Typographical error

A typographical error (often shortened/nicknamed to typo), also called misprint, is a mistake (such as a spelling mistake)[1] made in the typing of printed (or electronic) material. Historically, this referred to mistakes in manual type-setting (typography). Technically, the term includes errors due to mechanical failure or slips of the hand or finger,[2] but excludes errors of ignorance, such as spelling errors, or changing and misuse of words such as "than" and "then". Before the arrival of printing, the "copyist's mistake" or "scribal error" was the equivalent for manuscripts. Most typos involve simple duplication, omission, transposition, or substitution of a small number of characters.

"Fat Finger", or "Fat-Finger Syndrome" (also used in financial sectors), a slang term, refers to an unwanted secondary action when typing. When one's finger is bigger than the touch zone, there can be inaccuracy in the fine motor movements and accidents may occur. This is common with touchscreens. One may hit two adjacent keys on the keyboard in a single keystroke. An example is "buckled" instead of "bucked", due to the "L" key's being next to the "K" key on the QWERTY keyboard, the most common keyboard for Latin-script alphabets.

Marking typos[]

When using a typewriter without correction tape, typos were commonly overstruck with another character such as a slash. This saved the typist the trouble of retyping the entire page to eliminate the error, but as evidence of the typo remained, it was not aesthetically pleasing.

In computer forums, sometimes ^H (a visual representation of the ASCII backspace character) was used to "erase" intentional typos: Be nice to this fool^H^H^H^Hgentleman, he's visiting from corporate HQ.[3]

In instant messaging, users often send messages in haste and only afterwards notice the typo. It is common practice to correct the typo by sending a subsequent message in which an asterisk is placed before (or after) the correct word.[4]

In formal prose, it is sometimes necessary to quote text containing typos or other doubtful words. In such cases, the author will write "[sic]" to indicate that an error was in the original quoted source rather than in the transcription.[5]

Scribal errors[]

Scribal errors received a lot of attention in the context of textual criticism. Many of these mistakes aren't specific to manuscripts and can be referred to as typos. Some classifications include homeoteleuton and homeoarchy (skipping a line due to the similarity of the ending or beginning), haplography (copying once what appeared twice), dittography (copying twice what appeared once), contamination (introduction of extraneous elements), metathesis (reversing the order of some elements), unwitting mistranscription of similar elements, mistaking similar looking letters, substitution of homophones, fission and fusion (joining or separating words).[6][7]

Biblical errors[]

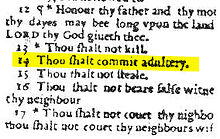

The Wicked Bible omits the word "not" in the commandment "thou shalt not commit adultery".

The Judas Bible is a copy of the second folio edition of the authorized version, printed by Robert Barker, printer to King James I, in 1613, and given to the church for the use of the Mayor of Totnes. This edition is known as the Judas Bible because in Matthew 26:36 "Judas" appears instead of "Jesus". In this copy, the mistake (in the red circle) is corrected with a slip of paper pasted over the misprint.

"Intentional" typos[]

Certain typos, or kinds of typos, have acquired widespread notoriety and are occasionally used deliberately for humorous purposes. For instance, the British newspaper The Guardian is sometimes referred to as The Grauniad due to its reputation for frequent typesetting errors in the era before computer typesetting.[8] This usage began as a running joke in the satirical magazine Private Eye.[9] The magazine continues to refer to The Guardian by this name to this day.

Typos are common on the internet in chatrooms, Usenet, and the World Wide Web, and some—such as "teh", "pwned", and "zomg"—have become in-jokes among Internet groups and subcultures. P0rn is not a typo but an example of obfuscation, where people make a word harder for robots to understand by changing it.[10]

Typosquatting[]

Typosquatting is a form of cybersquatting which relies on typographical errors made by users of the Internet.[11] Typically, the cybersquatter will register a likely typo of a frequently-accessed website address in the hope of receiving traffic when internet users mistype that address into a web browser. Deliberately introducing typos into a web page, or into its metadata, can also draw unwitting visitors when they enter these typos in Internet search engines.

