Tobacco and art

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

| History |

| Chemistry |

| Biology |

| Personal and social impact |

| Production |

|

Depictions of tobacco smoking in art date back at least to the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, where smoking had religious significance. The motif occurred frequently in painting of the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age, in which people of lower social class were often shown smoking pipes. In European art of the 18th and 19th centuries, the social location of people – largely men – shown as smoking tended to vary, but the stigma attached to women who adopted the habit was reflected in some artworks. Art of the 20th century often used the cigar as a status symbol, and parodied images from tobacco advertising, especially of women. Developing health concerns around tobacco smoking also influenced its artistic representation. Recently tobacco has impacted on art in a quite different way, with the conversion of many cigarette vending machines into Art-o-mat outlets, selling miniature artworks the shape and size of a cigarette packet.

Maya art[]

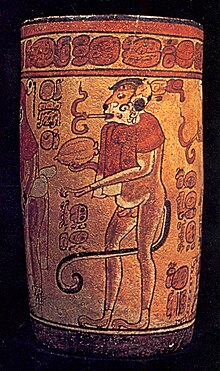

Mayas were perhaps the first people to represent tobacco smoking in art. Mayas smoked heavily, and they believed that their gods did too.[1] Religious rituals often involved tobacco: offerings were given to certain gods and tobacco smoke warded off evil deities.[1] Many tribes viewed tobacco as a supernatural, magical substance (perhaps because of its strong physiological and sometimes hallucinogenic effects).[1] Because of tobacco's significance, it is not surprising that Mayas produced artistic representations of smoking.[1] The artwork mostly portrays religious rituals and myths involving gods or lords because ordinary people and actions were considered too unimportant and unworthy for time-consuming art pieces.[2]

Numerous depictions of smoking can be found from the Classic epoch (3rd through 8th centuries). Though what substance deities and people are smoking cannot be said for certain, scholars generally conclude that the smoked substance is tobacco after studying archaeological materials.[2] The representations are occasionally confusing as the Mayas portrayed smoke and cigars in varied ways.[2] Smoke can be illustrated with black dots, black and red dots (with red indicating sparks), converging scrolls, or converging coils.[2][3] Converging scrolls also sometimes represent foliage, speech, fire, smells, and other things.[2] Cigars are usually funnel-shaped (or torch-shaped) and vary greatly in size.[2] Cigarettes (small, slender cigars in this case) resemble modern cigarettes (narrow, long rectangles) or elongated ovals.[2]

Codices[]

Mayas created codices chronicling their history and culture, and they constructed pages from copo – plant fiber on bark or deerskin with lime.[3] Though missionaries destroyed many codices, one of the remaining codices (the Codex Madrid ) contains depictions of smoking.[3] Gods smoke cigars on pages 79b, 86b, 87, and 88.[3] The Codex Madrid also contains glyphs thought to mean "smoking."[4]

Stone monuments and frescos[]

The Sanctuary of the Temple of the Cross at Palenque (a Maya city in current Mexico) houses a monument called "El Fumador" (Spanish for "The Smoker"). The stone door panel features an elderly deity blowing smoke from a large cigar. Because of the cigar's funnel shape (which compares to cigars currently used by rural South American tribes) and the outward flaring smoke, scholars believe the monument depicts a religious ritual similar to those performed by other Native American tribes.[3] No other stone monuments depicting smoking are known, but there may have been others.[3]

The only known Maya painting to depict smoking is found at Tulum (a Maya city on the Yucatán Peninsula in current Mexico). The Temple of the Diving God houses the fresco, and the painting features monsters (perhaps birds) smoking large cigars.[3]

Ceramics and other artwork[]

Mayans also portrayed smoking on ceramic objects including boxes, plates, vases, and bowls.[3] The ceramics were carved or painted multiple colors (typically black, white, and red). Important ceramics featuring smoking include the Vase of the Dancing Lord, the Reynolds vase (at the Museum of the American Indian), Plate of the Smoking God, the Woman, and the Monkey (at the National Museum of Guatemala), Vase of the Smoking Monkey, and Bowl of the Eleven Deities, Five of Them Smoking.[3]

