Æthelred the Unready

| Æthelred | |

|---|---|

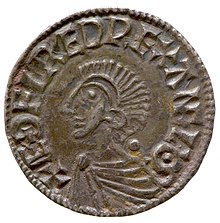

Æthelred in an early thirteenth-century copy of the Abingdon Chronicle | |

| King of the English | |

| Reign | 18 March 978 – 1013 |

| Predecessor | Edward the Martyr |

| Successor | Sweyn Forkbeard |

| Reign | 1014 – 23 April 1016 |

| Predecessor | Sweyn Forkbeard |

| Successor | Edmund Ironside |

| Born | c. 966 England |

| Died | 23 April 1016 (aged about 49) London, England |

| Burial | Old St Paul's Cathedral, London, now lost |

| Spouses | |

| Issue Detail | show

See list |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Edgar, King of England |

| Mother | Ælfthryth |

Æthelred (Old English: Æþelræd, pronounced [ˈæðelræːd];[n 1] c. 966 – 23 April 1016), known as the Unready, was King of the English from 978 to 1013 and again from 1014 until his death in 1016. His epithet does not derive from the modern word "unready", but rather from the Old English unræd meaning "poorly advised"; it is a pun on his name, which means "well advised".

Æthelred was the son of King Edgar and Queen Ælfthryth. He came to the throne at about the age of 12, following the assassination of his older half-brother, Edward the Martyr. His brother's murder was carried out by supporters of his own claim to the throne, although he was too young to have any personal involvement.[citation needed]

The chief problem of Æthelred's reign was conflict with the Danes. After several decades of relative peace, Danish raids on English territory began again in earnest in the 980s. Following the Battle of Maldon in 991, Æthelred paid tribute, or Danegeld, to the Danish king. In 1002, Æthelred ordered what became known as the St. Brice's Day massacre of Danish settlers. In 1013, King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark invaded England, as a result of which Æthelred fled to Normandy in 1013 and was replaced by Sweyn. However, he returned as king for two years after Sweyn's death in 1014. Æthelred's 37-year combined reign was the longest of any Anglo-Saxon king of England, and was only surpassed in the 13th century, by Henry III. Æthelred was briefly succeeded by his son, Edmund Ironside, but he died after a few months and was replaced by Sweyn's son, Cnut. Another of Æthelred's sons, Edward the Confessor, became king in 1042.

Name[]

Æthelred's first name, composed of the elements æðele, "noble", and ræd, "counsel, advice",[1] is typical of the compound names of those who belonged to the royal House of Wessex, and it characteristically alliterates with the names of his ancestors, like Æthelwulf ("noble-wolf"), Ælfred ("elf-counsel"), Eadweard ("rich-protection"), and Eadgar ("rich-spear").[2]

Æthelred's notorious nickname, Old English Unræd, is commonly translated into present-day English as "The Unready" (less often, though less inaccurately, as "The Redeless").[n 2] The Anglo-Saxon noun unræd means "evil counsel", "bad plan", or "folly".[3] It was most often used in reference to decisions and deeds, but once in reference to the ill-advised disobedience of Adam and Eve. The element ræd in unræd is the same element in Æthelred's name that means "counsel" (compare the cognate in the German word Rat). Thus Æþelræd Unræd is an oxymoron: "Noble counsel, No counsel". The nickname has also been translated as "ill-advised", "ill-prepared", thus "Æthelred the ill-advised".[4]

Because the nickname was first recorded in the 1180s, more than 150 years after Æthelred's death, it is doubtful that it carries any implications as to the reputation of the king in the eyes of his contemporaries or near contemporaries.[5][n 3]

Early life[]

Sir Frank Stenton remarked that "much that has brought condemnation of historians on King Æthelred may well be due in the last resort to the circumstances under which he became king."[6] Æthelred's father, King Edgar, had died suddenly in July 975, leaving two young sons behind. The elder, Edward (later Edward the Martyr), was probably illegitimate,[7] and was "still a youth on the verge of manhood" in 975.[8] The younger son was Æthelred, whose mother, Ælfthryth, Edgar had married in 964. Ælfthryth was the daughter of Ordgar, ealdorman of Devon, and widow of Æthelwald, Ealdorman of East Anglia. At the time of his father's death, Æthelred could have been no more than 10 years old. As the elder of Edgar's sons, Edward – reportedly a young man given to frequent violent outbursts – probably would have naturally succeeded to the throne of England despite his young age, had not he "offended many important persons by his intolerable violence of speech and behaviour."[8] In any case, a number of English nobles took to opposing Edward's succession and to defending Æthelred's claim to the throne; Æthelred was, after all, the son of Edgar's last, living wife, and no rumour of illegitimacy is known to have plagued Æthelred's birth, as it might have his elder brother's.[9]

