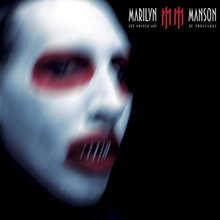

The Golden Age of Grotesque

| The Golden Age of Grotesque | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Marilyn Manson | ||||

| Released | May 7, 2003 | |||

| Recorded | 2002–2003 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 57:32 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Marilyn Manson chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Golden Age of Grotesque | ||||

| ||||

The Golden Age of Grotesque is the fifth studio album by American rock band Marilyn Manson. It was released on May 7, 2003, by Nothing and Interscope Records, and was their first album to feature former KMFDM member Tim Sköld, who joined after longtime bassist Twiggy Ramirez amicably left the group over creative differences. It was also their final studio album to feature keyboardist Madonna Wayne Gacy and guitarist John 5, who would both acrimoniously quit before the release of the band's next studio album.

The record was produced by Marilyn Manson and Sköld, with co-production from Ben Grosse. Musically, it is less metallic than the band's earlier work, instead being more electronic and beat-driven. This was done to avoid creating music similar to nu metal, a then-predominant genre of hard rock which the vocalist considered cliché. Manson collaborated with artist Gottfried Helnwein to create several projects associated with the album, including Doppelherz, a 25-minute surrealist short film which was released on limited edition units of the record as a bonus DVD. The Golden Age of Grotesque was also the title of the Manson's first art exhibition.

The album's lyrical content is relatively straightforward, and was inspired by the swing, burlesque, cabaret and vaudeville movements of Germany's Weimar Republic-era, specifically 1920s Berlin. In an extended metaphor, Manson compares his own work to the Entartete Kunst banned by the Nazi regime as he attempts to examine the mindset of lunatics and children during times of crisis. Several songs incorporate elements commonly found in playground chants and nursery rhymes. "Mobscene" (stylized as "mOBSCENE") and "This Is the New Shit" were released as singles, and a controversial music video was released for "Saint" (stylized as "(s)AINT").

The record received mixed reviews from mainstream music critics: some praised its concept and production, while others criticized its lyrics and described the album as uneven. Despite this, it was a commercial success, selling over 400,000 copies in Europe on its first week to debut at number one on Billboard's European Top 100 Albums. It also topped various national record charts, including Austria, Canada, Germany, Italy, Switzerland and the US Billboard 200. It was certified gold in many of these territories. "Mobscene" was nominated in the Best Metal Performance category at the 46th Annual Grammy Awards in 2004. The album was supported by the Grotesk Burlesk Tour.

Background and recording[]

After the band completed work on what became their triptych of albums (2000's Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death), 1998's Mechanical Animals and 1996's Antichrist Superstar), the band was free to begin a fresh project.[3] In late 2001, the eponymous vocalist worked with composer Marco Beltrami and former KMFDM multi-instrumentalist Tim Sköld to create an original score for the 2002 film Resident Evil. This was the second project on which Manson collaborated with Sköld, after the band's cover of "Tainted Love",[4] which became an international hit when released as a single from the Not Another Teen Movie OST in 2001.[5] The Resident Evil OST was released in March 2002, and included a remix of "The Fight Song" created by Slipknot drummer Joey Jordison.[6] The soundtrack to Queen of the Damned was also released that month, which featured Manson performing lead vocals on the Jonathan Davis-composed track "Redeemer".[7] On May 29, Sköld became an official band member when Twiggy Ramirez amicably left the group, citing creative differences.[8]

The album was produced by Manson, Sköld, and Ben Grosse.[9] It was recorded at Ocean Way Recording and the band's own Doppelherz Blood Treatment Facility in Los Angeles, as well as Grosse's The Mix Room in Burbank, California. Most of the songwriting effort was shared between Tim Sköld, John 5 and Manson,[10] with the latter describing it as the most focused record in the band's discography.[11] During the album's early stages of development, Manson indicated that both Jordison and Canadian musician Peaches had contributed to material,[12] although neither artist appears on the album.[10] Several songs on the record feature backing vocals by Andrew Baines of Tennessee, a 16-year-old fan who had been diagnosed with a terminal illness.[13] This collaboration had been facilitated by the Make-A-Wish Foundation, with Manson saying that he "wanted to make Andrew a permanent part of history, sealed up in distortion and megabytes of plastic."[14]

"We're in an era of music right now where heavy rock and aggressive things are very acceptable and very near approaching cliché. So it's important to keep pushing the boundary of how you make heavy music – and I want to continue to make really heavy music – but I want to do it in a way that isn't like everything else I hear when I turn on the radio."

