The Trial of Billy Jack

| The Trial of Billy Jack | |

|---|---|

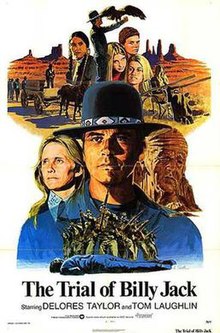

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tom Laughlin |

| Written by | Frank Christina Teresa Christina (pen names for Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor) |

| Produced by | Joe Cramer |

| Starring | Delores Taylor Tom Laughlin |

| Cinematography | Jack A. Marta |

| Edited by | Michael Economou George Grenville Michael Kahn Michael Karr Jules Nayfack Tom Rolf Toni Rolf |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Taylor-Laughlin |

Release date |

|

Running time | 170 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.5 million[1] |

The Trial of Billy Jack is a 1974 Western action film starring Delores Taylor and Tom Laughlin. It is the sequel to the 1971 film Billy Jack and the third film overall in the series.[2]

Directed by Laughlin, the film has a running time of nearly three hours. Although commercially successful, it was panned by critics. The film was included in the book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time.[3]

Plot[]

Billy Jack goes to court facing an involuntary manslaughter charge stemming from events in the earlier film. He is found guilty and sentenced to a prison term. Meanwhile, the kids at the Freedom School—an experimental school for runaways and troubled youth on a Native American reservation in Arizona—vow to rebuild the school. They raise funds and acquire a new building, eventually starting their own newspaper and television station.

Inspired by Nader's Raiders, they begin using the newspaper and TV station to conduct investigative reporting, angering several politicians and townspeople in the process with their exposés.

The school's activities range from having their own search and rescue team to artistic endeavors such as a marching band and belly dancing. The school hosts a large marching-band contest and arts festival, called "1984 Is Closer Than You Think," to raise money for the school.

Billy Jack is released from prison and, trying to reconnect with his spiritual beliefs, begins a series of lengthy vision quests. He becomes involved in a radical group on the reservation that opposes the federal effort to cease recognition of their tribe and the surrender of their tribal lands to local developers. When one of the tribal members is arrested for poaching deer on what was formerly tribal land, the school comes to his defense.

The school begins to hold hearings on the rights of the native people and child abuse. The school defies a court order to return a boy to his father who had abused the boy and cut off his hand. The FBI begins visiting the school and taps their phones.

As tensions mount between the school and the people in the nearby town, a mysterious explosion at the school knocks their television station off the air. The governor calls a state of emergency and mobilizes the National Guard, and a curfew is established in town. The students respond by holding a parade in the town in violation of the curfew. On the way back to the school, their bus breaks down and local townspeople confront the students and threaten to set their bus on fire.

Billy Jack appears during the incident to protect the students and then comes to the attempted rescue of a tribal member who is being harassed and beaten to death at a local dance in town. Billy managed to use his Karate on Posner, who gets killed by the kick to the throat. However, The National Guard is stationed around the school and is ordered to open fire on the students, killing four and wounding hundreds more.

The entire story is told through flashbacks by teacher Jean Roberts from her hospital bed after the shooting. During Billy's trial, he mentions the 1968 My Lai massacre and recalls, in a flashback scene, witnessing a similar incident while serving in Vietnam.

Cast[]

- Tom Laughlin as Billy Jack

- Delores Taylor as Jean Roberts

- Victor Izay as Doc

- Teresa Kelly as Carol

- Sara Lane as Russell

- Geo Anne Sosa as Joanne

- Lynn Baker as Lynn

- Riley Hill as Posner

- Sparky Watt as Sheriff Cole

- Gus Greymountain as Blue Elk

- Sacheen Littlefeather as Patsy Littlejohn

- Michael Bolland as Danny

- Jack Stanley as Grandfather

- Bong-Soo Han as Master Han

- Rolling Thunder as Thunder Mountain

- William Wellman Jr. as National Guardsman

Production[]

Part of the film was shot in Monument Valley in Utah.[4]

Release[]

The film opened on November 13, 1974 in one of the widest releases of the time. It opened in an additional 150 theaters two days later, totaling more than 1,000 theaters in its opening week, including 180 four wall distribution locations in New York, Philadelphia and Phoenix. The wide release was accompanied by a $3 million advertising campaign in the opening week.[1]

Reception[]

Box office[]

In its opening five days, the film grossed $9 million and was number one at the U.S. box office, where it remained for three weeks.[1][5] By 1976 the film had earned $6,716,000 in theatrical rentals in the United States and Canada.[6] Its international take was very small; Laughlin suggested that American government agencies conspired to force the film to be "banned in almost every country in the world" to hide its "scorching exposés" from foreign audiences, though he admitted that he had no supporting evidence.[7][8]

Critical[]