Both boys, Æthelred certainly, were too young to have played any significant part in the political manoeuvring which followed Edgar's death. It was the brothers' supporters, and not the brothers themselves, who were responsible for the turmoil which accompanied the choice of a successor to the throne. Æthelred's cause was led by his mother and included Ælfhere, Ealdorman of Mercia and Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester,[10][11] while Edward's claim was supported by Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Oswald, the Archbishop of York[12] among other noblemen, notably Æthelwine, Ealdorman of East Anglia, and Byrhtnoth, ealdorman of Essex. In the end, Edward's supporters proved the more powerful and persuasive, and he was crowned king at Kingston upon Thames before the year was out.

Edward reigned for only three years before he was murdered by members of his brother's household.[13] Though little is known about Edward's short reign, it is known that it was marked by political turmoil. Edgar had made extensive grants of land to monasteries which pursued the new monastic ideals of ecclesiastical reform, but these disrupted aristocratic families' traditional patronage. The end of his firm rule saw a reversal of this policy, with aristocrats recovering their lost properties or seizing new ones. This was opposed by Dunstan, but according to Cyril Hart, "The presence of supporters of church reform on both sides indicates that the conflict between them depended as much on issues of land ownership and local power as on ecclesiastical legitimacy. Adherents of both Edward and Æthelred can be seen appropriating, or recovering, monastic lands."[7] Nevertheless, favour for Edward must have been strong among the monastic communities. When Edward was killed at Æthelred's estate at Corfe Castle in Dorset in March 978, the job of recording the event, as well as reactions to it, fell to monastic writers. Stenton offers a summary of the earliest account of Edward's murder, which comes from a work praising the life of St Oswald:

On the surface his [Edward's] relations with Æthelred his half-brother and Ælfthryth his stepmother were friendly, and he was visiting them informally when he was killed. [Æthelred's] retainers came out to meet him with ostentatious signs of respect, and then, before he had dismounted, surrounded him, seized his hands, and stabbed him ... So far as can be seen the murder was planned and carried out by Æthelred's household men in order that their young master might become king. There is nothing to support the allegation, which first appears in writing more than a century later, that Queen Ælfthryth had plotted her stepson's death. No one was punished for a part in the crime, and Æthelred, who was crowned a month after the murder, began to reign in an atmosphere of suspicion which destroyed the prestige of the crown. It was never fully restored in his lifetime.

— Stenton 2001, p. 373

Kingship[]

Nevertheless, at first, the outlook of the new king's officers and counsellors seems in no way to have been bleak. According to one chronicler, the coronation of Æthelred took place with much rejoicing by the councillors of the English people.[14] Simon Keynes notes that "Byrhtferth of Ramsey states similarly that when Æthelred was consecrated king, by Archbishop Dunstan and Archbishop Oswald, 'there was great joy at his consecration', and describes the king in this connection as 'a young man in respect of years, elegant in his manners, with an attractive face and handsome appearance'."[14]

Æthelred was between nine and twelve years old when he became king and affairs were initially managed by leading councillors such as Æthelwold, bishop of Winchester, Queen Ælfthryth and Dunstan, archbishop of Canterbury. Æthelwold was especially influential and when he died, on 1 August 984, Æthelred abandoned his early councillors and launched on policies which involved encroachment on church privileges, to his later regret. In a charter of 993 he stated that Æthelwold's death had deprived the country of one "whose industry and pastoral care administered not only to my interest but also to that of all inhabitants of the country."[14]

Ælfthryth enjoyed renewed status in the 990s, when she brought up his heirs and her brother Ordulf became one of Æthelred's leading advisers. She died between 1000 and 1002.[15]

Conflict with the Danes[]

England had experienced a period of peace after the reconquest of the Danelaw in the mid-10th century by King Edgar, Æthelred's father. However, beginning in 980, when Æthelred could not have been more than 14 years old, small companies of Danish adventurers carried out a series of coastline raids against England. Hampshire, Thanet and Cheshire were attacked in 980, Devon and Cornwall in 981, and Dorset in 982. A period of six years then passed before, in 988, another coastal attack is recorded as having taken place to the south-west, though here a famous battle was fought between the invaders and the thegns of Devon. Stenton notes that, though this series of isolated raids had no lasting effect on England itself, "their chief historical importance is that they brought England for the first time into diplomatic contact with Normandy."[16]

