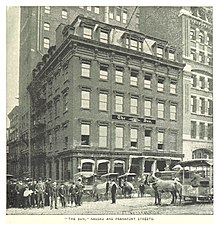

The Sun (New York City)

| It Shines for All | |

| |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid[1] |

| Owner(s) | Frank Munsey (1916) |

| Editor | Benjamin Day (1833) |

| Founded | September 3, 1833 |

| Ceased publication | January 4, 1950 |

| Relaunched | The New York Sun (2002) |

| Headquarters | New York City |

The Sun was a New York newspaper published from 1833 until 1950. It was considered a serious paper,[2] like the city's two more successful broadsheets, The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune.

History[]

In New York, The Sun began publication September 3, 1833, as a morning newspaper edited by Benjamin Day (1810–1889), with the slogan "It Shines for All".[3] It only cost one penny (equivalent to 27¢ in 2020), was easy to carry, and its illustrations and crime reporting were popular with working-class readers. It inspired a new genre across the nation in various cities which followed known as the penny press making the news more available to lower-income readers at a cheaper price when most papers cost five cents to purchase.[1]

The Sun was the first newspaper to report crimes and personal events such as suicides, deaths, and divorces. Day printed the first newspaper account of a suicide. This story was significant because it was the first about an ordinary person. It changed journalism forever, making the newspaper an integral part of the community and the lives of the readers. Prior to this, all stories in newspapers were about politics or reviews of books or the theater. Day was the first to hire reporters to go out and collect stories. Prior to this, newspapers relied on readers sending in items, and on reprinting making unauthorized copies of stories from other newspapers in the days before the organization of syndicates like the Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI). The Sun's focus on crime is the beginning of "the craft of reporting and storytelling". If not the inventor, The Sun was nonetheless the newspaper which demonstrated conclusively that a newspaper could be substantially supported by advertisements and not subscription fees, and could be sold on the street instead of delivered to each subscriber. In addition, The Sun was aimed not at the elite but at the common masses of working people. Day and The Sun recognized that the masses were fast becoming literate, and demonstrated that a profit could be made selling to the larger numbers of them. Prior to The Sun, printers produced the newspapers, often at a loss, making their living selling printing services.[5]

An evening edition was introduced in 1887 known as The Evening Sun.

The newspaper magnate Frank Munsey bought both editions in 1916 and merged The Evening Sun with his New York Press. The morning edition of The Sun was merged for a time with Munsey's New York Herald as The Sun and New York Herald, but in 1920, Munsey separated them again, killed The Evening Sun, and switched The Sun to an evening publishing format.[3]

In 1917, The Sun moved its offices to the historic A.T. Stewart Company Building, site of America's first department store, at 280 Broadway between Chambers and Reade streets, renaming it "The Sun Building" with a landmark clock featuring its name and slogan on the Broadway façade.

Munsey died in 1925. He left the bulk of his estate, including The Sun, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The next year The Sun was sold to William Dewart, a longtime associate of Munsey's. His son Thomas later ran the paper.[6]

It continued until January 4, 1950, when it merged with the New York World-Telegram to form a new paper called the New York World-Telegram and Sun for 16 years; in 1966, this paper joined with the New York Herald Tribune to briefly become part of the World Journal Tribune preserving the names of three of the most historic city newspapers, which folded amid disagreements with the labor union the following year.

Milestones[]

The Sun first gained notice for its central role in the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, a fabricated story of life and civilization on the Moon which the paper falsely attributed to British astronomer John Herschel and never retracted.[7] On April 13, 1844, The Sun published as factual a story by Edgar Allan Poe now known as "The Balloon-Hoax", retracted two days after publication. The story told of an imagined Atlantic crossing by hot-air balloon.[8]

Today, the paper is best known for the 1897 editorial "Is There a Santa Claus?" (commonly referred to as "Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus"), written by Francis Pharcellus Church.[9]

John B. Bogart, city editor of The Sun between 1873 and 1890, made what is perhaps the most frequently quoted definition of the journalistic endeavor: "When a dog bites a man, that is not news, because it happens so often. But if a man bites a dog, that is news."[10] (The quotation is frequently attributed to Charles Dana, The Sun editor and part-owner between 1868 and his death in 1897.)

