Vasculitis

| Vasculitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vasculitides[1] |

| |

| Petechia and purpura on the lower limb due to medication-induced vasculitis. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Rheumatology, Immunology |

| Symptoms | Weight loss, fever, myalgia, purpura |

| Complications | Gangrene, Myocardial infarction |

Vasculitis is a group of disorders that destroy blood vessels by inflammation.[2] Both arteries and veins are affected. Lymphangitis (inflammation of lymphatic vessels) is sometimes considered a type of vasculitis.[3] Vasculitis is primarily caused by leukocyte migration and resultant damage. Although both occur in vasculitis, inflammation of veins (phlebitis) or arteries (arteritis) on their own are separate entities.

Signs and symptoms[]

Possible signs and symptoms include:[4]

- General symptoms: Fever, unintentional weight loss

- Skin: Palpable purpura, livedo reticularis

- Muscles and joints: Muscle pain or inflammation, joint pain or joint swelling

- Nervous system: Mononeuritis multiplex, headache, stroke, tinnitus, reduced visual acuity, acute visual loss

- Heart and arteries: Heart attack, high blood pressure, gangrene

- Respiratory tract: Nose bleeds, bloody cough, lung infiltrates

- GI tract: Abdominal pain, bloody stool, perforations (hole in the GI tract)

- Kidneys: Inflammation of the kidney's filtration units (glomeruli)

Cause[]

Classification[]

Vasculitis can be classified by the cause, the location, the type of vessel or the size of vessel.

- Underlying cause. For example, the cause of syphilitic aortitis is infectious (aortitis simply refers to inflammation of the aorta, which is an artery.) However, the causes of many forms of vasculitis are poorly understood. There is usually an immune component, but the trigger is often not identified. In these cases, the antibody found is sometimes used in classification, as in ANCA-associated vasculitides. Clinical studies with immunosuppressive drugs targeting specific cytokines and cells can also be used to understand the heterogeneous immunopathogenic mechanisms of vasculitis and support a mechanistic immunological classification.[5]

- Location of the affected vessels. For example, ICD-10 classifies "vasculitis limited to skin" with skin conditions (under "L"), and "necrotizing vasculopathies" (corresponding to systemic vasculitis) with musculoskeletal system and connective tissue conditions (under "M"). Arteritis/phlebitis on their own are classified with circulatory conditions (under "I").

- Type or size of the blood vessels that they predominantly affect.[6] Apart from the arteritis/phlebitis distinction mentioned above, vasculitis is often classified by the caliber of the vessel affected. However, there can be some variation in the size of the vessels affected.

A small number have been shown to have a genetic basis. These include adenosine deaminase 2 deficiency and haploinsufficiency of A20.

According to the size of the vessel affected, vasculitis can be classified into:[7][8]

- Large vessel: Takayasu's arteritis, Temporal arteritis

- Medium vessel: Buerger's disease, Kawasaki disease, Polyarteritis nodosa

- Small vessel: Behçet's syndrome, Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Cutaneous vasculitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and microscopic polyangiitis. Condition of some disorders have vasculitis as their main feature. The major types are given in the table below:

| Comparison of major types of vasculitis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vasculitis | Affected organs | Histopathology |

| Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis | Skin, kidneys | Neutrophils, fibrinoid necrosis |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Nose, lungs, kidneys | Neutrophils, giant cells |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Lungs, kidneys, heart, skin | Histiocytes, eosinophils |

| Behçet's disease | Commonly sinuses, brain, eyes and skin; can affect other organs such as lungs, kidneys, joints | Lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils |

| Kawasaki disease | Skin, heart, mouth, eyes | Lymphocytes, endothelial necrosis |

| Buerger's disease | Leg arteries and veins (gangrene) | Neutrophils, granulomas |

| "Limited" granulomatosis with polyangiitis vasculitis | Commonly sinuses, brain, and skin; can affect other organs such as lungs, kidneys, joints; | |

Takayasu's arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa and giant cell arteritis mainly involve arteries and are thus sometimes classed specifically under arteritis.

Furthermore, there are many conditions that have vasculitis as an accompanying or atypical feature, including:

- Rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis

- Cancer, such as lymphomas

- Infections, such as hepatitis C

- Exposure to chemicals and drugs, such as amphetamines, cocaine, and anthrax vaccines which contain the Anthrax Protective Antigen as the primary ingredient. Sympathomimetics such as phenylpropanolamine, methylphenidate, and others are also implicated.

In pediatric patients varicella inflammation may be followed by vasculitis of intracranial vessels. This condition is called post varicella angiopathy and this may be responsible for arterial ischaemic strokes in children.[9]

Several of these vasculitides are associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.[10] These are:

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Microscopic polyangiitis

Diagnosis[]

- Laboratory tests of blood or body fluids are performed for patients with active vasculitis. Their results will generally show signs of inflammation in the body, such as increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), anemia, increased white blood cell count and eosinophilia. Other possible findings are elevated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) levels and hematuria.

- Other organ functional tests may be abnormal. Specific abnormalities depend on the degree of various organs involvement. A Brain SPECT can show decreased blood flow to the brain and brain damage.

- The definite diagnosis of vasculitis is established after a biopsy of involved organ or tissue, such as skin, sinuses, lung, nerve, brain, and kidney. The biopsy elucidates the pattern of blood vessel inflammation.

