The Two Jakes

| The Two Jakes | |

|---|---|

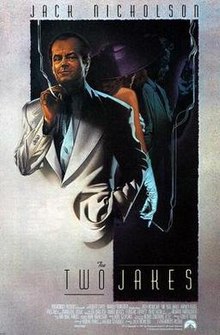

Theatrical release poster by Robert Rodriguez[1] | |

| Directed by | Jack Nicholson |

| Written by | Robert Towne |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Vilmos Zsigmond |

| Edited by | Anne Goursaud |

| Music by | Van Dyke Parks |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[2] |

| Box office | $10 million[3] |

The Two Jakes is a 1990 American neo-noir mystery film and the sequel to the 1974 film Chinatown.[4] Directed by and starring Jack Nicholson, it also features Harvey Keitel, Meg Tilly, Madeleine Stowe, Richard Farnsworth, Frederic Forrest, David Keith, Rubén Blades, Tracey Walter and Eli Wallach. Reprising their roles from Chinatown are Joe Mantell, Perry Lopez, James Hong, and, in a brief voice-over, Faye Dunaway. The character of Katherine Mulwray returns as well, played by Tilly. The musical score for the film is by Van Dyke Parks, who also appears as a prosecuting attorney. The screenplay is by Robert Towne, whose script for Chinatown won an Academy Award.

The Two Jakes faced a troubled production and went through several years of development hell. Various actors were attached at several points, including Joe Pesci and Roy Scheider, with screenwriter Towne also at one point set to direct and producer Evans set to co-star. Filming finally took place with Nicholson at the helm, filming around Los Angeles in the early summer of 1989. The film was released by Paramount Pictures on August 10, 1990. The film received mixed reviews and was not a box office success and plans for a third film about J. J. Gittes, with him near the end of his life, were abandoned.

Plot[]

In 1948 Los Angeles, businessman Julius "Jake" Berman hires seasoned private investigator J. J. "Jake" Gittes to catch his wife, Kitty, committing adultery. During the sting, Berman unexpectedly kills his wife's lover, Mark Bodine, who is also his partner in a real estate development company. Gittes, unaware of this, suddenly finds himself being scrutinized for his role in what appears to be a premeditated murder; the key piece of evidence is the wire recording that Gittes set up. It audio taped the illicit encounter, the confrontation, and Bodine being killed. However, the audio makes it unclear whether Berman intended to kill Bodine before confronting him, making it murder, or if the killing was a spontaneous act of jealousy, possibly qualifying as "temporary insanity," which is a defense of murder.

Gittes is forced to convince his old acquaintance, LAPD Captain Lou Escobar, that he should not be charged as an accomplice. Oddly, Berman seems unconcerned that he may be charged with murder. Gittes has the recording, which Berman's attorney, Cotton Weinberger, and mobster friend Mickey Nice, both want and is locked in a safe in Gittes L.A. office.

Recent earthquakes have recently rocked the area, including Berman's housing development in the Valley. Gittes is nearly killed in a gas explosion, waking to find Berman and Kitty standing over him.

Gittes has a confrontation, and a later sexual encounter, with Lilian Bodine, the dead man's angry widow. He is presented with proof that Earl Rawley, a wealthy and ruthless oil man, may be drilling under the Bodine and Berman development, though Rawley denies doing so. Gittes focuses his attention on determining who owns the mineral rights to the land. Gittes eventually discovers the rights are owned by Katherine Mulwray, daughter of the late Evelyn Mulwray, his love interest from eleven years prior. He also discovers that the deed transfers were executed in a manner to attempt to hide Katherine Mulwray's prior ownership and continued claim of the mineral rights. Furthermore, he also discovers that Katherine's father (and grandfather) Noah Cross, has since died and left her all his financial assets.

Gittes receives word from his associates that Berman has been seen with a blond woman, along with Mickey and a bodyguard. Gittes determines that the woman is an oncologist and is treating Berman for cancer. Gittes confronts Berman with this knowledge and gets a full confession: his cancer is terminal and will die soon. He has taken steps to ensure that Kitty will be financially secure once he dies.

