Welding defect

A welding defect is any flaw that compromises the usefulness of a weldment. There is a great variety of welding defects. Welding imperfections are classified according to ISO 6520[1] while their acceptable limits are specified in ISO 5817 [2] and ISO 10042.[3]

Major causes[]

According to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), causes of welding defects can be broken down as follows: 41% poor process conditions, 32% operator error, 12% wrong technique, 10% incorrect consumables and 5% bad weld grooves.[4]

Hydrogen embrittlement[]

Residual stresses[]

The magnitude of stress that can be formed from welding can be roughly calculated using:[5]

Where E is Young's modulus, α is the coefficient of thermal expansion, and ΔT is the temperature change. For steel this calculates out to be approximately 3.5 GPa (510,000 psi).

Types[]

Cracks[]

Defects related to fracture.

Arc strikes[]

An Arc Strike is a discontinuity resulting from an arc, consisting of any localized remelted metal, heat affected metal, or change in the surface profile of any metal object. [6] Arc Strikes result in localized base metal heating and very rapid cooling. When located outside the intended weld area, they may result on hardening or localized cracking, and may serve as potential sites for initiating fracture. In Statically Loaded Structures, arc strikes need not be removed, unless such removal is required in contract documents. However, in Cyclically Loaded Structures, arc strikes may result in stress concentrations that would be detrimental to the serviceability of such structures and should be ground smooth and visually inspected for cracks. [7]

Cold cracking[]

Residual stresses can reduce the strength of the base material, and can lead to catastrophic failure through cold cracking. Cold cracking is limited to steels and is associated with the formation of martensite as the weld cools. The cracking occurs in the heat-affected zone of the base material. To reduce the amount of distortion and residual stresses, the amount of heat input should be limited, and the welding sequence used should not be from one end directly to the other, but rather in segments.[8]

Cold cracking only occurs when all the following preconditions are met:[9]

- susceptible microstructure (e.g. martensite)

- hydrogen present in the microstructure (hydrogen embrittlement)

- service temperature environment (normal atmospheric pressure): -100 to +100 °F

- high restraint

Eliminating any one of these will eliminate this condition.

Crater crack[]

Crater cracks occur when a welding arc is broken, a crater will form if adequate molten metal is available to fill the arc cavity.[10]

Hat crack[]

Hat cracks get their name from the shape of the cross-section of the weld, because the weld flares out at the face of the weld. The crack starts at the fusion line and extends up through the weld. They are usually caused by too much voltage or not enough speed.[10]

Hot cracking[]

Hot cracking, also known as solidification cracking, can occur with all metals, and happens in the fusion zone of a weld. To diminish the probability of this type of cracking, excess material restraint should be avoided, and a proper filler material should be utilized.[8] Other causes include too high welding current, poor joint design that does not diffuse heat, impurities (such as sulfur and phosphorus), preheating, speed is too fast, and long arcs.[11]

Underbead crack[]

An underbead crack, also known as a heat-affected zone (HAZ) crack,[12] is a crack that forms a short distance away from the fusion line; it occurs in low alloy and high alloy steel. The exact causes of this type of crack are not completely understood, but it is known that dissolved hydrogen must be present. The other factor that affects this type of crack is internal stresses resulting from: unequal contraction between the base metal and the weld metal, restraint of the base metal, stresses from the formation of martensite, and stresses from the precipitation of hydrogen out of the metal.[13]

Longitudinal crack[]

Longitudinal cracks run along the length of a weld bead. There are three types: check cracks, root cracks, and full centerline cracks. Check cracks are visible from the surface and extend partially into the weld. They are usually caused by high shrinkage stresses, especially on final passes, or by a hot cracking mechanism. Root cracks start at the root and extent part way into the weld. They are the most common type of longitudinal crack because of the small size of the first weld bead. If this type of crack is not addressed then it will usually propagate into subsequent weld passes, which is how full cracks (a crack from the root to the surface) usually form.[10]

Reheat cracking[]

Reheat cracking is a type of cracking that occurs in HSLA steels, particularly chromium, molybdenum and vanadium steels, during postheating. The phenomenon has also been observed in austenitic stainless steels. It is caused by the poor creep ductility of the heat affected zone. Any existing defects or notches aggravate crack formation. Things that help prevent reheat cracking include heat treating first with a low temperature soak and then with a rapid heating to high temperatures, grinding or peening the weld toes, and using a two layer welding technique to refine the HAZ grain structure.[14][15]

