2003, but the opening date was postponed due to the city's economic difficulties after the September 11 attacks in 2001.[38][161] The excavations also raised the budget to $69 million.[161]

21st century[]

In June 2003, tentative plans were made for the Philharmonic to return to Carnegie Hall beginning in 2006, and for the orchestra to merge its business operations with those of the venue. However, the two groups abandoned these plans later that year.[162] Zankel Hall opened in September 2003.[38][163] Music critic Anthony Tommasini praised Zankel Hall's flexibility, though he said "the builders did not quite succeed in insulating the auditorium from the sounds of passing trains".[164] Architecturally, the space was described by critic Herbert Muschamp as "a luxury version of a black-box theater, the hall has the feel of a broadcasting studio, which it partly is".[43][165] Though Zankel Hall's large capacity was highly publicized, it was only reconfigured once in its first two and a half years of operation.[166] The Stern Auditorium's stage was renamed in March 2006 after Ronald Perelman, who had donated $20 million to Carnegie Hall.[167][168]

Carnegie Hall Corporation announced in 2007 that it would evict all the remaining tenants of its upper-story studios so the corporation could convert the space into offices.[169][170] The last tenant had moved out by 2010.[171] In 2014, Carnegie Hall opened its Judith and Burton Resnick Education Wing, which houses 24 music rooms, one of which is large enough to hold an orchestra or a chorus. The $230 million project was funded with gifts from Joan and Sanford I. Weill and the Weill Family Fund, Judith and Burton Resnick, Lily Safra and other donors, as well as $52.2 million from the city, $11 million from the state and $56.5 million from bonds issued through the Trust for Cultural Resources of the City of New York.[172]

Carnegie Hall closed temporarily in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. In June 2021, Carnegie Hall announced it would reopen that October.[173][174]

Events and performances[]

Most of the greatest performers of classical music since Carnegie Hall's opening have performed in the Main Hall, and its lobbies are adorned with signed portraits and memorabilia. The NBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Arturo Toscanini, frequently recorded in the Main Hall for RCA Victor. On November 14, 1943, the 25-year old Leonard Bernstein had his major conducting debut when he had to substitute for a suddenly ill Bruno Walter in a concert that was broadcast by CBS,[175] making him instantly famous. In late 1950, the orchestra's weekly broadcast concerts were moved there until the orchestra disbanded in 1954. Several of the concerts were televised by NBC, preserved on kinescopes, and have been released on home video.[citation needed]

Many legendary jazz and popular music performers have also given memorable performances at Carnegie Hall including Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller, Billie Holiday, Billy Eckstine, the Dave Brubeck Quartet, Keith Jarrett, Judy Garland, Harry Belafonte, Charles Aznavour, Simon and Garfunkel, Paul Robeson, Nina Simone, Shirley Bassey, James Taylor, and Stevie Ray Vaughan, all of whom made celebrated live recordings of their concerts there.[citation needed]

The hall has also been the site of many famous lectures, including the Tuskegee Institute Silver Anniversary Lecture by Booker T. Washington, and the last public lecture by Mark Twain, both in 1906.[citation needed]

Sissieretta Jones became the first African-American to sing at Carnegie Hall on June 15, 1892.[176][177] The Benny Goodman Orchestra gave a sold-out swing and jazz concert January 16, 1938. The bill also featured, among other guest performers, Count Basie and members of Duke Ellington's orchestra.[citation needed]

Rock and roll music first came to Carnegie Hall when Bill Haley & His Comets appeared in a variety benefit concert on May 6, 1955.[178] Rock acts were not regularly booked at the Hall however, until February 12, 1964, when The Beatles performed two shows[179] during their historic first trip to the United States.[180] Promoter Sid Bernstein convinced Carnegie officials that allowing a Beatles concert at the venue "would further international understanding" between the United States and Great Britain.[181] Two concerts were performed October 17, 1969.[182] Since then numerous rock, blues, jazz and country performers have appeared at the hall every season.[183] Some performers and bands had contracts that specified decibel limits for performances, an attempt to discourage rock performances at Carnegie Hall.[52] Jethro Tull released the tapes recorded on its presentation in a 1970 Benefit concert, in the 2010 re-release of the Stand Up album. Ike & Tina Turner performed a concert April 1, 1971, which resulted in their album What You Hear is What You Get. The Beach Boys played concerts in 1971 and 1972, and two songs from the show appeared on their Endless Harmony Soundtrack. Chicago recorded its 4-LP box set Chicago at Carnegie Hall in 1971.

