Sussex

| Sussex | |

|---|---|

| Historic county | |

Flag of Sussex | |

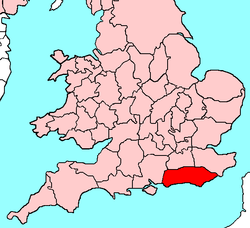

Sussex within the United Kingdom | |

| Area | |

| • 1901 | 1,456.89 square miles (3,773 km2)[3] |

| • 2011 | 1,460.78 square miles (3,783 km2)[3] |

| • Coordinates | 51°N 0°E / 51°N 0°ECoordinates: 51°N 0°E / 51°N 0°E |

| Population | |

| • 1901 | 602,255[3] |

| • 2011 | 1,609,600[4] |

| Density | |

| • 1901 | 413.384 inhabitants per square mile (159.608/km2) |

| • 2011 | 1,101.8 inhabitants per square mile (425.4/km2) |

| History | |

| • Origin | Kingdom of Sussex |

| • Created | 5th century |

| • Succeeded by | East Sussex and West Sussex |

| Status | Historic county (current)[1][2] Ceremonial county (until 1974) |

| Chapman code | SSX |

| Government | |

| • HQ | Chichester or Lewes |

| • Motto | "We wunt be druv" |

| Subdivisions | |

| • Type | Rapes |

| • Units | 1 Chichester • 2 Arundel • 3 Bramber • 4 Lewes • 5 Pevensey • 6 Hastings |

| |

Sussex (/ˈsʌsɪks/), from the Old English Sūþsēaxe (South Saxons), is a historic county in South East England and was formerly an independent medieval kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English Channel, and divided for many purposes into the ceremonial counties of West Sussex and East Sussex.

Brighton and Hove, though part of East Sussex, was made a unitary authority in 1997, and as such, is administered independently of the rest of East Sussex. Brighton and Hove was granted City status in 2000. Until then, Chichester was Sussex's only city. The Brighton and Hove built-up area is the 15th largest conurbation in the UK and Brighton and Hove is the most populous city or town in Sussex. Crawley, Worthing and Eastbourne are major towns, each with a population over 100,000. Sussex has three main geographic sub-regions, each oriented approximately east to west. In the southwest is the fertile and densely populated coastal plain. North of this are the rolling chalk hills of the South Downs, beyond which is the well-wooded Sussex Weald.

Sussex was home to some of Europe's earliest known hominids (Homo heidelbergensis), whose remains at Boxgrove have been dated to 500,000 years ago. Sussex played a key role in the Roman conquest of Britain, with some of the earliest significant signs of a Roman presence in Britain. Local chieftains allied with Rome, resulting in Cogidubnus being given a client kingdom centred on Chichester.[5] The kingdom of Sussex was founded in the aftermath of the Roman withdrawal from Britain. According to legend, it was founded by Ælle, King of Sussex, in AD 477. Around 827, it was annexed by the kingdom of Wessex[6] and subsequently became a county of England. Sussex played a key role in the Norman conquest of England when in 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, landed at Pevensey and fought the decisive Battle of Hastings.

In 1974, the Lord-Lieutenant of Sussex was replaced with one each for East and West Sussex, which became separate ceremonial counties. Sussex continues to be recognised as a geographical territory and cultural region. It has had a single police force since 1968 and its name is in common use in the media.[7] In 2007, Sussex Day was created to celebrate the county's rich culture and history and in 2011 the flag of Sussex was recognised by the Flag Institute. In 2013, Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Eric Pickles formally recognised and acknowledged the continued existence of England's 39 historic counties, including Sussex.[1][2]

Toponymy[]

The name "Sussex" is derived from the Middle English Suth-sæxe, which is in turn derived from the Old English Suth-Seaxe which means (land or people) of the South Saxons (cf. Essex, Middlesex and Wessex). The South Saxons were a Germanic tribe that settled in the region from the North German Plain during the 5th and 6th centuries.

The earliest known usage of the term South Saxons (Latin: Australes Saxones) is in a royal charter of 689 which names them and their king, Noðhelm, although the term may well have been in use for some time before that. The monastic chronicler who wrote up the entry classifying the invasion seems to have got his dates wrong; recent scholars have suggested he might have been a quarter of a century too late.[8]

Three United States counties (in Delaware, New Jersey, and Virginia), and a former county/land division of Western Australia, are named after Sussex.