— Marilyn Manson explaining the album's production aesthetic to MTV.[12]

"Para-Noir" contains a distinctive guitar solo from John 5, who performed it in one take using an unfamiliar, out-of-tune guitar whilst blindfolded.[3] "Ka-Boom Ka-Boom" was the final song composed for the record, and was written in response to criticism made by the head of the A&R division of Interscope Records, who said that the album "had no kaboom".[15] In a 2008 interview with a now-defunct fansite, Manson claimed to have performed the majority of the keyboards and synthesizer on the album, and not the band's longtime keyboardist Madonna Wayne Gacy. According to Manson, Gacy displayed little interest in contributing creatively, and eventually detached himself from the rest of the group to such a degree that he refused to attend studio sessions when informed that recording was to begin in June 2002. As a result, Manson received musical composition credits for eleven of the fifteen tracks on the record, in addition to his usual lyrical credits.[16]

Musically, the album is more electronic and beat-driven than preceding releases, with reviewers commenting that its sound is at times reminiscent of KMFDM. This has been attributed to Sköld,[17] who was a member of that band immediately prior to his arrival in Marilyn Manson.[3] It is also not as metallic as their earlier work, with Manson explaining to MTV that he wanted to create music which was dissimilar to the nu metal being played on radio at the time. He also noted the influence of early industrial rock acts such as Ministry, Big Black and Nitzer Ebb on the material.[12] Early twentieth-century German composer Kurt Weill was also claimed as an influence, along with the lucid dreams Manson was having during the album's production, elaborating that he would "wake up and say, 'I want to write a song that sounds like a stampeding elephant' or 'I want to write a song that sounds like a burning piano'."[18]

Themes and artwork[]

"This record is broken down to the simplest, most important thing, and that's relationships — whether they're between people or between ideas. I use analogies of art and decadence. How things in Berlin in the '30s got to such a great point, and some of the greatest things were created, and it was crushed by evil, jealous, bitter conservative powers. And the same thing happened in America, several times and continuously, with art and with myself."

— Marilyn Manson explaining the motivation behind the album's premise to MTV.[19]

The vocalist would later describe the period surrounding The Golden Age of Grotesque as being one of his most creative.[20] He was inspired by then-girlfriend, burlesque performance artist Dita Von Teese,[21] into exploring the decadent swing, burlesque, cabaret and vaudeville movements of Germany's Weimar Republic-era, specifically 1920s Berlin. He explained to Kerrang! that the album's content was inspired by "the lengths that people [in pre-Nazi Germany] went to in order to live their lives to the fullest and to make their entertainment as imaginative and extreme as possible."[22] He also found inspiration in the flamboyance of Dandyism, along with the cultural and artistic movements of Surrealism and Dadaism,[3] the life of the Marquis de Sade,[12] and the theater of the grotesque.[11]

Eschewing the lyrical depth and volume of symbolism found on Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) (2000), the album is relatively straightforward: its lyrical content primarily deals with relationships,[23] and, in an extended metaphor, Manson compares his own often-criticized work to the Entartete Kunst banned by the Nazi regime.[24] The record utilizes the narrative mode of stream of consciousness as Manson attempts to examine the response of the human psyche during times of crisis, particularly focusing on the mindset of lunatics and children. These were of particular interest to the vocalist, as "they don't follow the rules [of society]." Several songs incorporate elements commonly found in playground chants and nursery rhymes, which Manson would "pervert into something ugly and lurid."[18]

Manson began his long-term collaboration with Austrian-Irish artist Gottfried Helnwein in May 2002, collaborating on several projects associated with the album.[25] In addition to the album artwork, the pair created large-scale multi-media installation art pieces that would go on to be exhibited in various galleries throughout Europe and the United States.[26] These were also displayed at the album's launch party at The Key Club in Los Angeles.[27] They also worked together on the music video to lead single "Mobscene" (stylized as "mOBSCENE"),[28] as well as images which accompanied Manson's essay for The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum.[25] Helnwein later expressed disappointment that the latter was not selected as the album cover.[29] Many of the images found in the album artwork were inspired by illustrations found in Mel Gordon's 2000 book Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin.[30] Concerned that Gordon might take issue with use of the book's material, Manson called Gordon, who said he could not imagine a greater compliment than a popular music album based on an academic book.[31] The Golden Age of Grotesque was also the title of Manson's first art exhibition, which took place in September 2002 at the Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions Center.[32]

Release and promotion[]

On February 18, 2003, Manson revealed the album's release date and track listing via the band's official website.[33] The album was preceded by the release of its lead single, "Mobscene", which was serviced to mainstream and alternative rock radio formats on April 21. Its music video was directed by Manson and Thomas Kloss.[34] The single was backed by a remix of the song created by The Prodigy vocalist Keith Flint.[35] The song became one of the band's biggest worldwide hits, peaking in the top 20 of numerous national record charts,[36] and at number one in Portugal.[37] It peaked at number 18 on Billboard's Mainstream Rock Chart, making it their best-performing single on that chart since "The Dope Show" reached number 12 in 1998.[38] The song was nominated in the Best Metal Performance category at the 46th Annual Grammy Awards in 2004, losing out to Metallica's "St. Anger".[39]

