The Naked City

| The Naked City | |

|---|---|

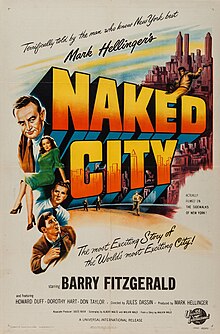

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jules Dassin |

| Screenplay by | Albert Maltz Malvin Wald |

| Story by | Malvin Wald |

| Produced by | Mark Hellinger |

| Starring | Barry Fitzgerald Howard Duff Dorothy Hart Don Taylor |

| Cinematography | William H. Daniels |

| Edited by | Paul Weatherwax |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa Frank Skinner |

Production company | Mark Hellinger Productions |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2.4 million[1] |

The Naked City (aka Naked City) is a 1948 American film noir directed by Jules Dassin. Based on a story by Malvin Wald, with a screen play by Wald and Albert Maltz, the film depicts the police investigation that follows the murder of a young model, incorporating heavy elements of police procedure. A veteran cop is placed in charge of the case and he sets about, with the help of other beat cops and detectives, to find the girl's killer. The film, shot partially in documentary style, was filmed on location on the streets of New York City and features landmarks such as the Williamsburg Bridge, the Whitehall Building, and an apartment building on West 83rd Street in Manhattan as the scene of the murder.

The film received two Academy Awards, one for cinematography for William H. Daniels and another for film editing to Paul Weatherwax.[2] In 2007, The Naked City was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3]

Plot[]

In the late hours of a hot New York summer night, a pair of men subdue and kill Jean Dexter, an ex-model, by knocking her out with chloroform and drowning her in her bathtub. When one of the murderers gets conscience-stricken while drunk, the other kills him and throws his body into the East River.

Homicide Detective Lt. Dan Muldoon and his young associate, Det. Jimmy Halloran, are assigned to Jean's case, which the medical examination has determined was murder. Muldoon has been a homicide cop for 22 years, Halloran for three months. At the scene, the police interrogate Martha Swenson, Jean's housekeeper, about Jean's boyfriends, and she tells them about a "Mr. Philip Henderson". They also discover a bottle of sleeping pills and her address book. Halloran questions the doctor who prescribed the pills, Lawrence Stoneman, and Ruth Morrison, another model and Jean's friend. Back at the police station, Muldoon questions Frank Niles, Jean's ex-boyfriend, who lies about everything, claiming only a business relationship with Jean and denying knowing Ruth. Because of his lies, Niles becomes the prime suspect. Later, Muldoon deduces from the bruises on Jean's neck that she was killed by at least two men.

That evening, Jean's parents, Mr. and Mrs. Batory, from whom Jean was estranged, arrive in New York to formally identify the body and tell the detectives that they have no knowledge of Jean's acquaintances. The next morning, the detectives learn that Niles sold a gold cigarette case stolen from Stoneman, then purchased a one-way airline ticket to Mexico. They also discover that one of Jean's rings was stolen from the home of a wealthy Mrs. Hylton. At Mrs. Hylton's Park Avenue apartment, the police learn that the ring actually belonged to her socialite daughter, who, to their surprise, turns out to be Ruth Morrison (having retained the name of Mrs. Hylton's previous husband).

Learning that Ruth's engagement ring is also stolen property, and that she is engaged to Niles, Muldoon and Halloran take Ruth to Niles' apartment, where they coincidentally interrupt someone trying to murder him. The killer takes a shot at the cops and escapes down the fire escape onto the nearby elevated train. When questioned about the stolen jewelry, Niles claims that they were all presents from Jean, which reveals his true relationship with her, much to Ruth's chagrin. Ruth realizes she is engaged to a swindler and slaps him. Niles is then arrested for the jewel thefts, but the murder case remains open.

