The Scarlet Empress

| The Scarlet Empress | |

|---|---|

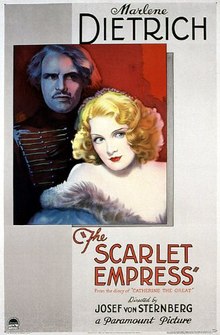

French film poster | |

| Directed by | Josef von Sternberg |

| Screenplay by | Manuel Komroff (diary arranger) Eleanor McGeary |

| Based on | the diary of Catherine the Great |

| Produced by | Emanuel Cohen Josef von Sternberg |

| Starring | Marlene Dietrich John Lodge Sam Jaffe Louise Dresser C. Aubrey Smith |

| Cinematography | Bert Glennon |

| Edited by | Josef von Sternberg Sam Winston |

| Music by | W. Franke Harling John Leipold |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $900,000[1] |

The Scarlet Empress is a 1934 American historical drama film starring Marlene Dietrich and John Lodge about the life of Catherine the Great. It was directed and produced by Josef von Sternberg from a screenplay by Eleanor McGeary, loosely based on the diary of Catherine arranged by Manuel Komroff.

Even though substantial historical liberties are taken, the film is viewed positively by modern critics.[2][3] The Scarlet Empress is particularly notable for its attentive lighting and the expressionist art design von Sternberg created for the Russian palace.

The film stars Dietrich as Catherine, supported by John Lodge, Sam Jaffe, Louise Dresser, and C. Aubrey Smith. Dietrich's daughter Maria Riva plays Catherine as a child.

Plot[]

Princess Sophia Frederica (Marlene Dietrich) is the innocent daughter of a minor East Prussian prince and an ambitious mother. She is brought to Russia by Count Alexei (John Lodge) at the behest of Empress Elizabeth (Louise Dresser) to marry her simple-minded nephew, Grand Duke Peter (Sam Jaffe). The overbearing Elizabeth renames her Catherine and repeatedly demands that the new bride produce a male heir to the throne, which is impossible, because Peter never comes near her after their wedding night. He spends all his time with his mistress or his toy soldiers or his live soldiers. Alexei pursues Catherine relentlessly, but has no success after a literal roll in the hay a week after her wedding. At dinner, he tries to pass a note to Catherine, begging for a few precious seconds with her, but Elizabeth intercepts it. She warns Catherine that Alexei is a womanizing heartbreaker.

That night, Elizabeth sends Catherine down a secret stair to open the door for a lover, warning her to not let him see her. Catherine sees the man is Alexei and, shaken and angry, hurls a miniature he gave her out the window. She then goes out into the garden to retrieve it and is stopped by a handsome Lieutenant. He is on guard duty for the first time, and, when she tells him who she is, he initially does not believe her and begins to flirt. Suddenly, she throws her arms around his neck. They kiss, and she surrenders. Months later, all of Russia, with the exception of Peter, celebrates as Catherine gives birth to a son. Elizabeth promptly takes over the boy's care and sends the exhausted Catherine a magnificent necklace.

Elizabeth's health takes a turn for the worse. Peter plans to remove Catherine from court, perhaps by killing her. However, Catherine has become a very different woman, one who is self-assured, sensual, and cynical. She has learned how things work in Russia and plans to stick around. The Archimandrite is worried by the thought of Peter on the throne and offers Catherine his help, but she demurs, saying she has "weapons that are far more powerful than any political machine." Catherine is playing blind man's bluff with her ladies in waiting, lavishing kisses on the assembled soldiers, when the bells toll for Elizabeth's passing. Peter taunts Elizabeth's corpse as she lies in state, saying it is now his turn to rule.

