Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus

"Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus" is a line from an editorial by Francis Pharcellus Church called "Is There a Santa Claus?" which appeared in The Sun on September 21, 1897, and became one of the most famous editorials ever published. Written in response to a letter by eight-year-old Virginia O'Hanlon asking whether Santa Claus was real, the editorial was initially published anonymously, and Church's authorship was not disclosed until his 1906 death. The Sun gradually accepted its popularity and republished it during the Christmas season every year from 1924 to 1950, when the paper ceased publication.

"Is There a Santa Claus?" is commonly reprinted during the Christmas and holiday season, and has been cited as the most reprinted newspaper editorial in the English language. It has been translated into around 20 languages, and adapted as a film, television presentations, a musical, and a cantata.

Background[]

Francis Pharcellus Church[]

Francis Pharcellus Church (February 22, 1839 – April 11, 1906) was an American publisher and editor. He and his brother, William Conant Church, founded and edited several publications: The Army and Navy Journal (1863), The Galaxy (1866), and the Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal (1870). Before the outbreak of the American Civil War he had worked in journalism, first at his father's New-York Chronicle and later at The Sun. Church had returned to The Sun to work part-time in 1874 and after The Galaxy merged with The Atlantic Monthly in 1878 he joined the paper's staff full-time as an editor and writer. Church wrote thousands of editorials at the paper,[1] and became known for his writing on religious topics from a secular point of view.[2][3] After Church's death, his friend J. R. Duryee wrote that he would not reveal the authorship of editorials anonymously published in The Sun and that Church "by nature and training was reticent about himself, highly sensitive and retiring".[4]

The Sun[]

In 1897 The Sun was one of the most prominent newspapers in New York City, having been developed by its longtime editor, Charles Anderson Dana, over the past thirty years.[5] Their editorials that year have been described by scholar W. Joseph Campbell as favoring "vituperation and personal attack" and the paper as reluctant to republish content.[6]

Writing and publication[]

In 1897, Philip O'Hanlon, a coroner's assistant, was asked by his then eight-year-old daughter, Virginia O'Hanlon, whether Santa Claus really existed. O'Hanlon suggested she write to The Sun. In her letter, Virginia wrote that her father had told her "If you see it in The Sun it's so."[7][a] O'Hanlon later said that she had waited for an answer to her letter for long enough that she "forgot about it." Campbell theorizes that it had been sent shortly after O'Hanlon's birthday in July and "overlooked or misplaced" for a time.[9] The Sun's editor-in-chief, Edward Page Mitchell, gave the letter to Francis Church.[10] Mitchell reported that Church, who was initially reluctant to write a response, produced it "in a short time"[1] during an afternoon.[11]

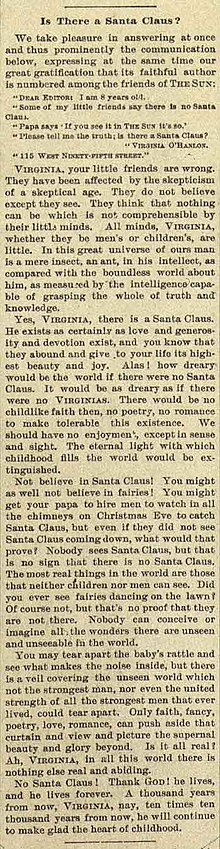

Church's response was 416 words long[12] and was anonymously[13] published in The Sun on September 21, 1897,[14] shortly after the beginning of the school year in New York City.[15] The editorial appeared in the paper's third and last editorial column that day, positioned below discussions of topics including Connecticut's election law, a newly invented chainless bicycle, and "British Ships in American Waters".[14] Dana described Church's article as "[r]eal literature," and said, "[m]ight be a good idea to reprint it every Christmas—yes, and even tell who wrote it!"[10] It drew no commentary from contemporary New York newspapers.[16]

Summary[]

The editorial, as it first appeared in The Sun, was prefaced with the text of Virginia's letter asking the paper to tell her the truth; "is there a Santa Claus?" Church's response began: "Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age." He continued to write that Santa Claus existed "as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist" and that the world would be "dreary" if he did not. Church argued that just because something could not be seen did not mean it was not real: "Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world." He concluded that:[17]

You may tear apart the baby’s rattle and see what makes the noise inside, but there is a veil covering the unseen world which not the strongest man, nor even the united strength of all the strongest men that ever lived, could tear apart. Only faith, fancy, poetry, love, romance, can push aside that curtain and view and picture the supernal beauty and glory beyond. Is it all real? Ah, VIRGINIA, in all this world there is nothing else real and abiding.

