Times Higher Education World University Rankings

| |

| Editor | Phil Baty |

|---|---|

| Categories | Higher education |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Publisher | Times Higher Education |

| First issue | 2010 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Website | www |

Times Higher Education World University Rankings is an annual publication of university rankings by Times Higher Education (THE) magazine. The publisher had collaborated with Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) to publish the joint THE-QS World University Rankings from 2004 to 2009 before it turned to Thomson Reuters for a new ranking system from 2010–2013. The magazine signed a new deal with Elsevier in 2014 who now provide them with the data used to compile the rankings.[1]

The publication now comprises the world's overall, subject, and reputation rankings, alongside three regional league tables, Asia, Latin America, and BRICS & Emerging Economies which are generated by different weightings.

THE Rankings is often considered one of the most widely observed university rankings together with Academic Ranking of World Universities and QS World University Rankings.[2][3][4][5][6] It is praised for having a new, improved ranking methodology since 2010; however, undermining of non-science and non-English instructing institutions and relying on subjective reputation survey are among the criticism and concerns.[3][7][8]

History[]

The creation of the original Times Higher Education–QS World University Rankings was credited in Ben Wildavsky's book, The Great Brain Race: How Global Universities are Reshaping the World,[9] to then-editor of Times Higher Education, John O'Leary. Times Higher Education chose to partner with educational and careers advice company QS to supply the data.

After the 2009 rankings, Times Higher Education took the decision to break from QS and signed an agreement with Thomson Reuters to provide the data for its annual World University Rankings from 2010 onwards. The publication developed a new rankings methodology in consultation with its readers, its editorial board and Thomson Reuters. Thomson Reuters will collect and analyse the data used to produce the rankings on behalf of Times Higher Education. The first ranking was published in September 2010.[10]

Commenting on Times Higher Education's decision to split from QS, former editor Ann Mroz said: "universities deserve a rigorous, robust and transparent set of rankings – a serious tool for the sector, not just an annual curiosity." She went on to explain the reason behind the decision to continue to produce rankings without QS' involvement, saying that: "The responsibility weighs heavy on our shoulders...we feel we have a duty to improve how we compile them."[11]

Phil Baty, editor of the new Times Higher Education World University Rankings, admitted in Inside Higher Ed: "The rankings of the world's top universities that my magazine has been publishing for the past six years, and which have attracted enormous global attention, are not good enough. In fact, the surveys of reputation, which made up 40 percent of scores and which Times Higher Education until recently defended, had serious weaknesses. And it's clear that our research measures favored the sciences over the humanities."[12]

He went on to describe previous attempts at peer review as "embarrassing" in The Australian: "The sample was simply too small, and the weighting too high, to be taken seriously."[13] THE published its first rankings using its new methodology on 16 September 2010, a month earlier than previous years.[14]

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings, along with the QS World University Rankings and the Academic Ranking of World Universities are described to be the three most influential international university rankings.[4][15] The Globe and Mail in 2010 described the Times Higher Education World University Rankings to be "arguably the most influential."[16]

In 2014 Times Higher Education announced a series of important changes to its flagship THE World University Rankings and its suite of global university performance analyses, following a strategic review by THE parent company TES Global.[17]

Methodology[]

Criteria and weighing[]

The inaugural 2010-2011 methodology contained 13 separate indicators grouped under five categories: Teaching (30 percent of final score), research (30 percent), citations (research impact) (worth 32.5 percent), international mix (5 percent), industry income (2.5 percent). The number of indicators is up from the Times-QS rankings published between 2004 and 2009, which used six indicators.[18]

A draft of the inaugural methodology was released on 3 June 2010. The draft stated that 13 indicators would first be used and that this could rise to 16 in future rankings, and laid out the categories of indicators as "research indicators" (55 percent), "institutional indicators" (25 percent), "economic activity/innovation" (10 percent), and "international diversity" (10 percent).[19] The names of the categories and the weighting of each was modified in the final methodology, released on 16 September 2010.[18] The final methodology also included the weighting signed to each of the 13 indicators, shown below:[18]

| Overall indicator | Individual indicator | Percentage weighting |

|---|---|---|

| Industry Income – innovation |

|

|

| International diversity |

|

|

| Teaching – the learning environment |

|

|

| Research – volume, income and reputation |

|

|

| Citations – research influence |

|

|

The Times Higher Education billed the methodology as "robust, transparent and sophisticated," stating that the final methodology was selected after considering 10 months of "detailed consultation with leading experts in global higher education," 250 pages of feedback from "50 senior figures across every continent" and 300 postings on its website.[18] The overall ranking score was calculated by making Z-scores all datasets to standardize different data types on a common scale to better make comparisons among data.[18]