During this period, the Normans offered shelter to Danes returning from raids on England. This led to tension between the English and Norman courts, and word of their enmity eventually reached Pope John XV. The pope was disposed to dissolve their hostility towards each other, and took steps to engineer a peace between England and Normandy, which was ratified in Rouen in 991.[17][18]

Battle of Maldon[]

In August 991, a sizeable Danish fleet began a sustained campaign in the south-east of England. It arrived off Folkestone, in Kent, and made its way around the south-east coast and up the River Blackwater, coming eventually to its estuary and occupying Northey Island.[14] About 2 kilometres (1 mile) west of Northey lies the coastal town of Maldon, where Byrhtnoth, ealdorman of Essex, was stationed with a company of thegns. The battle that followed between English and Danes is immortalised by the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon, which describes the doomed but heroic attempt of Byrhtnoth to defend the coast of Essex against overwhelming odds. This was the first of a series of crushing defeats felt by the English: beaten first by Danish raiders, and later by organised Danish armies. Stenton summarises the events of the poem:

For access to the mainland they (the Danes) depended on a causeway, flooded at high tide, which led from Northey to the flats along the southern margin of the estuary. Before they (the Danes) had left their camp on the island[,] Byrhtnoth, with his retainers and a force of local militia, had taken possession of the landward end of the causeway. Refusing a demand for tribute, shouted across the water while the tide was high, Byrhtnoth drew up his men along the bank, and waited for the ebb. As the water fell the raiders began to stream out along the causeway. But three of Byrhtnoth's retainers held it against them, and at last they asked to be allowed to cross unhindered and fight on equal terms on the mainland. With what even those who admired him most called 'over-courage', Byrhtnoth agreed to this; the pirates rushed through the falling tide, and battle was joined. Its issue was decided by Byrhtnoth's fall. Many even of his own men immediately took to flight and the English ranks were broken. What gives enduring interest to the battle is the superb courage with which a group of Byrhtnoth's thegns, knowing that the fight was lost, deliberately gave themselves to death in order that they might avenge their lord."

— Stenton 2001, pp. 376–377

England begins tributes[]

In the aftermath of Maldon, it was decided that the English should grant the tribute to the Danes that they desired, and so a gafol of £10,000 was paid them for their peace. Yet it was presumably the Danish fleet that had beaten Byrhtnoth at Maldon that continued to ravage the English coast from 991 to 993. In 994, the Danish fleet, which had swollen in ranks since 991, turned up the Thames estuary and headed toward London. The battle fought there was inconclusive.

It was about this time that Æthelred met with the leaders of the Danish fleet and arranged an uneasy accord. A treaty was signed that provided for seemingly civilised arrangements between the then-settled Danish companies and the English government, such as regulation of settlement disputes and trade. But the treaty also stipulated that the ravaging and slaughter of the previous year would be forgotten, and ended abruptly by stating that £22,000 of gold and silver had been paid to the raiders as the price of peace.[19] In 994, Olaf Tryggvason, a Norwegian prince and already a baptised Christian, was confirmed as Christian in a ceremony at Andover; King Æthelred stood as his sponsor. After receiving gifts, Olaf promised "that he would never come back to England in hostility."[14] Olaf then left England for Norway and never returned, though "other component parts of the Viking force appear to have decided to stay in England, for it is apparent from the treaty that some had chosen to enter into King Æthelred's service as mercenaries, based presumably on the Isle of Wight."[14]

Renewed Danish raids[]

In 997, Danish raids began again. According to Keynes, "there is no suggestion that this was a new fleet or army, and presumably the mercenary force created in 994 from the residue of the raiding army of 991 had turned on those whom it had been hired to protect."[14] It harried Cornwall, Devon, western Somerset and south Wales in 997, Dorset, Hampshire and Sussex in 998. In 999, it raided Kent, and, in 1000, it left England for Normandy, perhaps because the English had refused in this latest wave of attacks to acquiesce to the Danish demands for gafol or tribute, which would come to be known as Danegeld, 'Dane-payment'. This sudden relief from attack Æthelred used to gather his thoughts, resources, and armies: the fleet's departure in 1000 "allowed Æthelred to carry out a devastation of Strathclyde, the motive for which is part of the lost history of the north."[20]