In 1926, The Sun published a review by John Grierson of Robert Flaherty's film Moana, in which Grierson said the film had "documentary value." This is considered the origin of the term "documentary film"[11]

The newspaper's editorial cartoonist, Rube Goldberg, received the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning for his cartoon, "Peace Today". In 1949, The Sun won the Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting for a groundbreaking series of articles by Malcolm Johnson, "Crime on the Waterfront". The series served as the basis for the 1954 movie On the Waterfront.

The Sun's first female reporter was , hired in 1868. Eleanor Hoyt Brainerd was hired as a reporter and fashion editor in the 1880s. Brainerd was one of the first women to become a professional editor, and perhaps the first full-time fashion editor in American newspaper history.

Legacy[]

The film Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) is a story about the death of a New York newspaper called The Day, loosely based upon the old New York Sun, which closed in 1950. The original Sun newspaper was edited by Benjamin Day, making the film's newspaper name a play on words (not to be confused with the real-life New London, Connecticut newspaper of the same name).

The masthead of the original Sun is visible in a montage of newspaper clippings in a scene of the 1972 film The Godfather. The newspaper's offices were a converted department store at 280 Broadway, between Chambers and Reade streets in lower Manhattan, now known as "The Sun Building" and famous for the clocks that bear the newspaper's masthead and motto. They were recognized as a New York City landmark in 1986.

In the 1994 movie The Paper, a fictional tabloid newspaper based in New York City bore the same name and motto of The Sun, with a slightly different masthead.

In 2002, a new broadsheet was launched, styled The New York Sun, and bearing the old newspaper's masthead and motto. It was intended as a "conservative alternative" and local-news focused alternative to the more liberal/progressive The New York Times and other New York newspapers. It was published by Ronald Weintraub and edited by Seth Lipsky, and ceased publication on September 30, 2008.[citation needed]

Journalists at The Sun[]

- John A. Arneaux, reporter in 1884

- Moses Yale Beach, an early owner of The Sun

- Paul Dana, editor, 1880–1897

- W. C. Heinz, war correspondent, sportswriter 1937–1950

- Bruno Lessing, reporter, 1888–1894

- Chester Sanders Lord, journalist and managing editor,[12] 1873-1913

- Kenneth M. Swezey, radio/technology reporter, 1930s

- John Swinton, chief editorialist, 1875–1883 and 1892–1897

See also[]

- List of defunct American periodicals

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rogers, Tony (March 17, 2017). "What's the Difference Between Broadsheet and Tabloid Newspapers?". ThoughtCo.

- ^ "Obituary of Charles Anderson Dana". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. October 27, 1897. p. 4. ISSN 2379-7304. Retrieved July 14, 2020 – via National Endowment for the Humanities.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sun's Centary". Time. September 11, 1933. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ O'Brien, Frank Michael. The Story of the Sun: New York, 1833–1918. New York: George H. Doran Co, 1918. p. 229

- ^ Spencer, David R.; Overholser, Geneva (January 23, 2007). The Yellow Journalism: The Press and America's Emergence as a World Power. Medill Vision of the American Press. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. pp. 22–28. ISBN 978-0-8101-2331-1.

- ^ "Thomas Dewart, 90,; Publisher of the Sun". The New York Times. September 5, 2001.

- ^ Washam, Erik, "Cosmic Errors: Martians Build Canals!" Archived September 12, 2012, at archive.today, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9. p. 410

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph. 110 Years Ago in News History: ‘Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus’ Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. American University. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, 16th edition, ed. Justin Kaplan (Boston, London, and Toronto: Little, Brown, 1992), p. 554.

- ^ Barsam, Richard (1992). Non-Fiction Film: A Critical History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20706-7.

- ^ The Young Man and Journalism, McGraw Hill, 1922.

Further reading[]

- Lancaster, Paul. Gentleman of the Press: The Life and Times of an Early Reporter, Julian Ralph of the Sun. Syracuse University Press; 1992.

- O'Brien, Frank Michael. The Story of The Sun: New York, 1833–1918 (1918) (page images and OCR)

- Steele, Janet E. The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana (Syracuse University Press, 1993)

- Stone, Candace. Dana and the Sun (Dodd, Mead, 1938)

- Tucher, Andie, Froth and Scum: Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and the Ax Murder in America's First Mass Medium'. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Sun (New York City). |

- The Sun digitized at Chronicling America, Library of Congress (1859 to 1916, incomplete)

- 1833 establishments in New York (state)

- 1950 disestablishments in New York (state)

- American penny papers

- Defunct newspapers published in New York City

- Publications disestablished in 1950

- Publications established in 1833

- Daily newspapers published in New York City