Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

| Chitty Chitty Bang Bang | |

|---|---|

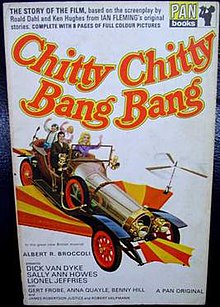

Original movie poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Hughes |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang by Ian Fleming |

| Produced by | Albert R. Broccoli |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Christopher Challis |

| Edited by | John Shirley |

| Music by |

|

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 145 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[3] or $12 million[4] |

| Box office | $7.5 million (rentals)[5] |

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang is a 1968 musical-fantasy film directed by Ken Hughes with a screenplay co-written by Roald Dahl and Hughes, loosely based on Ian Fleming's novel Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car (1964). The film stars Dick Van Dyke, Sally Ann Howes, Adrian Hall, Heather Ripley, Lionel Jeffries, Benny Hill, James Robertson Justice, Robert Helpmann, Barbara Windsor and Gert Fröbe.

The film was produced by Albert R. Broccoli. John Stears supervised the special effects. Irwin Kostal supervised and conducted the music, while the musical numbers, written by Richard M. and Robert B. Sherman, were staged by Marc Breaux and Dee Dee Wood. The song "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang" was nominated for an Academy Award.[6]

Plot[]

At a rural England garage, two children, Jeremy and Jemima Potts, find a car formerly used for racing in the European Grand Prix until it crashed and burned in 1909. They beg their father, inventor Caractacus, to get it for them; he makes multiple unsuccessful attempts to sell his inventions in order to raise money to buy it, until he earns tips from a song-and-dance act at a carnival. He purchases the car and rebuilds it with a new name, "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang" for the unusual noise of its engine. In the first trip in the car, Caractacus, the children, and a wealthy woman they've had unflattering encounters with before, Truly Scrumptious, picnic on the beach. Caractacus tells them a tale about nasty Baron Bomburst, the tyrant of fictional Vulgaria, who wants to steal Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

The story starts with the quartet escaping Bomburst's pirates. The Baron then sends two spies to capture the car, but they capture Lord Scrumptious, then Grandpa Potts by accident, mistaking each for the car's creator. Caractacus, Truly, and the children see their Grandpa, Bungie Potts, being taken away by airship, following it to Vulgaria, which involves the car sprouting wings and propellers to fly. Grandpa is taken to the castle, and has been ordered by the Baron to make another floating car just for him. He bluffs his abilities to the Baron to avoid being executed. The Potts' party is helped and hidden by the local Toymaker, who now works only for the childish Baron. Chitty is discovered and then taken to the castle. While Caractacus and the toymaker search for Grandpa and Truly searches for food, the children are kidnapped by the Baroness's Child Catcher, as children are not permitted in Vulgaria under Bomburst's rule.

The Toymaker takes Truly and Caractacus to a grotto beneath the castle where the townspeople have been hiding their children. They concoct a scheme to free the children and the village from the Baron. The Toymaker sneaks them into the castle disguised as life-size dolls for the Baron's birthday. Caractacus snares the Baron, and the children swarm into the banquet hall, overcoming the Baron's palace guards and guests. In the ensuing chaos, the Baron, Baroness, and the evil Child Catcher are captured. Chitty comes to their rescue and, at the same time, they are reunited with Grandpa. The Potts family and Truly bid farewell to the Toymaker and the rest of the village, then fly back home to England.

When Caractacus finishes the story, they set off for home, stopping to drop Truly off at Scrumptious Manor, where Caractacus dismisses any possibility of them having a future together, with what she regards as inverted snobbery. The Potts family arrive back at their cottage where Lord Scrumptious surprises Caractacus with an offer to buy one of his inventions, the Toot Sweets, as a canine confection, re-naming them Woof Sweets. Caractacus, realising that he will be rich, rushes to tell Truly the news. They kiss, and Truly agrees to marry him. As they drive home, he acknowledges the importance of pragmatism as the car takes off into the air again, this time without wings.