A series of unique launch parties titled "Grotesque Burlesque" took place in advance of the album's US release on May 13.[26] The first of these occurred in Berlin on April 4,[34] followed by several more shows throughout Europe.[40] The final event took place at The Key Club in Los Angeles on May 12. These shows featured large-scale artwork by Helnwein and Manson, a burlesque performance by Von Teese, and an acoustic set from Manson backed by two female pianists.[27] Limited edition copies of the album included a DVD entitled Doppelherz (Double Heart), a 25-minute surrealist short film directed by Manson which featured art direction by Helnwein.[41] The film's audio consists of a repeating loop of album opener "Thaeter", accompanied by a stream-of-consciousness spoken-word recitation from Manson.[42]

On May 16, the band performed both "Mobscene" and "This Is the New Shit" on Jimmy Kimmel Live!.[43] The latter was released as the album's second single, and its music video was shot in Belgium on June 17 and featured over 100 fans.[44] A controversial music video was independently produced for the song "Saint" (stylized as "(s)AINT"). Directed by Asia Argento and containing scenes of violence, nudity, masturbation, drug-use and self-mutilation, Interscope considered it "too graphic" and refused to be associated with the project, although it was later included on international editions of the Lest We Forget: The Best Of bonus DVD.[45] NME referred to the video as "one of the most explicit music videos ever made",[46] and both Time and SF Weekly included it on their respective lists of the 'Most Controversial Music Videos'.[47][48]

The album was supported by the Grotesk Burlesk Tour,[49] with Peaches performing as opening act on select dates.[50] It began with a series of headlining shows in Europe, followed by the band's stint as one of the headlining acts at the 2003 Ozzfest.[23] Much of the elaborate attire and clothing worn by the band on tour was tailored by French fashion designer Jean-Paul Gaultier.[51] The stage was designed to resemble that of classic vaudeville and burlesque stage shows of the 1930s. Two female dancers would be present on stage for most of the show, and would be dressed in either vintage burlesque costumes or military uniforms and garters. They would also perform some live instrumentation, such as floor toms during "Doll-Dagga Buzz-Buzz Ziggety-Zag", and piano during "The Golden Age of Grotesque". They performed the latter whilst dressed to resemble conjoined twins. Manson would change his appearance numerous times throughout each show: he would wear elongated arms which he would swing in a marching manner as he walked along the stage, and would don blackface while wearing an Allgemeine SS-style peaked police cap or Mickey Mouse ears. The stage also utilized a series of elaborate platforms and pulpits, from atop of which he would quote random lines from Doppelherz between songs.[52] The tour was set to end with five concerts featuring Marilyn Manson opening for Jane's Addiction. However, these shows were cancelled by the latter band, with Perry Farrell citing exhaustion as the reason.[53]

Controversies[]

On June 30, 2003, the mutilated body of fourteen-year old schoolgirl Jodi Jones was discovered in woodland near her home in Easthouses, Scotland.[54] The injuries sustained by Jones closely resembled those of actress Elizabeth Short, who was murdered in 1947 and was popularly referred to by media as the Black Dahlia.[55][56] Jones' boyfriend, then-fifteen year old Luke Mitchell, was arrested on suspicion of her murder ten months later.[57] During a search of his home, detectives confiscated a copy of The Golden Age of Grotesque containing the short film Doppelherz.[58] It was purchased two days after Jones' death.[59] A ten-minute excerpt from the film, as well as several paintings by Manson depicting the Black Dahlia's mutilated body, were presented as evidence during the trial.[58][60][61]

Although Mitchell's defense attorney argued that Jones' injuries were inconsistent with those found in Manson's paintings,[62] Lord Nimmo Smith said during sentencing that he did "not feel able to ignore the fact that there was a degree of resemblance between the injuries inflicted on Jodi and those shown in the Marilyn Manson paintings of Elizabeth Short that we saw. I think that you carried an image of the paintings in your memory when you killed Jodi."[63] Mitchell was found guilty of murder and sentenced to serve a minimum of twenty years in prison.[64] Manson later dismissed claims that his work inspired the murder, arguing instead that "the education that parents give their children and the influences they receive" plays a more direct role in violent behavior, and criticised media who attempted to "[put] the blame elsewhere."[61]