Halloran learns that a body recovered from the East River, is that of small-time burglar Peter Backalis, who died within hours of the Dexter murder, and Halloran believes the two incidents are connected. Muldoon, although skeptical, lets him pursue the lead and assigns two veteran detectives on the squad to help Halloran with the legwork. Through further methodical but tedious investigation, Halloran discovers that Backalis's accomplice on a jewelry store burglary was Willie Garzah, a former wrestler who plays the harmonica. While Halloran and his team canvass the Lower East Side of New York using an old publicity photograph of Garzah, Muldoon compels Niles to identify Jean's mystery boyfriend. He reveals that Dr. Stoneman is "Henderson". At Stoneman's office, Muldoon uses Niles to trap the married, respectable physician into confessing that he fell in love with Jean, only to learn that she and Niles were using him in order to rob his society friends. Niles then confesses that Garzah killed Jean and Backalis. Halloran and Muldoon, using different approaches, have come up with the same killer.

Meanwhile, Halloran finally locates Garzah and, pretending that Backalis is in the hospital, tries to trick Garzah into accompanying him, but Garzah (knowing he killed Backalis) sees through the ruse. The ex-wrestler rabbit punches the rookie detective, momentarily knocking him unconscious. Garzah attempts to disappear in the crowded city, but as police descend upon the neighborhood, he panics and draws attention to himself when he shoots and kills a blind man's guide dog on the pedestrian walk of the Williamsburg Bridge. Garzah attempts to flee over the bridge but, as police approach from both directions, he starts climbing one of the towers and is shot and wounded. High on the tower, Garzah refuses to surrender; gunfire is exchanged, and he is hit again and falls to his death.

As the skyline and street shots of New York are shown and a trashman sweeps up yesterday's newspapers, the narration concludes by saying "There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them."

Cast[]

- Barry Fitzgerald as Detective Lt. Dan Muldoon

- Howard Duff as Frank Niles

- Dorothy Hart as Ruth Morrison

- Don Taylor as Detective Jimmy Halloran

- Frank Conroy as Captain Donahue

- Ted de Corsia as Willie Garzah

- House Jameson as Dr. Lawrence Stoneman

- Anne Sargent as Mrs. Halloran

- Adelaide Klein as Mrs. Paula Batory

- Grover Burgess as Mr. Batory

- Tom Pedi as Detective Perelli

- Enid Markey as Mrs. Edgar Hylton

- Walter Burke as Pete Backalis

- Virginia Mullen as Martha Swenson

- Mark Hellinger as Narrator

Production[]

Producer Mark Hellinger, who also narrated the film, was only 44 when he died of a heart attack on December 21, 1947, after reviewing the final cut of the film at his home.[4]

The visual style of The Naked City was inspired by New York photographer Weegee, who published a book of photographs of New York life titled Naked City (1945).[5] Weegee was hired as a visual consultant on the film, and is credited with helping to craft its imagery.[6] But film historian William Park has argued that, despite Weegee's work on the film and its title coming from Weegee's earlier work, the film owes its visual style more to Italian neorealism rather than Weegee's photographic work.[7]

The movie features the uncredited film debuts of Kathleen Freeman, Bruce Gordon, James Gregory, Nehemiah Persoff, and John Randolph in small roles. Randolph, along with Paul Ford, who also had a small part, was appearing at the time on the New York stage in Command Decision. John Marley, Arthur O'Connell, David Opatoshu, and Molly Picon had small, uncredited roles.

The musical scoring process was contentious. Hellinger allowed Dassin to assign a former M-G-M colleague, the arranger George Bassman, to compose the music. Hellinger found this so unsatisfactory that, on the night before he died, he begged his own first choice, Miklós Rózsa, to step in. Rózsa concentrated on the climactic chase and epilogue, while Frank Skinner scored the early scenes. Rózsa later compiled a "Mark Hellinger Suite" of music from his three Hellinger pictures (including The Killers and Brute Force). The Naked City epilogue, "Song of a Great City," was Rózsa's tribute to the producer.[8]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The film was a considerable hit at the box office.[9]

Critical reception[]

Film critic Bosley Crowther, while having problems with the script, liked the location shooting and wrote "Thanks to the actuality filming of much of its action in New York, a definite parochial fascination is liberally assured all the way and the seams in a none-too-good whodunnit are rather cleverly concealed. And thanks to a final, cops-and-robbers "chase" through East Side Manhattan and on the Williamsburg Bridge, a generally talkative mystery story is whipped up to a roaring 'Hitchcock' end."[10]

In July 2018, it was selected to be screened in the Venice Classics section at the 75th Venice International Film Festival.[11]

Awards and honors[]

Wins

- Academy Awards: Oscar, Best Cinematography, Black-and-White, William H. Daniels; Best Film Editing, Paul Weatherwax; 1949.