The Vase of the Danse Macâbre depicts a smoking skeleton carrying a jar or pouch and another skeleton and two jaguars also holding pouches or jars. The carried objects are believed to hold tobacco or tobacco mixed with other substances.[3] They display the sign of darkness, so tobacco may have been associated with rituals relating to death.[3]

Though the majority of depictions show gods and lords, some artifacts portray the everyday. For example, the Plate of the Smoking Husband depicts a man smoking a cigarette and his wife rolling dough inside their home.[3]

Other artifacts depicting smoking have also been found including a shell carving, which is now housed at the Cleveland Museum of Art.[3]

Dutch art during the Golden Age[]

The ordinary person in the 17th century Dutch Republic viewed tobacco as a novelty and associated smoking with social deviance. A divide existed between the medicinal use of tobacco, which was widely accepted, and recreational use, which was seen as low class and inappropriate for more respected citizens including church and government leaders.[5] Johann Neander's Tabacologia, written in 1622, demonstrates the prevalent belief that tobacco held curative and preventative properties for a wide range of diseases.[5] However, smoking's prevalence among sailors, soldiers, and the rural poor along with its intoxicating effects led to an association with the lowliest people.[5] Thus, smoking became a tool for artists to designate someone's rank in society, and painters including Adriaen Brouwer, the Ostade brothers, and David Teniers II employed smoking in their portrayals of the low classes. Smoking also became a comedic prop for painters especially in festival and burlesque paintings.[5] Ivan Gaskell (Curator of Paintings, Sculpture, and Decorative Arts in the Harvard Art Museums) argues that "If we trace the imagery of topsy-turvydom in Dutch art we find tobacco to be a key element in scenes of comic disorder".[5]

Jan Steen, perhaps the most famous comic painter during the 17th century, often included pipe smoking, which took on sexual connotations in his paintings of brothels and taverns. For example, a man packing tobacco into a pipe along with pipes leaning against chamberpots symbolized sexual flirtations and intercourse.[5] These were often used for a comic effect, especially in illustrations of robbers stealing from intoxicated patrons of brothels and taverns. Moreover, women smoking in Steen's paintings subverted cultural norms and added an additional comic effect as men almost exclusively smoked during that time period. Short pipes, especially, implied the most debased women and the ugliest prostitutes.[5]

Moreover, pipes, especially a pair of crossed pipes, symbolized rhetoricians—guilds of actors and poets that held festivals emphasizing pleasure.[5] Several of Steen's paintings were created to illustrate proverbs including: "as the old sing, so the young pipe (soo de ouden songen, soo pijpen de jongen)" [5]—meaning the youth will pick up poor habits like smoking by imitating adults. Finally, Steen often included negative implications of smoking even when he painted smoking for a comic effect by depicting smokers next to a beggar’s crutches or whipping branches to reiterate to the viewer that smoking will lead to "punishment, poverty, and beggary".[5]

Because of economic interests in importing tobacco from the New World to Europe and even starting domestic tobacco farming, Amsterdam merchants worked to reduce smoking stigmatization.[5] By the late 17th century, smoking long-stemmed and polished pipes became acceptable for more respectable males while the lower classes smoked from cruder and shorter pipes. Snuff also gained popularity, and depictions of smoking and tobacco in paintings and drawings became more representative of the mundane and everyday than comically absurd situations and social outcasts.[5]

18th century to 21st century[]

Following the Golden Age, tobacco usage in artwork lost prominence. The decline of smoking representations is most likely due to the influence of Rococo age elegance, which made snuff the preferred choice.[6] Though snuff usage increased, snuff portrayals never became as common as those of cigars, cigarettes, and pipes in European paintings. Against norms of the time period, French artist Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, who was inspired by Golden Age artwork, occasionally included pipes in his pieces.[6] One such painting is a still life entitled Smoking Kit with Drinking Pot. The pipe in this piece lacks symbolic meaning.