In 1001, a Danish fleet – perhaps the same fleet from 1000 – returned and ravaged west Sussex. During its movements, the fleet regularly returned to its base in the Isle of Wight. There was later an attempted attack in the south of Devon, though the English mounted a successful defence at Exeter. Nevertheless, Æthelred must have felt at a loss, and, in the Spring of 1002, the English bought a truce for £24,000. Æthelred's frequent payments of immense Danegelds are often held up as exemplary of the incompetency of his government and his own short-sightedness. However, Keynes points out that such payments had been practice for at least a century, and had been adopted by Alfred the Great, Charles the Bald and many others. Indeed, in some cases it "may have seemed the best available way of protecting the people against loss of life, shelter, livestock and crops. Though undeniably burdensome, it constituted a measure for which the king could rely on widespread support."[14]

St. Brice's Day massacre of 1002[]

Æthelred ordered the massacre of all Danish men in England to take place on 13 November 1002, St Brice's Day. No order of this kind could be carried out in more than a third of England, where the Danes were too strong, but Gunhilde, sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, King of Denmark, was said to have been among the victims. It is likely that a wish to avenge her was a principal motive for Sweyn's invasion of western England the following year.[21] By 1004 Sweyn was in East Anglia, where he sacked Norwich. In this year, a nobleman of East Anglia, Ulfcytel Snillingr met Sweyn in force, and made an impression on the until-then rampant Danish expedition. Though Ulfcytel was eventually defeated, outside Thetford, he caused the Danes heavy losses and was nearly able to destroy their ships. The Danish army left England for Denmark in 1005, perhaps because of the losses they sustained in East Anglia, perhaps from the very severe famine which afflicted the continent and the British Isles in that year.[14]

An expedition the following year was bought off in early 1007 by tribute money of £36,000, and for the next two years England was free from attack. In 1008, the government created a new fleet of warships, organised on a national scale, but this was weakened when one of its commanders took to piracy, and the king and his council decided not to risk it in a general action. In Stenton's view: "The history of England in the next generation was really determined between 1009 and 1012...the ignominious collapse of the English defence caused a loss of morale which was irreparable." The Danish army of 1009, led by Thorkell the Tall and his brother Hemming, was the most formidable force to invade England since Æthelred became king. It harried England until it was bought off by £48,000 in April 1012.[22]

Invasion of 1013[]

Sweyn then launched an invasion in 1013 intending to crown himself king of England, during which he proved himself to be a general greater than any other Viking leader of his generation. By the end of 1013 English resistance had collapsed and Sweyn had conquered the country, forcing Æthelred into exile in Normandy. But the situation changed suddenly when Sweyn died on 3 February 1014. The crews of the Danish ships in the Trent that had supported Sweyn immediately swore their allegiance to Sweyn's son Cnut the Great, but leading English noblemen sent a deputation to Æthelred to negotiate his restoration to the throne. He was required to declare his loyalty to them, to bring in reforms regarding everything that they disliked and to forgive all that had been said and done against him in his previous reign. The terms of this agreement are of great constitutional interest in early English History as they are the first recorded pact between a King and his subjects and are also widely regarded as showing that many English noblemen had submitted to Sweyn simply because of their distrust of Æthelred.[23] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

they [the counsellors] said that no lord was dearer to them than their natural (gecynde) lord, if he would govern them more justly than he did before. Then the king sent his son Edward hither with his messengers and bade them greet all his people and said that he would be a gracious (hold) lord to them, and reform all the things which they hated; and all the things which had been said and done against him should be forgiven on condition that they all unanimously turned to him (to him gecyrdon) without treachery. And complete friendship was then established with oath and pledge (mid worde and mid wædde) on both sides, and they pronounced every Danish king an exile from England forever.

— Williams 2003, p. 123

Æthelred then launched an expedition against Cnut and his allies. It was only the people of the Kingdom of Lindsey (modern North Lincolnshire) who supported Cnut. Æthelred first set out to recapture London apparently with the help of the Norwegian Olaf Haraldsson. According to the Icelandic historian, Snorri Sturluson, Ólaf led a successful attack on London bridge with a fleet of ships. He then went on to help Æthelred retake London and other parts of the country. Cnut and his army decided to withdraw from England, in April 1014, leaving his Lindsey allies to suffer Æthelred's revenge. In about 1016 it is thought that Ólaf left to concentrate on raiding western Europe.[24] In the same year, Cnut returned to find a complex and volatile situation unfolding in England.[24] Æthelred's son, Edmund Ironside, had revolted against his father and established himself in the Danelaw, which was angry at Cnut and Æthelred for the ravaging of Lindsey and was prepared to support Edmund in any uprising against both of them.