The Golden Age of Grotesque is the final studio album to feature longtime keyboardist Madonna Wayne Gacy and guitarist John 5, who would both acrimoniously quit the group over the following years. John 5's relationship with Manson had soured over the course of the Grotesk Burlesk Tour. According to John, Manson spoke to him only once during the entire tour: "It was on my birthday and he turned to me and said, 'Happy birthday, faggot'—then walked away."[65] Manson also displayed hostility towards the guitarist on stage. During a performance of "The Beautiful People" at the 2003 Rock am Ring festival, Manson kicked and then shoved John, who responded in anger by throwing his guitar to the ground and raising his fists to Manson, before resuming the song.[66] Gacy, who was also the band's last remaining original member – excluding Manson – quit shortly before the recording of the band's next studio album, Eat Me, Drink Me (2007).[67] He would later file a $20 million lawsuit against Marilyn Manson for unpaid "partnership proceeds",[68] accusing the vocalist of spending money earned by the band on "sick and disturbing purchases of Nazi memorabilia and taxidermy, including the skeleton of a young Chinese girl."[69]

Critical reception[]

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 60/100[70] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Alternative Press | |

| Drowned in Sound | 7/10[73] |

| E! Online | B[74] |

| Entertainment Weekly | B−[75] |

| The Guardian | |

| Mojo | |

| PopMatters | 3/10[78] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

The album was released to mixed reviews. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, it received an average score 60, based on 12 reviews, which indicates "generally mixed or average reviews".[70] Although appearing on several publication's year-end lists for 2003,[81] other critics considered this to be the band's weakest album, arguing that it lacked thoughtful lyrics when compared to its predecessors. It won Metal Edge's 2004 Readers' Choice Award for "Album of the Year".[82]

Several publications praised the album's concept, and for being more humorous than the band's preceding albums. Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic said: "In an era when heavy rockers have no idea what happened in the '80s, much less the '30s, it's hard not to warm to this, even if his music isn't your own personal bag."[71] Barry McCallum of Independent Online called the album "reckless and uninhibited—but it's not all that hard to imagine Manson letting go; he's had fun here."[83] Chronicles of Chaos also praised its concept, and went on to say that it might be one of the best albums in the band's discography.[17] Alternative Press and Q each complimented the album's production,[72][79] while Billboard highlighted the album's lyrical content and Manson's "diatribes on religion, sex and prejudice."[84] Entertainment.ie called it an entertaining pop album, and summarized that "the pop world would be a much more boring place without [Marilyn Manson]—and that's what really counts."[2]

PopMatters argued that while the album has several excellent songs, it is hindered by "inane" lyrics.[78] BBC Music also criticized its lyrics,[85] while Chris Long of BBC Manchester argued that while Manson was capable of producing "the finest metal around", The Golden Age of Grotesque demonstrated him "losing his touch".[86] Barry Walters of Rolling Stone called the album uneven: praising its first half but criticizing the latter portion.[80] A writer for Now Toronto claimed that Manson was lapsing into self-parody, and complained the album was not heavy enough.[87] Although E! Online praised the band for being inventive, they said the album would not win over any new fans.[74] This sentiment was echoed by Entertainment Weekly, who called it "inventive and powerful enough to merit intermittent attention, but ultimately crushed by the weight of its hoary pretensions."[75]

Commercial performance[]

Industry forecasters predicted that The Golden Age of Grotesque was on course to become the band's second number one album on the Billboard 200, following 1998's Mechanical Animals, with estimated first-week sales of around 150,000 copies.[88] The album debuted at number one with first week sales of over 118,000 copies,[89] at the time the lowest opening week total for a number one-debuting studio album since Nielsen SoundScan began tracking sales data in 1991.[90] This figure was just 1,000 copies more than the first week sales of Holy Wood, which debuted at number thirteen in November 2000.[91] Sales of the album dipped to 45,000 copies on its second week, resulting in a positional drop on the Billboard 200 to number 21.[92] This broke the record previously held by Nine Inch Nails' 1999 album The Fragile for the largest drop from number one in the chart's history.[93] The Golden Age of Grotesque held this record until Incubus' Light Grenades dropped to number 37 in December 2006.[94] As of November 2008, the album has sold 526,000 copies in the US, making it the lowest-selling number one-debuting studio album of 2003. This was the second year the band achieved this, after Mechanical Animals became the lowest-selling number one-debuting studio album of 1998.[95] It also entered the Canadian Albums Chart at number one, selling 11,500 copies on its first week.[96]

The record was more successful internationally than the band's previous albums, particularly in Europe, where it sold over 400,000 copies during its first week to debut at number one on Billboard's European Top 100 Albums.[97] It topped various national record charts, namely Austria, Germany, Italy and Switzerland,[98] as well as the album chart of the Wallonia region of Belgium,[99] and the UK Rock & Metal Albums Chart.[100] It also peaked within the top five in France, Norway,[101] Portugal,[102] Spain, Sweden,[103] and the United Kingdom.[98] It attained gold certifications in several of these territories, including Austria (denoting 15,000 units),[104] Switzerland (20,000 units),[105] and France, Germany and the UK (100,000 copies each).[106][107][108] In Australasia, the album peaked at number five in both Australia and Japan,[109][110] and was certified gold in both countries for sales in excess of 35,000 and 100,000 copies, respectively.[111][112] It also peaked at number 16 in New Zealand.[113]

Track listing[]

All lyrics are written by Marilyn Manson.