An intertitle reads: "And while his Imperial Majesty Peter the III terrorized Russia, Catherine coolly added the army to her list of conquests." She inspects the officers of Alexei's pet regiment, singling out Lieutenant Dmitri (the man from the garden) by borrowing one of Alexei's decorations to reward him "for bravery in action." Orlov, Dmitri's Captain, also attracts her attention. That evening, Catherine, who had refused to see Alexi privately since she admitted him to Elizabeth's quarters, finally lets him visit her. When they are alone in her bedroom, she toys with him before sending him down the secret stair to open the door for the man waiting there. He sees Captain Orlov and understands his chance to have a relationship with Catherine has passed.

At dinner, the Archimandrite collects alms for the poor: Catherine strips her arm of bracelets, Orlov donates a handful of gems, Alexei gives a purse full of coins, the Chancellor adds a single coin, and Peter's mistress puts a scrap of food on the plate. Peter just slaps the Archimandrite's face and says "There are no poor in Russia!" He then proposes a toast to his mistress, but Catherine refuses to participate. Peter calls her a fool and she leaves with Orlov. Peter cashiers Orlov and puts Catherine under house arrest. He issues a public proclamation that she is dying.

In the middle of the night, Orlov sneaks into Catherine's room and wakens her. In uniform, she flees the palace with her loyal troops. Alexei sees her go and murmurs: "Exit Peter the Third, Enter Catherine the Second." She rides through the night, gathering men to her cause. In the cathedral, the Archimandrite blesses Catherine and she rings the bell that signals the start of the coup. Peter awakens and opens his door, finding Orlov standing "guard". Orlov tells him "There is no emperor. There is only an empress." and kills him. Catherine and her troops ride up the stairs in the palace, thundering into the throne room as pealing bells are joined by the 1812 Overture.

Cast (in credits order)[]

- Marlene Dietrich as Princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg, later Empress Catherine II

- John Lodge as Count Alexey Razumovsky

- Sam Jaffe (in his film debut) as Grand Duke Peter, later Emperor Peter III

- Louise Dresser as Empress Elizaveta Petrovna

- C. Aubrey Smith as Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, father of Catherine

- Gavin Gordon as Captain Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov

- Olive Tell as Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp, mother of Catherine

- Ruthelma Stevens as Elizaveta Vorontsova, mistress of Peter III

- Davison Clark as Archimandrite Simeon Todorsky / Arch-Episcopope

- Erville Alderson as Chancellor Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin

- Philip Sleeman as Jean Armand de Lestocq, the court physician

- Marie Wells as Marie Tshoglokof, one of Catherine's ladies-in-waiting

- Hans Heinrich von Twardowski as Ivan Shuvalov, Empress Elizabeth's paramour

- Gerald Fielding as Lieutenant Dimitri

- Maria Riva as Sophia (as a child)

Style[]

Josef von Sternberg described The Scarlet Empress as "a relentless excursion into style".[4] Historical accuracy is sacrificed for the sake of "a visual splendor verging on madness".[5] To show Russia as backward, anachronistic, and in need of reform, the imperial court was set at the Moscow Kremlin, rather than in Saint Petersburg, which was a more Europeanized city.[6] The royal palaces are represented as made of wood and full of religious sculptures (in fact, there is no free-standing religious sculpture in the Orthodox tradition). Pete Babusch from Switzerland created hundreds of gargoyle-like sculptures of male figures "crying, screaming, or in throes of misery" which "line the hallways, decorate the royal thrones, and even appear on serving dishes".[7] This resulted in "the most extreme of all of the cinematic representations of Russia".[6] In film critic Robin Wood's words:

"A hyperrealist atmosphere of nightmare with its gargoyles, its grotesque figures twisted into agonized contortions, its enormous doors that require a half-dozen women to close or open, its dark spaces and ominous shadows created by the flickerings of innumerable candles, its skeleton presiding over the royal wedding banquet table."[8]

The Scarlet Empress was one of the later mainstream Hollywood motion pictures to be released before the Hays Code was strictly enforced. Near the beginning of the film, young Sophia's tutor reads to her about “Peter the Great and Ivan the Terrible and other Russian Czars and Czarinas who were hangmen,” introducing a nightmarish and disturbingly explicit montage of tortures and executions that includes several brief shots of women with exposed breasts.