The film was a commercial success upon its release in theaters, but met with a harsh reaction from critics.[3][9]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it "three hours of naiveté merchandised and marketed with the not-so-innocent vengeance that I associate with religious movements that take leases on places like the Houston Astrodome."[9]

Variety wrote that the film was "badly in need of trimming its 170-minutes running time" and that Laughlin sometimes seemed to be "only a visiting guest star, since he does not figure in what seems to be reels of irrelevant school action. It is only when he is on-camera that the picture picks up, a commanding figure whose low-key characterization adds to the brilliance of his performance."[10]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film one star out of four and called it "gross, misleading and a run-on bore," writing that "whereas the original had moments of genuine humor and refreshing improvisation, 'The Trial of Billy Jack' comes on as totally committed to establishing half-truths. In reality, both My Lai and Kent State are testaments to the danger of arming young men and placing them in combat situations. But 'The Trial of Billy Jack' twists those facts so as to make the killings a direct policy statement of the national government."[11]

Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times described the film as "one of the longest, slowest, most pretentious and self-congratulatory ego trips ever put to film. The running time is an excruciating three hours, which make you wonder what the five count 'em five credited editors did for their pay."[12]

Gary Arnold of The Washington Post called it "such a rambling, maudlin, sanctimonious rehash of its phenomenally successful predecessor that one can at least hope for a few defections among the legions of young fans who evidently thrilled to the self-flattering gospel according to 'Billy Jack,'" concluding, "Laughlin's point of view may be militantly liberal, but his artistic methods are reactionary in the extreme."[13]

Pauline Kael of The New Yorker declared, "This film probably represents the most extraordinary display of sanctimonious self-aggrandizement the screen has ever known."[14]

Donald J. Mayerson wrote in Cue that "this sequel proved more of a trial for me than it was for Billy."[3] Leonard Maltin's film guide assigned its lowest possible grade of BOMB and called the film "Laughable" until the final massacre scene that rendered its peaceful message "ludicrous."[15]

In a retrospective review, Donald Guarisco of AllMovie wrote: "Ultimately, most viewers are likely to be baffled by The Trial of Billy Jack, and it can only be recommended to B-movie fans with a hearty constitution...it's a mess, but it's a fascinating mess."[16]

When the film was reissued for another theatrical run in the spring of 1975, an accompanying newspaper ad campaign attacked critics as being out of touch with the tastes of mass audiences.[17][18]

Despite its initial commercial success, the film marked the effective end of success for the Billy Jack series.[citation needed] It was followed by Billy Jack Goes to Washington in 1977, which never saw widespread theatrical release. A fifth film, The Return of Billy Jack, filmed in 1985-86, was never completed and remains unreleased. The Trial of Billy Jack was included among the selections in the 1978 book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time.[3]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Albarino, Richard (November 20, 1974). "'Billy' Sequel's Grand $11-Mil Preem". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ Waxman, Sharon (June 20, 2005). "Billy Jack Is Ready to Fight the Good Fight Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-07-03. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Medved, Harry; Dreyfuss, Randy (1978). The Fifty Worst Films Of All Time. Popular Library. pp. 255–256. ISBN 0-445-04139-0.

- ^ D'Arc, James V. (2010). When Hollywood came to town: a history of moviemaking in Utah (1st ed.). Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. ISBN 9781423605874.

- ^ "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. November 27, 1974. p. 9.

- ^ "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. 7 January 1976. p. 44.

- ^ Medved and Dreyfuss, p. 260.

- ^ "The Trial of Billy Jack - History". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Canby, Vincent (November 14, 1974). "Screen: 'Trial of Billy Jack,' a Sequel". The New York Times: 58. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "Film Reviews: The Trial Of Billy Jack". Variety. November 13, 1974. 18.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (November 25, 1974). "Trial of Billy Jack". Chicago Tribune. Section 4, p. 17.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (November 13, 1974). "A 'Billy Jack' Marathon". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (November 15, 1974). "The Trial of Billy Jack" The Washington Post. B1, B13.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (November 25, 1974). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 180.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard, ed. (1995). Leonard Maltin's 1996 Movie & Video Guide. Signet. p. 1370. ISBN 0-451-18505-6.

- ^ Guarisco, Donald. "The Trial of Billy Jack". AllMovie. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "'Billy Jack' vs. Critics". Variety. April 30, 1975. p. 5.

- ^ "'Jack' Again Using Anti-Critic Ads". Variety. May 21, 1975. p. 7.

External links[]

- 1974 films

- English-language films

- 1970s action drama films

- Films set in Arizona

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films about Native Americans

- Hippie films

- American political drama films

- American sequel films

- American films

- Hapkido films

- Films scored by Elmer Bernstein

- Films directed by Tom Laughlin

- Films shot in Utah

- 1974 drama films