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Thaeter" | 1:14 | |

| 2. | "This Is the New Shit" |

| 4:20 |

| 3. | "Mobscene" |

| 3:25 |

| 4. | "Doll-Dagga Buzz-Buzz Ziggety-Zag" |

| 4:11 |

| 5. | "Use Your Fist and Not Your Mouth" |

| 3:34 |

| 6. | "The Golden Age of Grotesque" |

| 4:05 |

| 7. | "Saint" |

| 3:42 |

| 8. | "Ka-Boom Ka-Boom" |

| 4:02 |

| 9. | "Slutgarden" |

| 4:06 |

| 10. | "♠" | John 5 | 4:34 |

| 11. | "Para-noir" |

| 6:01 |

| 12. | "The Bright Young Things" | John 5 | 4:19 |

| 13. | "Better of Two Evils" |

| 3:48 |

| 14. | "Vodevil" |

| 4:39 |

| 15. | "Obsequey (The Death of Art)" |

| 1:34 |

| Total length: | 57:32 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16. | "Tainted Love" (Gloria Jones cover; from Not Another Teen Movie) | Ed Cobb | 3:24 |

| Total length: | 60:56 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17. | "Baboon Rape Party" |

| 2:41 |

| Total length: | 63:37 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18. | "Paranoiac" |

| 3:57 |

| Total length: | 67:34 | ||

| No. | Title | Director | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Doppelherz" | Manson | 26:06 |

Notes

- "Mobscene" is stylized as "mOBSCENE".

- "Saint" is stylized as "(s)AINT".

- "♠" is listed as "Spade" on iTunes and Spotify

Personnel[]

Credits adapted from the liner notes of The Golden Age of Grotesque.[114]

- Recorded at the Doppelherz Blood Treatment Facility and at Ocean Way Recording in Los Angeles, with additional recording at The Mix Room in Burbank, California.

- Mixed at The Mix Room by Ben Grosse.

- Mastered by Tom Baker at Precision Mastering, Los Angeles.

Marilyn Manson

- Marilyn Manson – vocals, piano, keyboards, synthesizer bass, mellotron, saxophone, guitars, snare rolls, loops, digital editing, arrangements, producer, photography

- John 5 – guitars, piano, orchestration

- Tim Sköld – bass, guitars, accordion, keyboards, synth bass, loops, drum programming, digital editing, producer

- Madonna Wayne Gacy – keyboards, electronics, synthesizer

- Ginger Fish – drums, rhythm direction

Production

- Chuck Bailey – assistant engineer

- Andrew Baines – backing vocals

- Tom Baker – mastering

- Jon Blaine – hair stylist

- P. R. Brown – sleeve design

- Blumpy – digital editing

- Jeff Burns – assistant

- Ross Garfield – drum technician

- Ben Grosse – engineer, digital editing, producer, mixing

- Gottfried Helnwein – art direction

- Lily & Pat – vocals ("Mobscene" and "Para-noir")

- Perou – additional photography (inlay band photograph)

- Mark Williams – A&R

Charts[]

Weekly charts[]

|

Year-end charts[]

|

Certifications[]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[111] | Gold | 35,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[104] | Gold | 15,000* |

| France (SNEP)[142] | Gold | 120,000[106] |

| Germany (BVMI)[107] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[112] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| Portugal (AFP)[143] | Silver | 10,000^ |

| Russia (NFPF)[144] | Gold | 10,000* |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[105] | Gold | 20,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[108] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States | — | 526,000[95] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Release history[]

| Region | Date | Format | Label | Catalog # | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | May 7, 2003 |

|

Universal Music Japan | UICS-9083 | [145] |

| Germany | May 12, 2003 |

|

|

800065–6 | [146] |

| United Kingdom |

|

[147] | |||

| North America | May 13, 2003 |

|

9800080–9 | [148] | |

| Australia | May 25, 2003 |

|

Interscope | [149] |

See also[]

- List of Billboard 200 number-one albums of 2003

- List of European number-one hits of 2003

- List of number-one albums of 2003 (Canada)

- List of number-one hits of 2003 (Italy)

References[]