European folk dance music first came to Carnegie Hall when concert of Yugoslav National Folk Ballet Tanec was performed on January 27, 1956. Ensemble Tanec was the first dance company from Yugoslavia to perform in America. The company performed folk dances from Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia and Albania.[184]

The 2015–2016 season celebrated the hall's 125th anniversary and the launch of an unprecedented commissioning project of at least 125 new works with 'Fifty for the Future" coming from Kronos (25 by female composers and 25 by male composers).[citation needed]

Management and operations[]

As of 2021, the Executive and Artistic Director of Carnegie Hall is Sir Clive Gillinson, formerly managing director of the London Symphony Orchestra.[174] Gillinson started serving in that position in 2005.[185][186]

The hall's operating budget for the 2008–2009 season was $84 million. For 2007–2008, operating costs exceeded revenues from operations by $40.2 million. With funding from donors, investment income and government grants, the hall ended that season with $1.9 million more in total revenues than total costs.

Carnegie Hall Archives[]

It emerged in 1986 that Carnegie Hall had never consistently maintained an archive. Without a central repository, a significant portion of Carnegie Hall's documented history had been dispersed. In preparation for the celebration of Carnegie Hall's centennial in 1991, the management established the Carnegie Hall Archives that year.[187][188] The historical archival collections were renamed the Carnegie Hall Susan W. Rose Archives in 2021, after a longtime trustee and donor to the Archives and Rose Museum.[189]

Folklore[]

Famous joke[]

Rumor is that a pedestrian on Fifty-seventh Street, Manhattan, stopped Jascha Heifetz and inquired, "Could you tell me how to get to Carnegie Hall?" "Yes," said Heifetz. "Practice!"[190]

This joke has become part of the folklore of the hall, but its origins remain a mystery.[191] Although described in 1961 as an "ancient wheeze", its earliest known appearances in print date from 1955.[191][192] Attributions to Jack Benny are mistaken; it is uncertain if he ever used the joke.[193] Alternatives to violinist Jascha Heifetz as the second party include an unnamed beatnik, bopper, or "absent-minded maestro", as well as pianist Arthur Rubinstein and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie.[191][192][193][194] Carnegie Hall archivist Gino Francesconi favors a version told by the wife of violinist Mischa Elman, in which her husband makes the quip when approached by tourists while leaving the hall's backstage entrance after an unsatisfactory rehearsal. The joke is so well known it is often reduced to a riddle with no framing story.[191] According to The Washington Post, the joke "shows how firmly the building [...] has lodged itself in American folklore".[195]

Other lore[]

Other stories have been attributed to the folklore of Carnegie Hall.[195][196] One such story concerns a performance on the unusually hot day of October 27, 1917,[195] when Heifetz made his American debut in Carnegie Hall.[197] After Heifetz had been playing for a while, fellow violinist Mischa Elman mopped his head and asked if it was hot in there. Pianist Leopold Godowsky, in the next seat, replied, "Not for pianists."[195][196]

While the Elman/Godowsky anecdote was confirmed to be true, other accounts about Carnegie Hall may have been apocryphal in nature.[196] One such story involved violinist Fritz Kreisler and pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff, who were supposedly performing a Beethoven sonata when Kreisler lost track of what he was playing. After a few minutes of improvisation, Kreisler allegedly asked "For God's sake, Sergei, where am I?", to which Rachmaninoff was said to have responded, "In Carnegie Hall."[195][198]

See also[]

- Alliance for the Arts, advocacy organization for Carnegie Hall

- Carnegie Hall – a 1947 film featuring the venue as the setting for the plot and numerous performances

- Other venues named Carnegie Hall:

- Carnegie Hall, Inc., in Lewisburg, West Virginia

- Carnegie Music Hall at the main site of the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh and the main branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

- Carnegie Music Hall at Carnegie Free Library of Braddock in Braddock, Pennsylvania

- Carnegie Music Hall at Carnegie Library of Homestead in Homestead, Pennsylvania

- Carnegie Music Hall at Andrew Carnegie Free Library & Music Hall in Carnegie, Pennsylvania.

