Wicked Bible

| |

| Original title | The Holy Bible |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Robert Barker and Martin Lucas |

Publication date | 1631 |

| Media type | |

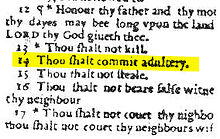

The Wicked Bible, sometimes called the Adulterous Bible or the Sinners' Bible, is an edition of the Bible published in 1631 by Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, the royal printers in London, meant to be a reprint of the King James Bible. The name is derived from a mistake made by the compositors: in the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20:14, the word "not" was omitted from the sentence "Thou shalt not commit adultery," causing the verse to instead read "Thou shalt commit adultery."

Background[]

Historically, the omission of "not" was considered quite a common mistake.[citation needed] Until 2004, for example, the style guide of the Associated Press advised using "innocent" instead of "not guilty" to describe acquittals, so as to prevent this eventuality.[1]

Errors[]

There are two significant errors in the Wicked Bible. The first error is the omission of the word "not" in the sentence "Thou shalt not commit adultery" (Exodus 20:14), thus changing the sentence into "Thou shalt commit adultery". The second error appears in Deuteronomy 5, where the word "greatness" was reportedly misprinted as "great-asse", leading to a sentence reading: "Behold, the Lord our God hath shewed us his glory and his great-asse".[2][3] The existence of this second mistake is attested as early as 1886, in the Reports of Cases in the Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission, which gives the Rawlinson MS, A128 in the Bodleian Library as the source of the claim.[4] Gordon Campbell notes that there are no surviving copies of the book that contain the second error ("great-asse"), but that in three of the surviving copies there is an inkblot positioned where the missing "n" would be, suggesting such a mistake may have been covered up in these copies. Campbell also highlights the fact that, at the time of the Wicked Bible's publication, the word "asse" only had the sense of "donkey".[5]

About a year after publication, Barker and Lucas were called to the Star Chamber and fined £300 (equivalent to £50,322 in 2019) and deprived of their printing license.[6]

Diana Severance, director of the Dunham Bible Museum at the Houston Baptist University, and Gordon Campbell have suggested that the potential second error could indicate that someone (possibly a rival printer) purposefully sabotaged the printing of the Wicked Bible so that Robert Barker and Martin Lucas would lose their exclusive license to print the Bible.[2][3][5] However, Campbell also notes that neither Barker nor Lucas suggested the possibility of sabotage in their defence when they were arraigned.[5]

The Wicked Bible is the most prominent example of the bible errata which often have absent negatives that completely reverse the scriptural meaning.[7]

Public reaction[]

The case of the Wicked Bible was commented on by Peter Heylyn in 1668:

His Majesties Printers, at or about this time [1632], had committed a scandalous mistake in our English Bibles, by leaving out the word Not in the Seventh Commandment. His Majesty being made acquainted with it by the Bishop of London, Order was given for calling the Printers into the High-Commission where upon the Evidence of the Fact, the whole Impression was called in, and the Printers deeply fined, as they justly merited.[8]

The majority of the Wicked Bible's copies were immediately cancelled and destroyed, and the number of extant copies remaining today, which are considered highly valuable by collectors, is thought to be relatively low.[9]

The fact that this edition of the Bible contained the flagrant mistakes ("great asse" and "Thou shalt commit adultery") in the Ten Commandments angered the Archbishop of Canterbury.[10]

Origin of the name[]

The nickname Wicked Bible seems to have first been applied in 1855 by rare book dealer Henry Stevens. As he relates in his memoir of James Lenox, after buying what was then the only known copy of the 1631 octavo Bible for fifty guineas, "on June 21, I exhibited the volume at a full meeting of the Society of Antiquaries of London, at the same time nicknaming it 'The Wicked Bible,' a name that has stuck to it ever since."[11]

Remaining copies[]

The majority of the Wicked Bible's copies were immediately cancelled and destroyed, and the number of extant copies remaining today, which are considered highly valuable by collectors, is thought to be relatively low.[9] One copy is in the collection of rare books in the New York Public Library and is very rarely made accessible; another can be seen in the Dunham Bible Museum in Houston, Texas, US.[12] The British Library in London had a copy on display, opened to the misprinted commandment, in a free exhibition until September 2009.[13] The Wicked Bible also appeared on display for a limited time at the Ink and Blood Exhibit in Gadsden, Alabama, from 15 August to 2 September 2009. A copy was also displayed until 18 June 2011 at the Cambridge University Library exhibition in England, for the 400th anniversary of the King James Version.

