World altitude record (mountaineering)

In the history of mountaineering, the world altitude record referred to the highest point on the Earth's surface which had been reached, regardless of whether that point was an actual summit. The world summit record referred to the highest mountain to have been successfully climbed. The terms are most commonly used in relation to the history of mountaineering in the Himalaya and Karakoram ranges, though modern evidence suggests that it was not until the 20th century that mountaineers in the Himalaya exceeded the heights which had been reached in the Andes. The altitude and summit records rose steadily during the early 20th century until 1953, when the ascent of Mount Everest made the concept obsolete.

19th century and before[]

European exploration of the Himalaya began in earnest during the mid-19th century, and the earliest people known to have climbed in the range were surveyors of the Great Trigonometric Survey (GTS). During the 1850s and 1860s they climbed dozens of peaks of over 6,100 m (20,000 ft) and several of over 6,400 m (21,000 ft) in order to make observations, and it was during this period that claims to have ascended the highest point yet reached by man began to be made.[1]

Most of these early claims have now been rendered invalid by the discovery of the bodies of three children at the 6,739 m (22,110 ft) summit of Llullaillaco in South America: Inca sacrifices dated to around AD 1500.[2] There is no direct evidence that the Incas reached higher points, but the discovery of the skeleton of a guanaco on the summit ridge of Aconcagua (6,962 m, 22,841 ft) suggests that they also climbed on that mountain, and the possibility of Pre-Columbian ascents of South America's highest peak cannot be ruled out.[3]

In the Himalaya yaks have been reported at heights of up to 6,100 m (20,000 ft) and the summer snow line can be as high as 6,500 m (21,300 ft). It is likely that local inhabitants went to such heights in search of game, and possibly higher while exploring trade routes, but they did not live there, and there is no evidence that they attempted to climb the summits of the Himalaya before the arrival of Europeans.[4]

In August 1855, the Bavarian brothers Adolf and Robert Schlagintweit of the Magnetic Survey of India made an attempt to climb Kamet (7,756 m), in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand, India, near the Tibetan border. Spending 10 days above 17,000 ft (5,200 m) they approached the mountain from the Tibetan side, climbing the northwest ridge of the subsidiary peak Abi Gamin. From their highest camp at 19,325 ft (5,890 m), they and some of their guides and carriers reached an altitude of 22,259 ft (6,785 m) according to their barometric measurements, which would have put them higher than Llullaillaco. [5][6]

Many early claims of world altitude records are muddied by incomplete surveying and lack of knowledge of local geography, which have led to reassessments of many of the heights which were originally claimed. In 1862 a khalasi (an Indian assistant of the GTS) climbed Shilla, a summit in Himachal Pradesh which was claimed to be over 7,000 m (23,000 ft) high. More recent surveys have, however, fixed its height at 6,111 m (20,049 ft).[7] Three years later William Johnson of the GTS claimed to have climbed a 7,284 m (23,898 ft) peak during an illicit journey into China, but the mountain he climbed has since been measured at 6,710 m (22,014 ft).[7]

Above 7,000 m[]

The first pure mountaineers (as opposed to surveyors) to have climbed in the Himalaya were the English barrister William Graham, the Swiss hotelier Emil Boss and the Swiss mountain guide Ulrich Kaufmann, who together climbed extensively in the area in 1883. The previous year Graham had made the first ascent of the Dent du Géant, and Boss and Kaufmann had equally notably very nearly made the first ascent of Aoraki / Mount Cook in New Zealand. Among others, they claimed a near ascent of Dunagiri (reaching about 6,900 m), an ascent of Changabang (6,864 m, 22,520 ft) in July in the Garhwal Himalaya, and an ascent to 30 feet below the east summit of Kabru 7,338 metres (24,075 ft) south of Kangchenjunga in October, but most of the ascents are disputed. It is not claimed that they lied about their ascents, rather that the poor quality of maps at the time may have led them to be unsure of which mountain they were actually on, and to make estimates of their height which owed more to wishful thinking than scientific measurements.[8] Their description of Changabang is so at variance with the mountain itself that their claim was doubted almost immediately, and by 1955 was not taken seriously anymore.[9]

The team's ascent over the east face of Kabru is less readily dismissed. Although their report of views of Mount Everest from the top appears convincing, Graham's description of the ascent was also vague, and this, coupled with the speed of their claimed ascent and his failure to report significant effects of altitude sickness, have led many to assume that here they also climbed a lower peak in the same area.[8][10] Their claim was, however, supported in the following years by climbers such as Douglas Freshfield, Norman Collie, Edmund Garwood, Carl Rubenson, and Tom Longstaff, and more recently Walt Unsworth has argued that as a man who was more interested in climbing than in making observations, the vagueness of his description is to be expected, and that now Everest has been climbed in a single day without oxygen, his claims sound less outlandish than they once did.[11] In 2009, Willy Blaser and Glyn Hughes wrote a spirited defense of the ascent in the Alpine Journal, arguing that Graham and Boss's criticism of the maps of the Garhwal Himalaya had led to bad blood.[12] If Graham, Boss and Kaufmann did climb Kabru it was a remarkable achievement for its time, establishing an altitude record which was not broken for twenty-six years.[13]