- Dunfermline, Andrew Carnegie's hometown, which contains a Carnegie Hall

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References[]

Notes[]

Citations[]

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carnegie Hall". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 9, 2007. Archived from the original on November 6, 2007.

- ^ "American English: Carnegie Hall". Macmillan Dictionary. Retrieved August 27, 2020.; "Carnegie Hall in British English". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "History of the Hall: History FAQ". Carnegie Hall. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "881 7 Avenue, 10019". New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: 57 St 7 Av (N)(Q)(R)(W)". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (May 9, 1999). "Streetscapes /57th Street Between Avenue of the Americas and Seventh Avenue; High and Low Notes of a Block With a Musical Bent". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ "Steinway Hall" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 13, 2001. pp. 6–7. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- ^ "Society House of the American Society of Civil Engineers" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 16, 2008. p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1999). New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age. Monacelli Press. p. 691. ISBN 978-1-58093-027-7. OCLC 40698653.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Carnegie Music Hall.; the Work of Construction Is Expected to Begin Soon" (PDF). The New York Times. July 19, 1889. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Plans for a Big Building Filed: the Music Hall Company Getting Ready to Begin Work--expectations of the Stockholders". New-York Tribune. November 21, 1889. p. 7. ProQuest 573493968.

- ^ "1891 Andrew Carnegie's new Music Hall opens - Carnegie Hall". carnegiehall.org. May 28, 2016. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Carnegie Hall" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 10, 1966. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "The Carnegie Music Hall". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. 46 (1189): 867–868. December 27, 1890 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c National Park Service 1962, p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "The New Music Hall Plans: a Fine Building to Be Erected It Will Be Ready for the World's Fair--architectural Features and Interior Arrangements". New-York Tribune. September 10, 1889. p. 7. ProQuest 573484756.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l "It Stood the Test Well: the First Concert in the New Music Hall. Its Acoustic Properties Found to Be Adequate -- a Russian Composer Warmly Greeted -- Bishop Potter as a Lover of Music". The New York Times. May 6, 1891. p. 5. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 94939305.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kraus, Lucy (August 31, 1986). "The Carnegie Hall of the Future". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "For a Bigger Music Hall: Elaborate Plans of Reconstruction There Will Be High Tower and Other Changes Will Be Made". New-York Tribune. December 28, 1892. p. 7. ProQuest 573728011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Addition to Music Hall; Work Planned That Will Make a Great Improvement. Better Exterior Appearance Promised and Much More Room -- a Lofty Tower of Unique Design -- Garden on the Roof -- New Concert Room and Studios". The New York Times. December 28, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall". National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. October 15, 1966. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ "The A to Z of Carnegie Hall: S is for Stern". Carnegie Hall. September 23, 2013. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Men and Things". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. 44 (1114): 1017. July 20, 1889 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Parking & Directions". Carnegie Hall. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carnegie Hall's New Lobby" (PDF). Oculus. 48 (7): 3–11. March 1986.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shepard, Joan (December 15, 1986). "Encore for Carnegie Hall". New York Daily News. p. 101. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 732.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (September 8, 1983). "Architecture: Carnegie Hall Restoration, Phase 1". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Information: Accessibility". Carnegie Hall. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Carnegie Hall. "Stern Auditorium-Perelman Stage Rentals". Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Dunlap, David W. (January 30, 2000). "Carnegie Hall Grows the Only Way It Can; Burrowing Into Bedrock, Crews Carve Out a New Auditorium". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Kinneberg, Caroline. "Judy and Arthur Zankel Hall". NYMag.com. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Blumenthal, Ralph (January 3, 1998). "In the Offing, Another Hall In Carnegie's Basement". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "At Carnegie Hall, music goes underground". UPI. September 15, 2003. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (September 12, 2003). "Architecture Review; Zankel Hall, Carnegie's Buried Treasure". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kozinn, Allan (January 12, 1999). "A New Stage And Lineup For Concerts At Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Weathersby, William, Jr. (January 2005). "Zankel Hall, New York City" (PDF). Architectural Record. 193: 157–161.

