Tusk

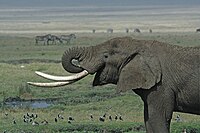

Tusks are elongated, continuously growing front teeth that protrude well beyond the mouth of certain mammal species. They are most commonly canine teeth, as with pigs and walruses, or, in the case of elephants, elongated incisors. Tusks share common features such as extra-oral position, growth pattern, composition and structure, and lack of contribution to ingestion. Tusks are thought to have adapted to the extra-oral environments, like dry or aquatic or arctic.[1] In most tusked species both the males and the females have tusks although the males' are larger. Most mammals with tusks have a pair of them growing out from either side of the mouth. Tusks are generally curved and have a smooth, continuous surface. The narwhal's straight single helical tusk, which usually grows out from the left of the mouth and is present usually in the male, is an exception to the typical features of tusks described above. Continuous growth of tusks is enabled by formative tissues in the apical openings of the roots of the teeth.[2][3] Prior to over hunting and proliferation of the ivory trade, elephant tusks weighing over 90 kg (200 lb) were not uncommon, though it is rare today to see any over 45 kg (100 lb).[4]

Other than mammals, dicynodonts are the only known vertebrates to have true tusks.[5]

Function[]

Tusks have a variety of uses depending on the animal. Social displays of dominance, particularly among males, are common, as is their use in defense against attackers. Elephants use their tusks as digging and boring tools. Walruses use their tusks to grip on ice and to haul out on ice.[6] It has been suggested that tusk's structure has evolved to be compatible with extra-oral environments.[1]

Use by humans[]

Tusks are used by humans to produce ivory, which is used in artifacts and jewellery, and formerly in other items such as piano keys. Consequently, many tusk-bearing species have been hunted commercially and several are endangered. The ivory trade has been severely restricted by the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

Unlike animal horns, animal tusks cannot be safely sawn off without hurting the animal.[7]

Gallery[]

Tusks of a Wild boar

See also[]

- Fang, a long canine tooth (in mammals)

- Ivory trade

- Eco-economic decoupling

References[]

- ^ a b Nasoori, Alireza (2020). "Tusks, the extra-oral teeth". Archives of Oral Biology. 117: 104835. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104835. PMID 32668361. S2CID 220585014. Lay summary.

- ^ "Tusk". The Oxford English Dictionary. 2010.

- ^ Konjević, Dean; Kierdorf, Uwe; Manojlović, Luka; Severin, Krešimir; Janicki, Zdravko; Slavica, Alen; Reindl, Branimir; Pivac, Igor (4 April 2006). "The spectrum of tusk pathology in wild boar (Sus scrofa L.) from Croatia" (PDF). Veterinarski Arhiv. 76 (suppl.) (S91–S100). Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "Still Life" by Bryan Christy. National Geographic Magazine, August, 2015, pp. 97, 104.

- ^ Whitney, M. R.; Angielczyk, K. D.; Peecook, B. R.; Sidor, C. A. (2021). "The evolution of the synapsid tusk: Insights from dicynodont therapsid tusk histology". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288 (1961). doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.1670. PMC 8548784. PMID 34702071.

- ^ Fay, F.H. (1985). "Odobenus rosmarus". Mammalian Species. 238 (238): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503810. JSTOR 3503810.[dead link]

- ^ "The Truth About Tusks".

- Mammal anatomy

- Bone products

- Ivory