The Lair of the White Worm (film)

| The Lair of the White Worm | |

|---|---|

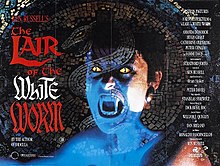

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Russell |

| Screenplay by | Ken Russell |

| Based on | The Lair of the White Worm by Bram Stoker |

| Produced by | Dan Ireland William J. Quigley Ken Russell Ronaldo Vasconcellos |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dick Bush |

| Edited by | Peter Davies |

| Music by | Stanislas Syrewicz |

Production company | White Lair |

| Distributed by | Vestron Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 93 min. |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[1] |

| Box office | $1,189,315 (US)[2] |

The Lair of the White Worm is a 1988 British horror film based loosely on the 1911 Bram Stoker novel of the same name and drawing upon the English legend of the Lambton Worm. The film was written and directed by Ken Russell and stars Amanda Donohoe and Hugh Grant.

Plot[]

Angus Flint (Peter Capaldi) is a Scottish archaeology student excavating the site of a convent at the Derbyshire bed and breakfast run by the Trent sisters, Mary (Sammi Davis) and Eve (Catherine Oxenberg). He unearths an unusual skull which appears to be that of a large snake. Angus believes it may be connected to the local legend of the d'Ampton 'worm', a mythical snake-like creature from ages past said to have been slain in Stonerich Cavern by John d'Ampton, the ancestor of current Lord of the Manor, James d'Ampton (Hugh Grant).

When a pocket watch is discovered in Stonerich Cavern, James comes to believe that the d'Ampton worm may be more than a legend. The watch belonged to the Trent sisters' father, who disappeared a year earlier near Temple House, the stately home of the beautiful and seductive Lady Sylvia Marsh (Amanda Donohoe).

The enigmatic Lady Sylvia is in fact an immortal priestess to the ancient snake god, Dionin. As James correctly predicted, the giant snake roams the caves which connect Temple House with Stonerich Cavern. Lady Sylvia steals the skull and abducts Eve Trent, intending to offer her as the latest in a long line of sacrifices to her snake-god.

Before Lady Sylvia can execute her evil plan, Angus and James rescue Eve and destroy both Lady Sylvia and the giant snake. However, Lady Sylvia bites Angus before she dies, and Angus finds himself cursed to carry on the vampiric, snake-like condition, after he finds, to his shock, that the snake anti-venom he used was actually a new form of arthritis medication he got by mistake. When Lord D'Ampton invites him for a dinner celebration, Angus sinisterly smiles and accepts his offer.

Cast[]

- Hugh Grant as Lord James D'Ampton

- Amanda Donohoe as Lady Sylvia Marsh

- Catherine Oxenberg as Eve Trent

- Peter Capaldi as Angus Flint

- Sammi Davis as Mary Trent

- Stratford Johns as Peters

- Paul Brooke as Ernie

- Imogen Claire as Dorothy Trent

- Chris Pitt as Kevin

- Gina McKee as Nurse Gladwell

- Christopher Gable as Joe Trent

Production[]

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (December 2019) |

Development[]

The movie was made as part of a three-picture deal Russell had with Vestron Pictures following the success of Russell's Gothic (1986). Vestron told their executive Dan Ireland, who was an admirer of Russell, that if the director could come up with a horror movie, they would finance his planned prequel to Women in Love, The Rainbow (eventually filmed in 1989).[3]

Russell was an admirer of Bram Stoker and had written an adaptation of Dracula that had never been filmed. Someone suggested the director read Lair of the White Worm which Stoker wrote shortly before his death.[1]

Script[]

Russell was "disappointed" by the novel. "There are touches of the master there. Dracula is a masterful novel: the psychological game the book plays is very interesting, and the Freudian elements are very deep, but those aspects are not present in Worm. What I did find was something else that took its place, in a sense, and that was for once you didn't have to go to Transylvania for the terror, it happened up the road in Derbyshire."[1]

He added that "Stoker tried to write something beyond what he'd already written in Dracula. Unfortunately, his faculties had given way, and he couldn’t realize his imagination. It seems potentially more imaginative than Dracula, yet falls far short of itself in terms of credibility.” [1]

Russell said "It's very similar to Dracula, but instead of being gothic, it's a very English story . . . Instead of bats, it has a snake, and instead of a man, a woman."[4]

The director thought "the term 'horror movie' covered a whole strata of possibilities" and he thought Lair, "while it "certainly has plenty of horror elements to it... I consider it to be more of a whodunnit thriller in one respect— or more precisely, a what-dunnit."[1]

Russell used the song "The Lambton Worm" in the film.[1]

Russell says he took "the spine of the novel and used that as the film's backbone, and that is the snake-worshipping cult. Stoker created a rather ineffectual villain; it’s the villainess who interested me more, the priestess who caters to the dietary needs of the worm. The worm really is the character that steals the show. And as with the Loch Ness monster... there is the assumption that a land-based creature of this sort could still exist under the right conditions— which in the story is this huge cavern called Thor’s Cave in Derbyshire, located next to a snake-like river."[1]

Russell said he thought the story would have "more credibility if set in modern times" and based the characters on "interesting people I know in the wilds where I live in the Lake District."[1]

Casting[]

Ireland says that Russell originally wanted to cast Tilda Swinton, but she turned down the role after reading the script. Amanda Donohoe was cast instead. Ireland also claims that Russell made the film partly as a tribute to Oscar Wilde.[3]

Donohoe says Russell sent her a script with a note saying "I don't know if you'll be interested in this little bit of nonsense but please read it anyway." She read it and agreed to play Lady Sylvia because, she said, it gave her "the opportunity to play a woman who is basically a fantasy woman. There are no boundaries. Therefore, I could do exactly as I chose with that lady.... I didn't want her to be some sort of vampire bimbo. I really wanted her to be a sort of incredibly sophisticated and ageless woman."[5]