- ^ Lewis, Julia Einspruch (March 1999). "A new stage for a hallowed hall". Interior Design. 70 (4): 35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 733.

- ^ Carnegie Hall. "Zankel Hall Rental". Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (April 3, 2003). "A New Underground at Carnegie, in More Ways Than One". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (May 5, 2002). "When Expansion Leads to Inner Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Weill Recital Hall". Carnegie Hall. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rockwell, John (January 6, 1987). "Weill Recital Hall Opens at Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Goldberger, Paul (September 8, 1983). "Architecture: Carnegie Hall Restoration, Phase 1". The New York Times. p. C16. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 424782471.

- ^ Carnegie Hall. "Weill Recital Hall". Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d National Park Service 1962, p. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cox, Meg (May 17, 1985). "Fabled Carnegie Hall, Often Close to Death, Will Receive Surgery: But the Challenge to Restorers Of New York Auditorium Is to Avoid Harming It Fabled Carnegie Hall in New York Will Soon Receive Major Surgery". Wall Street Journal. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 135117567.

- ^ Goodman, Wendy (December 30, 2007). "Great Rooms: Bohemia in Midtown". New York. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Pressler, Jessica (October 20, 2008). "Editta Sherman, 96-Year-Old Squatter". New York. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Stephens, Suzanne (March 1992). "Architectural Ethics" (PDF). Architecture: 75.

- ^ "Death of Dr. Damrosch.; Fatal Result of a Brief Illness". The New York Times. February 16, 1885. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ Shanor, Rebecca (1988). The City That Never Was : Two Hundred Years of Fantastic and Fascinating Plans That Might Have Changed the Face of New York City. New York, N.Y., U.S.A: Viking. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-670-80558-7. OCLC 17510109.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "A New Music Hall.; Carnegie Takes Hold of the Project and a Site Is Bought" (PDF). The New York Times. March 15, 1889. p. 4. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "To Build a Music Hall: Plans for a Magnificent Building". New-York Tribune. March 15, 1889. p. 1. ProQuest 573444377.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Out Among the Builders". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. 43 (1097): 392–393. March 23, 1889 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "The New Music Hall Company". The New York Times. March 28, 1889. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Incorporating a Music Hall Company". New-York Tribune. March 28, 1889. p. 1. ProQuest 573489130.

- ^ "Some Fine New Buildings; Grand Edifices Now Going Up in This City. The Carnegie Music Hall, Century, Republican, and Athletic Club Houses, and Lenox Lyceum" (PDF). The New York Times. December 15, 1889. p. 11. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "A New Home for Music". The Sun. May 14, 1890. p. 7. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "A Great Home of Music: Mrs. Carnegie Lays the Cornerstone of the Building Addresses by Morris Reno, E. Francis Hyde and Andrew Carnegie". New-York Tribune. May 14, 1890. p. 7. ProQuest 573539715.

- ^ "The New Music Hall". Architecture and Building: A Journal of Investment and Construction. W. T. Comstock. 12: 234. 1890. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Isaac A. Hopper's Record.; Some Notable Achievements in His Line as a Builder" (PDF). The New York Times. January 1, 1893. p. 9. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "A Busy Life". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. 55 (1399): 7. January 5, 1895 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Damrosch's Liberal Backers". The Evening World. February 6, 1891. p. 4. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Our Permanent Orchestra". The Sun. February 6, 1891. p. 1. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "A New Concert Room". The Sun. March 13, 1891. p. 3. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "To Open the New Music Hall: the Amended Programme--many Eminent Performers". New-York Tribune. March 22, 1891. p. 24. ProQuest 573653596.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 731.