Death and burial[]

Over the next few months Cnut conquered most of England, while Edmund rejoined Æthelred to defend London when Æthelred died on 23 April 1016. The subsequent war between Edmund and Cnut ended in a decisive victory for Cnut at the Battle of Assandun on 18 October 1016. Edmund's reputation as a warrior was such that Cnut nevertheless agreed to divide England, Edmund taking Wessex and Cnut the whole of the country beyond the Thames. However, Edmund died on 30 November and Cnut became king of the whole country.[25]

Æthelred was buried in Old St Paul's Cathedral, London. The tomb and his monument in the quire at Old St Paul's Cathedral[26] were destroyed along with the cathedral in the Great Fire of London in 1666.[27] A modern monument in the crypt lists his among the important graves lost.[28]

Legislation[]

Æthelred's government produced extensive legislation, which he "ruthlessly enforced".[29] Records of at least six legal codes survive from his reign, covering a range of topics.[30] Notably, one of the members of his council (known as the Witan) was Wulfstan II, Archbishop of York, a well-known homilist. The three latest codes from Æthelred's reign seemed to have been drafted by Wulfstan.[31] These codes are extensively concerned with ecclesiastical affairs. They also exhibit the characteristics of Wulfstan's highly rhetorical style. Wulfstan went on to draft codes for King Cnut, and recycled there many of the laws which were used in Æthelred's codes.[32]

Despite the failure of his government in the face of the Danish threat, Æthelred's reign was not without some important institutional achievements. The quality of the coinage, a good indicator of the prevailing economic conditions, significantly improved during his reign due to his numerous coinage reform laws.[33]

Legacy[]

Later perspectives of Æthelred have been less than flattering. Numerous legends and anecdotes have sprung up to explain his shortcomings, often elaborating abusively on his character and failures. One such anecdote is given by William of Malmesbury (lived c. 1080 – c. 1143), who reports that Æthelred had defecated in the baptismal font as a child, which led St Dunstan to prophesy that the English monarchy would be overthrown during his reign. This story is, however, a fabrication, and a similar story is told of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine Copronymus, another mediaeval monarch who was unpopular among certain of his subjects.[citation needed]

Efforts to rehabilitate Æthelred's reputation have gained momentum since about 1980. Chief among the rehabilitators has been Simon Keynes, who has often argued that our poor impression of Æthelred is almost entirely based upon after-the-fact accounts of, and later accretions to, the narrative of events during Æthelred's long and complex reign. Chief among the culprits is in fact one of the most important sources for the history of the period, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which, as it reports events with a retrospect of 15 years, cannot help but interpret events with the eventual English defeat a foregone conclusion.[citation needed]

Yet, as virtually no strictly contemporary narrative account of the events of Æthelred's reign exists, historians are forced to rely on what evidence there is. Keynes and others thus draw attention to some of the inevitable snares of investigating the history of a man whom later popular opinion has utterly damned. Recent cautious assessments of Æthelred's reign have more often uncovered reasons to doubt, rather than uphold, Æthelred's later infamy. Though the failures of his government will always put Æthelred's reign in the shadow of the reigns of kings Edgar, Æthelstan, and Alfred, historians' current impression of Æthelred's personal character is certainly not as unflattering as it once was: "Æthelred's misfortune as a ruler was owed not so much to any supposed defects of his imagined character, as to a combination of circumstances which anyone would have found difficult to control."[34]

Origin of the jury[]

Æthelred has been credited with the formation of a local investigative body made up of twelve thegns who were charged with publishing the names of any notorious or wicked men in their respective districts. Because the members of these bodies were under solemn oath to act in accordance with the law and their own good consciences, they have been seen by some legal historians as the prototype for the English grand jury.[35] Æthelred makes provision for such a body in a law code he enacted at Wantage in 997, which states:

þæt man habbe gemot on ælcum wæpentace; & gan ut þa yldestan XII þegnas & se gerefa mid, & swerian on þam haligdome, þe heom man on hand sylle, þæt hig nellan nænne sacleasan man forsecgean ne nænne sacne forhelan. & niman þonne þa tihtbysian men, þe mid þam gerefan habbað, & heora ælc sylle VI healfmarc wedd, healf landrican & healf wæpentake.

