The Witches (novel)

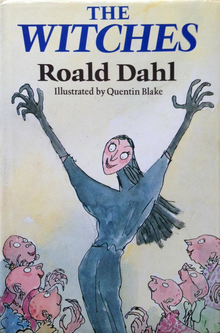

First edition cover | |

| Author | Roald Dahl |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Quentin Blake |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Genre | Children's fantasy Dark fantasy |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 1983 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 208 |

| Awards | Whitbread Book Award (1983) |

The Witches is a British children's dark fantasy novel by the British writer Roald Dahl. The story is set partly in Norway and partly in England, and features the experiences of a young English boy and his Norwegian grandmother in a world where child-hating societies of witches secretly exist in every country. The witches are ruled by the extremely vicious and powerful Grand High Witch, who arrives in England to organize her plan to turn all of the children in England into mice.

The Witches was originally published in 1983 by Jonathan Cape in London, with illustrations by Quentin Blake who had previously collaborated with Dahl. It is one of the top all-time children's novels, but received originally mixed reviews. The most common critique against the novel was based on perceived misogyny. The book was adapted into an unabridged audio reading by Lynn Redgrave, a stage play and a two-part radio dramatization for the BBC, a 1990 film directed by Nicolas Roeg which starred Anjelica Huston and Rowan Atkinson, an 2008 opera by Marcus Paus and Ole Paus, and a 2020 film directed by Robert Zemeckis.

Plot[]

The story is narrated from the perspective of an unnamed seven-year-old English boy, who goes to live with his Norwegian grandmother after his parents are killed in a tragic car accident. The boy loves all his grandmother's stories, but he is especially enthralled by the stories about real-life witches who she says are horrific female demons who seek to kill human children. She tells him how to recognise them, and that she is a retired witch hunter (she, herself, had an encounter with a witch when she was a child, which left her with a missing thumb). According to the boy's grandmother, a real witch looks exactly like an ordinary woman, but there are ways of telling whether she is a witch: real witches have claws instead of fingernails, which they hide by wearing gloves; are bald, which they hide by wearing wigs that often make them break out in rashes; have square feet with no toes, which they hide by wearing uncomfortable pointy shoes; have eyes with pupils that change colours; have blue spit which they use for ink, and have large nostrils which they use to sniff out children; to a witch, a child smells of fresh dogs droppings; the dirtier the child, the less likely she is to smell them.

As specified in the parents' will, the narrator and his grandmother return to England, where he was born and had attended school, and where the house he is inheriting is located. However, the grandmother warns the boy to be on his guard, since English witches are known to be among the most vicious in the world, notorious for turning children into loathsome creatures so that unsuspecting adults will kill them. She also assures him that there are fewer witches in England than there are in Norway.

The grandmother reveals that witches in different countries have different customs and that, while the witches in each country have close affiliations with one another, they are not allowed to communicate with witches from other countries. She also tells him about the mysterious Grand High Witch of All the World, the feared and diabolical leader of all of the world's witches, who visits their councils in every country, each year.

Shortly after arriving back in England, while the boy is working on the roof of his tree-house, he sees a strange woman in black staring up at him with an eerie smile, and he quickly registers that she is a witch. When the witch offers him a snake to tempt him to come down to her, he climbs further up the tree and stays there, not daring to come down until his grandmother comes looking for him. This persuades the boy and his grandmother to be especially wary, and he carefully scrutinizes all women to determine whether they might be witches.

When the grandmother becomes ill with pneumonia, the doctor orders her to cancel a planned holiday in Norway (she and her grandson had planned to go there). The doctor explains that pneumonia can be very dangerous when a person is 80 or older (she later reveals in the book that she is 86), and therefore, he cannot even move her to the hospital in her condition. Instead, about two weeks later when she has recovered, they go to a luxury hotel in Bournemouth on England's south coast. The boy is training his pet mice, William and Mary, given to him as a consolation present by his grandmother after the loss of his parents, in the hotel ballroom when the "Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children" show up for their annual meeting. When one of them reaches underneath her hair to scratch at her scalp with a gloved hand, the boy realizes that this is the yearly gathering of England's witches (all of the other women are wearing gloves as well), but he is trapped in the room.

A young woman goes on stage and removes her entire face, which is a mask. The narrator realizes that this is no other than the Grand High Witch herself. She expresses her displeasure at the English witches' failure to eliminate enough children, and thus demanding that they exterminate the lot of them before the next meeting. She exterminates a witch who questions whether it will be possible to wipe out all of the children of Britain. The Grand High Witch unveils her master plan: all of England's witches are to purchase sweet shops (with counterfeited money, printed by her from a magical money-making machine) and give away free sweets and chocolates laced with a drop of her latest creation: "Formula 86 Delayed-Action Mouse-Maker", a magic potion which turns the consumer into a mouse at a specified time set by the potion-maker. The intent is for the children's teachers and parents to unwittingly kill the transformed children, thus doing the witches' dirty work for them so that nobody will ever find the witches because they are unaware that it was their doing.