To persuade Kitty to talk to him, Gittes works to prove that her husband did set out to kill his partner. Once accomplished, Kitty agrees to meet Gittes and tell him what she knows about Berman. In the process of discussing Berman's possible motivations, mineral rights, and the possible whereabouts of Katherine, it is revealed that Kitty and Katherine are the same person. Kitty reveals that she never suspected that her husband was dying.

Gittes holds onto the recording, refusing to let anyone hear it until the inquest. Gittes edits the recording, omitting Kitty's name and making other alterations to indicate Bodine's death was not premeditated. The court quickly drops all charges against Berman. Realizing Gittes is aware of his terminal illness and knowing the model house he is in is filling with natural gas, Berman asks Gittes and Mickey to leave so he can "have a smoke." As they drive off, the house explodes. With no remains left to recover, the police make no attempt to investigate his death and Kitty inherits a substantial sum from her late husband.

The story ends with Kitty and Gittes in his office. They speak of regrets, and Kitty kisses Gittes, who rejects her advances. She leaves, telling him to occasionally think of her. Gittes responds that it never goes away.

Cast[]

- Jack Nicholson as Jake Gittes

- Harvey Keitel as Julius "Jake" Berman

- Meg Tilly as Katherine "Kitty" Berman

- Madeleine Stowe as Lillian Bodine

- Eli Wallach as Cotton Weinberger

- Rubén Blades as Michael "Mickey Nice" Weisskopf

- Frederic Forrest as Chuck Newty

- David Keith as Det. Lt. Loach

- Richard Farnsworth as Earl Rawley

- Tracey Walter as Tyrone Otley

- Joe Mantell as Lawrence Walsh

- James Hong as Kahn

- Perry Lopez as Capt. Lou Escobar

- Jeff Morris as Ralph Tilton

- Rebecca Broussard as Gladys

- Van Dyke Parks as Hannah

- Pia Gronning as Elsa

- Luana Anders as Florist

- Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Mulwray (voice)

- Tom Waits as Plainclothes policeman (uncredited)

Production[]

Made 16 years after its famous predecessor, The Two Jakes had a very troubled production, and went through several iterations. Producer Robert Evans had the rights to a Chinatown sequel, and in 1976 had negotiated for Jack Nicholson to reprise his role and Dustin Hoffman to act alongside him; that version eventually fell through.[5] Screenwriter Robert Towne finished the script for The Two Jakes in 1984 and was set to direct (original director Roman Polanski had fled the States due to his guilty plea of unlawful sex with a minor and thus would be unable to return), but he objected to Evans's wish to act in the film in the Jake Berman role. Nicholson, Evans, and Towne had formed their own production company to make the film independently, and entered into a distribution deal with Paramount Pictures. The trio agreed to not take up-front salaries, and instead share in the film's profits. Paramount greenlit a $12–13 million budget, and capped its distribution fee at $6 million.

In April 1985, Kelly McGillis, Cathy Moriarty, Dennis Hopper, Joe Pesci, and Harvey Keitel had all been cast, ready to shoot the film that month.[6] The following month, the sets had been built and filming was ready to begin, but Towne's lack of confidence in Evans's acting ability exploded into a final argument when Evans objected to having to get a 1940s-style haircut (mostly due to recent plastic surgery scars that would be visible). Filming was scheduled to begin four days after the confrontation, with a witness telling Vanity Fair: "In the morning, nothing happened. They said the weather was wrong. But you could tell the plug had been pulled."[6] On top of existing problems between Nicholson, Towne, and Evans, grievances were filed by 120 crew members who had not been paid (over $500,000 from Screen Actors Guild and Directors Guild of America members, and $1.5 million from suppliers of sets, props, costumes, and sound stages), and the project was officially postponed indefinitely.[5]