"I always admire someone who really dares to be bad," said Donohoe of Russell. "Even his actors - people like Oliver Reed - have always impressed me that way. They can be brilliant or perfectly dreadful, but they're never boring. I'm fairly serious about acting and integrity, that films should have some real vrumph to them and say something about life. And I'd just been on this string of films and television films in the last two years, all pretty heavy stuff, and I thought 'Well, why not do a film that doesn't mean anything at all?'"[6]

Russell said Vestron wanted an American name and suggested Catherine Oxenberg, who had been in Dynasty. Russell agreed although he said Oxenberg refused to be naked in the final sacrifice sequence, insisting on doing it in her underwear. Russell later wrote "being of royal lineage, she opted for Harrods' silk but as we were a low budget movie she had to be content with Marks and Spencer's cotton - and very fetching she was too."[7]

It was one of Hugh Grant's first movies and Ireland says Grant was "embarrassed by it" in later years.[3] "I'm not sure if it was meant to be horrific or funny," Grant said shortly after the film was made. "When I saw it, I roared with laughter. As ever, I get to play a sort of upper-class young man. I have some exciting things to do: I get to slay a giant worm with a big sword, cutting it in half. Very, very symbolic stuff."[8]

Filming[]

The film was shot on location and at Shepperton Film Studios in England over a seven-week period from mid-February to mid-April, 1988.[9]

Russell said it was a difficult shoot because “Special effects take forever to do. and we had to schedule things in such a way so that we didn't lose any time. Sometimes we’d have two crews shooting simultaneously on different soundstages: One was shooting on the shrine set with Catherine Oxenberg about to be sacrificed to the worm, while other, we were filming a convent of nuns about to be raped by a legion of centurions. Never a dull moment.” [1]

Referring to aspects of the movie's visual style, Slant wrote: "Russell layers visual elements—faces, bodies, flames—into the video footage using chroma-key compositing, achieving a disorienting surrealist-collage effect".[10]

"Ken loves danger," said Donohoe. "One day he came in and played a tape for me and Hugh Grant of a drawing room comedy with Noël Coward and Gertrude Lawrence. Afterwards, we just looked at him with blank faces and he said `That's the way I want you to play your scenes.' It was mad but inspired."[11]

Russell insisted the film was a comedy. "“Audiences don’t realize my films are comedies until the last line has been delivered, and even then, most people don’t appear to get the joke," he said. "I would like to state that I actively encourage the audience to laugh along with White Worm."[1]

Critical reception[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (August 2016) |

On movie review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, as of October 2020, the film had an approval rating of 67%, based on 27 reviews, with an average rating of 5.82/10.[12]

Roger Ebert gave it two stars out of four and called it "a respectable B-grade monster movie."[13]

Variety called it "a rollicking, terrifying, post-psychedelic headtrip."[14]

Russell said the movie "became a cult film, appropriately enough, down under. It did well in other countries, but not in Merrie England, where our dour-faced critics insisted on taking it seriously. How on earth can you take seriously the vision of Catherine Oxenberg, dressed in Marks & Spencer’s underwear, being sacrificed to a fake, phallic worm two hundred feet long?"[15]

Russell later used Donohoe and Davis in The Rainbow.[16]

Donohoe says there was some talk of a sequel but none was made.[17]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Nutman, Philip (December 1988). "A Descent into Lair of the White Worm". Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help)Fangoria, No. 79. O'Quinn Studios. Pages 35-39. - ^ The Lair of the White Worm at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Dan Ireland on The Lair of the White Worm". Trailers from Hell on You Tube.

- ^ Outrageous movie director's wild about Oscar Dan Yakir Toronto Star 18 May 1988: D1.

- ^ AT THE MOVIES Gelder, Lawrence Van. New York Times 21 Oct 1988: C.10.

- ^ Lacey, Liam (12 October 1988). "Amanda Donohoe had her doubts about doing a horror flick". The Globe and Mail. p. C5.

- ^ Russell, Ken (1991). Altered States. Bantam Books. p. 295.

- ^ Dabby, Victor (13 July 1988). "IN PERSON 'It's frightfully good stuff' Actor revels in bon vivant role". The Globe and Mail. p. C8.

- ^ THE MOVIE CHART: [Home Edition] Los Angeles Times 28 Feb 1988: 38.

- ^ Wilkins, Budd (9 February 2017). "The Lair of the White Worm | Blu-Ray Review | Slant Magazine". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Nothing to Hide: [Home Edition] Klady, Leonard. Los Angeles Times 19 Nov 1988: 1.

- ^ "The Lair of the White Worm (1988)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (11 November 1988). "Lair Of The White Worm :: rogerebert.com :: Reviews". rogerebert.suntimes.com. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ "The Lair of the White Worm". Variety. 31 December 1988. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Russell, Ken (1994). The Lion Roars. Starbrite. p. 145.

- ^ Rainbow warrior: After twenty years Ken Russell films Lawrence again Malcolm, Derek. The Guardian 18 Aug 1988: 23.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (17 December 2015). "Interview: Amanda Donohoe on Ken Russell's THE LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM". Coming Soon.

External links[]

- The Lair of the White Worm at IMDb

- Review of film at Variety

- My Guilty Pleasre: Lair of the White Worm at The Guardian

- 1988 films

- English-language films

- 1988 horror films

- British comedy horror films

- British monster movies

- Folk horror films

- British films

- Films shot at Elstree Studios

- 1980s monster movies

- Films based on horror novels

- Films based on works by Bram Stoker

- Films directed by Ken Russell

- Films set in Derbyshire

- Vampires in film

- Films based on Irish novels

- Films about human sacrifice