- ^ "Amusements". The New York Times. April 2, 1891. p. 4. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 94850411.

- ^ "The Music Hall Opened". New-York Tribune. May 6, 1891. pp. 1, 7. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (June 29, 1980). "Carnegie Hall, at 90, Is Thinking Young; MUSIC VIEW Carnegie Hall, Approaching 90, Is Thinking Young". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Yoffe, Elkhonon (1986). Tchaikovsky in America : the composer's visit in 1891. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-19-504117-0. OCLC 13498952.

- ^ "Music Crowd in Its New Home". New York Herald. May 6, 1891. p. 7.

- ^ "Changes at the Music Hall: Plans Which May Change the Place Into an Opera House". New-York Tribune. May 12, 1892. p. 7. ProQuest 573781812.

- ^ "A Home for Grand Opera.; Plans for Transforming Music Hall Into an Opera House". The New York Times. September 5, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "No Grand Opera This Season.; the Carnegie Music Hall Stage Cannot Be Rebuilt for It". The New York Times. September 19, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Shepard, Richard F. (May 12, 1988). "Carnegie Hall Marks a Milestone for a Cornerstone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "New Leader Rises in City Real Estate; Carnegie Hall Deal Discloses Robert E. Simon as a Manipulator of Millions". The New York Times. February 1, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall Sold, but Wins 5 Years' Grace: R. E. Simon Buys Historic Music Center, Agreeing to Time Clause Unless New Auditorium Is Built Sooner". The New York Herald, New York Tribune. January 30, 1925. p. 11. ProQuest 1112791299.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall Is About to Be Sold, but Won't Close Yet; Clause in Sale Contract Safeguards Concerts There for the Next Five Years". The New York Times. January 30, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "A New Organ To Be Installed In Carnegie Hall: Preliminary Work for Placing the Instrument Will Be Started Tomorrow". New York Herald Tribune. June 2, 1929. p. F9. ProQuest 1111977225.

- ^ "Oratorio Society Gives 'Messiah'; Stoessel Leads Chorus of 250 Voices Augmented by New Organ of Carnegie Hall". The New York Times. December 28, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Robert E. Simon Dies at 58; Kin Of Morgenthau". New York Herald Tribune. September 8, 1935. p. 23. ProQuest 1317982631.

- ^ "Weisman Is Head of Carnegie Hall; Elected President to Succeed Late Robert E. Simon, Whose Son Is Made an Officer". The New York Times. September 29, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "M. Murray Weisman Carnegie Hall President: Managing Director Succeeds Late Robert E. Simon". New York Herald Tribune. September 29, 1935. p. 24. ProQuest 1237352810.

- ^ "Robert E. Simon Bust Unveiled In Carnegie Hall". New York Herald Tribune. May 6, 1936. p. 16. ProQuest 1237393750.

- ^ "R.E. Simon Lauded at Bust Unveiling; Tributes Paid to His Idealism in Preserving Carnegie Hall for Community Use". The New York Times. May 6, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Michael (February 16, 1987). "Sounds in the night". Time. 129 (7). Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ Stratigakos, Despina. "Elsa Mandelstamm Gidoni". Pioneerng Women of American Architecture. Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall History Timeline". CarnegieHall.org. The Carnegie Hall Corporation.

- ^ Taubman, Howard (April 28, 1955). "Orchestra to Bid on Carnegie Hall; Philharmonic May Lose Old Home Unless It Buys". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Press. pp. 1112–1113. ISBN 1-885254-02-4. OCLC 32159240.

