The Opposite of Sex

| The Opposite of Sex | |

|---|---|

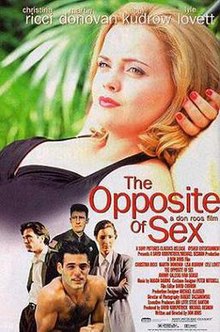

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Don Roos |

| Written by | Don Roos |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Hubert Taczanowski |

| Edited by | David Codron |

| Music by | Mason Daring |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million |

| Box office | $6.4 million[2] |

The Opposite of Sex is a 1998 American romantic comedy film written and directed by Don Roos, and starring Christina Ricci, Martin Donovan and Lisa Kudrow.[3] It marked the final film produced by Rysher Entertainment.

Plot[]

Sixteen-year-old Dedee Truitt (Christina Ricci) runs away from home. She is pregnant by her ex-boyfriend, Randy Cates (William Lee Scott). Not revealing her pregnancy, Dedee eventually moves in with her much older half-brother Bill (Martin Donovan), a gay teacher in a conservative, suburban community in Saint Joseph County, Indiana.

Although he is living with Matt (Ivan Sergei), Bill still mourns the loss of his previous partner, Tom, who died of AIDS some time ago. Bill maintains a friendship with Tom's younger sister, Lucia (Lisa Kudrow), who idolized her brother.

Dedee seduces Matt, then tricks him into believing he has impregnated her. They elope, leaving Bill and Lucia to track them down.

Bill and Lucia find Dedee and Matt in Los Angeles, only to discover Dedee has stolen Tom's ashes and is holding them for ransom. Randy also finds Dedee; they inform Matt that they are taking the ashes and moving away. They escape but soon get into an argument that leads to Dedee accidentally shooting Randy. She and Matt escape to Canada.

Lucia and Bill have a falling out after Lucia implies that Tom died as a result of having gay sex. Despondent, Lucia has a one-night stand with Sheriff Carl Tippett (Lyle Lovett) who had previously made unsuccessful romantic overtures to her. Lucia later discovers that she is pregnant.

Bill eventually tracks down Matt and Dedee. Dedee goes into labor and Bill accompanies her into the delivery room. After giving birth to her son, Dedee returns Tom's ashes to Bill, apologizing for her actions in the past year.

Dedee ends up serving time in prison, leaving her son in Bill's care while she's incarcerated. After a few months, she moves back in with Bill, while Matt goes traveling, and Lucia gives birth to her own child. Eventually, Dedee decides that her son would be better off with Bill, who is now dating Dedee's parole officer, and runs away.

Dedee sarcastically concludes that sex is precisely the opposite of what people should want, leading as it does to kids, disease or, worst of all, relationships. At the end of the film, the vignettes of the various caring relationships among the characters show the opposite of superficial sexual gratification.

Cast[]

- Christina Ricci as Dedee Truitt

- Ivan Sergei as Matt Mateo

- Martin Donovan as Bill Truitt

- Lisa Kudrow as Lucia De Lury

- Lyle Lovett as Carl Tippett

- William Lee Scott as Randy Cates

- Johnny Galecki as Jason Bock

- Colin Ferguson as Tom De Lury

- Megan Blake as Bobette

- Dan Bucatinsky as Timothy

- Chauncey Leopardi as Joe

- Rodney Eastman as Ty

- Heather Fairfield as Jennifer Oakes

- Leslie Grossman as Girl Student

Production[]

The Opposite of Sex was shot from June 1997 to July 1997 in Los Angeles, California.[4] It would end up being the last theatrical work produced by Rysher Entertainment, who shut down their film unit the same month that shooting wrapped.[5] Sony's arthouse division Sony Pictures Classics distributed the film.[4]

Reception[]

For its North American run, The Opposite of Sex took in film rentals of $5,881,367. The opening weekend saw a per screen average of $20,477 for the 5 theaters showing it.

Janet Maslin in The New York Times called it a "gleefully acerbic comedy". Christina Ricci's performance was widely praised and she received a nomination for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Comedy or Musical. Roger Ebert especially enjoyed the voice-over narration supplied in-character by Ricci, calling it "refreshing" and comparing it to Mystery Science Theater 3000:

When you've seen enough movies, alas, you can sense the gears laboriously turning, and you know with a sinking heart that there will be no surprises. The Dede character subverts those expectations; she shoots the legs out from under the movie with perfectly timed zingers. I hate people who talk during movies, but if she were sitting behind me in the theater, saying all of this stuff, I'd want her to keep right on talking.

On Rotten Tomatoes, 80% of 41 critics gave the film a positive review. The site's critics consensus reads: "The Opposite of Sex smartly lightens a bitter story with sharp insights and strong dialogue - as well as a startlingly mature performance from former child actor Christina Ricci."[6] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 70 out of 100, based on reviews from 26 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[7]

American Film Institute recognition nominated the film for its AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs list.[8]

Analysis[]

Director Don Roos has been noted for his depiction of sexual fluidity, which features in The Opposite of Sex as well as other Roos films such as Happy Endings.[9]

The film was criticized by Judith Kegan Gardiner in the book Masculinity Studies and Feminist Theory, describing The Opposite of Sex as representative of a "fairly repulsive genre of films" that feature a "heterosexual conversion narrative" that is "set in motion by the desire of a heterosexual person for a seemingly unattainable gay person."[10]

References[]

- ^ "The Opposite of Sex (18)". British Board of Film Classification. September 14, 1998. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ "The Opposite of Sex (1998) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (May 29, 1998). "The Opposite of Sex (1998) FILM REVIEW; Her Mouth Is Poison, and Her Heart Is Fool's Gold". The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Opposite of Sex". February 10, 1998.

- ^ "Rysher calls 'Cut!'". July 9, 1997.

- ^ "The Opposite of Sex (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Opposite of Sex". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs Nominees" (PDF). Afi.com. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Carr, David (May 8, 2005). "The Family Guy Behind the Dark Comedies". The New York Times. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ Gardiner, Judith Kegan (2002). Masculinity Studies and Feminist Theory. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 346. ISBN 9780231122795.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Opposite of Sex |

- 1998 films

- English-language films

- 1990s romantic comedy-drama films

- 1998 LGBT-related films

- American films

- American LGBT-related films

- American independent films

- Films shot in California

- Gay-related films

- Films directed by Don Roos

- Male bisexuality in film

- American pregnancy films

- Films with screenplays by Don Roos

- Films adapted into plays

- Hyperlink films

- Films scored by Mason Daring

- 1998 independent films

- American romantic comedy-drama films

- LGBT-related romantic comedy-drama films

- 1998 comedy films

- 1998 drama films

- 1990s pregnancy films