Nine years later, another claim to the world altitude record was made by Martin Conway in the course of his expedition to the Karakoram in 1892. Together with Matthias Zurbriggen and Charles Granville Bruce, Conway made an attempt on Baltoro Kangri and on 25 August reached a subsidiary summit which he named Pioneer Peak. The barometer showed a height of 22,600 ft (6,900 m) which Conway optimistically rounded up to 23,000 ft (over 7,000 m). However, Pioneer Peak has since been measured at only 6,501 metres (21,329 ft).[14]

On 14 January 1897, Matthias Zurbriggen went on to make the first recorded ascent of Aconcagua in the Andes. Aconcagua is 6,962 metres (22,841 ft) high and, if the claims of Boss and Graham are discounted, was still the highest point to have been reached at that time.[15]

It was several more years before the 7,000 m barrier would be broken with reasonable certainty. In July 1905 Tom George Longstaff, accompanied by the alpine guides Alexis and Henri Brocherel from Courmayeur and six local porters, made an attempt on Gurla Mandhata.[16] The height they reached is estimated at between 7,000 m (23,000 ft)[17] and 7,300 m (24,000 ft),[18] greater than the height of Aconcagua.

In 1907 Longstaff and the Brocherel brothers returned to the Himalayas and led an expedition with the aim of climbing Nanda Devi, but unable to penetrate its "sanctuary" of surrounding peaks turned their attention to Trisul, which they climbed on June 12.[15] At 7,120 metres (23,360 ft) Trisul became the highest summit to have been climbed whose height was accurately known and whose ascent was undisputed.[19]

This altitude record, though not the summit record, was broken a few months later, on 20 October 1907, when the Norwegians Carl Wilhelm Rubenson and Ingvald Monrad Aas came within 50 m of ascending the 7338 m east summit of Kabru. It is noteworthy that Carl Rubenson afterwards believed that Graham, Boss and Kaufmann had ascended that summit 24 years before.[12]

An undisputed new altitude record was achieved in 1909 by the Duke of the Abruzzi's expedition to the Karakoram. After failing to make progress on K2 the Duke led an attempt on Chogolisa, where they reached a height of approximately 7,500 m (24,600 ft) before turning around just 150 m below the summit due to bad weather and the risk of falling through a cornice in poor visibility.[20]

The undisputed summit record, though not the altitude record, was broken by 8 meters on June 14, 1911, when the Scottish chemist, explorer, and mountaineer Alec Kellas together with the Sherpas "Sony" and "Tuny's brother" climbed the 7,128 metres (23,386 ft) high Pauhunri on the border of Sikkim and Tibet. Until the late 20th century this mountain was thought to be only 7,065 metres (23,179 ft), so this record was not realized at the time.[21]

British Everest expeditions[]

The world altitude record was not broken again until the British expeditions to Mount Everest, and would then become the exclusive preserve of climbers on the world's highest mountain. On the 1922 expedition the record was broken twice. On 20 May, George Mallory, Howard Somervell and Edward Norton reached 8,170 m (26,800 ft) on the mountain's North Ridge, without using supplemental oxygen.[22] Three days later George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce, using supplemental oxygen, followed the same route and went even higher—turning around at about 8,320 m (27,300 ft) when Bruce's oxygen apparatus failed.[23]

In 1924 the British made another attempt on Everest, and the world altitude record was again broken. On 4 June, Edward Norton, without supplemental oxygen, reached a point on the mountain's Great Couloir 8,570 m (28,120 ft) high, his companion Howard Somervell having turned around a short distance before.[24] This was an altitude record which would not be broken, with certainty, until the 1950s, or without supplemental oxygen until 1978. Three days later George Mallory and Andrew Irvine disappeared while making their own attempt on the summit. There has been much debate over whether they reached a greater height than Norton, or even the summit, but as there is no direct proof they are not generally credited with a record.

The British made several further expeditions to Mount Everest in the 1930s. Twice in 1933 climbing parties reached approximately the same point as Norton; first Lawrence Wager and Percy Wyn-Harris, and later Frank Smythe, but there was no advance on Norton's record.[25]

Inter-war years[]

While there would be no advance on the altitude record until the 1950s, the summit record was broken five times in the inter-war years.