Symbols[]

The flag of Sussex consists of six gold martlets, or heraldic swallows, on a blue background, blazoned as Azure, six martlets or. Officially recognised by the Flag Institute on 20 May 2011, its design is based on the heraldic shield of Sussex. The first known recording of this emblem being used to represent the county was in 1611 when cartographer John Speed deployed it to represent the Kingdom of the South Saxons. However, it seems that Speed was repeating an earlier association between the emblem and the county, rather than being the inventor of the association. It is now firmly regarded that the county emblem originated and derived from the coat of arms of the 14th-century Knight of the Shire, Sir John de Radynden.[9] Sussex's six martlets are today held to symbolise the traditional six sub-divisions of the county known as rapes.[10]

Sussex by the Sea is regarded as the unofficial anthem of Sussex; it was composed by William Ward-Higgs in 1907, perhaps originally from the lyrics of Rudyard Kipling's poem entitled Sussex. Adopted by the Royal Sussex Regiment and popularised in World War I, it is sung at celebrations across the county, including those at Lewes Bonfire, and at sports matches, including those of Brighton and Hove Albion Football Club and Sussex County Cricket Club.

The county day, called Sussex Day, is celebrated on 16 June, the same day as the feast day of St Richard of Chichester, Sussex's patron saint, whose shrine at Chichester Cathedral was an important place of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages.

Sussex's motto, We wunt be druv, is a Sussex dialect expression meaning "we will not be pushed around" and reflects the traditionally independent nature of Sussex men and women. The round-headed rampion, also known as the "Pride of Sussex", was adopted as Sussex's county flower in 2002.

Geography[]

Landscape[]

The physical geography of Sussex relies heavily on its lying on the southern part of the Wealden anticline, the major features of which are the high lands that cross the county in a west to east direction: the Weald itself and the South Downs. Natural England has identified the following seven national character areas in Sussex:[11]

- South Coast Plain

- South Downs

- Wealden Greensand

- Low Weald

- High Weald

- Pevensey Levels

- Romney Marshes

At 280 m (918 ft), Blackdown is the highest point in Sussex, or county top. With a height of 248 m (814 ft) Ditchling Beacon is the highest point in East Sussex. At 113 kilometres (70 miles) long, the River Medway is the longest river flowing through Sussex. The longest river entirely in Sussex is the River Arun, which is 60 kilometres (37 miles) long. Sussex's largest lakes are man-made reservoirs. The largest is Bewl Water on the Kent border, while the largest wholly within Sussex is Ardingly Reservoir.

Climate[]

The coastal resorts of Sussex and neighbouring Hampshire are the sunniest places in the United Kingdom.[12] The coast has consistently more sunshine than the inland areas: sea breezes, blowing off the sea, tend to clear any cloud from the coast.[13] The sunshine average is approximately 1,900 hours a year; this is much higher than the UK average of 1,340 hours a year. Most of Sussex lies in hardiness zone 8; the exception is the coastal plain west of Brighton, which lies in the milder zone 9.

Rainfall is below average with the heaviest precipitation on the South Downs with 950 mm (37 in) of rainfall per year.[13] The close proximity of Sussex to the Continent of Europe, results in cold spells in winter and hot, humid weather in summer.[13]

The climate of the coastal districts is strongly influenced by the sea, which, because of its tendency to warm up slower than land, can result in cooler temperatures than inland in the summer. In the autumn months, the coast sometimes has higher temperatures.[13] Rainfall during the summer months is mainly from thunderstorms and thundery showers; from January to March the heavier rainfall is due to prevailing south-westerly frontal systems.[13]

In winter, the east winds can be as cold as further inland.[13] Selsey is known as a tornado hotspot, with small tornadoes hitting the town in 1986, 1998 and 2000,[12] with the 1998 tornado causing an estimated £10 million of damage to 1,000 buildings.[12]

Conurbations[]