The reputational component of the rankings (34.5 percent of the overall score – 15 percent for teaching and 19.5 percent for research) came from an Academic Reputation Survey conducted by Thomson Reuters in spring 2010. The survey gathered 13,388 responses among scholars "statistically representative of global higher education's geographical and subject mix."[18] The magazine's category for "industry income – innovation" came from a sole indicator, institution's research income from industry scaled against the number of academic staff." The magazine stated that it used this data as "proxy for high-quality knowledge transfer" and planned to add more indicators for the category in future years.[18]

Data for citation impact (measured as a normalized average citation per paper), comprising 32.5 percent of the overall score, came from 12,000 academic journals indexed by Thomson Reuters' large Web of Science database over the five years from 2004 to 2008. The Times stated that articles published in 2009–2010 have not yet completely accumulated in the database.[18] The normalization of the data differed from the previous rankings system and is intended to "reflect variations in citation volume between different subject areas," so that institutions with high levels of research activity in the life sciences and other areas with high citation counts will not have an unfair advantage over institutions with high levels of research activity in the social sciences, which tend to use fewer citations on average.[18]

The magazine announced on 5 September 2011 that its 2011–2012 World University Rankings would be published on 6 October 2011.[20] At the same time, the magazine revealed changes to the ranking formula that will be introduced with the new rankings. The methodology will continue to use 13 indicators across five broad categories and will keep its "fundamental foundations," but with some changes. Teaching and research will each remain 30 percent of the overall score, and industry income will remain at 2.5 percent. However, a new "international outlook – staff, students and research" will be introduced and will make up 7.5 percent of the final score. This category will include the proportion of international staff and students at each institution (included in the 2011–2012 ranking under the category of "international diversity"), but will also add the proportion of research papers published by each institution that are co-authored with at least one international partner. One 2011–2012 indicator, the institution's public research income, will be dropped.[20]

On 13 September 2011, the Times Higher Education announced that its 2011–2012 list will only rank the top 200 institutions. Phil Baty wrote that this was in the "interests of fairness," because "the lower down the tables you go, the more the data bunch up and the less meaningful the differentials between institutions become." However, Baty wrote that the rankings would include 200 institutions that fall immediately outside the official top 200 according to its data and methodology, but this "best of the rest" list from 201 to 400 would be unranked and listed alphabetically. Baty wrote that the magazine intentionally only ranks around 1 percent of the world's universities in a recognition that "not every university should aspire to be one of the global research elite."[21] However, the 2015/16 edition of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings ranks 800 universities, while Phil Baty announced that the 2016/17 edition, to be released on 21 September 2016, will rank "980 universities from 79 countries".[22][23]

The methodology of the rankings was changed during the 2011-12 rankings process, with details of the changed methodology here.[24] Phil Baty, the rankings editor, has said that the THE World University Rankings are the only global university rankings to examine a university's teaching environment, as others focus purely on research.[25] Baty has also written that the THE World University Rankings are the only rankings to put arts and humanities and social sciences research on an equal footing to the sciences.[26] However, this claim is no longer true. In 2015, QS introduced faculty area normalization to their QS World University Rankings, ensuring that citations data was weighted in a way that prevented universities specializing in the Life Sciences and Engineering from receiving undue advantage.[27]

In November 2014, the magazine announced further reforms to the methodology after a review by parent company TES Global. The major change being all institutional data collection would be bought in house severing the connection with Thomson Reuters. In addition, research publication data would now be sourced from Elsevier's Scopus database.[28]

Reception[]

The reception to the methodology was varied.

Ross Williams of the Melbourne Institute, commenting on the 2010–2011 draft, stated that the proposed methodology would favour more focused "science-based institutions with relatively few undergraduates" at the expense of institutions with more comprehensive programmes and undergraduates, but also stated that the indicators were "academically robust" overall and that the use of scaled measures would reward productivity rather than overall influence.[7] Steve Smith, president of Universities UK, praised the new methodology as being "less heavily weighted towards subjective assessments of reputation and uses more robust citation measures," which "bolsters confidence in the evaluation method."[29] David Willetts, British Minister of State for Universities and Science praised the rankings, noting that "reputation counts for less this time, and the weight accorded to quality in teaching and learning is greater."[30] In 2014, David Willetts became chair of the TES Global Advisory Board, responsible for providing strategic advice to Times Higher Education.[31]