— Liebermann 1903, pp. 228–232, "III Æthelred" 3.1–3.2

that there shall be an assembly in every wapentake,[n 4] and in that assembly shall go forth the twelve eldest thegns and the reeve along with them, and let them swear on holy relics, which shall be placed in their hands, that they will never knowingly accuse an innocent man nor conceal a guilty man. And thereafter let them seize those notorious [lit. "charge-laden"] men, who have business with the reeve, and let each of them give a security of 6 half-marks, half of which shall go to the lord of that district, and half to the wapentake.

But the wording here suggests that Æthelred was perhaps revamping or re-confirming a custom which had already existed. He may actually have been expanding an established English custom for use among the Danish citizens in the North (the Danelaw). Previously, King Edgar had legislated along similar lines in his Whitbordesstan code:

ic wille, þæt ælc mon sy under borge ge binnan burgum ge buton burgum. & gewitnes sy geset to ælcere byrig & to ælcum hundrode. To ælcere byrig XXXVI syn gecorone to gewitnesse; to smalum burgum & to ælcum hundrode XII, buton ge ma willan. & ælc mon mid heora gewitnysse bigcge & sylle ælc þara ceapa, þe he bigcge oððe sylle aþer oððe burge oððe on wæpengetace. & heora ælc, þonne hine man ærest to gewitnysse gecysð, sylle þæne að, þæt he næfre, ne for feo ne for lufe ne for ege, ne ætsace nanes þara þinga, þe he to gewitnysse wæs, & nan oðer þingc on gewitnysse ne cyðe buton þæt an, þæt he geseah oððe gehyrde. & swa geæþdera manna syn on ælcum ceape twegen oððe þry to gewitnysse.

— Liebermann 1903, pp. 206–214, "IV Edgar" 3–6.2

It is my wish that each person be in surety, both within settled areas and without. And 'witnessing' shall be established in each city and each hundred. To each city let there be 36 chosen for witnessing; to small towns and to each hundred let there be 12, unless they desire more. And everybody shall purchase and sell their goods in the presence a witness, whether he is buying or selling something, whether in a city or a wapentake. And each of them, when they first choose to become a witness, shall give an oath that he will never, neither for wealth nor love nor fear, deny any of those things which he will be a witness to, and will not, in his capacity as a witness, make known any thing except that which he saw and heard. And let there be either two or three of these sworn witnesses at every sale of goods.

The 'legend' of an Anglo-Saxon origin to the jury was first challenged seriously by Heinrich Brunner in 1872, who claimed that evidence of the jury was only seen for the first time during the reign of Henry II, some 200 years after the end of the Anglo-Saxon period, and that the practice had originated with the Franks, who in turn had influenced the Normans, who thence introduced it to England.[36][37] Since Brunner's thesis, the origin of the English jury has been much disputed. Throughout the 20th century, legal historians disagreed about whether the practice was English in origin, or was introduced, directly or indirectly, from either Scandinavia or Francia.[35] Recently, the legal historians Patrick Wormald and Michael Macnair have reasserted arguments in favour of finding in practices current during the Anglo-Saxon period traces of the Angevin practice of conducting inquests using bodies of sworn, private witnesses. Wormald has gone as far as to present evidence suggesting that the English practice outlined in Æthelred's Wantage code is at least as old as, if not older than, 975, and ultimately traces it back to a Carolingian model (something Brunner had done).[38] However, no scholarly consensus has yet been reached.

Appearance and character[]

Æthelred has been described as "a youth of graceful manners, handsome countenance and fine person..."[39] as well as "a tall, handsome man, elegant in manners, beautiful in countenance and interesting in his deportment."[40]

Marriages and issue[]

Æthelred married first Ælfgifu, daughter of Thored, earl of Northumbria, in about 985.[14] Their known children are:

- Æthelstan Ætheling (died 1014)

- Ecgberht Ætheling (died c. 1005)[41]

- Edmund Ironside (King of England, died 1016)

- Eadred Ætheling (died before 1013)

- Eadwig Ætheling (executed by Cnut 1017)

- Edgar Ætheling (died c. 1008)[41]

- Eadgyth or Edith (married Eadric Streona)

- Ælfgifu (married Uhtred the Bold, ealdorman of Northumbria)

- Wulfhild? (married Ulfcytel Snillingr)[42]