Reception[]

New York Times reviewer Dave Kehr described the film, with its "metaphysical treatment" of the subject, as clearly superior to the contemporaneous The Rise of Catherine the Great (1934), which was directed by Paul Czinner and produced by Alexander Korda.[9]

Leonard Maltin gives the picture three out of four stars: “Von Sternberg tells the story...in uniquely ornate fashion, with stunning lighting and camerawork and fiery Russian music. It's a visual orgy; dramatically uneven, but cinematically fascinating.”[10]

In 1998, Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader included the film in his unranked list of the best American films not included on the AFI Top 100.[11]

In a 2001 review of the film for the Criterion Collection, film scholar Robin Wood placed it in the context of the collaboration between Sternberg and Dietrich:

“The connecting theme of all the von Sternberg/Dietrich films might be expressed as a question: How does a woman, and at what cost, assert herself within an overwhelmingly male-dominated world? Each film offers a somewhat different answer (but none very encouraging), steadily evolving into the extreme pessimism and bitterness of The Scarlet Empress and achieving its apotheosis in their final collaboration The Devil Is a Woman. This resulted in the (today extraordinary) misreading of the films (starting from The Blue Angel) as “films about a woman who destroys men.” Indeed, one might assert that it is only with the advent of radical feminism that the films (and especially the last two) have become intelligible”.[12]

The Guardian's historical films reviewer Alex von Tunzelmann credits the film with "racy" entertainment value (grade: "B"), but she severely discredits its historical depth and accuracy (grade: "D−"), giving the film historical credence only for creating a "vaguely accurate impression" of Catherine's relationship with Peter, dismissing the rest as stemming from the director's fantasies and infatuations.[13]

References[]

- ^ Box office / business for The Scarlet Empress (1934) at IMDB

- ^ Roger Ebert, The Scarlet Empress Review, January 16, 2005.

- ^ Derek Malcolm, Josef von Sternberg: The Scarlet Empress, May 25, 2000, The Guardian.

- ^ Josef Von Sternberg. Fun in a Chinese Laundry. Mercury House, 1988. P. 265.

- ^ Charles Silver. Marlene Dietrich. Pyramid Publications, 1974. P. 51.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berger, Stefan; Lorenz, Chris; Melman, Billie (21 August 2012). Popularizing National Pasts: 1800 to the Present. Routledge. ISBN 9781136592881. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Leonard, Suzanne; Tasker, Yvonne (20 November 2014). Fifty Hollywood Directors. Routledge. ISBN 9781317593935. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Robin Wood. "The Scarlet Empress". The Criterion Collection Online Cinematheque.

- ^ Dave Kehr, "Alexander Korda’s Historical Films Hold a Fun House Mirror Up to the Present," May 6, 2009, New York Times, retrieved February 20, 2020

- ^ "The Scarlet Empress (1934) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 25, 1998). "List-o-Mania: Or, How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love American Movies". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020.

- ^ Wood, Robin. "The Scarlet Empress". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- ^ von Tunzelmann, Alex "Reel history: The Scarlet Empress (1934)...This week: peasants on iron maidens and equine erotica in a biopic of Catherine the Great," July 14, 2008, The Guardian, retrieved February 20, 2020

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Scarlet Empress. |

- The Scarlet Empress at IMDb

- The Scarlet Empress at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Scarlet Empress at AllMovie

- The Scarlet Empress at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Scarlet Empress at the TCM Movie Database

- The Scarlet Empress an essay by Robin Wood at the Criterion Collection

- 1934 films

- English-language films

- 1930s historical drama films

- 1930s biographical drama films

- American films

- American historical drama films

- American biographical drama films

- American black-and-white films

- Films about Catherine the Great

- Films set in Russia

- Films set in Germany

- Films set in the 18th century

- Films directed by Josef von Sternberg

- Works based on diaries

- 1934 drama films