- ^ Miska, Brad (December 19, 2014). "[From Worst To Best] Marilyn Manson's Albums! #5: The Golden Age of Grotesque (2003)". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Music Review | Marilyn Manson - The Golden Age of Grotesque". entertainment.ie. May 20, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Revolver Staff (August 16, 2014). "Marilyn Manson: Survival of the Filthiest". Revolver. NewBay Media. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Wiederhorn, Jon (November 21, 2001). "Marilyn Manson Says Scoring Comes Naturally For Him". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Promis, Jose (September 27, 2003). "Missing Tracks Mean Fewer U.S. Album Sales". Billboard. 115 (39): 14. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ D'angelo, Joe (February 7, 2002). "Slipknot, Manson, Coal Chamber Wake The Dead With 'Resident Evil'". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ Moss, Corey (January 22, 2002). "Linkin Park, Manson, Disturbed Members 'Damned' By Korn's Davis". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ D'angelo, Joe (May 29, 2002). "Marilyn Manson Splits With Bassist Twiggy Ramirez". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ Saraceno, Christina (May 30, 2002). "Manson Bassist Ousted". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Golden Age of Grotesque [Japan Bonus Tracks] - Marilyn Manson | Release Info". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ a b D'angelo, Joe (October 28, 2002). "Marilyn Manson's Message: Be Bad, Look Good, Buy My DVD". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Wiederhorn, Jon (November 27, 2001). "Marilyn Manson Drawing From Ministry, Marquis De Sade". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson shows his softer side". Irish Examiner. Landmark Media Investments. August 31, 2002. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ NME Staff (August 29, 2002). "Fan-Tastic!". NME. Time Inc. UK. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Lane, Daniel (May 2003). "The Golden Age of Grotesque". Metal Hammer. No. 221. Future. p. 55. ISSN 0955-1190.

- ^ "The Heirophant - Everyone Will Suffer Now". MansonUSA. January 12, 2008. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ a b Hoose, Xander (June 3, 2003). "CoC: Marilyn Manson - The Golden Age of Grotesque : Review". Chronicles of Chaos. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Wiederhorn, Jon (May 12, 2003). "Marilyn Manson Draws From Dreams, Lunatics For Golden Age Of Grotesque". MTV. Viacom. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Dangelo, Joe (August 22, 2002). "Manson Says He's Stronger, Uglier With The Golden Age". MTV. Viacom Media Networks. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (April 25, 2012). "Marilyn Manson: 'The Villain Is Always the Catalyst'". Loudwire. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ Saul, Heather (March 24, 2016). "Dita Von Teese on remaining friends with Marilyn Manson: 'He encouraged all of my eccentricities'". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Winwood, Ian (March 23, 2002). "Paranoia, Jail Sentences, September 11 and Kittens?". Kerrang!. No. 896. Bauer Media Group. pp. 24–29. ISSN 0262-6624.

- ^ a b Moss, Corey (February 26, 2003). "Manson Wants To Perform With Siamese Twins For Nude Crowds". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson über Stimmung in USA und "Entartete Kunst"" [Marilyn Manson on the mood in the US and "Degenerate Art"]. Der Standard (in German). May 5, 2003. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Kerrang! News Staff (February 2003). "Reich 'n' Roll! Marilyn Manson Shocking New Images Revealed". Kerrang!. No. 941. Bauer Media Group. p. 12. ISSN 0262-6624.