There are fifteen known copies of the Wicked Bible today in the collections of museums and libraries in the British Isles, North America and Australia:[14]

- British Isles (seven copies)

- The British Library

- University of Glasgow Library

- University of Leicester David Wilson Library[15]

- Cambridge University Library[16]

- University of Oxford, Bodleian Library

- University of Manchester, John Rylands Library

- The Library at York Minster[17]

- North America (seven copies)

- New York Public Library

- Yale University, Sterling Memorial Library

- Houston Baptist University, Dunham Bible Museum[2]

- DC Museum of the Bible

- University of Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

- The Lilly Library, Indiana University[18]

- Princeton University Library, Special Collections

- Australia (one copy)

- University of Adelaide, Rare Books and Special Collections

A number of copies also exist in private collections. In 2008, a copy of the Wicked Bible went up for sale online, priced at $89,500.[19] A second copy was put up for sale from the same website which was priced at $99,500 as of 2015.[20] Both copies were sold for around the asking price.

In 2014, William Scheide donated his library of rare books and manuscripts to Princeton University, with a copy of the Wicked Bible among its holdings.

In 2015, one of the remaining Bible copies was put on auction by Bonhams,[21] and sold for £31,250.[22]

In 2016, a copy of the Wicked Bible was put on auction by Sotheby's and sold for $46,500.[23] In 2018, the same copy of the Wicked Bible was put on auction again by Sotheby's, and sold for $56,250.[24]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Stockdale, Nicole (12 May 2004). "AP style updates". A Capital Idea. Blogspot. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brown, DeNeen. "New museum's 'Wicked Bible': Thou Shalt Commit Adultery". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ""Thou Shalt Commit Adultery: A rare copy of the so-called Wicked Bible of 1631, which omitted a rather important "not" from the 10 Commandments, is going on auction in the U.K." The Atlantic. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Rawson Gardiner, Samuel (1886). Reports of Cases in the Courts of Star Chamber and High Commission. Nichols and Sons. p. 305. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Campbell, Gordon (2010). Bible: The Story of the King James Version 1611 — 2011. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199693016. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Kohlenberger, III, John R (2008). NIV Bible Verse Finder. Grand Rapids MI: Zondervan. p. viii. ISBN 978-0310292050.

- ^ Russell, Ray (October 1980). "The Wicked Bibles". Theology Today. 37 (3): 360–363. doi:10.1177/004057368003700311. S2CID 170449311.

- ^ "Challenges in Printing Early English Bibles | Religious Studies Center". rsc.byu.edu.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gekoski, Rick (23 November 2010). "The Wicked Bible: the perfect gift for collectors, but not for William and Kate". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Ingelbart, Louis Edward (1987). Press Freedoms. A Descriptive Calendar of Concepts, Interpretations, Events, and Courts Actions, from 4000 B.C. to the Present, p. 40, Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-313-25636-5

- ^ Stevens, Henry. Recollections of Mr James Lenox of New York and the Formation of His Library. London: Henry Stevens & Son, 1886 (page 35).

- ^ Turner, Allan. "Historic Bibles ‑ even a naughty one ‑ featured at Houston's Dunham Museum". Houston Chronicle. Hearst Newspapers. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Wicked Bible on free public display in British Library, London

- ^ "English Short Title Catalogue". www.estc.bl.uk. ESTC system number 006195643, ESTC Citation Number S161

- ^ Dixon, Simon. "Who owned the Wicked Bible?". Library of Special Collections. University of Leicester. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ "University of Cambridge". University of Cambridge. iDiscover. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Stephen Lewis (29 November 2008). "The treasures of York Minster Library". York Press. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "The Wicked Bible". WorldCat. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Greatsite.com platinum room Archived 2008-06-20 at WebCite retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ "Platinum Room". December 15, 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-12-16.

- ^ Flood, Alison (21 October 2015). "Extremely rare Wicked Bible goes on sale". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ "Bonhams : BIBLE, IN ENGLISH, AUTHORIZED VERSION [The Holy Bible: Containing the Old Testament and the New], THE 'WICKED BIBLE', 2 parts in 1 vol., Robert Barker... and by the assignes of John Bill, 1631". www.bonhams.com.

- ^ "Bible in English [The "Wicked" Bible]". www.sothebys.com.

- ^ "Bible in English [The "Wicked" Bible]". www.sothebys.com.

Bibliography[]

- Eisenstein, Elisabeth L Rewolucja Gutenberga, translated by: Henryk Hollender, Prószyński i S-ka publishing, Warsaw 2004, ISBN 83-7180-774-0

- Ingelbart, Louis Edward. Press Freedoms. A Descriptive Calendar of Concepts, Interpretations, Events, and Courts Actions, from 4000 B.C. to the Present, Greenwood Publishing 1987, ISBN 0-313-25636-5

- Stevens, Henry. ′The Wicked Bible,′ in Recollections of Mr James Lenox of New York and the Formation of His Library. London: Henry Stevens & Son, 1886 (pages 34–42).

- 1631 books

- Early printed Bibles

- Linguistic error