Very Large Array

| |

| Alternative names | VLA |

|---|---|

| Named after | Karl Guthe Jansky, size, antenna array |

| Part of | NRAO VLA Sky Survey |

| Location(s) | Socorro County, New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 34°04′43″N 107°37′04″W / 34.0787492°N 107.6177275°WCoordinates: 34°04′43″N 107°37′04″W / 34.0787492°N 107.6177275°W |

| Organization | National Radio Astronomy Observatory |

| Altitude | 2,124 m (6,969 ft) |

| Wavelength | 0.6 cm (50 GHz)–410 cm (73 MHz) |

| Built | 1973–1980 |

| Telescope style | list of types of interferometers radio telescope radio interferometer |

| Diameter | |

| Angular resolution | 120 ±80 milliarcsecond |

| Collecting area | 13,250 m2 (142,600 sq ft) |

| Website | science |

Location of the Very Large Array | |

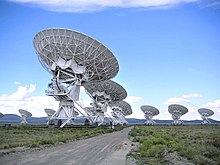

The Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) is a centimeter-wavelength radio astronomy observatory located in central New Mexico on the Plains of San Agustin, between the towns of Magdalena and Datil, ~50 miles (80 km) west of Socorro. The VLA comprises twenty-eight 25-meter radio telescopes (27 of which are operational while one is always rotating through maintenance) deployed in a Y-shaped array and all the equipment, instrumentation, and computing power to function as an interferometer. Each of the massive telescopes is mounted on double parallel railroad tracks, so the radius and density of the array can be transformed to adjust the balance between its angular resolution and its surface brightness sensitivity.[2] Astronomers using the VLA have made key observations of black holes and protoplanetary disks around young stars, discovered magnetic filaments and traced complex gas motions at the Milky Way's center, probed the Universe's cosmological parameters, and provided new knowledge about the physical mechanisms that produce radio emission.

The VLA stands at an elevation of 6,970 feet (2,120 m) above sea level. It is a component of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO).[3] The NRAO is a facility of the National Science Foundation operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

Characteristics[]

The radio telescope comprises 27 independent antennas in use at a given time plus one spare, each of which has a dish diameter of 25 meters (82 feet) and weighs 209 metric tons (230 short tons).[4] The antennas are distributed along the three arms of a track, shaped in a wye (or Y) -configuration, (each of which measures 21 kilometres (13 mi) long). Using the rail tracks that follow each of these arms—and that, at one point, intersect with U.S. Route 60 at a level crossing—and a specially designed lifting locomotive ("Hein's Trein"),[5] the antennas can be physically relocated to a number of prepared positions, allowing aperture synthesis interferometry with up to 351 independent baselines: in essence, the array acts as a single antenna with a variable diameter. The angular resolution that can be reached is between 0.2 and 0.04 arcseconds.[6]

There are four commonly used configurations, designated A (the largest) through D (the tightest, when all the dishes are within 600 metres (2,000 ft) of the center point). The observatory normally cycles through all the various possible configurations (including several hybrids) every 16 months; the antennas are moved every three to four months. Moves to smaller configurations are done in two stages, first shortening the east and west arms and later shortening the north arm. This allows for a short period of improved imaging of extremely northerly or southerly sources.[citation needed]

The frequency coverage is 74 MHz to 50 GHz (400 cm to 0.7 cm).[7]

The Pete V. Domenici Science Operations Center (DSOC) for the VLA is located on the campus of the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology in Socorro, New Mexico. The DSOC also serves as the control center for the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), a VLBI array of ten 25-meter dishes located from Hawaii in the west to the U.S. Virgin Islands in the east that constitutes the world's largest dedicated, full-time astronomical instrument.[8]

Upgrade and renaming[]

In 2011, a decade-long upgrade project resulted in the VLA expanding its technical capacities by factors of up to 8,000. The 1970s-era electronics were replaced with state-of-the-art equipment. To reflect this increased capacity, VLA officials asked for input from both the scientific community and the public in coming up with a new name for the array, and in January 2012 it was announced that the array would be renamed the "Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array".[9][10][11] On March 31, 2012, the VLA was officially renamed in a ceremony inside the Antenna Assembly Building.[12]

Key science[]

The VLA is a multi-purpose instrument designed to allow investigations of many astronomical objects, including radio galaxies, quasars, pulsars, supernova remnants, gamma-ray bursts, radio-emitting stars, the sun and planets, astrophysical masers, black holes, and the hydrogen gas that constitutes a large portion of the Milky Way galaxy as well as external galaxies. In 1989 the VLA was used to receive radio communications from the Voyager 2 spacecraft as it flew by Neptune.[13] A search of the galaxies M31 and M32 was conducted in December 2014 through January 2015 with the intent of quickly searching trillions of systems for extremely powerful signals from advanced civilizations.[14]

It has been used to carry out several large surveys of radio sources, including the NRAO VLA Sky Survey and Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters.