- ^ "World of Music: Philharmonic Problem; Termination of the Carnegie Lease May Force Orchestra to Vacate in 1959". The New York Times. September 18, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Drive Set to Bar Sale of Carnegie; Hall's Superintendent Seeks Aid of Public to Prevent Destruction of Building". The New York Times. June 2, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Fowler, Glenn (July 25, 1956). "Music Landmark Brings 5 Million; Buyer of Carnegie Hall Offers to Resell to Orchestra but May Tear It Down Society Hopes to Move". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Time Inc (September 9, 1957). Life. pp. 91–. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ^ Callahan, John P. (August 8, 1957). "Red Tower Is Set for Carnegie Site; a Forty-four-story Office Building Is to Be Built Where Carnegie Hall Now Stands". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Red-and-gold Checks" (PDF). Architectural Forum. 107: 43. September 1957. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (July 4, 1958). "Longer Life Won by Carnegie Hall; Glickman Drops Plan to Buy Building as the Site for Big Red Skyscraper Property Off Market Decision Is Due on Whether Philharmonic Will Stay Till New Home Is Ready". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Plan to Raze Old Carnegie Hall Is Off: Realtor Drops Option on Landmark in New York". The Sun. July 21, 1958. p. 3. ProQuest 540427905.

- ^ Molleson, John (June 17, 1959). "Bids Residents Buy Carnegie Hall: Studio Tenant Urges 200 to Gel Together to Avert Demolition". New York Herald Tribune. p. 12. ProQuest 1323977017.

- ^ "New Unit Formed to Save Carnegie; Society Would Lease Hall if City Can Acquire It". The New York Times. March 31, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Molleson, John (March 31, 1960). "Mayor Aids Plan to Save Carnegie Hall: Pledges 'Fast Work' To Back Committee". New York Herald Tribune. p. 19. ProQuest 1325120353.

- ^ Talese, Gay (April 30, 1960). "Evictions Fought at Carnegie Hall; Landlord Presses Cases Despite City Plan to Save Famous Music House". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (September 21, 2015). "Robert E. Simon Jr., Who Created a Town, Reston, Va., Dies at 101". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Allen (July 22, 1960). "Carnegie Hall Getting New Paint And Upholstery for Fall Season". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Film Notes". New York Herald Tribune. May 29, 1961. p. 4. ProQuest 1326941243.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (May 29, 1961). "Italian Film Opens New Carnegie Hall Cinema". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Greenwood, Richard (May 30, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory: Carnegie Hall". National Park Service. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory: Carnegie Hall—Accompanying Photos". National Park Service. May 30, 1975. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall Designated as a 'National Landmark'". The New York Times. November 7, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall Made National Landmark". Democrat and Chronicle. November 7, 1964. p. 9. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Callahan, John P. (August 7, 1967). "Old Water Tower Now a Landmark; City Commission Designates Pillar on Harlem River and 10 Other Structures". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Rockwell, John (February 21, 1982). "Carnegie Hall Begins $20 Million Renovation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 731–732.