No Santa Claus! Thank God! he lives, and he lives forever. A thousand years from now, Virginia, nay, ten times ten thousand years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood.

Authorship[]

Church was not known to be the author until his death in 1906.[13] The editorial is just one of two whose authorship The Sun disclosed;[12] the other being Harold M. Anderson's "[Charles] Lindbergh Flies Alone". Campbell wrote in 2006 that Church would probably not have welcomed The Sun's disclosure, noting that he was generally unwilling to discuss the authorship of editorials.[18]

Later republication[]

"Is There a Santa Claus?" often appears in editorial sections during the Christmas and holiday season.[19] It has become the most reprinted editorial in any newspaper in the English language,[20][21] and has been translated into around 20 languages.[22] Campbell describes it as living on as "enduring inspiration in American journalism."[19] Journalist David W. Dunlap described "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus" as one of the most famous lines in American journalism, placing it after "Headless body in topless bar" and "Dewey Defeats Truman".[23]

The editorial was first reprinted five years later to answer readers' demand for it.[24][b] After 1902, it did not appear in the paper again until 1906, shortly after Church's death. The paper began to re-publish the editorial more regularly after this, including six times in the ensuing ten years and gradually began to "warm to" the editorial, according to the scholar W. Joseph Campbell. Other newspapers began to republish it as well during this period.[26] In 1918 the paper wrote that they got many requests to "reprint again the Santa Claus editorial article" every Christmas season.[16] A book based on the editorial, Is there a Santa Claus?, was published in 1921.[1] The Sun started reprinting the editorial annually at Christmas after 1924, when the paper's editor-in-chief, Frank Munsey, placed as the first editorial on December 23. This practice continued on the 23rd or 24th of the month until the paper's bankruptcy in 1950.[24][26] Elizabeth Press published a children's book in 1972 titled Yes, Virginia that illustrated the editorial and included a brief history of the main characters.[27]

A copy of the letter, hand-written by Virginia and believed by her family to be the original and returned to them by the newspaper[28] was authenticated in 1998 by Kathleen Guzman, an appraiser on the television program Antiques Roadshow.[21] In 2007, the show appraised its value at around $50,000.[28] As of 2015 the letter was held by Virginia's great-granddaughter.[29]

Reception and analysis[]

The historian and journalist Bill Kovarik described the editorial as part of a broader "revival of the Christmas holiday" that took place during the late 19th century in various publications such as Thomas Nast's art.[30] Stephen Nissenbaum wrote that the editorial echoed theology common in the late Victorian era and that its content would have been similar to the content in sermons of the day.[31] In 1997 the journalist Eric Newton, who at the time was working at the Newseum, described the editorial as the sort of "poetry" that newspapers should publish as editorials,[20] while Geo Beach in the Editor & Publisher trade magazine considered Church's writing "brave" and as showing that "love, hope, belief—all have a place on the editorial page".[20] In 2005, W. Joseph Campbell analyzed the editorial, particularly The Sun's reluctance in republishing it, as offering insight into the broader state of American newspapers in the late 19th century.[20]

The journalist Rick Horowitz wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the editorial as providing journalists with an excuse to not write their own essays around Christmas: "they can just slap Francis Church's 'Yes, Virginia,' up there on the page and go straight to the office party."[32] The editorial came under attack in 1951 by members of the Christian Reformed Church in North America in Lynden, Washington, who criticized it for encouraging Virginia to think of her friends as liars.[33]

Adaptations[]

The story of Virginia's inquiry and The Sun's response was adapted in 1932 into an NBC-produced cantata (the only known editorial set to classical music).[34] It has been filmed several times, including as a segment of the short film Santa Claus Story (1945). In 1974 a television special titled Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus, aired on ABC. It was animated by Bill Melendez (who had worked on various Peanuts specials) and won the 1975 Emmy Award for outstanding children special.[35][36] The cartoon was a highly fictionalized account. Charles Bronson, later in 1991, starred in a live action television film based on the same letter. In 1996, the story was adapted into an eponymous holiday musical by David Kirchenbaum (music and lyrics) and Myles McDonnel (book).[34]

A 2009 animated television special titled Yes, Virginia, aired on CBS and featured actors including Neil Patrick Harris and Beatrice Miller.[35] The special was written by the Macy's ad agency as part of their "Believe" Make-A-Wish fundraising campaign. In 2010 a book was written based upon the special. Two years later, Macy's had the special adapted into a musical for students in third through sixth grade. The company gave schools the right to perform the musical for free and gave 100 schools $1,000 grants for performing the musical.[37][38]