Most of Sussex's population is distributed in an east-west line along the English Channel coast or on the east-west line of the A272. The exception to this pattern is the 20th century north-south development on the A23-Brighton line corridor, Sussex's main link to London. Sussex's population is dominated by the Brighton/Worthing/Littlehampton conurbation that, with a population of over 470,000, is home to almost 1 in 3 of Sussex's population. According to the ONS urban area populations for continuous built-up areas, these are the 5 largest conurbations (population figures from the 2001 census):

| Rank | Urban Area[14] | Population

(2001 Census)[14] |

Population (2011 Census)[15] | Localities[16] | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brighton/Worthing/Littlehampton | 461,181 | 474,485 | 10 | Sometimes referred to as two Primary Urban Areas - Brighton Urban Area and Worthing Urban Area[17] |

| 2 | Crawley | 180,177 | 180,508 | 6 | Includes approx. 30,000 people living in Surrey

In the 2001 census this urban area included Reigate and Redhill in Surrey but in the 2011 census it did not. East Grinstead was part of this urban area for the 2011 census but it was not for previous censuses. |

| 3 | Hastings/Bexhill | 126,386 | 133,422 | 2 | |

| 4 | Eastbourne | 106,562 | 118,219 | 1 | |

| 5 | Bognor Regis | 62,141 | 63,885 | 1 |

Population[]

The combined population of Sussex as of 2011 is about 1.6 million.[4][nb 1] In 2011, Sussex had a population density of 425 per km2, higher than the average for England of 407 per km2.

The earliest statement as to the population of Sussex is made by Bede, who describes the county as containing in 681 land of 7,000 families; allowing ten to a family (a reasonable estimate at that date), the total population would be 70,000.[18] In 1693 the county is stated to have contained 21,537 houses. The 1801 census found that the population was 159,311. The decline of the Sussex ironworks probably accounts for the small increase of population during several centuries, although after the massacre of St Bartholomew upwards of 1,500 Huguenots landed at Rye, and in 1685, after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, many more refugees were added to the county.[18] The population of Sussex was 550,446 in 1891 and was 605,202 in 1901.[18]

History[]

Beginnings[]

Finds at Eartham Pit in Boxgrove show that the area has some of the earliest hominid remains in Europe, dating back some 500,000 years and known as Boxgrove Man or Homo heidelbergensis. At a site near Pulborough called The Beedings, tools have been found that date from around 35,000 years ago and that are thought to be from either the last Neanderthals in northern Europe or pioneer populations of modern humans.[19] The thriving population lived by hunting game such as horses, bison, mammoth and woolly rhinos.[20] Around 6000 BC the ice sheet over the North Sea melted, sea levels rose and the meltwaters burst south and westwards, creating the English Channel and cutting the people of Sussex off from their Mesolithic kinsmen to the south. Later in the Neolithic period, the area of the South Downs above Worthing was one of Britain's largest and most important flint-mining centres.[21] The flints were used to help fell trees for agriculture. The oldest of these mines, at Church Hill in Findon, has been carbon-dated to 4500 BC to 3750 BC, making it one of the earliest known mines in Britain. Flint tools from Cissbury have been found as far away as the eastern Mediterranean.[22]

Sussex is rich in remains from the Bronze and Iron Ages, in particular the Bronze Age barrows known as the Devil's Jumps and Cissbury Ring, one of Britain's largest hillforts. Towards the end of the Iron Age in 75 BC people from the Atrebates, one of the tribes of the Belgae, a mix of Celtic and German stock, invading and occupying southern Britain.[23] This was followed by an invasion by the Roman army under Julius Caesar that temporarily occupied south-eastern Britain in 55 BC.[23] Soon after the first Roman invasion had ended, the Celtic Regnenses tribe under their leader Commius initially occupied the Manhood Peninsula.[23] Eppillus, Verica and Cogidubnus followed Commius as rulers of the Regnenses[23][24] or southern Atrebates, a region which included most of Sussex, with their capital in the Selsey area.[25][26]

Roman canton[]

A number of archaeologists now think there is a strong possibility that the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43 started around Fishbourne and Chichester Harbour rather than the traditional landing place of Richborough in Kent. According to this theory, the Romans were called to restore the refugee Verica, a king whose capital was in the Selsey and Chichester area,[27] who had been driven out by the Catuvellauni, a tribe based around modern Hertfordshire.[28]

Much of Sussex was a Roman canton of the Regnenses or Regni, probably taking a similar area to the pre-Roman tribal area and kingdom.[29] Its capital was at Noviomagus Reginorum, modern-day Chichester, close to the pre-Roman capital of the area, around Selsey. Sussex was home to the magnificent Roman Palace at Fishbourne, by far the largest Roman residence known north of the Alps. The Romans built villas, especially on the coastal plain and around Chichester, one of the best preserved being that at Bignor. Christianity first came to Sussex at this time, but faded away when the Romans left in the 5th century. The nationally important Patching hoard of Roman coins that was found in 1997 is the latest find of Roman coins found in Britain, probably deposited after 475 AD, well after the Roman departure from Britain around 410 AD.[30]