Criticism[]

Times Higher Education places a high importance on citations to generate rankings. Citations as a metric for effective education is problematic in many ways, placing universities who do not use English as their primary language at a disadvantage.[32] Because English has been adopted as the international language for most academic societies and journals, citations and publications in a language different from English are harder to come across.[33] Thus, such a methodology is criticized for being inappropriate and not comprehensive enough.[34] A second important disadvantage for universities of non-English tradition is that within the disciplines of social sciences and humanities the main tool for publications are books which are not or only rarely covered by digital citations records.[35]

Times Higher Education has also been criticized for its strong bias towards institutions that taught 'hard science' and had high quality output of research in these fields, often to the disadvantage of institutions focused on other subjects like the social sciences and humanities. For instance in the former THE-QS World University Rankings, the London School of Economics (LSE) was ranked 11th in the world in 2004 and 2005, but dropped to 66th and 67th in the 2008 and 2009 edition.[36] In January 2010, THE concluded the method employed by Quacquarelli Symonds, who conducted the survey on their behalf, was flawed in such a way that bias was introduced against certain institutions, including LSE.[37]

A representative of Thomson Reuters, THE's new partner, commented on the controversy: "LSE stood at only 67th in the last Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings – some mistake surely? Yes, and quite a big one."[37] Nonetheless, after the change of data provider to Thomson Reuters the following year, LSE fell to 86th place, with the ranking described by a representative of Thomson Reuters as 'a fair reflection of their status as a world class university'.[38] LSE despite being ranked continuously near the top in its national rankings, has been placed below other British universities in the Times Higher Education World Rankings in recent years, other institutions such as Sciences Po have suffered due to the inherent methodology bias still used.[citation needed] Trinity College Dublin's ranking in 2015 and 2016 was lowered by a basic mistake in data it had submitted; education administrator Bahram Bekhradnia said the fact this went unnoticed evinced a "very limited checking of data" "on the part of those who carry out such rankings". Bekhradnia also opined "while Trinity College was a respected university which could be relied upon to provide honest data, unfortunately that was not the case with all universities worldwide."[39]

In general it is not clear who the rankings are made for. Many students, especially the undergraduate students, are not interested in the scientific work of a facility of higher education. Also the price of the education has no effects on the ranking. That means that private universities on the North American continent are compared to the European universities. Many European countries like France, Sweden or Germany for example have a long tradition on offering free education within facilities of higher education.[40][41]

In 2021, the University of Tsukuba in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, was alleged to have submitted falsified data on the number of international students enrolled at the university to the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[42] The discovery resulted in an investigation by THE and the provision of guidance to the university on the submission of data,[43] however, it also led to the criticism amongst faculty members of the ease with which THE's ranking system could be abused. The matter was discussed in Japan's National Diet on April 21, 2021.[44]

Seven Indian Institutes of Technology (Mumbai, Delhi, Kanpur, Guwahati, Madras, Roorkee and Kharagpur) have boycotted THE rankings from 2020. These IITs have not participated in the rankings citing concerns over transparency.[45]

World rankings[]

| Institution | 2021–22[46] | 2020–21[47] | 2019–20[48] | 2018–19[49] | 2017-18[50] | 2016–17[51] | 2015–16[52] | 2014–15[53] | 2013–14[54] | 2012–13[55] | 2011–12[56] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | |

| 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | |

| 7 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | |

| 8 | 7 | 13 | 15 | 18 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 9 | |

| 11 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 12 | |

| 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | |

| 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 17 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 14 | |

| 13 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 16 | |

| 15 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 15 | |

| 16 | 23 | 24 | 31 | 27 | 29 | 42 | 48 | 45 | 46 | 49 | |

| 16 | 20 | 23 | 22 | 30 | 35 | 47 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 71 | |

| 18 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 22 | 21 | 17 | 17 | |

| 18 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 19 | |

| 20 | 15 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 |

Young Universities[]

In addition, THE also provides 150 Under 50 Universities with different weightings of indicators to accredit the growth of institutions that are under 50 years old.[57] In particular, the ranking attaches less weight to reputation indicators. For instance, the University of Canberra Australia, established in Year 1990 at the rank 50 of 150 Under 50 Universities.