The first was by just another 6 meters, when on 15 September 1928 the German mountaineers Karl Wien and and the Austrian mountaineer and cartographer reached the summit of the 7,134 m (23,406 ft) Kaufman Peak in the Pamirs, a mountain up to that year thought to be the highest mountain in the Soviet Union. After the expedition, it was renamed Lenin Peak.

The next advance was a by-product of the international expedition to Kanchenjunga led by Günter Dyhrenfurth in 1930. The attempt on Kanchenjunga itself was abandoned after an avalanche had killed Chettan Sherpa, but members of the team stayed to climb a number of smaller peaks in the area. , who had barely escaped the avalanche, broke his own summit record twice in two weeks: on 24 May he solo-climbed 7,177 m (23,547 ft) Nepal Peak near Kirat Chuli, and on 3 June and he climbed 7,462 m (24,482 ft) Jongsong Peak, planting a Swabian and Tyrolean flag on top.[15][26][27]

In 1931 the summit record was broken again with the ascent of Kamet. Frank Smythe, Eric Shipton, R.L. Holdsworth and reached the summit on 21 June. At 7,756 m (25,446 ft), Kamet was the first mountain over 7,500 m and 25,000 ft to be climbed.[28]

The summit record was raised once more before the Second World War brought an effective halt to mountaineering in the Himalaya. Nanda Devi, at 7,816 m (25,643 ft) the highest mountain wholly within the British Empire, had been the object of several expeditions, and it was finally climbed on 29 August 1936 by Bill Tilman and Noel Odell.[29]

1950s and ascent of Everest[]

After the Second World War, the formerly closed and secretive kingdom of Nepal, wary of the intentions of the People's Republic of China and seeking friends in the West, began to open its borders. For the first time its peaks, including the south side of Everest, became accessible to Western mountaineers, triggering a new wave of exploration.[30] There was one further improvement on the summit record before Everest was conquered. On 3 June 1950 Annapurna (8,091 m, 26,545 ft) became the first 8,000 m mountain to be climbed when the French climbers Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal reached its summit on the 1950 French Annapurna expedition. Both Herzog and Lachenal lost their toes to frostbite; Herzog also lost most of his fingers.[31]

The first attempt to climb Everest from the south was made by a Swiss team in 1952. The expedition's high point was reached by Raymond Lambert and the team's Nepali Indian sardar Tenzing Norgay on 26 May, when they reached a point approximately 200 m (650 ft) below the South Summit before turning around in the knowledge that they would not reach the summit in daylight. Their estimated height of 8,600 m (28,210 ft) was slightly higher than the previous altitude record set by the British on the north side of the mountain.[32] The Swiss made further attempts later in May, and again in autumn after the monsoon, but did not regain Lambert and Tenzing's high point.

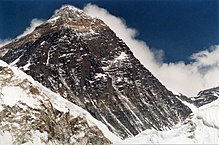

Mount Everest was climbed the following year. On 26 May, three days before the successful attempt, Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans reached the South Summit before turning back due to malfunctioning oxygen apparatus. Their height of 8,760 m (28,750 ft) represented a new, short lived, altitude record, and can be seen as a summit record if this is taken to include minor tops as well as genuine mountains.[33] Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay finally reached the 8,848 m (29,029 ft) true summit on 29 May 1953, marking the final chapter in the history of the mountaineering altitude record.[34] While the exact height of Everest's summit is subject to minor variation due to the level of snow cover and the gradual upthrust of the Himalaya, significant changes to the world altitude record are now impossible.

Women's altitude record[]

Female mountaineers were rare in the early 20th century,[35] and the maximum height attained by a woman lagged behind that claimed by male climbers. The first woman to climb extensively in the Karakoram was Fanny Bullock Workman, who made a number of ascents, including that of Pinnacle Peak, a 6,930 m (22,740 ft) subsidiary summit of Nun Kun, in 1906.[17] Her claim on the women's altitude record was challenged by Annie Smith Peck in 1908 after she made an ascent of the north peak of Huascarán, which she claimed was higher than Pinnacle Peak. The ensuing controversy was bitter and public, and eventually resolved in Bullock Workman's favour when she hired a team of surveyors to measure the height of Huascarán. The north peak was found to be 6,648 m (21,811 ft) tall - some 600 m lower than Smith Peck's estimate.[36]

In 1934 Hettie Dyhrenfurth, wife of Günter Dyhrenfurth, became the first woman to exceed 7000 m when she climbed Sia Kangri (7,422 m (24,350 ft)). Her summit record would stand for 25 years, though her altitude record was broken by the French climber Claude Kogan, who reached approximately 7,600 m (24,900 ft) on Cho Oyu in 1954.[37] The following year saw the first all-female team to visit the Himalayas, made up of Monica Jackson, Evelyn McNicol and Elizabeth "Betty" Stark, making the first ascent of , 6,151 m (20,180 ft).[38]

In 1959, Phantog of the Chinese female mountaineering team reached the summit of Muztagh Ata at 7,509 m (24,636 ft).[39][40] Phantog later went on to become the second woman to summit Mount Everest 11 days after Junko Tabei.