- Abbess of Wherwell Abbey?[42]

In 1002 Æthelred married Emma of Normandy, sister of Richard II, Duke of Normandy. Their children were:

- Edward the Confessor (King of England, died 1066)

- Alfred Aetheling (died 1036–37)

- Godgifu or Goda of England (married firstly Drogo of Mantes, Count of Mantes, Valois and the Vexin[43] and secondly Eustace II, Count of Boulogne)[43]

All of Æthelred's sons were named after predecessors of Æthelred on the throne.[44]

See also[]

- Burial places of British royalty

- Cultural depictions of Æthelred the Unready

- House of Wessex family tree

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ Different spellings of this king’s name most commonly found in modern texts are "Ethelred" and "Æthelred" (or "Aethelred"), the latter being closer to the original Old English form Æþelræd. Compare the modern dialect word athel.

- ^ "Ethelred the Redeless" e.g. in Hodgkin, Thomas (1808). The History of England from the Earliest Times to the Norman Conquest. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 373. While rede "counsel" survived into modern English, the negative unrede appears to fall out of use by the 15th century; c.f Richard the Redeless, a 15th-century poem in reference to Richard II of England.

- ^ For this king's forebear of the same name, see Æthelred of Wessex.

- ^ Note that this terms specifies the north and north-eastern territories in England which were at the time largely governed according to Danish custom; no mention is made of the law's application to the hundreds, the southern and English equivalent of the Danish wapentake.

Citations[]

- ^ Bosworth & Toller 1882, p. 781.

- ^ Schröder 1944.

- ^ Bosworth & Toller 1882, p. 1124.

- ^ Williams 2003.

- ^ Keynes 1978, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Stenton 2001, p. 374.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hart 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stenton 2001, p. 372.

- ^ Miller 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Higham 2000, pp. 7-8.

- ^ Stafford 1989, p. 58.

- ^ Phillips 1909.

- ^ Keynes 1980, p. 166.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Keynes 2004.

- ^ Stafford 2004.

- ^ Stenton 2001, p. 375.

- ^ Benham 2020, pp. 189-204.

- ^ Brusher, Joseph. S. J. ""John XV - the Scholarly Pontiff". Popes Through the Ages.

- ^ Stenton 2001, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Stenton 2001, p. 379.

- ^ Stenton 2001, p. 380.

- ^ Stenton 2001, pp. 381–384.

- ^ Stenton 2001, pp. 384–386.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hagland & Watson 2005, pp. 328-333.

- ^ Stenton 2001, pp. 386–393.

- ^ Sinclair 1909, p. 93.

- ^ Keynes 2012, p. 129.

- ^ "Remarkable monuments from Pre-Fire St Paul's - St Paul's Cathedral". www.stpauls.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Wormald 1978, p. 49.

- ^ Liebermann 1903, pp. 216–270.

- ^ Wormald 2004.

- ^ Wormald 1999a, pp. 356–360.

- ^ "Ethelred II". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009.

- ^ Keynes 1986, p. 217.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Turner 1968, pp. passim.

- ^ Turner 1968, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Wormald 1999a, pp. 4–26, especially pp. 7–8 and 17–18.

- ^ Wormald 1999b, pp. 598–599, et passim.

- ^ Florence (of Worcester) 1854, p. 107.

- ^ The Gunnlaugr Saga of Gunnlaugr the Scald

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lawson 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fryde et al. 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barlow 1965, p. 232.

- ^ Barlow 1997, p. 28 and family tree in endpaper.

Sources[]

- Barlow, Frank (1965). "Edward the Confessor's Early Life, Character and Attitudes". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 80 (315): 225–251. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXX.CCCXV.225. JSTOR 560131.

- Barlow, Frank (1997). Edward the Confessor. London: Yale University Press.

- Benham, Jenny (2020). "The earliest arbitration treaty? A reassessment of the Anglo-Norman treaty of 991*". Historical Research. 93 (260): 189–204. doi:10.1093/hisres/htaa001. ISSN 0950-3471.

- Bosworth, Joseph; Toller, T. N. (1882). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford: Clarenden.

- Florence (of Worcester) (1854). The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester: With the Two Continuations; Comprising Annals of English History, from the Departure of the Romans to the Reign of Edward I. Translated by Thomas Forester. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I, eds. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd with corrections ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Hagland, J.R.; Watson, B. (2005). "Fact or folklore: the Viking attack on London Bridge" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 12. London: London Archaeologist Association. 10. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- Hart, Cyril (24 May 2007). "Edward the Martyr". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8515. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Higham, Nick J. (2000). The Death of Anglo-Saxon England. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-2469-6.

