The Tales of Ensign Stål

The Tales of Ensign Stål (Swedish original title: Fänrik Ståls sägner, Finnish: Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat, or year 2007 translation Vänrikki Stålin tarinat) is an epic poem written in Swedish by the Finland-Swedish author Johan Ludvig Runeberg, the national poet of Finland. The poem describes the events of the Finnish War (1808–1809) in which Sweden lost its eastern territories;[1] these would become incorporated into the Russian Empire as the Grand Duchy of Finland.

Description[]

The first part of Ensign Stål was first published in the revolutionary year 1848, the second in 1860.[2][3][4] It shaped Finnish identity and was later given out free during the Winter War to raise patriotic spirit.[3] The first chapter of the poem also became the national anthem of Finland.[2]

The name of the title character, "Stål", is Swedish for steel, a typical example of a so-called "soldier's name". These were names, often consisting of simple words for traits or traits related to the military or nature, given to Swedish soldiers by their commanders, and many of Runeberg's characters have them: Dufva, Svärd and Hurtig ('pigeon', 'sword' and 'quick') are other examples

The poems of Ensign Stål feature several officers who fought in the Finnish War, including marshals Wilhelm Mauritz Klingspor and Johan August Sandels, generals , Carl Johan Adlercreutz, and Georg Carl von Döbeln, and Colonel Otto von Fieandt.[3]

Among the most famous characters is the simple but heroic rotesoldat Sven Dufva.[5] The organisations Lotta Svärd and the Swedish Women's Voluntary Defence Organization ("Lottorna") were named after the character in the poem of the same name.[6][7][8][9]

From its publication to the mid-twentieth Century, The Tales of Ensign Stål was staple reading in both Finnish and Swedish schools.[10] It shaped the later image of the war and of some of its real-life protagonists. Admiral Carl Olof Cronstedt is mainly remembered today for his treacherous surrender of the fortress of Sveaborg. The Russian general Yakov Kulnev, on the other hand, is described positively as a chivalrous and brave soldier and ladies' man.

Ensign Stål was translated into Finnish by a group led by fennoman professor Julius Krohn in 1867. Later translations were made by Paavo Cajander in 1889 and Otto Manninen 1909. Albert Edelfelt drew the illustrations between 1894–1900. Due to the dated language,[11] a new translation was issued in 2007. It raised some controversy, in particular due to the new wording of the poem Vårt Land, the national anthem of Finland.

Gallery[]

Ensign Stål and the undergraduate, Robert Wilhelm Ekman, 1853

"Dictate he begins of Duncker...", Albert Edelfelt, 1898-1900

Ensign Stål, Albert Edelfelt, 1898

The Croft Girl, Ville Vallgren, 1882

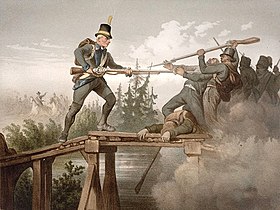

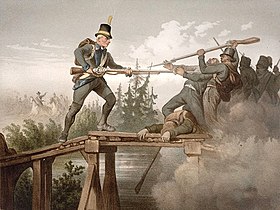

Sven Dufva and the Battle of Koljonvirta by Carl Staaff

Wounded Warrior in the Snow, Helene Schjerfbeck, 1880, the scene not directly from any poem but influenced by them[12]

March of the Pori Regiment, Albert Edelfelt, 1892

The Death of Wilhelm von Schwerin, Helene Schjerfbeck, 1886

The Death of Wilhelm von Schwerin, Albert Edelfelt, 1900

Governor (Maaherra), Albert Edelfelt, 1899

See also[]

- Gustaf Adolf Montgomery

- Sven Tuuva the Hero, a 1958 film based on the Sven Dufva poem

References[]

- ^ "Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat". Koppa. University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lindfors, Jukka (4 February 2020). "Vänrikki Stoolin tarinoita". Yle. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Vänrikki Stoolin henkilöhahmojen elämäkerrat Kansallisbiografiassa". Finlit. Finnish Literature Society. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Ekholm, Kai. "Vänrikki Stoolin tarinoita juuttui tulliin". Sananvapauteen. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Ylioppilastutkintolautakunta. "Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat eurooppalaisuuden ilmentäjänä". Mikko Porvali. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Perälä, Reijo (22 November 2019). "Lotta Svärd antoi nimensä Suomen maanpuolustusnaisille". Yle. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "13. Mistä nimi Lotta Svärd tulee?". Lotta Svärd. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Esteri (5 February 2019). "Runeberg, Lotta ja Svärd". Nostalgiset Naiset. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Järjestön historiallinen tausta". Koulukino. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Kaukonen, Erkka. "Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat patrioottisena propagandana" (PDF). Jultika. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Haapala, Riina (14 June 2018). "Vänrikki Stoolin tarinoiden esikuva vetää väkeä Kuruun – täällä Runeberg ja vänrikki Polviander kalastivat ja juopottelivat". Tamperelainen. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Kuvitukset". Runeberg.net. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Tales of Ensign Stål. |

- 1883 Swedish text of the book, with illustrations, at Project Runeberg.

- 1927 Swedish text of the book, with modernized spelling, at Project Runeberg.

- Epic poems

- Finnish literature

- Swedish-language literature

- Finnish War

- 1848 poems

- 1860 poems