- Some types of vasculitis display leukocytoclasis, which is vascular damage caused by nuclear debris from infiltrating neutrophils.[11] It typically presents as palpable purpura.[11] Conditions with leucocytoclasis mainly include hypersensitivity vasculitis (also called leukocytoclastic vasculitis) and cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis (also called cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis).

- An alternative to biopsy can be an angiogram (x-ray test of the blood vessels). It can demonstrate characteristic patterns of inflammation in affected blood vessels.

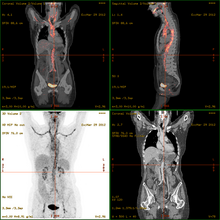

- 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT)has become a widely used imaging tool in patients with suspected Large Vessel Vasculitis, due to the enhanced glucose metabolism of inflamed vessel walls.[12] The combined evaluation of the intensity and the extension of FDG vessel uptake at diagnosis can predict the clinical course of the disease, separating patients with favourable or complicated progress.[13]

- Acute onset of vasculitis-like symptoms in small children or babies may instead be the life-threatening purpura fulminans, usually associated with severe infection.

| Disease | Serologic test | Antigen | Associated laboratory features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | ANA including antibodies to dsDNA and ENA [including SM, Ro (SSA), La (SSB), and RNP] | Nuclear antigens | Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, Coombs' test, complement activation: low serum concentrations of C3 and C4, positive immunofluorescence using Crithidia luciliae as substrate, antiphospholipid antibodies (i.e. anticardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant, false-positive VDRL) |

| Goodpasture's disease | Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody | Epitope on noncollagen domain of type IV collagen | |

| Small vessel vasculitis | |||

| Microscopic polyangiitis | Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | Myeloperoxidase | Elevated CRP |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiiitis | Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | Proteinase 3 (PR3) | Elevated CRP |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody in some cases | Myeloperoxidase | Elevated CRP and eosinophilia |

| IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura) | None | ||

| Cryoglobulinemia | Cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor, complement components, hepatitis C | ||

| Medium vessel vasculitis | |||

| Classical polyarteritis nodosa | None | Elevated CRP and eosinophilia | |

| Kawasaki's Disease | None | Elevated CRP and ESR |

In this table: ANA = Antinuclear antibodies, CRP = C-reactive protein, ESR = Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, dsDNA = double-stranded DNA, ENA = extractable nuclear antigens, RNP = ribonucleoproteins; VDRL = Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

Treatment[]

Treatments are generally directed toward stopping the inflammation and suppressing the immune system. Typically, corticosteroids such as prednisone are used. Additionally, other immune suppression medications, such as cyclophosphamide and others, are considered. In case of an infection, antimicrobial agents including cephalexin may be prescribed. Affected organs (such as the heart or lungs) may require specific medical treatment intended to improve their function during the active phase of the disease.

References[]

- ^ "Vasculitis - Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Glossary of dermatopathological terms. DermNet NZ". Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Vasculitis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ "The Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center - Symptoms of Vasculitis". Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ Torp, Christopher Kirkegaard; Brüner, Mads; Keller, Kresten Krarup; Brouwer, Elisabeth; Hauge, Ellen-Margrethe; McGonagle, Dennis; Kragstrup, Tue Wenzel (2021). "Vasculitis therapy refines vasculitis mechanistic classification". Autoimmunity Reviews. 20 (6): 102829. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102829. PMID 33872767.

- ^ Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. (1994). "Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference". Arthritis Rheum. 37 (2): 187–92. doi:10.1002/art.1780370206. PMID 8129773.

- ^ "Overview of Vasculitis". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Gündüz, Özgür (18 October 2011). "Histopathological Evaluation of Behçet's Disease and Identification of New Skin Lesions". Pathology Research International. 2012: 209316. doi:10.1155/2012/209316. ISSN 2090-8091. PMC 3199096. PMID 22028988.

- ^ Nita R Sutay, Md Ashfaque Tinmaswala, Shilpa Hegde . "International Journal of Medical Research and Health Sciences | 404 Page". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Millet A, Pederzoli-Ribeil M, Guillevin L, Witko-Sarsat V, Mouthon L (2013) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides: is it time to split up the group? Ann Rheum Dis

- ^ a b A Brooke W Eastham, Ruth Ann Vleugels and Jeffrey P Callen (12 July 2021). "Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis". Medscape. Updated: Oct 25, 2018

- ^ Maffioli L, Mazzone A (2014). "Giant-Cell Arteritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica". NEJM. 371 (17): 1652–1653. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1409206. PMC 4277693. PMID 25337761.

- ^ Dellavedova L, Carletto M, Faggioli P, Sciascera A, Del Sole A, Mazzone A, Maffioli LS (2015). "The prognostic value of baseline 18F-FDG PET/CT in steroid-naïve large-vessel vasculitis: introduction of volume-based parameters". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 55 (2): 340–8. doi:10.1007/s00259-015-3148-9. PMID 26250689. S2CID 21446786.

- ^ Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE (2012). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics, 5th edition. Elsevier Saunders. p. 1568. ISBN 978-1-4160-6164-9.

External links[]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

- Rheumatology

- Inflammations

- Vascular-related cutaneous conditions