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, smoking took on new and varied symbolic meanings. During this time period, men were the primary smokers, and smoking was not an acceptable habit for women who were expected to be ideal mothers or mistresses.[6] In the Romantic period, people believed smoking held a close association with intellectualism. Édouard Manet's Stéphane Mallarmé exemplifies art from this time. The painting shows an upper-class man with a lit cigar in his hand and that same hand resting on top of an open book. His eyes are look into the distance seeming to be deep in thought. Benno Tempel (director of the Kunstmuseum, The Hague) argues that smoking in this painting symbolizes a modern lifestyle even though smoking had been around for centuries.[6]

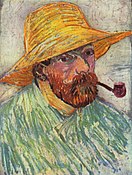

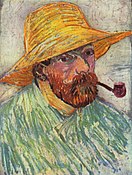

The impressionists painted scenes of everyday life that included cigars, cigarettes, or pipes, but they did not put symbolic importance in them.[6] The post-impressionists returned symbolic meaning to smoking instruments. One notable painting was done by Vincent van Gogh called Skull with a Burning Cigarette. Although this painting seems to be an anti-smoking warning, it was actually representative of the black humor and practical jokes popular during that time.[6] Edvard Munch launched this trend with his painting Self-Portrait with Cigarette. It shows the artist with a cigarette against a dark background and an eerie look across his face. Munch used smoke to symbolize psychological problems.[6]

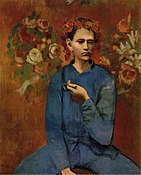

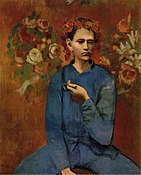

By the 20th century, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes all had their own specific meanings and connotations that developed across history. By playing off these meanings, artists conveyed a fuller understanding of an artwork to the viewer. For example, the cigar came to represent a social status symbol, and artists included cigars in paintings to show emphasize social classes and power differences. Heinrich Maria Davringhausen’s The Black Marketeer depicts a boss with a boxful of cigars and a lit one at the edge of his desk. This demonstrates the unequal social relationship between the employer and the employee.[6] Pablo Picasso also used the pipe in his piece called The Poet. This painting relies on the inseparable connection between literature and the pipe to provide the viewer with a better understanding of the painting.[6]

Pop art[]

With the rise of Pop Art, art pieces became more cynical. Pop art culture targeted clichés that evolved from the tobacco industry. Mel Ramos and Tom Wesselmann are two notable artists who poked fun at the industry.[6] Following the stigmatization of tobacco in America, pop art has shed a negative light on smoking. Claes Oldenburg’s sculpture Giant Fagends depicts how cigarette addiction exemplifies the American's wasteful consumerism.[6] Duane Hanson’s Supermarket Shopper shows a miserable middle-aged woman to represent how present day Americans view smokers: ruled by the addiction and lack will-power.[6]

Modern art[]

Various forms of modern art have also included cigarettes. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City displayed Jac Leiner's Lung in March 2009. This piece features 1200 Marlboro packs neatly folded and strung together. Leiner illustrates her own personal addiction by presenting the sickening amount of cigarettes that she unconsciously consumed over three years.[7] Another example called Why Can’t I Stop Smoking is on display at the St. Louis Art Museum. This piece portrays an incompletely painted man on a large canvas with the title of the painting written across the top. It demonstrates the addictive power of cigarettes because the artist cannot overcome the addiction to finish something that he presumably loves to do: paint.[8]

Smoking, women, and art[]

During the 17th century, Dutch paintings with women and pipes symbolized misfortune. Women in these paintings are rarely the ones in possession of the pipe, and the Dutch artists meant to send a moral message that foolish behaviors like smoking will lead people into hardships.[6]

Artwork in the 18th century included pipes to convey an exoticism and eroticism even though depictions of smoking went out of fashion in the Western World.[6] An example is Jean-Étienne Liotard’s A French Woman in Turkish Costume in a Harmam Instructing her Servant, which features a woman with a long pipe standing in a position of authority.