Saxon kingdom[]

The foundation legend of Sussex is provided by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which states that in the year AD 477 Ælle landed with his three sons.[31][32] Having fought on the banks of the Mearcredesburna,[33] it seems Ælle secured the area between the Ouse and Cuckmere in a treaty.[34] Traditionally this is thought to have been against native Britons, but it may have been to secure the area east of the Saxon Shore fort of Anderida from the influence of the Kingdom of Kent, with whom the South Saxons may have had occasional disputes.[35] Ælle was recognised as the first 'Bretwalda' or overlord of southern Britain. He was probably the most senior of the Anglo-Saxon kings and led the ill-fated campaign against King Arthur at Mount Badon.

By the 7th century at the latest the South Saxon kings were ruling from sites around Selsey, the pre-Roman capital of the area, and the Roman capital of the area, now renamed Chichester, initially with similar borders to the pre-Roman kingdom and Roman canton.[36] For much of the 7th and 8th centuries, Sussex was engaged in conflict with the kingdom of Wessex to its west. King Æðelwealh formed an alliance with Christian Mercia against Wessex, becoming Sussex's first Christian king. With support from St Wilfrid, Sussex became the last major Anglo Saxon kingdom to become Christian. South Saxon and Mercian forces took control of what is now east Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. Cædwalla of Wessex killed Æðelwealh and "ravaged Sussex by fierce slaughter and devastation". The South Saxons forced Cædwalla from Sussex and were able to lead a campaign into Kent, replacing its king. At this time Sussex could have re-emerged into a regional power.[37][38] Shortly afterwards, Cædwalla returned to Sussex, killing its king and oppressing its people, putting them in what Bede called "a worse state of slavery".[39] The South Saxon clergy were put under the control of West Saxon Winchester.[39] Only around 715 was Eadberht of Selsey made the first bishop of the South Saxons, after which further invasion attempts from Wessex ensued.

Following a period of rule by King Offa of Mercia, Sussex regained its independence but was annexed by Wessex around 827 and was fully absorbed into the crown of Wessex in 860,[40][41] which later grew into the kingdom of England.

Norman Sussex[]

The Battle of Hastings was fought in Sussex, the victory that led to the Norman conquest of England. In September 1066, William of Normandy landed with his forces at Pevensey and erected a wooden castle at Hastings, from which they raided the surrounding area.[42][43] The battle was fought between Duke William of Normandy and the English king, Harold Godwinson, who had strong connections with Sussex and whose chief seat was probably in Bosham.[44] After having marched his exhausted army 250 miles (400 km) from Yorkshire, Harold fought the Normans at the Battle of Hastings, where England's army was defeated and Harold was killed. It is likely that all the fighting men of Sussex were at the battle, as the county's thegns were decimated and any that survived had their lands confiscated.[45] William built Battle Abbey at the site of the battle, with the exact spot where Harold fell marked by the high altar.[45]

Sussex experienced some of the greatest changes of any English county under the Normans, for it was the heartland of King Harold and was potentially vulnerable to further invasion.[46] In the immediate aftermath of the Normans' landing at Pevensey and the Battle of Hastings and to put an end to any rebellion, the Norman army destroyed estates and other assets on their route through Sussex, leading to a 40 per cent reduction in Sussex's wealth, a situation worse than any other southern or midland county. By 1086 wealth in Sussex was still 10—25 per cent lower than it had been in 1066.[47]

It was also during the Norman period that Sussex achieved its greatest importance in comparison with other English counties.[48] Sussex was on the main route between England and Normandy, and the lands of the Anglo-Norman nobility in what is now western France. The growth in Sussex's population, the importance of its ports and the increased colonisation of the Weald were all part of changes as significant to Sussex as those brought by the neolithic period, by the Romans and the Saxons.[49] Sussex also experienced the most radical and thorough reorganisation of land in England. The county's existing sub-divisions, known as rapes, were made into castleries and each territory was given to one of William's most trusted barons. Castles were built to defend the territories including at Arundel, Bramber, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings. Sussex's bishop, Æthelric II, was deposed and imprisoned and replaced with William the Conqueror's personal chaplain, Stigand.[50] The Normans also built Chichester Cathedral and moved the seat of Sussex's bishopric from Selsey to Chichester. The Normans also founded new towns in Sussex, including New Shoreham (the centre of modern Shoreham-by-Sea), Battle, Arundel, Uckfield and Winchelsea.[46]