Root and toe cracks[]

A root crack is the crack formed by the short bead at the root(of edge preparation) beginning of the welding, low current at the beginning and due to improper filler material used for welding. The major reason for these types of cracks is hydrogen embrittlement. These types of defects can be eliminated using high current at the starting and proper filler material. Toe crack occurs due to moisture content present in the welded area, it is a part of the surface crack so can be easily detected. Preheating and proper joint formation is a must for eliminating these types of defects.

Transverse crack[]

Transverse cracks are perpendicular to the direction of the weld. These are generally the result of longitudinal shrinkage stresses acting on weld metal of low ductility. Crater cracks occur in the crater when the welding arc is terminated prematurely. Crater cracks are normally shallow, hot cracks usually forming single or star cracks. These cracks usually start at a crater pipe and extend longitudinal in the crater. However, they may propagate into longitudinal weld cracks in the rest of the weld.

Distortion[]

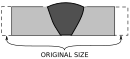

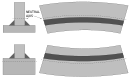

Welding methods that involve the melting of metal at the site of the joint necessarily are prone to shrinkage as the heated metal cools. Shrinkage then introduces residual stresses and distortion. Distortion can pose a major problem, since the final product is not the desired shape. To alleviate certain types of distortion the workpieces can be offset so that after welding the product is the correct shape.[16] The following pictures describe various types of welding distortion:[17]

Transverse shrinkage

Angular distortion

Longitudinal shrinkage

Fillet distortion

Neutral axis distortion

Gas inclusion[]

Gas inclusions is a wide variety of defects that includes porosity, blow holes, and pipes (or wormholes). The underlying cause for gas inclusions is the entrapment of gas within the solidified weld. Gas formation can be from any of the following causes- high sulphur content in the workpiece or electrode, excessive moisture from the electrode or workpiece, too short of an arc, or wrong welding current or polarity.[12]

Inclusions[]

There are two types of inclusions: linear inclusions and rounded inclusions. Inclusions can be either isolated or cumulative. Linear inclusions occur when there is slag or flux in the weld. Slag forms from the use of a flux, which is why this type of defect usually occurs in welding processes that use flux, such as shielded metal arc welding, flux-cored arc welding, and submerged arc welding, but it can also occur in gas metal arc welding. This defect usually occurs in welds that require multiple passes and there is poor overlap between the welds. The poor overlap does not allow the slag from the previous weld to melt out and rise to the top of the new weld bead. It can also occur if the previous weld left an undercut or an uneven surface profile. To prevent slag inclusions the slag should be cleaned from the weld bead between passes via grinding, wire brushing, or chipping.[18]

Isolated inclusions occur when rust or mill scale is present on the base metal.[19]

Lack of fusion and incomplete penetration[]

Lack of fusion is the poor adhesion of the weld bead to the base metal; incomplete penetration is a weld bead that does not start at the root of the weld groove. Incomplete penetration forms channels and crevices in the root of the weld which can cause serious issues in pipes because corrosive substances can settle in these areas. These types of defects occur when the welding procedures are not adhered to; possible causes include the current setting, arc length, electrode angle, and electrode manipulation.[20] Defects can be varied and classified as critical or non critical. Porosity (bubbles) in the weld are usually acceptable to a certain degree. Slag inclusions, undercut, and cracks are usually unacceptable. Some porosity, cracks, and slag inclusions are visible and may not need further inspection to require their removal. Small defects such as these can be verified by Liquid Penetrant Testing (Dye check). Slag inclusions and cracks just below the surface can be discovered by Magnetic Particle Inspection. Deeper defects can be detected using the Radiographic (X-rays) and/or Ultrasound (sound waves) testing techniques.