Cast[]

The cast includes:[7]

- Dick Van Dyke as Caractacus Potts

- Sally Ann Howes as Truly Scrumptious

- Adrian Hall as Jeremy Potts

- Heather Ripley as Jemima Potts

- Lionel Jeffries as Grandpa Bungie Potts

- Gert Fröbe as Baron Bomburst

- Anna Quayle as Baroness Bomburst

- Benny Hill as the Toymaker

- James Robertson Justice as Lord Scrumptious

- Robert Helpmann as the Child Catcher

- Barbara Windsor as Blonde

- Davy Kaye as Admiral

- Stanley Unwin as the Chancellor

- Peter Arne as the Captain of the Guard

- Desmond Llewelyn as Mr. Coggins

- Victor Maddern as Junkman

- Arthur Mullard as Cyril

- Max Wall as Inventor

- Gerald Campion as Minister

- Max Bacon as Orchestra Leader

- Alexander Doré as First Spy

- Bernard Spear as Second Spy

- Richard Wattis as Secretary at Sweet Factory (uncredited)

- Phil Collins as Vulgarian Child (scene cut)

The part of Truly Scrumptious had originally been offered to Julie Andrews, to reunite her with Van Dyke after their success in Mary Poppins. Andrews rejected the role specifically because she considered that the part was too close to Poppins.[8] Sally Ann Howes was given the role. Van Dyke was cast after he turned down the role of Fagin from the 1968 musical Oliver!.

Production[]

Fleming used to tell stories about the flying car to his infant son. After the author had a heart attack in 1961, he decided to write up the stories as a novel.[9] He wrote the book in longhand as his wife had confiscated his typewriter to force him to rest.

The novel was published in 1964 after Ian Fleming's death.[10] The book became one of the best selling children's books of the year.[11] Albert Broccoli, who produced the James Bond films, based on novels by Ian Fleming, read the novel and was not enthusiastic about turning it into a film. He changed his mind after the success of Mary Poppins.[9]

In December 1965, it was reported Earl Hamner had completed a script from the novel.[12] In July 1966, it was announced the film would be produced by Albert Broccoli. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman produced the James Bond films but would do separate projects as well; Chitty Chitty was done by Broccoli alone.[13]

In December 1966. Broccoli announced that Dick Van Dyke would play the lead.[14] It was the first in a multi-picture deal Van Dyke signed with United Artists.[15] By April 1967, Sally Ann Howes was set to play the female lead, and Ken Hughes would direct from a Roald Dahl script.[16] Howes was signed to a five-picture contract with Broccoli.[17] It was the first film for the child stars, and they were cast after an extensive talent search.[18] Robert Helpmann joined the cast in May.[19]

The film's songs were written by the Sherman Brothers, who had previously composed the music for Mary Poppins.[20] Director Ken Hughes claimed he had to rewrite the script.[9]

The Caractacus Potts inventions in the film were created by Rowland Emett. In 1976, Time magazine, describing Emett's work, wrote that no term other than "Fantasticator...could remotely convey the diverse genius of the perky, pink-cheeked Englishman whose pixilations, in cartoon, watercolor and clanking 3-D reality, range from the celebrated Far Tottering and Oyster Creek Railway to the demented thingamabobs that made the 1968 movie Chitty Chitty Bang Bang a minuscule classic."[21]

Ken Adam designed the titular car,[22] and six Chitty-Chitty Bang-Bang cars were created for the film, only one of which was fully functional. At a 1973 auction in Florida, one sold for $37,000, equal to $215,704 today.[23] The original "hero" car, in a condition described as fully functional and road-going, was offered at auction on 15 May 2011 by a California-based auction house.[24] The car sold for $805,000, less than the $1 million to $2 million it was expected to reach.[25] It was purchased by New Zealand film director Sir Peter Jackson.[26]

Filming started June 1967 at Pinewood Studios.[9]