- ^ Schumach, Murray (November 14, 1977). "Carnegie Hall to End Its Live‐In Studios for Artists". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Shipp, E. r (October 21, 1980). "Carnegie Hall and City Negotiating On Renovation and Air-Rights Use". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Randy (October 21, 1980). "Mull sale of air rights over Carnegie Hall". New York Daily News. p. 65. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Gives $1.8 Million For Carnegie Renovation". The New York Times. January 21, 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (March 7, 1982). "A Superb Scheme for the Renovation of Carnegie Hall". The New York Times. p. D27. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 121888912. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goodman, Peter (July 4, 1982). "A building boom for the arts". Newsday. p. 117. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Shipp, E. r (October 21, 1980). "Carnegie Hall and City Negotiating On Renovation and Air-Rights Use". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Phelps, Timothy M. (January 18, 1981). "Carnegie Hall and Tenants Wrangle Over Rent Rises". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ King, Martin (April 2, 1982). "Tenants: Carnegie Hall is giving us the hook". New York Daily News. p. 94. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rockwell, John (May 17, 1985). "Carnegie Hall to Close for 7 Months Next Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Goodman, Peter (May 20, 1985). "Carnegie Hall renovations". Newsday. p. 118. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Rockwell, John (April 16, 1986). "Carnegie Hall's Plans". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Landmarks Panel Backs Carnegie Hall Project". The New York Times. July 25, 1985. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Purdum, Todd S. (January 5, 1986). "Art Slows Carnegie's Rebuilding". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (April 30, 1986). "Carnegie Hall Details Plans for Office Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Flynn, Kevin (April 30, 1986). "Carnegie Plans For Office Tower". Newsday. p. 21. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Shepard, Joan (April 30, 1986). "Deal will make Carnegie tall". New York Daily News. p. 103. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Larkin, Kathy (May 15, 1986). "They shutter to think of the future for hall". New York Daily News. p. 157. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Goodman, Peter (May 8, 1986). "Restoring Carnegie Hall to Its Glory". Newsday. p. 199. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Holland, Bernard (November 6, 1986). "Carnegie Recital Hall to Be Renamed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Rockwell, John (December 16, 1986). "Rejuvenated Carnegie Is Again Premier Hall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Whitaker, Barbara (December 16, 1986). "Reborn Splendor on 57th Street". Newsday. p. 4. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "History of the Hall: Timeline – 1986 Full interior renovation completed". Carnegie Hall. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Weill Recital Hall to Open With Festival". Newsday. January 3, 1987. p. 45. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Rockwell, John (January 6, 1987). "Weill Recital Hall Opens at Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Holland, Bernard (January 29, 1987). "Critic's Notebook; Setting the Right Tone for 'new' Carnegie Hall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (September 22, 1988). "Critic's Notebook; Seeking a Consensus on Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kozinn, Allan (September 14, 1995). "A Phantom Exposed: Concrete at Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Shepard, Richard F. (May 12, 1988). "Carnegie Hall Marks a Milestone for a Cornerstone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Soble, Ronald L. (May 13, 1989). "Carnegie Hall Seeks Mementos as 100th Birthday Approaches Musical, Cultural and Political History Taking Shape at Venerable N.Y. Site". Los Angeles Times. p. 14. ProQuest 280806961.

- ^ Koenenn, Joseph C. (April 23, 1991). "History From the Pockets of Tchiakovsky". Newsday. p. 60. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Zakariasen, Bill (April 23, 1991). "Carnegie halls out its history". New York Daily News. p. 31. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (February 8, 1992). "Music Notes; Composers Orchestra Defies the Conventional". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Rent the Shorin Club Room and Rohatyn Room". Carnegie Hall. April 3, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Deutsch, Claudia H. (October 11, 1992). "Commercial Property: Carnegie Hall; What's Playing? Maybe a Rousing Business Meeting". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Mangaliman, Jessie (November 21, 1987). "Expanding Carnegie Hall". Newsday. p. 15. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (September 20, 1995). "Case of the Carnegie Concrete, Chapter II". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Page, Tim (September 14, 1995). "Carnegie Hall Hopes New Floor Is a Sound One". Newsday. p. 8. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Oestreich, James R. (March 5, 1996). "Assessing Carnegie Hall Without the Concrete". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (December 14, 1998). "Carnegie Hall Expanding, Using Underground Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carnegie Delays Opening of Additional Hall". The New York Times. November 1, 2001. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "N.Y. Philharmonic, Carnegie Merger Off". Billboard. Associated Press. October 8, 2003. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (September 12, 2003). "A Three-Ring House of Music, Willing and Able to Surprise". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (September 15, 2003). "Music Review: Opening Weekend at Zankel Hall; Trash Cans on the Stage, a Subway Underfoot". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (September 12, 2003). "ARCHITECTURE REVIEW; Zankel Hall, Carnegie's Buried Treasure". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (November 25, 2005). "At Eclectic Zankel Hall, One Thing Rarely Varies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Gelder, Lawrence Van (March 4, 2006). "Arts, Briefly". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Frank, Robert (March 3, 2006). "Perelman's New Platform". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Dwyer, Jim (August 1, 2007). "A Requiem for Tenants of Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Carnegie Artist Tenants Fight Eviction". NPR.org. August 12, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Robbins, Liz (August 28, 2010). "In Apartments Above Carnegie Hall, a Coda for Longtime Residents". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Cooper, Michael (September 12, 2014). "Carnegie Hall Makes Room for Future Stars: Resnick Education Wing Prepares to Open at Carnegie Hall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Hernández, Javier C. (June 8, 2021). "Bruised by the Pandemic, Carnegie Hall Plans a Comeback". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Carnegie Hall reopens in October after 19-month closure". ABC News. June 8, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Playbill and CBS announcement, concert on November 14, 1943