Subject[]

Various academic disciplines are sorted into six categories in THE's subject rankings: "Arts & Humanities"; "Clinical, Pre-clinical & Health"; "Engineering & Technology"; "Life Sciences"; "Physical Sciences"; and "Social Sciences".[58]

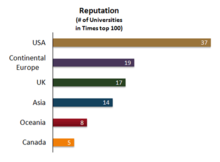

World Reputation Rankings[]

THE's World Reputation Rankings serve as a subsidiary of the overall league tables and rank universities independently in accordance with their scores in prestige.[59]

Scott Jaschik of Inside Higher Ed said of the new rankings: "...Most outfits that do rankings get criticised for the relative weight given to reputation as opposed to objective measures. While Times Higher Education does overall rankings that combine various factors, it is today releasing rankings that can't be criticised for being unclear about the impact of reputation – as they are strictly of reputation."[60]

| Institution | 2011[61] | 2012[62] | 2013[63] | 2014[64] | 2015[65] | 2016[66] | 2017[67] | 2018[68] | 2019[69] | 2020[70] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 12 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| 8 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 10 | |

| 10 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | |

| 15 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 12 | |

| 35 | 30 | 35 | 36 | 26 | 18 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | |

| 23 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 13 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 19 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| 43 | 38 | 45 | 41 | 32 | 21 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 16 | |

| 24 | 22 | 20 | 16 | 15 | 19 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 17 | |

| 19 | 21 | 20 | 25 | 17 | 20 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 18 | |

| 14 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 16 | 19 | |

| 17 | 16 | 16 | 20 | 16 | 23 | 24 | 22 | 19 | =20 | |

| 22 | 19 | 18 | 22 | 23 | 16 | 19 | 16 | 20 | =20 | |

| 11 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 22 | |

| 18 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 23 | |

| 27 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 24 | 24 | 24 | |

| 16 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 20 | 17 | 23 | 18 | 22 | 25 |

Regional rankings[]

Asia[]

From 2013 to 2015, the outcomes of the Times Higher Education Asia University Rankings were the same as the Asian universities' position on its World University Rankings. In 2016, the Asia University Rankings was revamped and it "use the same 13 performance indicators as the THE World University Rankings, but have been recalibrated to reflect the attributes of Asia's institutions."[71]

Emerging Economies[]

The Times Higher Education Emerging Economies Rankings (Formerly known as BRICS & Emerging Economies Rankings) only includes universities in countries classified as "emerging economies" by FTSE Group, including the "BRICS" nations of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Hong Kong institutions are not included in this ranking.

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Order shown in accordance with the latest result.

References[]

- ^ Elsevier. "Discover the data behind the Times Higher Education World University Rankings". Elsevier Connect. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Network, QS Asia News (2 March 2018). "The history and development of higher education ranking systems - QS WOWNEWS". QS WOWNEWS. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Strength and weakness of varsity rankings". NST Online. 14 September 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ariel Zirulnick. "New world university ranking puts Harvard back on top". The Christian Science Monitor.

Those two, as well as Shanghai Jiao Tong University, produce the most influential international university rankings out there

- ^ Indira Samarasekera & Carl Amrhein. "Top schools don't always get top marks". The Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010.

There are currently three major international rankings that receive widespread commentary: The Academic World Ranking of Universities, the QS World University Rankings and the Times Higher Education Rankings.

- ^ Philip G. Altbach (11 November 2010). "The State of the Rankings". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

The major international rankings have appeared in recent months – the Academic Ranking of World Universities, the QS World University Rankings, and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings (THE).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Andrew Trounson, "Science bias will affect local rankings" (9 June 2010). The Australian.

- ^ Bekhradnia, Bahram. "International university rankings: For good or ill?" (PDF). Higher Education Policy Institute.

- ^ Wildavsky, Ben (2010). The Great Brain Race: How Global Universities are Reshaping the World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691146898.

- ^ Baty, Phil. "New data partner for World University Rankings". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Mroz, Ann. "Leader: Only the best for the best". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Baty, Phil (10 September 2010). "Views: Ranking Confession". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ "Back to square one on the rankings front". The Australian. 17 February 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Baty, Phil. "THE World Rankings set for release on 16 September". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Indira Samarasekera and Carl Amrhein. "Top schools don't always get top marks". The Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010.

- ^ Simon Beck and Adrian Morrow (16 September 2010). "Canada's universities make the grade globally". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011.

- ^ Times Higher Education announces reforms to its World University Rankings.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "World University Rankings subject tables: Robust, transparent and sophisticated" (16 September 2010). Times Higher Education World University Rankings.

- ^ Baty, Phil. "THE unveils broad, rigorous new rankings methodology". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Phil Baty, "World University Rankings launch date revealed" (5 September 2011). Times Higher Education.

