Tumu Crisis

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

Coordinates: 40°23′N 115°36′E / 40.383°N 115.600°E

| Tumu Crisis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumu Fortress Crisis | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Northern Yuan dynasty | Ming dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 approx.[citation needed] | 500,000[1] | ||||||

The Tumu Crisis (simplified Chinese: 土木之变; traditional Chinese: 土木之變; Mongolian: Тумугийн тулалдаан), was a frontier conflict between the Northern Yuan dynasty and the Ming dynasty. The Oirat ruler of the Northern Yuan, Esen Taishi, captured the Emperor Yingzong of Ming on September 1, 1449.[2]

Name[]

It was also called the Crisis of Tumu Fortress (simplified Chinese: 土木堡之变; traditional Chinese: 土木堡之變) or Battle of Tumu (Chinese: 土木之役).

Beginning of the conflict[]

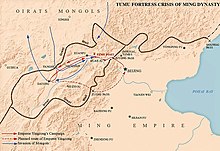

In July 1449, Esen Taishi launched a large-scale, three-pronged invasion of the Ming with his puppet khagan Toqtaq-Buqa. He personally advanced on Datong (in northern Shanxi province) in August. The eunuch official Wang Zhen, who dominated the Ming court, encouraged the 22-year-old Emperor Yingzong of Ming to lead his own armies into battle against Esen. The size of Esen's army is unknown but a best guess puts it at some 20,000 men. The Ming army of about 500,000 was hastily assembled; its command was made up of 20 experienced generals and a large entourage of high-ranking civil officials, with Wang Zhen acting as field marshal.

On August 3, Esen's army crushed a badly supplied Ming army at Yanghe, just inside the Great Wall. The same day the Emperor appointed his half-brother Zhu Qiyu as regent. The next day he left Beijing for Juyong Pass. The objective was a short, sharp march west to Datong via the Xuanfu garrison, a campaign into the steppe and then a return to Beijing by a southerly route through Yuzhou. Initially the march was mired by heavy rain. At Juyong Pass the civil officials and generals wanted to halt and send the emperor back to Beijing, but their opinions were overruled by Wang Zhen. On August 16, the army came upon the corpse-strewn battlefield of Yanghe. When it reached Datong on August 18, reports from garrison commanders persuaded Wang Zhen that a campaign into the steppe would be too dangerous. The "expedition" was declared to have reached a victorious conclusion and on August 20 the army set out back toward the Ming.[citation needed]

Wang Zhen[]

Fearing that the restless soldiers would cause damage to his estates in Yuzhou, Wang Zhen decided to strike northeast and return by the same exposed route as they had come. The army reached Xuanfu on August 27. On August 30, the Northern Yuan forces attacked the rearguard east of Xuanfu and wiped it out. Soon afterwards they also annihilated a powerful new rearguard of cavalry, led by the elderly General Zhu Yong, at Yaoerling. On August 31, the imperial army camped at the post station of Tumu. Wang Zhen refused his ministers' suggestion to have the emperor take refuge in the walled city of Huailai, just 45 km ahead.

Esen sent an advance force to cut access to water from a river south of the Ming camp. By the morning of September 1 they had surrounded the Ming army. Wang Zhen rejected any offers to negotiate and ordered the confused army to move toward the river. A battle ensued between the disorganized Ming army and the advance guard of Esen's army (Esen was not at the battle). The Ming army basically dissolved and was almost annihilated. The Northern Yuan forces captured a huge quantity of arms and armour while killing most of the Ming troops. All the high-ranking Ming generals and court officials were killed. According to some accounts, Wang Zhen was killed by his own officers. The Emperor was captured, and on September 3 he was sent to Esen's main camp near Xuanfu.

Aftermath[]

The entire expedition had been unnecessary, ill-conceived, and poorly commanded. The Northern Yuan victory was won by an advance guard of perhaps as few as 5,000 cavalry. Esen, for his part, was not prepared for the scale of his victory or for the capture of the Ming emperor. At first he attempted to use the captured emperor to raise a ransom and negotiate a favourable treaty including trade benefits.[3] However, his plan was foiled due to the steadfast leadership of the Ming commander in the capital, General Yu Qian. The Ming leaders rejected Esen's offer, Yu stating that the country was more important than an emperor's life.

The Ming never paid a ransom for the return of the Emperor, and Esen released him four years later. Esen himself faced growing criticism for his failure to exploit his victory over the Ming and he was assassinated six years after the battle in 1455.[4]

Statistics[]

The defeated Ming forces were numbered around 500,000 [5] whereas the Oirat forces numbered 20,000.[citation needed]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J. The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000-1650, Volume 1: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization Greenwood Press (January 2006) ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8 p.151 [1]

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J. The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000-1650, Volume 1: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization Greenwood Press (January 2006) ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8 p.151 [2]

- ^ Barfield 1992, p. 241.

- ^ Barfield 1992, p. 242.

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J. The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000-1650, Volume 1: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization Greenwood Press (January 2006) ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8 p.151 [3]

Works cited[]

- Barfield, Thomas J (1992). The Perilous Frontier. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell publishers. p. 242. ISBN 1-55786-043-2.

Further reading[]

- "Cambridge History of China, Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty", edited by Twitchett and Mote, 1988.

- Frederick W. Mote. "The T'u-Mu Incident of 1449." In Chinese Ways in Warfare, edited by Edward L. Dreyer, Frank Algerton Kierman and John King Fairbank. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974.

- The Perilous Frontier, Chapter 7, 'Steppe Wolves and Forest Tigers: The Ming, Mongols and Manchus', Thomas J Barfield

- Battles involving Mongolia

- Battles involving the Ming dynasty

- Great Wall of China

- 1449 in Mongolia

- 1449 in Asia

- 15th century in China

- Conflicts in 1449