- ^ a b "Marilyn Manson: 'The Golden Age Of Grotesque' Cover Art Posted Online". Blabbermouth.net. February 19, 2003. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ a b (May 15, 2003). "A Dope Show". LA Weekly. Voice Media Group. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ Sweet, Laura (June 6, 2009). "Gottfried Helnwein's Controversial Photos Of Marilyn Manson Available As Prints". If It's Hip, It's Here. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ Helnwein, Gottfried (September 1, 2003). "Album Covers That Never Were". Gottfried Helnwein. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ "Voluptuous Panic | Feral House". Feral House. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ "Show #49: The Hipster Whores of Weimar Germany: Mel Gordon pt. 2". R. U. Sirius. June 20, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ Moss, Corey (September 20, 2002). "Marilyn Manson Brings 'Ass-Stabbing Fun' To Fore At Gallery Exhibit". MTV News. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson Set Release Date For 'The Golden Age Of Grotesque'". Blabbermouth.net. February 18, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Wiederhorn, Jon (April 4, 2003). "Manson Plays Ringmaster At Creepy Carnival In Latest Video". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "The Prodigy's Keith Flint Remixes Marilyn Manson's New Single". Blabbermouth.net. April 23, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Hits of the World". Billboard. Nielsen Media Research. 115 (20): 50–51. May 17, 2003. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ "Hits of the World". Billboard. Nielsen Media Research. 115 (21): 45. May 24, 2003. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson - Chart History - Mainstream Rock Songs". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Lee McKinstry (February 6, 2015). "20 artists you may not have known were nominated for (and won) Grammy Awards". Alternative Press. Alternative Press Magazine, Inc. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ NME Staff (April 23, 2003). "Baby's Done A Remix!". NME. Time Inc. UK. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "DOPPELHERZ | Film Threat". Film Threat. June 2, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson - The Golden Age of Grotesque". Metal Reviews. June 16, 2003. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson To Appear On 'Jimmy Kimmel Live!'". Blabbermouth.net. May 9, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson: 'This Is The New Shit' Video Shot In Belgium". Blabbermouth.net. July 3, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ Montgomery, James (September 22, 2004). "Marilyn Manson Calls Lest We Forget 'A Farewell Compilation'". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ NME Staff (June 17, 2016). "NSFW! – It's The 18 Most Explicit Music Videos Ever". NME. Time Inc. UK. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (June 6, 2011). "'(S)aint' | Top 10 Controversial Music Videos". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Schaffer, Dean (August 1, 2011). "MTV at 30: The Top 10 Most Controversial Music Videos (NSFW)". SF Weekly. San Francisco Media Co. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Schwarz, Hunter (September 8, 2014). "Arnold Schwarzenegger's gubernatorial portrait was done by a man who's photographed Marilyn Manson for his tour". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (November 27, 2003). "Marilyn Manson/Peaches, Manchester Arena". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ MTV News Staff (April 28, 2003). "For The Record: Quick News on Marilyn Manson and Jean Paul Gaultier". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Empire, Kitty (June 8, 2003). "Pop: It's OK, he won't bite..." The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Jane's Addiction scotches tour". TODAY.com. December 19, 2003. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ Glendinning, Lee (May 16, 2008). "Luke Mitchell loses appeal in Jodi Jones murder". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Cramb, Auslan (January 7, 2005). "Jodi Jones death 'similar to Hollywood killing'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ PA (January 21, 2005). "Teenager convicted of Jodi murder | Crime | News". The Independent. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "UK | Scotland | Killer 'obsessed by occult'". BBC News. January 21, 2005. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Bychawski, Adam (December 24, 2004). "Marilyn Manson DVD Played In Murder Trial". NME. Time Inc. UK. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Peterkin, Tom (January 22, 2005). "Jodi killed by boyfriend attracted to sex, drugs and Satan". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "I did not inspire Jodi's killer, says rock star Marilyn Manson". The Scotsman. Johnston Press. February 14, 2005. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ a b PA (February 14, 2005). "Blame Jodi killer's upbringing: Manson". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Defense Lawyer: No Connection Between Murder And Marilyn Manson Paintings". Blabbermouth.net. January 8, 2005. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Kirsty (February 12, 2005). "Jodi's killer to serve at least 20 years in jail | UK news". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "Murderer Luke Mitchell has latest appeal over Jodi Jones conviction rejected". STV. April 15, 2011. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Wiederhorn, Jon (April 6, 2004). "Fired Marilyn Manson Guitarist Wonders What Went Wrong". MTV News. Viacom. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ Suehs, Bob (March 26, 2006). "John 5 – Interview". Rock N Roll Experience. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ Clarke, Betty (December 7, 2007). "Marilyn Manson, Wembley Arena, London". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Ex-Bandmate Sues Marilyn Manson". CBS News. August 5, 2007. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ DiVita, Joe (February 1, 2016). "Former Marilyn Manson Keyboardist Stephen Bier Says Manson Should 'Put a Bullet In His Head'". Loudwire. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "Critic Reviews for The Golden Age Of Grotesque". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Golden Age of Grotesque – Marilyn Manson". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Marilyn Manson: The Golden Age of Grotesque". Alternative Press. July 2003. p. 117. ISSN 1065-1667.

- ^ Price, Dale (May 20, 2003). "Album Review: Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age Of Grotesque". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ a b E! Online Staff (May 12, 2003). "E! Online - Music - Marilyn Manson "The Golden Age of Grotesque"". E! Online. Archived from the original on May 28, 2003. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Greer, Jim (May 16, 2003). "The Golden Age Of Grotesque". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (May 9, 2003). "Marilyn Manson: The Golden Age of Grotesque". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson: The Golden Age of Grotesque". Mojo. June 2003. p. 100. ISSN 1351-0193.

- ^ a b Hreha, Scott (August 26, 2003). "Marilyn Manson: The Golden Age of Grotesque". PopMatters. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Marilyn Manson: The Golden Age of Grotesque". Q. Bauer Media Group. June 2003. p. 103. ISSN 0955-4955.

- ^ a b Walter, Barry (May 6, 2003). "Marilyn Manson: The Golden Age Of Grotesque". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Marilyn Manson – Biography & History". AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ Metal Edge Staff (June 2004). "Readers' Choice Awards: The Results". Metal Edge. Los Angeles, California: Zenbu Media. pp. 12–41. ISSN 1068-2872.