Because the film hadn't been budgeted normally due to the initial Evans–Towne–Nicholson plan, Towne approached producer Dino De Laurentiis to help finance. McGillis remained in the cast, with Harrison Ford set to take over as Jake Gittes and Roy Scheider attached to play the other Jake, with a tentative start date of mid-1986. At one point the original film's star John Huston was rumored to be brought in as director, although Towne denied the claim. However, the constant shuffling worried Paramount, who withdrew from the distribution deal out of nervousness, eventually taking a $4 million loss on the film.[7] The project was discontinued until the late 1980s when Nicholson took on the responsibility of directing and also rewrote parts of Towne's script (which "was really only about 80% ready").[8] Filming began in Los Angeles on April 18, 1989, lasting through July 26.[5] Numerous scenes had to be reshot after initial filming had wrapped, causing the release date to get pushed from Christmas 1989 to its August 1990 date. However, Nicholson insisted that it came in "perfectly on schedule and perfectly on budget" (the final cost was about $25 million).[2] The film ended up in a personal fallout between Nicholson, Towne, and Evans, with Towne saying in 1998 that he hadn't spoken to Nicholson in over ten years, and Evans checking into a hospital for mental health and substance abuse issues.[6]

Reception[]

Box office[]

Unlike its predecessor, the film was not a box-office success.[9][10] It made $3.7 million from 1,206 theaters in its first weekend, finishing in seventh, then $1.8 million and $1.9 million in its second and third weekends, finishing 16th both times; it ended its theatrical run with $10 million at the box office, nearly a third less than the original.[3]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 64% based on 25 reviews, with an average rating of 5.9/10.[11] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 56 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[12] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "C+" on an A+ to F scale.[13]

Roger Ebert gave the film 3.5 out of 4 stars, writing that "every scene falls into place like clockwork [...] exquisite".[14] Vincent Canby, writing for The New York Times, called it "an enjoyable if clunky movie".[15] Variety called the film "a jumbled, obtuse yet not entirely unsatisfying follow-up to Chinatown".[16] Desson Howe, for The Washington Post, wrote that "at best, the movie comes across as a competently assembled job, a wistful tribute to its former self. At worst, it's wordy, confusing and – here's an ugly word – boring".[17]

Cancelled sequel[]

Screenwriter Robert Towne originally planned a trilogy involving private investigator J. J. Gittes. According to Nicholson, the third film, titled Gittes vs. Gittes, was "meant to be set in 1968 when no-fault divorce went into effect in California."[6] However, after The Two Jakes was a commercial failure, plans for a third film were scrapped.[18]

References[]

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ a b Jack Mathews (August 5, 1990). "Jake Laid-Back". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Two Jakes (1990)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth, eds. (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd., rev. and expanded. ed.). Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5.

- ^ a b c "Catalog - The Two Jakes". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Falk, Ben (November 5, 2007). "The crazy story behind the making of 'Chinatown' sequel 'The Two Jakes'". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Warren, James (October 30, 1985). "In Vanity Fair: The Saga of Why a 'Chinatown' Sequel Never Got Made". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ Lim, =Dennis (November 5, 2007). "Some respect for 'The Two Jakes'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ Broeske, Pat H. (August 13, 1990). "The Two Jakes Fails to Do Land-Office Business". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ^ Hunt, Dennis (March 14, 1991). "VIDEO RENTALS : Roberts Shows Her Box-Office Clout". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ "The Two Jakes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "The Two Jakes (1990)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Find CinemaScore" (Type "Two Jakes" in the search box). CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 10, 1990). "The Two Jakes". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (August 10, 1990). "A Jake Gittes Who's Older (And Wider)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ "The Two Jakes". Variety. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Howe, Desson (August 10, 1990). "The Two Jakes". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Horowitz, Josh (November 5, 2007). "Jack Nicholson Talks! In Rare Interview, Actor Reveals Details of Never-Shot 'Chinatown' Sequel". MTV News. Archived from the original on December 27, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Two Jakes |

- The Two Jakes at IMDb

- The Two Jakes at Box Office Mojo

- Feature story by Aljean Harmetz, The New York Times (September 10, 1989)

- 1990 films

- English-language films

- 1990 drama films

- 1990s crime drama films

- 1990s mystery films

- American crime drama films

- American detective films

- American films

- American mystery films

- American neo-noir films

- American sequel films

- Fictional duos

- Fictional portrayals of the Los Angeles Police Department

- Films directed by Jack Nicholson

- Films produced by Robert Evans

- Films scored by Van Dyke Parks

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in 1948

- Films with screenplays by Robert Towne

- Paramount Pictures films