Sussex under the Plantagenets[]

In 1264, the Sussex Downs were the location of the Battle of Lewes, in which Simon de Montfort and his fellow barons captured Prince Edward (later Edward I), the son and heir of Henry III. The subsequent treaty, known as the Mise of Lewes, led to Montfort summoning the first parliament in English history without any prior royal authorisation. A provisional administration was set up, consisting of Montfort, the Bishop of Chichester and the Earl of Gloucester. These three were to elect a council of nine, to govern until a permanent settlement could be reached.[51] During the Hundred Years' War, Sussex found itself on the frontline, convenient both for intended invasions and retaliatory expeditions by licensed French pirates.[8] Hastings, Rye and Winchelsea were all burnt during this period[8] and all three towns became part of the Cinque Ports, a loose federation for supplying ships for the country's security. Also at this time, Amberley and Bodiam castles were built to defend the upper reaches of navigable rivers.[8] One of the impacts of the war and the Black Death, which killed around half of the population of Sussex,[52] was the perceived injustice that led many Sussex people to participate in the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381. Coastal areas suffered most from the Black Death, and took longest to recover. Instead much economic activity in Sussex was focused on the Weald. Merchants moved north from the coastal towns and many Continental craftsmen, fleeing religious persecution, brought their expertise to the timber, iron, clothmaking and glass industries.[53] Economic and social tensions continued for many years as Sussex people were also involved in Jack Cade’s rebellion of 1450, in which Cade may have been killed at Cade Street, near Heathfield. Demands grew more radical in Sussex in 1451 when John and William Merfold advocated rule by common people. They also demanded that Henry VI be deposed and publicly incited the killing of the nobility and clergy.[54]

Early modern Sussex[]

The Wealden iron industry expanded rapidly, especially after the first blast furnace arrived in Sussex 1496, from the Low Countries, which greatly improved efficiency. Skilled Flemish workers moved to Sussex, followed again by Huguenot craftsmen from France, who brought new techniques. The industry was strategically important and flourished into the 17th century, after which it began to decline. It also brought widespread deforestation of parts of the Sussex Weald.[55]

Henry VIII’s separation of the Church of England from Rome and the dissolution of the monasteries led to the demolition of Lewes Priory and Battle Abbey and the sites being given to Henry’s supporters. The shrine to St Richard at Chichester Cathedral was also destroyed. Queen Mary returned England to Catholicism and in Sussex 41 Protestants were burned to death. Under Elizabeth I, religious intolerance continued albeit on a lesser scale, with several people being executed for their Catholic beliefs.[8] In Elizabeth's reign, Sussex was open to the older Protestant forms practised in the Weald as well as the newer Protestant forms coming from Continental Europe; combined with a significant Catholic presence, Sussex was in many ways out of step with the rest of southern England.[56]

Sussex escaped the worst ravages of the English Civil War, although control of the Wealden iron industry was strategically important to both sides. In 1642 there was a skirmish at Haywards Heath when Royalists marching towards Lewes were intercepted by local Parliamentarians. The Royalists were routed with around 200 killed or taken prisoner.[57] Shortly after there were sieges at Chichester and Arundel, and a smaller battle at Bramber Bridge. Despite its being under Parliamentarian control, Charles II was able to journey through the county after the Battle of Worcester in 1651 to make his escape to France from the port of Shoreham.

In 1681 Charles II granted William Penn lands in what became Pennsylvania and Delaware. Amongst those whom he carried to North America as colonists were 200 people from Sussex, mostly Quakers,[58][59] who founded settlements named after places in Sussex including Lewes and Seaford in Sussex County, Delaware and Horsham Township and Chichester in Pennsylvania.