- ^ Lee, Maureen D. (May 2012). Sissierettta Jones, "The Greatest Singer of Her Race," 1868–1933. University of South Carolina Press.

- ^ Hudson, Rob. "From Opera, Minstrelsy and Ragtime to Social Justice: An Overview of African American Performers at Carnegie Hall, 1892–1943". The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Stars assist the blind" (PDF). The New York Times. May 7, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "The Beatles at Carnegie Hall". It All Happened – A Living History of Live Music.

- ^ Wilson, John S. (February 13, 1964). "2,900-Voice Chorus Joins The Beatles" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Schaffner, Nicholas (July 1977). The Beatles Forever. New York: Fine Communications. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-56731-008-5.

- ^ "October 17, 1969, New York, NY US". Led Zeppelin Timeline. ledzeppelin.com. October 17, 1969. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ "This installment of our A to Z of Carnegie Hall series looks at the letter R—for 'Rock'". The A to Z of Carnegie Hall: R is for Rock 'n' Roll. September 22, 2012. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ "Ballet: Yugoslav Folk Art 'Tanec' Dancers Appear at Carnegie Hall in Display of Tremendous Skill". John Martin. The New York Times. January 28, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall Names Executive/Artistic Director". Billboard. June 1, 2005. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Clive Gillinson Biography". Carnegie Hall. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Binkowski, C.J. (2016). Opening Carnegie Hall: The Creation and First Performances of America's Premier Concert Stage. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4766-2398-6. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Hill, B. (2005). Classical. American Popular Music. Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8160-6976-7. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall's Historical Archival Collections Named as Carnegie Hall Susan W. Rose Archives". Carnegie Hall. February 9, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Cerf, Bennett (1956). The Life of the Party: A New Collection of Stories and Anecdotes. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. p. 335.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Carlson, Matt (April 10, 2020). "The Joke". Carnegie Hall. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Popik, Barry (July 5, 2004). "'How do you get to Carnegie Hall?' (joke)". The Big Apple. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pollak, Michael (November 29, 2009). "The Origins of That Famous Carnegie Hall Joke". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Lees, Gene (1988). Meet Me at Jim & Andy's: Jazz Musicians and Their World. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-504611-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e McLellan, Joseph (February 10, 1991). "The Hall That Carnegie Built". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Schonberg, Harold C. (December 28, 1987). "Critic's Notebook; Repertory of Legends Immortalizes Jascha Heifetz". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Agus, Ayke (2001). Heifetz As I Knew Him. Amadeus Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-57467-062-2.

- ^ "Music View". The New York Times. February 8, 1976. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

Sources[]

- "Historic Structures Report: Carnegie Hall". National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 29, 1962.

- Schickel, Richard (1960). The World of Carnegie Hall. Messner.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-177-9. OCLC 70267065. OL 22741487M.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carnegie Hall. |

- Official website

- Carnegie Hall at Google Cultural Institute

- Carnegie Hall and its events on NYC-ARTS.org

- Honors Performance Series, Carnegie Hall performance opportunity for elite student musicians

- Carnegie Hall

- 1891 establishments in New York (state)

- 57th Street (Manhattan)

- Andrew Carnegie

- Concert halls in New York City

- Event venues on the National Register of Historic Places in New York City

- Italian Renaissance Revival architecture in the United States

- Midtown Manhattan

- Music venues completed in 1891

- Music venues in Manhattan

- National Historic Landmarks in Manhattan

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- Seventh Avenue (Manhattan)

- Theatres in Manhattan

- Theatres on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan