Zmiiv

Zmiiv

Зміїв Змиёв | |

|---|---|

Downtown Zmijiv | |

Coat of arms | |

Zmiiv | |

| Coordinates: 49°41′40″N 36°21′33″E / 49.69444°N 36.35917°ECoordinates: 49°41′40″N 36°21′33″E / 49.69444°N 36.35917°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | Chuhuiv Raion[1] |

| Founded | 1640 |

| City rights | 1797 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 55.77 km2 (21.53 sq mi) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 14,254 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 63409 |

| Licence plate | AX, KX, ХА (old), 21 (old) |

Zmiiv (Ukrainian: Зміїв, Russian: Змиёв) is a city in Chuhuiv Raion, Kharkiv Oblast (province) of Ukraine. It hosts the administration of , one of the hromadas of Ukraine.[2] Population: 14,254 (2020 est.)[3]

History[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

The oldest settlement at the location of modern-day Zmiiv dates back to the 1st millennium B.C. The area around Zmiiv saw numerous different people groups during its history, such as the Scythians, Sarmatians, Goths, Huns, Alans, Avars, Polovtsians, Pechenegs, Tatars, and Slavs.

Igor Svyatoslavich, Novgorod-Seversky prince, waged wars with the Polovtsy, founded in 1180 - 1185 years on Donets at the mouth of the river the Zmiiv Settlement.

In the mid-1500s an outpost was built there, and in the 1650s the Cossacks built a fort there to defend the vicinity against the Tatars. Zmiiv was a company town of the Kharkiv regiment from 1669 to 1765. It was ravaged by the Tatars in 1688, 1689, and 1692. Its Cossacks took part in the uprisings led by Ivan Dzykovksy (1670) and Kodratii Bulavin (1707–9).[4]

The new wave of settlement of the Wild Field lands, and in particular the lands of the Slobozhanshchina, dates back to the 1630-50s, when thousands of Ukrainians were forced to flee from massacre after unsuccessful revolts against the Polish authorities. 1640 is the official date of foundation of the city. But in the same year, the Tatars seized the city, which was captured by Cossacks Kondratii Sulima. In the 1650s, to the south of the Zmiiv appeared the Zmiiv Nikolaev Cossack Monastery, which was the castle of the old, wounded and other Cossacks. It is believed that the monastery was a treasure chest; it had 6,000 acres of land and numerous buildings. In 1656 it was sent to the city by the Tsar of Moscow, .[5]

At the end of 17 ct., the Zmiiv was already a large enough settlement, surrounded by posts: Zamost, Zidki, and Sands. And if for some time he was a part of the Chuguev uyezd, then from 1657 he became the center of the newly created Zmiev uyezd. Sources also mention the weapons of the local fortress: in 1668 it had 7 large cast iron guns, 290 cores and a lot of gunpowder, with 2 shafts surrounding it and a system of underground passages. In 1688, 1692 and 1736, Tatar attacks were carried out on the city.[6]

The presence of settlements in Slobozhana under the rule of the Russian tsar and the strong oppression on the part of the church and the cossack elders did not best reflect the mood of the freedom-loving settlers. Thus, in 1668, a rebellion broke out in a number of towns and cities in Slobozhanshchyna, which was headed by Ivan Sirko. During the fighting against government forces, the insurgents burned down the Zmiiv.[7][6] In several clashes the rebels were defeated, many fled to the Right-bank Ukraine. 2 years later, in 1670, some towns in the Slobozhanshchina supported the rebels under the leadership of Stepan Razin, in particular, there were detachments of Zaporizhzhya and Don Cossacks commanded by Stenka Razin associate, Alexei Khromy. And the Zmiiv became the center of rebellion on the local lands. After the tsarist forces managed to suppress the rebellion, several dozen people were hanged on local roads.[8] According to lord-colonel of Kharkiv cossacks regiment Kvitka, the Tatars' raids have stopped since 1736.

In 1788, the Zmiiv Monastery was destroyed by order of the Russian Empress Catherine II.

It was an administrative centre of Zmiev uyezd in Kharkov Governorate of Russian Empire.

In 1891 - 1892, was built here.[9]

A local newspaper is published in the city since November 1930.[10]

During World War II, Zmiev was occupied by the German Army from 22 October 1941 to 17–18 August 1943.[11]

In 1956, a machine-building plant was established here.[9] Between 1976 and 1990, the city was renamed after Klement Gottwald, a Czechoslovak politician, to Gotwald (Ukrainian: Готвальд).[9]

Until 18 July 2020, Zmiiv was the administrative center of Zmiiv Raion. The raion was abolished in July 2020 as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Kharkiv Oblast to seven. The area of Zmiivk Raion was merged into Chuhuiv Raion.[12][13]

Demographics[]

The population as of 1971 was 16600.[14]

In January 1989 the population was 20 031 people.[15][9]

In January 2013 the population was 15 211 people.[16]

Symbols[]

The current coat of arms of the Zmiiv has more than 220 years of history. The coat of arms of the city of the second half of the eighteenth century, 1803 and modern - is eloquent: it depicts a serpent (Ukrainian: змій) with a golden crown on its head.

On September 21, 1781, the coat of arms of the city was not officially approved by the Senate of the Russian Empire and Catherine II in one day with all the coat of arms of the county cities and the provincial center of Kharkiv and Voronezh governorships, because the Zmiiv was not then a county town.

The coat of arms is "old", that is, historical, and made long before its approval. A distinctive feature of the "old" coats of arms was the only field of the shield - with the coat of arms of the city itself (without the coat of arms of the governorate / provincial center at the top). It was officially approved on September 21, 1803 personally by Emperor Alexander I.

The red box of the coat of arms depicts a "golden serpent twisting upwards and a crown worn on its head" showing the name of the city and the abundance of snakes in the vicinity.

In 1863 K. Kene drafted the emblem of the city: On a red shield a golden serpent twisting in a pillar; in the free part of the shield the coat of arms of Kharkiv province; the shield is topped with a silver tower crown and surrounded by gold spikes connected by an Alexander ribbon.

On the coat of arms of the city of the 18th century the artist depicted a creeping snake, unlike the coat of arms of the beginning of the 19th century, which depicts a standing snake. The modern coat of arms was approved by the City Council in the 1990s. It, like the coat of arms of the early 19th century, depicts a snake standing.

Coat of Arms with official description of 1803

1863 Coat of Arms.

The B.Ken Project

Modern coat of arms

Geography[]

Zmiiv is situated on the right bank of the Seversky Donets River at the confluence of the right-hand tributary of the river.[14]

Economy[]

A machine-building plant is the largest company in town. Zmiiv also has a paper mill, dairy plant, food-processing plant, packaging works, construction materials plant, publishing company, and some repair shops.

Transportation[]

Zmiiv is served by the [14][9] on the Southern Railway. The station was opened in 1910. It is served by the commuter rail (also known as elektrichki) connecting Kharkiv, Merefa, and Izium with intermediate stops.

Zmiiv has a bus station, which serves as a terminus for local bus routes. Zmiiv has also a regular bus connection with Kharkiv.

Sports[]

Zmiiv has one soccer club playing in the Kharkiv Oblast Premier League, "Mayak".

Points of interest[]

- Ionospheric Observatory of the Institute of ionosphere (49°40′37″N 36°17′32″E / 49.67694°N 36.29222°E) [1]

Monuments[]

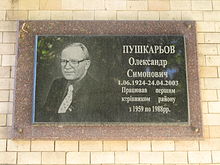

|

|

|

|

| Memorial to the soldiers who died in World War II | Memorial to the Red Army killed in 1918–1921, 1924 | Commemorative plaque of Pushkarev | Monument to fellow countrymen of the heroes of the Soviet Union |

|

|

|

|

| State flag of Ukraine in honor of the 20th anniversary of independence |

A commemorative sign of the Chornobyl tragedy |

Monument to soldiers-internationalists who participated in the Soviet-Afghan war |

Monument twice to the Hero of the Soviet Union Zakhar Slyusarenko |

Gallery[]

Zmijiv skyline

Old building

Zmiiv central hospital

Zmiiv Museum of Local Lore

Church of the Holy Trinity

Zmiiv railway station

Installation "I love Zmiiv"

Zmiiv cliffs

Notable residents[]

- Igor Volk, cosmonaut and test pilot

- Ruslan Polovinko, helicopter pilot and lieutenant, awarded the title of National Hero of Azerbaijan

References[]

- ^ Where did 354 districts disappear to? Anatomy of loud reform, (7 August 2020) (in Ukrainian)

- ^ "Змиевская городская громада" (in Russian). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

- ^ "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Zmiiv // History of Zmievland. Zmiev. 12.25.2018.

- ^ Kolovrat-Butenko Yu. A. Clarification of the date of Zmiev foundation // Zmiev Local Lore. 2017. №1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Змиев // Географическо-статистический словарь: В 5 томах / Сост. П. П. Семёнов. — СПб., 1865. — Т. 2. — С. 281.

- ^ Филарет (Гумилевский Д. Г.) Историко-статистическое описание Харьковской епархии. — Отд. 4. — Х., 1857. — С.191.

- ^ Загоровский В. П. Изюмская черта / В. П. Загоровский. — Воронеж, 1980. — С. 60-61.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Готвальд // Большой энциклопедический словарь (в 2-х тт.). / редколл., гл. ред. А. М. Прохоров. том 1. М., "Советская энциклопедия", 1991. стр.329

- ^ № 3148. Известия Змиевщины // Летопись периодических и продолжающихся изданий СССР 1986 - 1990. Часть 2. Газеты. М., «Книжная палата», 1994. стр.412

- ^ История второй мировой войны 1939—1945 (в 12 тт.) / редколл., гл. ред. А. А. Гречко. том 7. М., Воениздат, 1976. стр.195

- ^ "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 2020-07-18. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Змиев // Большая Советская Энциклопедия. / под ред. А. М. Прохорова. 3-е изд. том 9. М., «Советская энциклопедия», 1972.

- ^ Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность городского населения союзных республик, их территориальных единиц, городских поселений и городских районов по полу

- ^ Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2013 року. Державна служба статистики України. Київ, 2013. стор.98

External links[]

- Cities in Kharkiv Oblast

- Kharkov Governorate

- Cities of district significance in Ukraine

- Cities and towns built in the Sloboda Ukraine