The Sussex coast was greatly modified by the social movement of sea bathing for health which became fashionable among the wealthy in the second half of the 18th century.[46] Resorts developed all along the coast, including at Brighton, Hastings, Worthing, and Bognor.[46]

Late modern and contemporary Sussex[]

Poverty increased and by 1801 Sussex had the highest poor law rates in England, with 37,000 people of its 160,000 population living on the breadline and receiving regular relief.[60] Socially acceptable crimes including protest, riot and collective action and smuggling were commonplace in Sussex and were seen by many as a legitimate way to address grievances and assert freedoms. Sussex became a centre for radicalism.[61] Thomas Paine developed his political ideas in Lewes, and later wrote Common Sense which was influential in the American Revolution.[62] Richard Cobden was a product of Sussex's rural radicalism,[63] and became a campaigner for free trade and peace. Poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was another influential radical from Sussex.

At the beginning of the 19th century agricultural labourers' conditions took a turn for the worse with an increasing amount of them becoming unemployed, those in work faced their wages being forced down.[64] Conditions became so bad that it was even reported to the House of Lords in 1830 that four harvest labourers (seasonal workers) had been found dead of starvation.[64] The deteriorating conditions of work for the agricultural labourer eventually triggered riots, first in neighbouring Kent, and then in Sussex, where they lasted for several weeks, although the unrest continued until 1832 and became known as the Swing Riots.[64][65]

During World War I, on 30 June 1916, the Royal Sussex Regiment took part in the Battle of the Boar's Head at Richebourg-l'Avoué.[66] The day subsequently became known as The Day Sussex Died.[66] Within five hours the 17 officers and 349 men were killed,[66] and 1,000 men were wounded or taken prisoner.[66] In 1918 the terms of the armistice to be offered to Germany at the end of World War I were agreed at a meeting at Danny House, Hurstpierpoint.[67] With the declaration of World War II, Sussex found itself part of the country's frontline with its airfields playing a key role in the Battle of Britain and with its towns being some of the most frequently bombed.[68] Sussex was garrisoned by multiple British and Canadian Army units from 1940 until at least May 1942.[69] During the lead up to the Dieppe Raid and D-Day landings, the people of Sussex were witness to the buildup of military personnel and materials, including the assembly of landing crafts and construction of Mulberry harbours off the county's coast.[70]

In the post-war era, the New Towns Act 1946 designated Crawley as the site of a new town.[71] As part of the Local Government Act 1972, the eastern and western divisions of Sussex were made into the ceremonial counties of East and West Sussex in 1974. Boundaries were changed and a large part of the rape of Lewes was transferred from the eastern division into West Sussex, along with Gatwick Airport, which was historically part of the county of Surrey.

Governance[]

Politics[]

For most of the 20th century Sussex was a Conservative Party stronghold; until the 1997 general election the only seats won by other parties were in the constituencies of Brighton and Brighton Kemptown. In the early 21st century this gradual shift to the left has continued, especially in more urban areas. This has been most notable in Brighton and Hove, where in Brighton Pavilion the UK's first and only Green MP, Caroline Lucas, was elected in 2010 and the UK's first Green-led local authority was elected in 2011. In the House of Commons, the lower house of the UK Parliament, Sussex is represented by 16 MPs. At the 2019 general election, 13 Conservative MPs, 2 Labour and Labour Co-op MPs and 1 Green MP were elected from Sussex constituencies.

Amongst top-tier local authorities, East and West Sussex County Councils are both held by the Conservatives and Brighton and Hove City Council is led by a minority Green administration.[72] Amongst district councils, as of September 2020 the Conservative Party controls 6 local authorities (Adur, Chichester, Horsham, Mid Sussex, Wealden and Worthing), the Lib Dems control 3 (Arun, Eastbourne and Lewes) and the Labour Party controls 2 (Crawley and Hastings). Conservative Katy Bourne is the Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner, having first been elected in 2012. In the 2016 referendum on UK membership of the EU, the people of Sussex voted to leave the EU by the narrowest of margins, by 50.23% to 49.77% or 4,413 votes.[73][74]

From 1290, Sussex returned two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of England. Each county returned two MPs and each borough designated by Royal charter also returned two MPs. After the union with Scotland two members represented the county in the House of Commons of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1832. The Reform Act 1832 led to the disenfranchisement of some of the smaller Sussex boroughs[75] and divided what had been a single county constituency into eastern and western divisions, with two representatives elected for each division.[76] The reforms of the 19th century made the electoral system more representative, but it was not until 1928 that there was universal suffrage.[75]

Law[]

Headquartered in Lewes, Home Office policing in Sussex has been provided by Sussex Police since 1968.[77]

The first-tier Crown Court for all of Sussex is Lewes Crown Court, which has courts in Lewes, Brighton and Hove. Like other first-tier Crown Courts it has its own resident High Court Judge. There is also a third-tier Crown Court at Chichester. The local prison in Sussex for men is Lewes Prison[78] and there is also a Category D prison at Ford.