Nominations

- Academy Awards: Oscar, Best Writing, Motion Picture Story, Malvin Wald; 1949.

- British Academy of Film and Television Arts: BAFTA Film Award, Best Film from any Source, USA; 1949.[12]

- Writers Guild of America: WGA Award (Screen), Best Written American Drama, Albert Maltz and Malvin Wald; The Robert Meltzer Award (Screenplay Dealing Most Ably with Problems of the American Scene), Albert Maltz and Malvin Wald; 1949.

Adaptations[]

The film was the inspiration for a half-hour television series of the same name, which used the film's famous concluding line. The characters of Muldoon and Halloran initially returned in the series, but they were now played by John McIntire and James Franciscus. The series ran for a single season in 1958 to 1959, earning an Emmy Award nomination as Best Drama. It was resurrected in Fall 1960 as an hour-long drama, which ran from October 1960 to September 1963.[13] The film was the direct inspiration for the case by the same name in the 2011 video game LA Noire. The case follows the plot of the film very closely, including the doctor’s name and alias being the same.

References[]

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1948", Variety, 5 January 1949, p. 46

- ^ Lewis and Smoodin, p. 379.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence. "Films Chosen For Registry." New York Times (December 28, 2007)

- ^ Wald, Maltz, and Bruccoli, p. 146.

- ^ Willett, p. 91; Eagan, p. 413; Spicer, p. 320.

- ^ Naremore, p. 281.

- ^ Park, p. 60.

- ^ See Rózsa's Double Life (1982, 1989) and Gergely Hubai, Torn Music: Rejected Film Scores (2012).

- ^ Variety (7 May 2018). "Variety (March 1948)". New York, NY: Variety Publishing Company. Retrieved 7 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley. "Naked City, Mark Hellinger's Final Film, at Capitol – Fitzgerald Heads Cast." New York Times. March 5, 1948. Accessed 2008-01-30.

- ^ "Biennale Cinema 2018, Venice Classics". labiennale.org. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ^ "Awards Database." The British Academy of Film and Television Arts. BAFTA.org. No date. Accessed 2012-02-11.

- ^ Newcomb, p. 1585-1586.

Bibliography[]

- Eagan, Daniel. America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York: Continuum, 2010.

- Krutnik, Frank. "Un-American" Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

- Lewis, Jon and Smoodin, Eric Loren. Looking Past the Screen: Case Studies in American Film History and Method. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2007.

- Naremore, James. More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2008.

- Newcomb, Horace. Encyclopedia of Television. Vol. 1. New York: CRC Press, 2004.

- Park, William. What Is Film Noir? Lewisburg, Pa.: Bucknell University Press, 2011.

- Sadoul, Georges and Morris, Peter. Dictionary of Films. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1972.

- Spicer, Andrew. Historical Dictionary of Film Noir. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2010.

- Wald, Marvin; Maltz, Albert; and Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph. The Naked City: A Screenplay. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 1948.

- Willett, Ralph. The Naked City: Urban Crime Fiction in the USA. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1996.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Naked City. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Naked City |

- The Naked City at IMDb

- The Naked City at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Naked City at the TCM Movie Database

- The Naked City at AllMovie

- The Naked City at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Naked City is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- 1948 films

- English-language films

- 1948 crime drama films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- American crime drama films

- American mystery films

- Culture of New York City

- Fictional portrayals of the New York City Police Department

- Film noir

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films directed by Jules Dassin

- Films scored by Miklós Rózsa

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in New York City

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- American police detective films

- 1940s police procedural films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films scored by Frank Skinner

- 1948 mystery films