In September 2017 the (VLASS) began.[15] This survey will cover the entire sky visible to the VLA (80% of the Earth's sky) in three full scans.[16] Astronomers expect to find about 10 million new objects with the survey — four times more than what is presently known.[16]

History[]

The driving force for the development of the VLA was David S. Heeschen. He is noted as having "sustained and guided the development of the best radio astronomy observatory in the world for sixteen years."[17] Congressional approval for the VLA project was given in August 1972, and construction began some six months later. The first antenna was put into place in September 1975 and the complex was formally inaugurated in 1980, after a total investment of US$78,500,000 (equivalent to $246,564,822 in 2020).[7] It was the largest configuration of radio telescopes in the world.

With a view to upgrading the venerable 1970s technology with which the VLA was built, the VLA has evolved into the Expanded Very Large Array (EVLA). The upgrade has enhanced the instrument's sensitivity, frequency range, and resolution with the installation of new hardware at the San Agustin site. A second phase of this upgrade may add up to eight additional dishes in other parts of the state of New Mexico, up to 190 miles (300 km) away, if funded.[18]

Magdalena Ridge Observatory is a new observatory under construction a few miles south of the VLA. It includes an optical interferometer and is run by VLA collaborator New Mexico Tech.

Tourism[]

The VLA is located between the towns of Magdalena and Datil, about 50 miles (80 km) west of Socorro, New Mexico. U.S. Route 60 passes east–west through the complex.[citation needed]

The VLA site is open to visitors year round during daylight hours, and on every first and third Saturdays of the month, special guided and behind-the-scenes tours are offered. A visitor center houses a small museum, theater, and a gift shop. A self-guided walking tour is available, as the visitor center is not staffed continuously. Visitors unfamiliar with the area are warned that there is little food on site, or in the sparsely populated surroundings; those unfamiliar with the high desert are warned that the weather is quite variable, and can remain cold into April.[3] For those who cannot travel to the site, the NRAO created a virtual tour of the VLA called the VLA Explorer.[19]

In popular culture[]

The VLA has appeared repeatedly in American popular culture since its construction.

- The VLA is present in the 1984 movie 2010: The Year We Make Contact, as the location where Dr. Floyd and Dimitri Moiseyevich discuss the upcoming missions to Jupiter.[20]

- The VLA is present in the 1997 movie Contact, as the location where the alien signal is first detected.[20][21]

- British artist Keith Tyson created a 300 piece sculpture called Large Field Array (2006–2007) named after the VLA.[22]

- In the 2009 science-fiction film Terminator Salvation, the VLA is the location of a Skynet facility. At the beginning of the film the site is attacked by Resistance forces.[20][23]

See also[]

- Allen Telescope Array (ATA)

- Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA)

- Green Bank Telescope (GBT)

- List of radio telescopes

- Square Kilometre Array (SKA)

- Very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI)

- Very Small Array (VSA)

References[]

- ^ "VLA Antennas and The Barn". Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ http://www.vla.nrao.edu

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Visit the VLA". public.nrao.edu. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ "Welcome to the Very Large Array!". vla.nrao.edu. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ Holley, Joe (May 29, 2008). "Hein Hvatum, 85; Engineered Telescope to the Heavens". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ https://public.nrao.edu/telescopes/vla/vla-basics

- ^ Jump up to: a b "An Overview of the Very Large Array". vla.nrao.edu. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ "Very Long Baseline Array". science.nrao.edu. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ "New Mexico Radio Telescope Seeking New Name". ABC News. Associated Press. October 14, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-10-16.

- ^ Palmer, Jason (October 15, 2011). "Very Large Array telescope in public call for new name". BBC News. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ Finley, Dave. "Iconic Telescope Renamed to Honor Founder of Radio Astronomy". NRAO.edu. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ Finley, Dave. "Famous Radio Telescope Officially Gets New Name". NRAO.edu. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ Taylor, Jim, ed. (2016). Deep Space Communications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-119-16902-4.

- ^ Gray, Robert H.; Mooley, Kunal (14 February 2017). "A VLA Search for Radio Signals from M31 and M33". The Astronomical Journal. 153 (3): 110. arXiv:1702.03301. Bibcode:2017AJ....153..110G. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/153/3/110.

- ^ Murphy, Davis. "VLA Sky Survey". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barbuzano, Javier. "Iconic Radio Telescope Begins 7-year Search for New Objects". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Tucker, Wallace; Tucker, Karen (1986). The Cosmic Inquirers: Modern Telescopes and Their Makers. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674174356.

- ^ "The Expanded Very Large Array Project: A Radio Telescope to Resolve Cosmic Evolution". aoc.nrao.edu. National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ "The VLA Explorer". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Howard Hughes (30 May 2014). Outer Limits: The Filmgoers' Guide to the Great Science-fiction Films. I.B.Tauris. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-78076-166-4.

- ^ Guidebook for the Scientific Traveler. Rutgers University Press. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-8135-4918-7.

- ^ Robinson, Walter (November 11, 2007). "Weekend Update". Artnet.com. Artnet Worldwide Corporation. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

- ^ Joseph T. Page II (6 May 2013). New Mexico Space Trail. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-1-4396-4328-0.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Very Large Array. |

- Astronomical observatories in New Mexico

- Buildings and structures in Socorro County, New Mexico

- Interferometric telescopes

- Museums in Socorro County, New Mexico

- Radio telescopes

- Science museums in New Mexico

- 1980 establishments in New Mexico