Locations[]

| Feature in film | Location of filming |

|---|---|

| Scrumptious Sweet Co. factory (exterior) | Kempton Waterworks, Snakey Lane, Hanworth, Greater London, England.[27] This location now includes a steam museum open to the public. |

| Scrumptious Mansion | Heatherden Hall at Pinewood Studios in Iver Heath, Buckinghamshire, England[27] |

| Windmill/Cottage | Cobstone Windmill in Ibstone, near Turville, Buckinghamshire, England.[27] Also known as Turville Windmill. |

| Duck Pond | Russell's Water, Oxfordshire, England[27] |

| Train scene | The Longmoor Military Railway, Hampshire, England. This line closed in 1968, the same year the film was released. |

| Beach | Cap Taillat, Saint-Tropez, France |

| River bridge where spies attempt to blow up Chitty | Iver Bridge, Iver, Buckinghamshire, England. This bridge is Grade II listed. |

| Railway bridge where spies kidnap Lord Scrumptious | Ilmer Bridge, Ilmer, Buckinghamshire, England. This bridge carries the Chiltern Main line between Birmingham and Marylebone. |

| White rock spires in the ocean and lighthouse | The Needles stacks, Isle of Wight, England |

| White cliffs | Beachy Head, East Sussex, England |

| Baron Bomburst's castle (exterior) | Neuschwanstein Castle, Bavaria, Germany |

| Vulgarian village | Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Bavaria, Germany |

Release[]

United Artists promoted the film with an expensive, extensive advertising campaign, hoping for another Sound of Music. The movie was released on a roadshow basis.[4]

Reception[]

Original release[]

Time began its review by stating the film is a "picture for the ages—the ages between five and twelve" and ended noting that "At a time when violence and sex are the dual sellers at the box office, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang looks better than it is simply because it's not not all all bad bad"; the film's "eleven songs have all the rich melodic variety of an automobile horn. Persistent syncopation and some breathless choreography partly redeem it, but most of the film's sporadic success is due to director Ken Hughes's fantasy scenes, which make up in imagination what they lack in technical facility."[28]

The New York Times critic Renata Adler wrote "in spite of the dreadful title, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang...is a fast, dense, friendly children's musical, with something of the joys of singing together on a team bus on the way to a game"; Adler called the screenplay "remarkably good" and the film's "preoccupation with sweets and machinery seems ideal for children"; she ends her review on the same note as Time: "There is nothing coy, or stodgy or too frightening about the film; and this year, when it has seemed highly doubtful that children ought to go to the movies at all, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang sees to it that none of the audience's terrific eagerness to have a good time is betrayed or lost."[29]

Box-office[]

The film was the tenth most popular at the U.S. box-office in 1969.[30] However, because of its high budget, it lost United Artists an estimated $8 million during its theatrical run. Five films produced by Harry Saltzman, including The Battle of Britain, lost UA $19 million. This contributed to United Artists scaling back its operations in the UK.[31]

Later responses[]

Film critic Roger Ebert wrote: "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang contains about the best two-hour children's movie you could hope for, with a marvelous magical auto and lots of adventure and a nutty old grandpa and a mean Baron and some funny dances and a couple of [scary] moments."[32]

Filmink stated " It's a gorgeous looking movie with divine sets, a fabulous cast and cheerful songs; it's also, like so many late ‘60s musicals, far too long and would have been better at a tight 90 minutes."[33]

As of 22 July 2019, the film has a 67% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 27 reviews with an average rating of 5.63/10.[34]

Soundtrack[]

The original soundtrack album, as was typical of soundtrack albums of the period, is actually an original CAST soundtrack featuring studio re-recordings of all the songs by the original cast and orchestra. None of the soundtrack songs lock to picture, and the album presented mostly songs with very few instrumental tracks or underscoring.

The soundtrack has been released on CD four times, the first two releases using the original LP masters rather than going back to the original music masters to compile a more complete soundtrack album with underscoring and complete versions of songs. The 1997 Rykodisc release included several quick bits of dialogue from the film between some of the tracks, but otherwise used the same LP master and has gone out of circulation. On 24 February 2004, a few short months after MGM released the movie on a 2-Disc Special Edition DVD, Varèse Sarabande reissued a newly remastered soundtrack album without the dialogue tracks, restoring it to its original 1968 LP format.

In 2011, Kritzerland released the definitive soundtrack album, a two-CD set featuring the original soundtrack album plus bonus tracks, music from the song and picture book album on disc 1, and the Richard Sherman demos, as well as six playback tracks (including a long version of international covers of the theme song). Inexplicably, this release was limited to only 1,000 units.[35]

In April 2013, Perseverance Records re-released the Kritzerland double CD set with expansive new liner notes by John Trujillo and a completely new designed booklet by Perseverance regular James Wingrove.