- Keynes, Simon (1978), "The Declining Reputation of King Æthelred the Unready", in David Hill (ed.), Ethelred the Unready: Papers from the Millenary Conference, British Archaeological Reports - British Series 59, pp. 227–253

- Keynes, Simon (1980). The Diplomas of King Æthelred 'the Unready' 978–1016. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521227186.

- Keynes, Simon (1986). "A Tale of Two Kings: Alfred the Great and Æthelred the Unready". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Fifth Series 36. 36: 195–217. doi:10.2307/3679065. JSTOR 3679065.

- Keynes, Simon (23 September 2004). "Æthelred II (c. 966x8–1016)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8915. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Keynes, Simon (2012). "The Burial of King Æthelred the Unready at St. Paul's". In David Roffe (ed.). The English and Their Legacy, 900–1200: Essays in Honour of Ann Williams. Boydell Press.

- Lawson, M. K. (23 September 2004). "Edmund II". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8502. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Liebermann, Felix (1903). Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen: in der Ursprache mit Uebersetzung und Erläuterungen. Volume 1. Halle a.S.: Max Niemeyer.

|volume=has extra text (help) - Miller, Sean (1999). "Edward the Martyr". In M. Lapidge; J. Blair; S. Keynes; D. Scragg (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopædia of Anglo-Saxon England. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Phillips, G. E. (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Schröder, Edward (1944). Deutsche Namenkunde: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kunde deutsche Personen- und Ortsnamen [German name customs : Collected essays on the customs of German personal and place names] (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Sinclair, William Macdonald (1909). Memorials of St. Paul's Cathedral. George W. Jacobs & Company.

- Stafford, Pauline (1989). Unification and Conquest: A Political and Social History of England in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. E. Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-6532-6.

- Stafford, Pauline (2004). "Ælfthryth (d. 999x1001)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/194. Retrieved 12 February 2021. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Stenton, Frank Merry (2001). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Turner, Ralph V. (1968). "The Origins of the Medieval English Jury: Frankish, English, or Scandinavian?". The Journal of British Studies. 7 (2): 1–10. doi:10.1086/385549. JSTOR 175292.

- Williams, Ann (2003). Æthelred the Unready: The Ill-Counselled King. ISBN 1-85285-382-4.

- Wormald, Patrick (1978), "Aethelred the lawmaker", in David Hill (ed.), Ethelred the Unready: Papers from the Millenary Conference, British Archaeological Reports - British Series 59, pp. 47–80

- Wormald, Patrick (1999a). Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century. Vol. 1: Legislation and its Limits. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-13496-1.

|volume=has extra text (help) - Wormald, Patrick (1999b). "Neighbors, Courts, and Kings: Reflections on Michael Macnair's Vicini". Law and History Review. 17 (3): 597–601. doi:10.2307/744383. JSTOR 744383.

- Wormald, Patrick (23 September 2004). "Wulfstan (d. 1023)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30098. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading[]

- Cubitt, Catherine (2012). "The politics of remorse: penance and royal piety in the reign of Æthelred the Unready". Historical Research. 85 (228): 179–192. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2011.00571.x.

- Gilbride, M.B. "A Hollow Crown review". Medieval Mysteries.com "Reviews of Outstanding Historical Novels set in the Medieval Period". Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Godsell, Andrew "Ethelred the Unready" in "History For All" magazine September 2000, republished in "Legends of British History" (2008).

- Hart, Cyril, ed. and tr. (2006). Chronicles of the Reign of Æthelred the Unready: An Edition and Translation of the Old English and Latin Annals. The Early Chronicles of England 1.

- Lavelle, Ryan (2008). Aethelred II: King of the English 978–1016 (New ed.). Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 9780752446783.

- Roach, Levi (2016). Æthelred the Unready. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300196290.

- Skinner, Patricia, ed, Challenging the Boundaries of Medieval History: The Legacy of Timothy Reuter (2009), ISBN 978-2-503-52359-0.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Æthelred II of England. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Æthelred the Unready.. |

- 960s births

- 1016 deaths

- 10th-century English monarchs

- 11th-century English monarchs

- Anglo-Saxon warriors

- House of Wessex

- Medieval child rulers

- Monarchs of England before 1066

- Burials at St Paul's Cathedral