To demonstrate the formula's effectiveness, the Grand High Witch brings in a child named Bruno Jenkins, a rich and often greedy boy lured to the convention hall with the promise of free chocolate. She reveals that she had tricked Bruno into eating a chocolate bar laced with the formula the day before, and had set the "alarm" to go off during the meeting. The potion takes effect, transforming Bruno into a mouse before the assembled witches. Shortly after, the witches detect the narrator's presence and corner him. The Grand High Witch then pours an entire bottle of Formula 86 down his throat, and the overdose instantly turns him into a mouse. However, the transformed child retains his mentality, personality and even his voice - refusing to be lured into a mouse-trap. After tracking down Bruno, the transformed boy returns to his grandmother's hotel room and tells her what he has learned. He suggests turning the tables on the witches by slipping the potion into their evening meal. With some difficulty, he manages to get his hands on a bottle of the potion from the Grand High Witch's room.

After an attempt to return Bruno to his parents fails spectacularly, mainly due to his mother's fear of mice, the grandmother takes Bruno and the narrator to the dining hall. The narrator enters the kitchen, where he pours the potion into the green pea soup intended for the witches' dinner. On the way back from the kitchen, a cook spots the narrator and chops off part of his tail with a carving knife, before he manages to escape back to his grandmother. The witches all turn into mice within a few minutes, having had massive overdoses, just like the narrator. The hotel staff and the guests all panic and unknowingly end up killing the Grand High Witch and all of England's witches.

Having returned home, the boy and his grandmother then devise a plan to rid the world of witches. His grandmother has contacted the chief of police in Norway and discovered that the Grand High Witch was living in a castle in that country. They will travel to the Grand High Witch's Norwegian castle, and use the potion to change her successor and the successor's assistants into mice, then release cats to destroy them. Using the Grand High Witch's money-making machine and information on witches in various countries, they will try to eradicate them everywhere. The grandmother also reveals that, as a mouse, the boy will probably only live for about another nine years, but the boy does not mind, as he does not want to outlive his grandmother (she reveals that she is also likely to live for only nine more years), as he would hate to have anyone else look after him.

Background[]

Dahl based the novel on his own childhood experiences, with the character of the grandmother modeled after Sofie Dahl, the author’s mother.[1] The author was “well satisfied”[1] by his work on The Witches, a sentiment which literary biographer Robert Carrick believes may have come from the fact that the novel was a departure from Dahl’s usual “all-problem-solving finish.”[1] Dahl did not work on the novel alone; he was aided by editor Stephen Roxburgh, who helped rework The Witches.[2] Roxburgh’s advice was very extensive and covered areas such as improving plots, tightening up Dahl’s writing, and reinventing characters.[2] Soon after its publication, the novel received compliments for its illustrations done by Quentin Blake.[3]

Analysis[]

Due to the complexity of The Witches and its departure from a typical Dahl novel,[4] several academics have analyzed the work. One perspective offered by Castleton University professor James Curtis suggests that the rejection of the novel by parents is caused by its focus on “child-hate” and Dahl’s reluctance to shield children from such a reality.[5] The scholar argues that the book showcases a treatment of children that is not actually worse than historical and modern examples; however, Dahl’s determination to expose to his young readers the truth can be controversial.[6] Despite society occasionally making progress in its treatment of children, Curtis argues that different aspects of child-hate displayed in Dahl’s work are based on real world examples.[5] As the boy’s grandmother informs him, the witches usually strike children when they are alone; Curtis uses this information from the novel to connect to the historical problem of child abandonment.[7] As children have been maimed or killed due to abandonment, children are harmed by witches in the novel when they have been left alone.[5] Another analysis done by Union College professor Jennifer Mitchell suggests that through one of the opening lines Dahl is portraying the narrator, and therefore himself, as someone reliable and trustworthy as a teller of the truth that most adults are trying to shield children from.[6] According to Mitchell, the novel is a powerful tool for children to learn about gender identity. Mitchell makes the argument that the transition of the boy and Bruno Jenkins into mice, and their caretaker’s different reactions to such a transition, offers to readers the possible outcomes of queer children.[6] While the boy’s grandmother is supportive of his new mouse state, Bruno Jenkins’s parents react aggressively against their son's own transition.[6]

Reception[]

In 2012, The Witches was ranked number 81 among all-time children's novels in a survey published by School Library Journal, a monthly with primarily US audience. It was the third of four books by Dahl among the Top 100, more than any other writer.[citation needed] In November 2019, the BBC listed The Witches on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[8]

The novel received mainly positive reviews in the United States, but with a few warnings due to the more fear inducing parts of it.[9] Ann Waldron of the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote in her 1983 review that she would suggest not gifting the book to a child that is more emotional to particularly frightening scenarios.[9] Other mixed receptions were the results of Dahl’s depiction of the witches being monstrous in characterization.[10] Soon after its publication, the novel received compliments for its illustrations done by Quentin Blake.[9]