Administrative divisions[]

Historic sub-divisions[]

A rape is a traditional territorial sub-division of Sussex, formerly used for various administrative purposes.[79] Their origin is unknown, but they appear to predate the Norman Conquest[80] Each rape was split into several hundreds and may be Romano-British or Anglo-Saxon in origin.[81]

At the time of the Norman Conquest, there were four rapes: Arundel, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings. The rape of Bramber was created later in the 11th century and the rape of Chichester was created in the 13th century.

Modern local authority areas[]

Local government in Sussex has been subject to periodic review over time and Sussex is currently divided two counties for ceremonial purposes and for administrative purposes into two county council areas, East and West Sussex, and one unitary authority, the city of Brighton and Hove. There is a two-tier structure for East Sussex and West Sussex with education, social services, libraries, public transport and waste disposal carried out by the county councils and local planning and building control carried out by the district and borough councils.

For the governance of a long narrow territory it became practical to divide the county into two sections. The three eastern rapes of Sussex became east Sussex and the three western rapes became west Sussex. This began in 1504 with separate administrations (Quarter Sessions) for east and west, a situation recognised by the County of Sussex Act 1865. Under the Local Government Act 1888, the two divisions became two administrative counties (along with three county boroughs: Brighton, Hastings and, from 1911, Eastbourne).[82]

| Ceremonial county

(post 1974) |

Shire county / unitary (post 1888, 1997) | Districts (post 1974) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Sussex |

East Sussex UK locator map 2010 |

1. East Sussex | a) Hastings, b) Rother, c) Wealden, d) Eastbourne, e) Lewes |

| 2. Brighton & Hove (unitary) | |||

| West Sussex |  West Sussex UK locator map 2010 |

3. West Sussex | a) Worthing, b) Arun, c) Chichester, d) Horsham, e) Crawley, f) Mid Sussex, g) Adur |

Economy[]

Sussex has considerable variation in income and deprivation. For statistical purposes at the NUTS2 level, the UK Government pairs Sussex with Surrey, a significantly better off region. In 2018 the four Sussex statistical areas at the NUTS3 level had a GDP per head that varied between £18,852 and £33,711 - typically below the UK average of £32,216. This was in contrast to the two areas in Surrey, which had a GDP per head of £37,429 and 42,433.[83] There is also serious deprivation in Sussex comparable to the most deprived UK inner city areas. Some areas of Sussex are in the top 5 per cent most deprived in the UK and, in some areas, two-thirds of children are living in poverty.[84] In 2011, two Local Enterprise Partnerships were formed to improve the economy in Sussex. These were the Coast to Capital LEP, covering West Sussex, Brighton and Hove and the Lewes district in the west of East Sussex, as well as parts of Surrey and South London; and the South East LEP, which covers the local authority area of East Sussex, as well as Kent and Essex. In the most populous part of Sussex, around the Brighton and Hove Built-up area, the Greater Brighton City Deal was formed to enable the area to fulfil its economic potential, into one of the highest performing urban economies in the UK.[85]

Tourism in Sussex is well-established, and includes seaside resorts and the South Downs National Park. Brighton and Hove has a high density of businesses involved in media, particularly digital or "new media"; since the 1990s Brighton has been referred to as "Silicon Beach".[86] The Greater Brighton City Deal seeks to develop Brighton's creative-tech cluster under the name Tech City South.[85] The University of Sussex and the University of Brighton provide employment for many more. A large part of the county, centred on Gatwick Airport has been recognised as a key economic growth area for South East England[87] whilst reasonable rail connections allow many people to work in London. Several large companies are based in Sussex including American Express (Brighton),[88] The Body Shop (Littlehampton), Bowers & Wilkins (Worthing), Hastings Insurance and Park Holidays UK (Bexhill), Ricardo plc (Shoreham-by-Sea), Rolls-Royce Motor Cars (Goodwood), Thales UK (Crawley), Alfa Laval (Eastbourne) and Virgin Atlantic (Crawley).