In the 19th century, artists, caricaturists, fine potters, and even novelists depicted women smoking. Though portrayals of women smokers became more common, they were shown in a negative light because smoking was still not acceptable for women.[9] During this time, artwork that incorporated smoking was kept in rooms reserved only for men including smoking saloons, billiard rooms, and libraries.[6] Impressionists employed pipes to distinguish males from females and emphasize their different social statuses. In Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte, the male in the white suit holds a cigar, and even in this snapshot of everyday life, there is an implicit hierarchy between him and the woman who is with him.[6]

Prostitutes were the first women in this time period to be depicted with pipes, cigars, or cigarettes as seen in artwork from Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The women used smoke and make-up (as seen from their very white faces) to attract male clients.[6] Some artists wanted to change social norms and de-stigmatize smoking for women. Frances Benjamin Johnston was one notable woman who studied illustrating for many years in Paris and then discovered photography. Her piece titled Self- Portrait depicts her holding a cigarette in one hand and a beer stein in the other. She is not dressed provocatively like most females who were associated with alcohol and cigarettes during this time. Instead, she realistically captures aspects of her life and complicates the society's understanding of middle class women.[9] Jane Atché commercially published color lithographs of women smokers without any sexual connotations. Her prints offered sophisticated woman who enjoyed cigarettes.[9]

Resulting from new representations of women smokers from artists like Frances Benjamin Johnston and Jane Atché, smoking became more socially acceptable for women. Eventually, smoking grew into a phenomenon for women. Tobacco products took on varied meanings in the 20th century. During the Roaring Twenties, women smoked cigarettes to appear chic and sophisticated.[6] Yet, paintings with female prostitutes holding with cigars took on a negative meaning because women from low classes were not meant to have objects connected with the upper class. These pieces showed women as seductresses who tricked men into giving them wealth and power.[6]

Smoking began losing its attractiveness as the 20th century progressed, and art followed this trend. Artists mocked the cigarette industry for using highly sexualized images of women in advertising.[6] Mel Ramos created artwork depicting naked women on cigars. Tom Wesselmann exploited the clichés of sex and cigarettes by painting an exposed breast behind an ashtray.[6] Present day artists acknowledge smoking as a health risk, but some want to fight modern, taboo perceptions of tobacco instead of demonizing smoking. Sarah Lucas’s photo titled "Fighting Fire with Fire" shows herself with a cigarette in the corner of her mouth. This one picture sums up the evolution of the relationship between woman, smoking, and art. According to Benno Tempel, this photo shows that "at times when society tries to create taboos, art can break through them".[6]

Art-o-mat[]

Art-o-mat machines sell pocket-size art pieces for $5.00 throughout the world. The apparatuses are converted cigarette vending machines, which are now banned in the United States. Currently, 90 machines exist with one in Quebec, one in Vienna, and the rest throughout the United States. Private businesses, cultural centers, art museums, universities, and other locations possess Art-o-mats, and they receive $1.50 for each piece sold. Some renowned sites include New York City's Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

Over three hundred artists from ten different countries have created original artwork for the machines. $2.50 goes to the artist whenever someone buys their work. The pieces come in white containers the size of a cigarette pack (roughly two inches by three inches) and wrapped in cellophane. They range from miniature sculptures to jewelry to tiny paintings. Almost every media imaginable has been used including wood, glass, watercolors on canvas, clay, Styrofoam, magnets, stained-glass, and bronze.[10] Contributing sculptor Jules Vital said, "This project gives artists the opportunity to get their work into major venues, and it's cheap for buyers.".[10]

Clark Whittington built the first machine for his 1997 art show at a café in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The original machine sold Whittington's black & white photographs for $1.00, and Cynthia Giles, the owner of the café, requested that the machine remain after the show ended. Shortly afterward, Whittington formed Artists in Cellophane (A.I.C.) with other artists from the Winston-Salem area to build more art vending machines and to create pieces for them.