The Witches was banned by some libraries, due to perceived misogyny.[11] Despite The Witches original success, it began to be challenged not long after its publication due to the perceived viewpoint that witches are a “sexist concept.”[12] It appears on the American Library Association list of the 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990 to 1999, at number 22.[13] The possibility of misogynistic interpretations of the novel was discussed before it was released. Dahl’s editor Roxburgh offered concern with the negative gender associations depicted in the book during the editing process prior to the novel’s publication in 1983; Dahl brushed off these concerns by explaining he was not afraid of offending women.[14] Alex Carnevale of This Recording stated that the book is how boys learn to become men who hate women.[15]

Jemma Crew of the Newstatesman considers it an "unlikely source of inspiration for feminists".[16] The Times article "Not in Front of the Censors" suggests that the least interesting thing to a child about a witch is that they appear to look like a woman, and even offers the perspective that a witch might be a very feminist role model to a young school girl.[17]

Questions have also been raised about the ending of the book, with some critics suggesting it might encourage suicide in children by telling them they can avoid growing up by dying.[18]

Adaptations[]

1990 film[]

In 1990, The Witches was adapted into a film starring Anjelica Huston and Rowan Atkinson, directed by Nicolas Roeg, co-produced by Jim Henson, and distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures. In the film, the boy is American and named Luke Eveshim, his grandmother is named Helga Eveshim, and The Grand High Witch is named Evangeline Ernst.

The most notable difference from the book is that the boy is restored to human form at the end of the story by the Grand High Witch's assistant (a character who does not appear in the book), who had renounced her former evil. Dahl regarded the film as "utterly appalling".[19]

Radio drama[]

In 2008, the BBC broadcast a two-part dramatisation of the novel by Lucy Catherine and directed by Claire Grove. The cast included Margaret Tyzack as the Grandmother, Toby Jones as the Narrator, Ryan Watson as the Boy, Jordan Clarke as Bruno and Amanda Laurence as the Grand High Witch.[citation needed]

Opera[]

The book was adapted into an opera by Norwegian composer Marcus Paus and his father, Ole Paus, who wrote the libretto. It premiered in 2008.[20]

2020 film[]

Another film adaptation co-written and directed by Robert Zemeckis was released October 22, 2020 on HBO Max, after it was removed from its original release date due to COVID-19 pandemic. The most notable difference from the book is that this adaptation takes place in 1968 Alabama, and the protagonist is an African-American boy who is called "Hero Boy".[21] The adaptation also stays true to the book's ending rather than the 1990 film, having the protagonist stay a mouse at the end.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Carrick, Robert (2002). "Roald Dahl". Gale Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hulbert, Ann (1 May 1994). "'Roald the Rotten'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Waldron, Ann (30 October 1983). "THE WITCHES". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Carrick, Robert (2002). "Roald Dahl". Gale Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Curtis, James M. (June 2014). ""We Have a Great Task Ahead of Us!": Child-Hate in Roald Dahl's The Witches". Children's Literature in Education. 45 (2): 166–177. doi:10.1007/s10583-013-9207-6. ISSN 0045-6713. S2CID 161524696.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mitchell, Jennifer (2012). ""A Sort of Mouse-Person": Radicalizing Gender in The Witches". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 23: 25–39 – via Proquest.

- ^ author., Dahl, Roald. The witches. ISBN 978-0-241-43881-7. OCLC 1225155527.

- ^

"100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Waldron, Ann (30 October 1983). "THE WITCHES". Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Curtis, James M. (June 2014). ""We Have a Great Task Ahead of Us!": Child-Hate in Roald Dahl's The Witches". Children's Literature in Education. 45 (2): 166–177. doi:10.1007/s10583-013-9207-6. ISSN 0045-6713. S2CID 161524696.

- ^ Molly Driscoll (28 September 2011). "20 banned books that may surprise you - "The Witches," by Roald Dahl". CSMonitor.com. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Not in front of the Censors". Times. 24 November 1986.

- ^ "100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999 | ala.org/bbooks". Ala.org. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Mitchell, Jennifer (2012). ""A Sort of Mouse-Person": Radicalizing Gender in The Witches". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 23: 25–39 – via Proquest.

- ^ Carnevale, Alex. "The Angry Man".

- ^ Crew, Jemma (18 April 2013). "What can we learn from Roald Dahl's The Witches?". NewStatesman. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "Not in front of the Censors". Times. 24 November 1986.

- ^ Anderson, Hephzibah. "The dark side of Roald Dahl".

- ^ Bishop, Tom (11 July 2005). "Entertainment | Willy Wonka's everlasting film plot". BBC News.

- ^ "Hekseopera for barn - Programguide for alle kanaler - TV 2, NRK, TV3, TVN". Tv2.no. 18 December 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: Robert Zemeckis' 'The Witches' Remake Is Set In Alabama and Casting African-American Male Lead". 7 November 2018.

External links[]

- 1983 British novels

- 1983 children's books

- BILBY Award-winning works

- British children's novels

- British fantasy novels

- British novels adapted into films

- Demons in written fiction

- Children's books by Roald Dahl

- Children's fantasy novels

- Costa Book Award-winning works

- Dark fantasy novels

- Jonathan Cape books

- Novels by Roald Dahl

- Novels adapted into operas

- Witchcraft in written fiction

- Fiction about curses

- Fiction about shapeshifting

- First-person narrative novels