In 2003, "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus" was depicted in a mechanical holiday window display at the Lord & Taylor flagship store on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.[39] In December 2015, Macy's Herald Square in New York City, used Virginia's story for their holiday window display, illustrated in three-dimensional figurines and spanning several windows on the south side of the store along 34th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues. This version of "Yes, Virginia" is based on the 2009 television special.[40]

"Yes, Virginia, there is (a)..." has become an idiomatic expression to insist that something is true.[41]

Virginia O'Hanlon[]

Laura Virginia O'Hanlon[42] was born on July 20, 1889, in New York City, New York. Her marriage to Edward Douglas in the 1910s was brief, and ended with him deserting her shortly before their daughter, Laura, was born. She was listed as divorced in the 1930 United States Census but nevertheless kept her ex-husband's surname the rest of her life (as was common practice), styled as "Laura Virginia O'Hanlon Douglas."[20]

Douglas received her Bachelor of Arts from Hunter College in 1910, a master's degree in education from Columbia University in 1912, and a doctorate from Fordham University in the 1930s.[28] The title of her dissertation was "The Importance of Play".[43] She was a school teacher in the New York City Independent School District. She started her career as an educator in 1912, became a junior principal in 1935, and retired in 1959.[44]

Douglas received a steady stream of mail about her letter throughout her life. She would include a copy of the editorial in her replies.[45] In an interview later in life, she credited it with shaping the direction of her life quite positively.[46][28] Douglas died on May 13, 1971, at the age of 81, in a nursing home in Valatie, New York.[47] She is buried at the Chatham Rural Cemetery in North Chatham, New York.[48] In 2009 the Virginia O'Hanlon Scholarship Fund was established at the private school which occupies O'Hanlon's childhood home.[49][50] The school also added a commemorative plaque on the building about the letter.[50]

See also[]

- Paternalistic deception

- Santa Claus: Controversy about deceiving children

Notes[]

- ^ Andy Rooney doubted that a young girl would refer to children her own age as "my little friends" and theorized that Virginia's father assisted her in composing the letter or even wrote it himself.[8]

- ^ While some sources state that the editorial was republished every year after 1897, it did not appear until December 1902, with the comment that "[S]ince its original publication, the Sun has refrained from reprinting the article on Santa Claus which appeared several years ago, but this year requests for its reproduction have been so numerous that we yield."[25]

References[]

- ^ a b c Frasca, Ralph (1989). "William Conant Church (11 August 1836–23 May 1917) and Francis Pharcellus Church (22 February 1839–11 April 1906)". Dictionary of Literary Biography.

- ^ Gilbert, Kevin (2015). "Famous New Yorker: Francis Pharcellus Church" (PDF). New York News Publisher's Association. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Francis P. Church". The New York Times. April 13, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Campbell 2006, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 132.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (December 25, 2014). "Virginia of 'Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus' grew up to be a teacher". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Rooney 2007.

- ^ Campbell 2006, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Turner 1999, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Forbes 2007, p. 90.

- ^ a b Ranniello, Bruno (December 25, 1969). "'Yes, Virginia' Editorialist: Francis Pharcellus Church". The Bangor Daily News. p. 22. Retrieved December 20, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Sebakijje, Lena. "Research Guides: Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus: Topics in Chronicling America: Introduction". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 134.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, p. 128.

- ^ ""Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus"". Newseum. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Campbell 2006, p. 129.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, p. 196.

- ^ a b c d e Campbell, W. Joseph (Spring 2005). "The grudging emergence of American journalism's classic editorial: New details about 'Is There A Santa Claus?'". American Journalism Review. University of Maryland, College Park: Philip Merrill College of Journalism. 22 (2): 41–61. doi:10.1080/08821127.2005.10677639. S2CID 146945285. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ^ a b "1897 'Yes, Virginia' Santa Claus Letter". Antiques Roadshow. Public Broadcasting Service. July 19, 1997. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (September 21, 1997). "Yes, Virginia, a Thousand Times Yes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (December 25, 2015). "1933 | P.S., Virginia, There's a New York Times, Too". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Applebome, Peter (December 13, 2006). "Tell Virginia the Skeptics Are Still Wrong". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Campbell 2006, p. 130.

- ^ a b Campbell 2006, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Long, Sidney (December 3, 1972). "... And a Partridge in a Pear Tree". The New York Times. p. BR8. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 119470293.

- ^ a b c d Gollom, Mark (December 22, 2019). "Yes, Virginia, your Christmas legacy lives on". CBC News. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "Yes, there is a Santa Claus". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ Kovarik 2015, pp. 73.