- ^ "The Golden Age of Grotesque". Independent Online. June 4, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ Flick, Larry (May 24, 2003). "Billboard | Reviews & Previews | Albums". Billboard. Vol. 115 no. 21. Nielsen Business Media. p. 34. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ Chambers, Catherine (May 29, 2003). "BBC Music - Review of Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age Of Grotesque". BBC Music. Archived from the original on February 12, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Long, Chris (May 19, 2003). "BBC - Manchester Music - Marilyn Manson - The Golden Age of Grotesque". BBC Manchester. Archived from the original on August 22, 2003. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ Perlich, Tim (May 15, 2003). "Marilyn Manson - NOW Magazine". Now. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ Mayfield, Geoff (May 24, 2003). "A Look Ahead | Manson Bids To Be 'Golden' Boy". Billboard. Nielsen Media Research. 115 (21): 10. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Martens, Todd (May 21, 2003). "Marilyn Manson Posts 'Grotesque' At No. 1". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Mayfield, Geoff (May 31, 2003). "Over The Counter | Of Moms And Manson". Billboard. Nielsen Media Research. 115 (22): 87. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Dansby, Andrew (May 21, 2003). "Manson Golden at Number One". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ "Staind, Deftones Rock Billboard Album Chart". Billboard. May 28, 2003. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Bronson, Fred (June 7, 2003). "'Fragile' Record Broken". Billboard. Nielsen Media Research. 115 (23): 86. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Hasty, Katie (December 13, 2006). "Ciara, Eminem, Stefani Overtake The Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Grein, Paul (November 21, 2008). "Chart Watch Extra: What A Turkey! The 25 Worst-Selling #1 Albums". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on September 26, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Williams, John (May 21, 2003). "Marilyn Manson debuts at No. 1". Jam!. Archived from the original on August 3, 2004. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Sexton, Paul (May 26, 2003). "Kelly, Timberlake Continue U.K. Chart Reign". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Hits Of The World". Billboard. 115 (22): 80–81. May 31, 2003. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ a b "Ultratop.be – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Official Rock & Metal Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Norwegiancharts.com – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Portuguesecharts.com – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Swedishcharts.com – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Austrian album certifications – Marilyn Manson – Golden Age of Grotesque" (in German). IFPI Austria. May 16, 2003. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards (Marilyn Manson; 'The Golden Age of Grotesque')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Les Albums Or" (in French). InfoDisc. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ^ a b "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Marilyn Manson; 'The Golden Age of Grotesque')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "British album certifications – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". British Phonographic Industry. June 20, 2003. Retrieved October 18, 2016.Select albums in the Format field. Select Gold in the Certification field. Type The Golden Age of Grotesque in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ a b "Australiancharts.com – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b マリリン・マンソンのアルバム売り上げランキング [Marilyn Manson album sales ranking] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2003 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Japanese album certifications – マリリン・マンソン – ザ・ゴールデン・エイジ・オブ・グロテスク" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved October 18, 2016. Select 2003年5月 on the drop-down menu

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ The Golden Age of Grotesque (CD liner notes). Marilyn Manson. Interscope Records. 2003. 9800065.CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

- ^ "Heavy Rock & Metal – Week Commencing 26th May 2003" (PDF). ARIA Charts (692): 12. May 26, 2003. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Sexton, Paul (May 26, 2003). "Kelly, Timberlake Continue U.K. Chart Reign". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson: The Golden Age of Grotesque" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Greek Albums Chart". IFPI Greece. June 8, 2003. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2003. 21. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week 20, 2003". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ 18, 2003/40/ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Hits of the World". Billboard. Vol. 115 no. 22. May 31, 2003. p. 80. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Marilyn Manson Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – End Of Year Charts – Heavy Rock & Metal Albums 2003". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 2003" (in German). austriancharts.at. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 2003 – Albums" (in French). Ultratop. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Top de l'année Top Albums 2003" (in French). SNEP. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts – 2003" (in German). Offizielle Deutsche Charts. GfK Entertainment. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Swiss Year-End Charts 2007". swisscharts.com. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "The Official UK Albums Chart" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. 2003. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "French album certifications – Marylin Manson – The Golden of Grotesque" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. August 21, 2003. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ "Portuguese album certifications – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque". Clix Música (in Portuguese). Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa. Archived from the original on July 3, 2003. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Russian album certifications – Marilyn Manson – The Golden Age of Grotesque" (in Russian). National Federation of Phonogram Producers (NFPF). Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ "ザ・ゴールデン・エイジ・オブ・グロテスク 【CD】" [Marilyn Manson - The Golden Age of Grotesque [CD]]. Universal Music Japan (in Japanese). Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "The Golden Age of Grotesque - Marilyn Manson: Amazon.de". Amazon.de. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "The Golden Age of Grotesque [VINYL] - Marilyn Manson: Amazon.co.uk". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "The Golden Age of Grotesque - Marilyn Manson: Amazon.co.uk". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "JB Hi-Fi | The Golden Age of Grotesque, Marilyn Manson". JB Hi-Fi. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- 2003 albums

- Albums produced by Marilyn Manson

- Burlesque

- Glam rock albums by American artists

- Interscope Geffen A&M Records albums

- Interscope Records albums

- Marilyn Manson (band) albums

- Nothing Records albums

- Political music albums by American artists