- ^ Phil Baty. "The top 200 – and the best of the rest" (13 September 2011), Times Higher Education.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2015/16". Times Higher Education. Times Higher Education. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Baty, Phil (17 August 2016). "World University Rankings 2016-2017 launch date announced". Times Higher Education. Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ THE Global Rankings: Change for the better. Times Higher Education (2011-10-06). Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ^ "GLOBAL: Crucial to measure teaching in rankings". Universityworldnews.com. 28 November 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Baty, Phil (16 August 2011). "Arts on an equal footing". Timeshighereducation.co.uk. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Faculty Area Normalization – Technical Explanation" (PDF). QS Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ "Times Higher Education announces reforms to its World University Rankings". timeshighereducation.co.uk. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Steve Smith (16 September 2010). "Pride before the fall?". Times Higher Education World University Rankings.

- ^ "Global path for the best of British," (16 September 2010). Times Higher Education World University Rankings.

- ^ "New partner for THE rankings; David Willetts joins TES Global advisory board". Times Higher Education. Times Higher Education. 27 November 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ "Global university rankings and their impact Archived 26 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine," (2011). "European University Association"

- ^ http://www.cwts.nl/TvR/documents/AvR-Language-Scientometrics.pdf

- ^ Holmes, Richard (5 September 2006). "So That's how They Did It". Rankingwatch.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ "Changingpublication patterns in the Social Sciences and Humanities 2000-2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "LSE in university league tables – External Relations Division – Administrative and academic support divisions – Services and divisions – Staff and students – Home". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ http://www.lse.ac.uk/aboutLSE/LSEinUniversityLeagueTables.aspx. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Trinity removed from rankings after data error". RTÉ.ie. 22 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Guttenplan, D. d (14 November 2010). "Questionable Science Behind Academic Rankings". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Strasser, Franz (3 June 2015). "How US students get a university degree for free in Germany". BBC News. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Rankings data row fuels push to oust university leader". University World News. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Rankings data row fuels push to oust university leader". University World News. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "衆議院インターネット審議中継". www.shugiintv.go.jp. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ https://indianexpress.com/article/india/seven-iits-continue-boycott-no-indian-institute-in-top-300-7487854

- ^ "World University Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). 25 August 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2020-2021)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2019-2020)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2018-2019)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2017-18)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2016-2017)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2015-2016)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2014-2015)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2013-2014)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2012-2013)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings (2011-2012)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Times Higher Education 150 Under 50 Rankings 2016". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ "TIMES Higher Education University Rankings by subjects (2013/14)". 13 April 2015.

- ^ John Morgan. "Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings". Times Higher Education.

- ^ Scott Jaschik. "Global Comparisons". Inside Higher Ed.

- ^ "THE World Reputation Rankings (2011)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE World Reputation Rankings (2012)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE World Reputation Rankings (2013)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE World Reputation Rankings (2014)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE World Reputation Rankings (2015)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings 2016". Times Higher Education.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). 5 June 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). 30 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings 2019". Times Higher Education (THE). July 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "World Reputation Rankings 2020". Times Higher Education (THE). 30 October 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Asia University Rankings 2016". 19 May 2016.

- ^ "THE Asia University Rankings (2013)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE Asia University Rankings (2014)". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Asia University Rankings 2015 Results". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Asia University Rankings 2017". 14 March 2017.

- ^ "Asia University Rankings 2018". 5 February 2018.

- ^ "Asia University Rankings 2019". 26 April 2019.

- ^ "Asia University Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). 28 May 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ "THE BRICS & Emerging Economies Rankings 2014". Times Higher Education. 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "THE BRICS & Emerging Economies Rankings 2015". Times Higher Education. 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ "BRICS & Emerging Economies Rankings 2016". 2 December 2015.

- ^ "Emerging Economies University Rankings 2017". 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Emerging Economies University Rankings 2018". 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Emerging Economies University Rankings 2019". 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Emerging Economies University Rankings 2020". 22 January 2020.

External links[]

- Times Higher Education World University Rankings website

- Times Higher Education - World University Rankings 2016

- Times Higher Education - BRICS and Emerging Economies University Rankings 2016

- Times Higher Education - University Rankings by Subject 2016

- The top 100 world universities 2016 – THE rankings – The Telegraph

- University rankings: UK 'a stand-out performer' – BBC

- Interactive maps comparing the Times Higher Education, Academic Ranking of World Universities and QS World University Rankings

- University and college rankings

- 2010 introductions