- ^ Nissenbaum 1997, p. 88.

- ^ Campbell 2006, pp. 196–197.

- ^ "Santa Survives Protest; Objection of Church Group to His Appearance Is Rejected". The New York Times. December 23, 1951. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Bowler 2000, pp. 252–253.

- ^ a b Crump 2019, p. 349.

- ^ Woolery 1989, p. 464.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (December 25, 2014). "Macy's gives its Santa musical to public schools for free — and gets tons of priceless publicity". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (August 22, 2012). "Giving Little Virginia Something to Sing About". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ "Christmas in New York: Lord and Taylor Christmas Holiday Window displays 2003 Photo Gallery". Gonyc.about.com. November 2, 2009. Archived from the original on February 25, 2006. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ "Yes Virginia, there really is a Macy's". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ ""Yes, Virginia…", by Joanne, 20 Dec 2010". About English Idioms. December 10, 2010. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (December 24, 2010). "To Virginia's Family, Santa Claus Is Still Real". The New York Times. pp. A23, A29. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ^ Douglas, Laura V. (January 1, 1930). The Importance of Play (Thesis). Fordham University. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Virginia, Now 70, Quits As Teacher; School Principal Who at 8 Asked 'Is There a Santa?' Is a Guest at Dinner" (Abstract of subscription PDF). The New York Times. June 12, 1959. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

Mrs. Laura Virginia Douglas, retiring after forty-three years as a public school teacher and principal, was given a farewell dinner by her colleagues last night at the Towers Hotel in Brooklyn.

- ^ Morrison, Jim "Santa Junior"; McElhany, Jennifer. "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus". National Christmas Centre, Exhibits. National Christmas Centre. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

Throughout her life she received a steady stream of mail about the letter, and to each reply she attached an attractive printed copy of the editorial.

- ^ "Yes Virginia — 66 years later". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. December 24, 1963. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ "Virginia O'Hanlon, Santa's Friend, Dies; Virginia O'Hanlon Dead at 81". The New York Times. May 14, 1971. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

Valatie, N. Y., May 13 – Virginia O'Hanlon Douglas, who as a child was reassured that "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus", died today at the age of 81.

- ^ Maurer, David A. (December 24, 2016). "Yesteryears: Yes, Virginia, Part 2: A life shaped by a joyful, fearless belief". The Daily Progress. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Haberman, Clyde (December 24, 2004). "NYC - Yes, New York, There Was A Virginia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Elliott, Stuart (December 7, 2009). "Yes, Virginia, There Is a Scholarship". Media Decoder Blog. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Bowler, Gerry, ed. (2000). "Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus.'". The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Limited. pp. 252–253. ISBN 9780771015311.

- Campbell, W. Joseph (2006). The Year That Defined American Journalism. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203700495. ISBN 978-1-135-20505-8.

- Crump, William D. (2019). Happy Holidays—Animated! A Worldwide Encyclopedia of Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and New Year's Cartoons on Television and Film. McFarland & Co. p. 349. ISBN 9781476672939.

- Forbes, Bruce David (October 10, 2007). Christmas A Candid History. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520933729. ISBN 978-0-520-93372-9.

- Kovarik, Bill (2015). Revolutions in Communication: Media History from Gutenberg to the Digital Age. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-62892-479-4.

- Nissenbaum, Stephen (1997). The battle for Christmas. New York: Vintage Books. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-679-74038-4.

- Rooney, Andy (2007). Common Nonsense. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781586486174.

- Turner, Hy B. (1999). When giants ruled : the story of Park Row, New York's great newspaper street. New York: Fordham University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-0-8232-1943-8.

- Woolery, George W. (1989). Animated TV Specials: The Complete Directory to the First Twenty-Five Years, 1962-1987. Scarecrow Press. pp. 463–464. ISBN 0-8108-2198-2. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

External links[]

The full text of "Is There a Santa Claus?" (New York Sun) at Wikisource

The full text of "Is There a Santa Claus?" (New York Sun) at Wikisource Media related to Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus at Wikimedia Commons- Full text of the editorial with digital image from the original newspaper. From the Newseum, Washington, DC

- WTEN – Albany PBS – Virginia O'Hanlon reading the editorial to children in the 1960s on YouTube

- WNYC New York December 1937 radio interview with Virginia O'Hanlon Douglas

- 1897 in the United States

- 1897 documents

- Christmas television specials

- Quotations from literature

- Santa Claus

- Santa Claus in fiction

- Christmas essays

- 1890s neologisms

- Christmas in New York (state)