Today, A.I.C. sponsors the Art-o-mat machines with the goal of increasing art consumption by packaging art in an easily accessible manner. Whittington hopes collectors will form a habit of art buying and become interested in buying larger pieces from local artists.[11] He collects the remaining $1.00 from each purchase to maintain the machines. A.I.C. seeks to unite art with consumerism and commerce and looks to expand to new locations and recruit new artists.[12]

Gallery[]

The Smoker by Adriaen van Ostade.

An Apothecary Smoking in an Interior (1646) by Adriaen van Ostade.

Resting Travelers (1671) by Adriaen van Ostade.

Man Smoking and Drinking (1859) by Frederick William Fairholt.

Jews Taking Snuff (1885) by Emanuel Salomon Friedberg-Mírohorský.

Still-life of Straw Hat and Pipe (1885) by Vincent van Gogh.

Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette (1885 or 1886) by Vincent van Gogh.

Still-life with Straw hat (1888) by Vincent van Gogh.

Monsieur Louis Pascal (1891) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Man with Pipe (1892) by Paul Cézanne.

Smoking shisha at the teashop (1892) by Enrique Simonet.

Boy with a Pipe (Garçon à la pipe) (1905) Oil on canvas by Pablo Picasso.

Self-portrait (1918) by Enrique Simonet.

Couple in a room by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

References[]

- ^ a b c d Robicsek, Francis. "Tobacco and Religion." The Smoking Gods: Tobacco in Maya Art, History, and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1978. 27–36. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robicsek, Francis. "The Classification of Archaeological Material." The Smoking Gods: Tobacco in Maya Art, History, and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1978. 111-13. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Robicsek, Francis. "Scenes Almost Certainly Representing the Act of Smoking." The Smoking Gods: Tobacco in Maya Art, History, and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1978. 114-45. Print.

- ^ Robicsek, Francis. "Tobacco and the Mayas." The Smoking Gods: Tobacco in Maya Art, History, and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1978. 11–26. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gaskell, Ivan. "Tobacco, Social Deviance, and Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century." Looking at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art: Realism Reconsidered. Ed. Wayne E. Franits. New York: Cambridge UP, 1997. 68–77. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Tempel, Benno. "Symbol and File: Smoking in Art since the Seventeenth Century." Smoke: a Global History of Smoking. Ed. Sander L. Gilman and Xun Zhou. London: Reaktion, 2004. 206–217. Print.

- ^ Brett, Guy. "Jac Leirner's Lung." Web log post. Box Vox. 2 December 2009. Web. 28 April 2010. <http://www.boxvox.net/2009/12/jac-leirners-lung.html>

- ^ Polke, Sigmar. Why Can't I Stop Smoking. 1964. Dispersion and Charcoal on Canvas. St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Dolores. "Women and Nineteenth- Century Images of Smoking." Smoke: a Global History of Smoking. Ed. Sander L. Gilman and Xun Zhou. London: Reaktion, 2004. 206–217. Print.

- ^ a b Rankine, Jerome. "Must Have: Pull Lever, Get Culture." Newsweek. Newsweek, Inc., 22 September 2003. Web. 28 April 2010. <http://www.newsweek.com/id/60175>

- ^ Cosgrove-Mather, Bootie. "Art-O-Mat Aims For Collectors." CBS News. CBS Interactive Inc., 25 February 2003. Web. 28 April 2010. <http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/02/25/national/main541998.shtml>.

- ^ "The Story behind Art-o-mat." Art-o-mat. Artists in Cellophane. Web. 28 April 2010. <http://www.artomat.org/history.html>.

- Visual arts by subject

- Tobacco