No definitive release of the original film soundtrack featuring the performances that lock to picture without the dialogue and effects, especially featuring the underscoring tracks can be made due to the fact that the original isolated scoring session recordings were lost or discarded once United Artists merged its archives. All that is left is the 6-track 70MM sound mix with the other elements already added in.

Musical Numbers

- "You Two" – Caractacus, Jeremy and Jemima

- "Toot Sweets" – Caractacus, Truly, Jeremy, Jemima and factory workers

- "Hushabye Mountain" – Caractacus

- "Me Ol' Bamboo" – Caractacus and carnival dancers

- "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang" – Caractacus, Truly, Jeremy and Jemima

- "Truly Scrumptious" – Jemima, Jeremy and Truly

- "Lovely Lonely Man" – Truly

- "Posh!" – Grandpa

- "The Roses of Success" – Grandpa and inventors

- "Hushaby Mountain (Reprise)" – Caractacus and Truly

- "Chu-Chi Face" – Baron and Baroness

- "Doll on a Music Box/Truly Scrumptious (Reprise)" – Truly and Caractacus

- "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (Finale)" – Caractacus, Truly along with the rest of the cast during the last verse

Home media[]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2010) |

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was released numerous times in the VHS format as well as Betamax, CED, and LaserDisc. In 1998, the film saw its first DVD release. The year 2003 brought a two-disc "Special Edition" release. On 2 November 2010, MGM Home Entertainment through 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment released a two-disc Blu-ray and DVD combination featuring the extras from the 2003 release as well as new features. The 1993 LaserDisc release by MGM/UA Home Video was the first home video release with the proper 2.20:1 Super Panavision 70 aspect ratio.

Adaptations[]

Novelisation of film[]

The film did not follow Fleming's novel closely. A separate novelisation of the film was published at the time of the film's release. It basically followed the film's story but with some differences of tone and emphasis, e.g. it mentioned that Caractacus Potts had had difficulty coping after the death of his wife, and it made it clearer that the sequences including Baron Bomburst were extended fantasy sequences. It was written by John Burke.[36]

Scale models[]

Corgi Toys released a scale replica of the airship with working features such as pop out wings.[37] Mattel Toys also produced a replica with different features, while Aurora produced a detailed hobby kit of the car.[38]

Comic book adaption[]

- Gold Key: Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Gold Key Comics. February 1969.[39]

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang's Adventure in Tinkertown[]

An educational PC game was released in October 1996, featuring the titular car where players have to solve puzzles to complete the game.[40]

Musical Stage adaptation[]

A musical was adapted for the stage. The music and lyrics were written by Richard and Robert Sherman with book by Jeremy Sams. The musical premiered in the West End at the London Palladium on 16 April 2002 with six new songs by the Sherman Brothers. The Broadway production opened on 28 April 2005 at the Lyric Theatre (then the Hilton Theatre). After its closing in London, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang toured around the UK. The UK Tour visited Asia when it opened on 2 November 2007 in Singapore. The Australian national production opened on 17 November 2012. The German premiere took place on 30 April 2014.[citation needed]

References[]

- ^ "CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG (U)". British Board of Film Classification. 18 October 1968. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1969)". BFI. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968)". FlickFacts. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Advertising: First Bang of a Big Bang Bang By PHILIP H. DOUGHERTY. The New York Times 30 April 1968: 75.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1969". Variety. Penske Business Media. 7 January 1970. p. 15. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ "About Ian Fleming". Ian Fleming Centenary. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang". Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. Archived from the original on 19 June 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Stirling, Richard (2009). Julie Andrews: An Intimate Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312380250.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Burke, Tom (22 October 1967). "Kid Stuff From Ian Fleming?". The New York Times. p. 155.

- ^ "IN AND OUT OF BOOKS", by LEWIS NICHOLS. The New York Times, 30 Aug 1964: BR8.

- ^ "CHILDREN'S BEST SELLERS", The New York Times, 7 November 1965: BRA48.