Lamellar tearing[]

Lamellar tearing is a type of welding defect that occurs in rolled steel plates that have been welded together due to shrinkage forces perpendicular to the faces of the plates.[21] Since the 1970s, changes in manufacturing practices limiting the amount of sulfur used have greatly reduced the incidence of this problem.[22]

Lamellar tearing is caused mainly by sulfurous inclusions in the material. Other causes include an excess of hydrogen in the alloy. This defect can be mitigated by keeping the amount of sulfur in the steel alloy below 0.005%.[22] Adding rare earth elements, zirconium, or calcium to the alloy to control the configuration of sulfur inclusions throughout the metal lattice can also mitigate the problem.[23]

Modifying the construction process to use cast or forged parts in place of welded parts can eliminate this problem, as Lamellar tearing only occurs in welded parts.[21]

Undercut[]

Undercutting is when the weld reduces the cross-sectional thickness of the base metal and which reduces the strength of the weld and workpieces. One reason for this type of defect is excessive current, causing the edges of the joint to melt and drain into the weld; this leaves a drain-like impression along the length of the weld. Another reason is if a poor technique is used that does not deposit enough filler metal along the edges of the weld. A third reason is using an incorrect filler metal, because it will create greater temperature gradients between the center of the weld and the edges. Other causes include too small of an electrode angle, a dampened electrode, excessive arc length, and slow speed.[24]

References[]

- ^ BS EN ISO 6520-1: "Welding and allied processes — Classification of geometric imperfections in metallic materials — Part 1: Fusion welding"(2007)

- ^ BS EN ISO 5817: "Welding — Fusion-welded joints in steel, nickel, titanium and their alloys (beam welding excluded) — Quality levels for imperfections" (2007)

- ^ BS EN ISO 10042: "Welding. Arc-welded joints in aluminium and its alloys. Quality levels for imperfections" (2005)

- ^ Matthews, Clifford (2001), ASME engineer's data book, ASME Press, p. 211, ISBN 978-0-7918-0155-0.

- ^ Bull, Steve (2000-03-16), Magnitude of stresses generated, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, archived from the original on 2009-12-06, retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ AWS A3.0: 2020 - Standard Welding Terms and Definitions

- ^ aisc.org/steel-solutions-center/engineering-faqs/8.5.-repairs

- ^ a b Cary & Helzer 2005, pp. 404–405.

- ^ [1] A Brief MIG welder Troubleshooting Guide

- ^ a b c Raj, Jayakumar & Thavasimuthu 2002, p. 128.

- ^ Bull, Steve (2000-03-16), Factors promoting hot cracking, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, archived from the original on 2009-12-06, retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ a b Raj, Jayakumar & Thavasimuthu 2002, p. 126.

- ^ Rampaul 2003, p. 208.

- ^ Bull, Steve (2000-03-16), Reheat cracking, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, archived from the original on 2009-12-07, retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Bull, Steve (2000-03-16), Reheat cracking, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, archived from the original on 2009-12-07, retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Weman 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Bull, Steve (2000-03-16), Welding Faults and Defects, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, archived from the original on 2009-12-06, retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Defects/imperfections in welds - slag inclusions, archived from the original on 2009-12-06, retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ^ Bull, Steve (2000-03-16), Welding Faults and Defects, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, archived from the original on 2009-12-05.

- ^ Rampaul 2003, p. 216.

- ^ a b Bull, Steve (2000-03-16), Welding Faults and Defects, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, archived from the original on 2009-12-04.

- ^ a b Still, J. R., Understanding Hydrogen Failures, retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Ginzburg, Vladimir B.; Ballas, Robert (2000), Flat rolling fundamentals, CRC Press, p. 142, ISBN 978-0-8247-8894-0.

- ^ Rampaul 2003, pp. 211–212.

Bibliography[]

- Cary, Howard B.; Helzer, Scott C. (2005), Modern Welding Technology, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, ISBN 0-13-113029-3.

- Raj, Baldev; Jayakumar, T.; Thavasimuthu, M. (2002), Practical non-destructive testing (2nd ed.), Woodhead Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85573-600-9.

- Rampaul, Hoobasar (2003), Pipe welding procedures (2nd ed.), Industrial Press, ISBN 978-0-8311-3141-8.

- Moreno, Preto (2013), Welding Defects (1st ed.), Aracne, ISBN 978-88-548-5854-1.

- Weman, Klas (2003), Welding processes handbook, New York, NY: CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-1773-8.

External links[]

- Welding