The first female ascent of an 8000 m peak came in 1974, when three Japanese women, , Mieko Mori and climbed Manaslu, at 8,163 m (26,781 ft).[37] A year later Junko Tabei of Japan made the first female ascent of Mount Everest on 16 May 1975.[37]

The highest mountain to have had a female first ascent is Gasherbrum III, 7,946 m (26,070 ft), which was first climbed by Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz and Wanda Rutkiewicz (along with two male climbers) in August 1975.[41]

See also[]

- List of past presumed highest mountains

- Highest unclimbed mountain

- List of Andean peaks with known pre-Columbian ascents

References[]

- ^ Sale, Richard; Cleare, John (2000). Climbing the World's 14 Highest Mountains: The History of the 8,000-Meter Peaks. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-89886-727-5.

- ^ Sale and Cleare, p.21

- ^ Secor, R. J.; Hopkins, Ralph Lee; Kukathas, Uma; Thomas, Crystal (1999). Aconcagua: A Climbing Guide. The Mountaineers Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-89886-669-8.

- ^ Sale and Cleare, pp. 21-22

- ^ Frank Smythe, Kamet Conquered: The historic first ascent of a Himalayan giant, p. 15

- ^ Moritz von Brescius, Friederike Kaiser, Stephanie Kleidt Böhlau, Über den Himalaya: Die Expedition der Brüder Schlagintweit nach Indien und Zentralasien 1854 bis 1858, Verlag Köln Weimar, 2015, pp. 25-26

- ^ a b Sale and Cleare, p. 22

- ^ a b Sale and Cleare, p. 23

- ^ Mason, Kenneth (1955). Abode of the Snow. Rupert Hart-Davis. p. 93. Reprinted 1987 by Diadem Books, ISBN 978-0-906371-91-6

- ^ Mason, pp 94-95

- ^ Unsworth, Walt (1994). Hold the Heights: The Foundations of Mountaineering. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. pp. 234–236.

- ^ a b Willy Blaser and Glyn Hughes, Kabru 1883, a reassessment, The Alpine Journal 2009, p. 209

- ^ Unsworth (1994) p. 235

- ^ Curran, Jim (1995). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-340-66007-2.

- ^ a b c Sale and Cleare, p. 24

- ^ T.G. Longstaff, An attempt to climb Gurla Mandhata, Chapter 8 in Western Tibet and the British borderland, Edward Arnold Publisher, London 1906.

- ^ a b Neate, Jill (1990). High Asia: An Illustrated History of the 7,000 Metre Peaks. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-238-6.

- ^ Mason, p. 115

- ^ Mason, p. 117

- ^ Curran p. 70

- ^ "Scottish climber revealed to be altitude record-breaker – 80 years on" CaledonianMercury.com. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ Unsworth, Walt (2000). Everest - The Mountaineering History (3rd ed.). Bâton Wicks. pp. 84–90. ISBN 978-1-898573-40-1.

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 91-95

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 120-122

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 158-184

- ^ Frank Smythe, The Kangchenjunga Adventure: The 1930 Expedition to the Third Highest Mountain in the World, Vertebrate Publishing, 2013

- ^ Bettina Hoerlin, Steps of Courage: My Parents' Journey from Nazi Germany to America, pp. 24-26

- ^ Sale and Cleare, pp. 24-25

- ^ Sale and Cleare, p. 25

- ^ Sale and Cleare, p. 28

- ^ Sale and Cleare, pp. 31-36

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 289-290

- ^ Unsworth (2000), p. 329

- ^ Unsworth (2000), pp. 334-337

- ^ Jordan, Jennifer (2006). Savage Summit: the life and death of the first women who climbed K2. New York: Harper. pp. 5–8. ISBN 0-06-058716-4.

- ^ Jordan, pp. 6-7

- ^ a b c Jordan, p. 7

- ^ Elizabeth Stark, Jugal Himal, The Himalayan Journal 19 (1956). The height is for Gyalsten Peak on the Finn Topographic Map of Nepal 2885-16, which corresponds exactly with the description and picture in the article by Stark

- ^ Alison Osius, [1]

- ^ "Pan Duo: China's first woman on top of world – CCTV-International". September 27, 2009. Archived from the original on July 11, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ Jordan, p. 32-33

- History of mountaineering

- Sports world records

- Record progressions

- Highest things