- ^ "Meet Moviemaker Richard Rodgers", by A.H. WEILER. The New York Times, 12 Dec 1965: X11.

- ^ "Pint-Sized Bonded Stuff on Tap: More About Movies", by A.H. WEILER. The New York Times, 10 July 1966: 81.

- ^ "Fleming film", The Christian Science Monitor, 23 Dec 1966: 6.

- ^ MOVIE CALL SHEET: Van Dyke to StaIar in 'Chitty' Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times, 23 Dec 1966: C6.

- ^ "Miss Howes Joins 'Chitty'", Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times, 12 Apr 1967: e13.

- ^ "Milton Berle to Join 'Angels'", Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times, 2 Aug 1967: d12.

- ^ "2 Young Thespians Truly Scrumptious", Fuller, Stephanie. Chicago Tribune, 22 Dec 1968: f14.

- ^ "'Insurgents' for Crenna", Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times, 31 May 1967: d12.

- ^ "Song Writing Team Eschews Gimmicks", by MUSEL, ROBERT. Los Angeles Times, 24 May 1967: e9.

- ^ "Modern Living: The Gothic-Kinetic Merlin of Wild Goose Cottage". Time. 1 November 1976. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "FOCUS OF THE WEEK: IAN FLEMING & CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG". James Bond 007. 18 September 2018. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ "Modern Living: Crazy-Car Craze". Time. 30 April 1973. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Profiles (25 April 2011). "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang to be Sold at Auction" (Press release). Profiles in History. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Lewis, Andy (16 May 2011). "'Chitty Chitty Bang Bang'Car Undersells at Auction". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Cooke, Michelle (22 October 2011). "Jackson picks up Chitty Chitty Bang Bang". The Dominion Post. Stuff. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Where was 'Chitty Chitty Bang Bang' filmed?". British Film Locations. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ "New Movies: Chug-Chug, Mug-Mug". Time. 27 December 1968. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Adler, Renata (19 December 1968). "'Chitty Chitty Bang Bang': Fast, Friendly Musical for Children Bows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "The World's Top Twenty Films". The Sunday Times. 27 September 1970. p. 27 – via The Sunday Times Digital Archive.

- ^ Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists : the company that changed the film industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 133.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (24 December 1968). "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (14 November 2020). "Ken Hughes Forgotten Auteur". Filmink. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang". Kritzerland. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Burke, John Frederick; Fleming, Ian (1968). Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Story of the Film. Pan Books. ISBN 9780330022071. OCLC 1468311.

- ^ "Toy info". Toymart.com. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "Chitty". Mikemercury.net. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "Gold Key: Chitty Chitty Bang Bang". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Giovetti, Al. "Chitty Chitty Bang Bang's Adventure in Tinkertown". thecomputershow.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (film). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Chitty Chitty Bang Bang |

- Chitty Chitty Bang Bang at IMDb

- Chitty Chitty Bang Bang at the TCM Movie Database

- Chitty Chitty Bang Bang at AllMovie

- Chitty Chitty Bang Bang at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Chitty Chitty Bang Bang at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1968 films

- English-language films

- Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

- 1960s musical fantasy films

- 1960s fantasy adventure films

- American films

- American aviation films

- American children's adventure films

- American children's fantasy films

- American fantasy adventure films

- American musical fantasy films

- British films

- British aviation films

- British children's adventure films

- British children's fantasy films

- British fantasy adventure films

- British musical fantasy films

- 1960s fantasy-comedy films

- Films about kidnapping

- Films about automobiles

- Films adapted into comics

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on children's books

- Films directed by Ken Hughes

- Films produced by Albert R. Broccoli

- Films set in Europe

- Films set in the 1910s

- Films shot in Bavaria

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Germany

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Films shot in Saint-Tropez

- Flying cars in fiction

- Musicals by the Sherman Brothers

- Films with screenplays by Roald Dahl

- Varèse Sarabande albums

- 1960s children's adventure films

- 1960s children's fantasy films

- Films scored by Irwin Kostal

- Films with screenplays by Richard Maibaum

- American fantasy-comedy films

- British fantasy comedy films

- 1968 comedy films