An example of this is gogole.com instead of google.com which could potentially be harmful for the user.

Typos in online auctions[]

Since the emergence and popularization of online auction sites such as eBay, misspelled auction searches have quickly become lucrative for people searching for deals.[12] The concept on which these searches are based is that, if an individual posts an auction and misspells its description and/or title, regular searches will not find this auction. However, a search which includes misspelled alterations of the original search term in such a way as to create misspellings, transpositions, omissions, double strikes, and wrong key errors would find most misspelled auctions. The resulting effect is that there are far fewer bids than there would be under normal circumstances, allowing the searcher to obtain the item for less. A series of third-party websites have sprung up allowing people to find these items.[13]

Atomic typos[]

Another kind of typo—informally called an "atomic typo"—is a typo that happens to result in a correctly spelled word that is different from the intended one. Since it is spelled correctly, a simple spellchecker cannot find the mistake. The term was used at least as early as 1995 by Robert Terry.[14]

Examples include:

- "now" instead of "not",[15][16]

- "unclear" instead of "nuclear",

- "you" instead of "your",

- "Sudan" instead of "sedan" (leading to a diplomatic incident in 2005 between Sudan and the United States regarding a nuclear test code-named Sedan),

- "Untied States" instead of "United States",

- and "the" instead of "they".

See also[]

- Clerical error – Mistake in clerical work, e.g. data entry

- Comparison of web browsers – Native spell checkers are indicated in the table "Browser features".

- Fat-finger error – Keyboard input error in financial markets

- Human error – Action with unintended consequences, that is often the primary cause or contributing factor in disasters and accidents

- Orthography – Conventions when writing in a language

- Scrivener's error – Clerical error in a legal document

- Transcription error – Data entry error

References[]

- ^ "Typo - Definition". Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ "Wordnet definition". Wordnet. Princeton University. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Chapter 5. Hacker Writing Style, The Jargon File, version 4.4.7

- ^ Magnan, Sally Sieloff (2008). Mediating discourse online. AILA Applied Linguistics Series. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 260. ISBN 978-90-272-0519-3.

- ^ Wilson, Kenneth G. (1993). "sic (adv.)". The Columbia Guide to Standard American English. Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Paul D. Wegner, A student's guide to textual criticism of the Bible: its history, methods, and results, InterVarsity Press, 2006, p. 48.

- ^ "Manuscript Studies: Textual analysis (Scribal error)". www.ualberta.ca. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Ros (2000-09-12). "Internet know-how: Spelling". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (1998-02-16). "Confession as Strength At a British Newspaper". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Marsden, Rhodri (2006-10-18). "What do these strange web words mean?". The Independent. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Bob (2000-09-23). "'Typosquatters' turn flubs into cash". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ KING5 Staff (2004-07-01). "How finding mistakes can net great deals on eBay". King5. KING-TV. Archived from the original on 2007-12-20. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Douglas Quenqua (2008-11-23). "Help for eBay Shoppers Who Can't Spell". The New York Times.

- ^ Hanif, C. B. (August 10, 1995). "Hurricane Coverage Kicks Up Dust". The Palm Beach Post. p. 14. Retrieved January 25, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Callan, Tim (2011-04-23). "The now vs. not typo". Tim Callan on Marketing and Technology. Retrieved 2021-08-13.

- ^ Karr, Phyllis Ann (2012). Frostflower and Thorn. Wildside Press. p. 415. ISBN 9781479490028.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Typographic errors. |

External links[]

- "Spell checkers developing 'atomic typo' capabilities" - OpEd in the China Post, Taiwan, September 30, 2012.[dead link]

- BookErrata.com

- Error

- Typing

- Typography

- Printing terminology

- Nonstandard spelling