The Sussex Weald had an iron working industry from the Iron Age until the 19th century. The glass making industry started on the Sussex/Surrey border throughout the late medieval period until the 17th century.[89] Agriculture in Sussex depended on the terrain, so in the sticky clays and acid sands of the Sussex Weald, pastoral and mixed farming took place, with sheep farming being common on the chalk downland. Fishing fleets continue to operate along the coast, notably at Rye and Hastings. There are working harbours at Rye, Hastings, Newhaven and Shoreham; whilst Pagham, Eastbourne and Chichester harbours cater for leisure craft, as does Brighton Marina. The Mid Sussex area had a thriving clay industry in the early 20th century.

Education[]

The oldest university in Sussex is the research intensive University of Sussex, founded in 1961[90] at Falmer in Brighton, the first new university in England since World War II. The University consistently ranks among the top 20 universities in the UK.[91] It is home to the renowned Institute of Development Studies and the Science Policy Research Unit, alongside over 40 other established research centres.[92][93]

In 1992 it was joined by the University of Brighton (with campuses in Brighton, Eastbourne and Hastings) and in 2005 by the University of Chichester (with campuses in Chichester and Bognor Regis).[94] Validated by University of the Arts London, higher education is also provided at Greater Brighton Metropolitan College, whose campuses in Brighton, Worthing and Shoreham-by-Sea are referred to as MET University Centre.[95]

The Prebendal School in Chichester is the oldest known school in Sussex[96] and probably dates to when the Normans moved the Sussex bishopric from Selsey to Chichester Cathedral in the 11th century.[96] Primary and secondary education in the state sector in Sussex is provided by its three local education authorities of East and West Sussex County Councils and Brighton and Hove City Council. Sussex also has some of the best-known independent schools in England including Christ's Hospital School, Brighton College, Eastbourne College, Lancing College and Roedean School.

Healthcare[]

The Sussex County Hospital (now the Royal Sussex County Hospital) was founded in 1828 at Brighton[97] whilst the Sussex County Mental Asylum (later 'St. Francis Hospital' and now the Princess Royal Hospital) was founded in 1859 in the centre of county at Haywards Heath.[98] Sussex's first medical school, the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, was set up in 2002. In 2011 the four Sussex NHS primary care trusts (PCTs) joined forces to become NHS Sussex.[99] The Major Trauma Centre at the Royal Sussex County Hospital is the Major Trauma Centre for Sussex with the Sussex's other hospitals acting as trauma units. It is one of only five major trauma centres across the NHS's South of England area.[100] The hospital also houses the Sussex Cancer Centre which serves most of Sussex.[101][102]

Culture[]

Sussex has a centuries-old reputation for being separate and culturally distinct from the rest of England.[103] The people of Sussex have a reputation for independence of thought [104] and have an aversion to being pushed around, as expressed through the Sussex motto, We wunt be druv. Sussex is known for its strong tradition of bonfire celebrations and its proud musical heritage. Sussex in the first half of the 20th century was a major centre for modernism, and saw many radical artists and writers move to its seaside towns and countryside.[105]

The county is home to the Brighton Festival and the Brighton Fringe, England's largest arts festival.[106] Brighton Pride is one of the UK's largest and oldest gay pride parades and other pride events take place at most other major towns including Crawley,[107] Eastbourne,[108] Hastings[109] and Worthing. Chichester is home to the Chichester Festival Theatre and Pallant House Gallery.

Architecture[]

Sussex's building materials reflect its geology, being made of flint on and near the South Downs and sandstone in the Weald.[110] Brick is used across the county.[110]

Typically conservative and moderate,[111] the architecture of Sussex also has elaborate and eccentric buildings rarely matched elsewhere in England including the Saxon Church of St Mary the Blessed Virgin, Sompting, Castle Goring, which has a front and rear of entirely different styles and Brighton's Indo-Saracenic Royal Pavilion.

Dialect[]

Historically, Sussex has had its own dialect with regional differences reflecting its cultural history. It has been divided into variants for the three western rapes of West Sussex, the two eastern rapes of Lewes and Pevensey and an area approximate to the easternmost rape of Hastings.[103][112] The Sussex dialect is also notable in having an unusually large number of words for mud, in a way similar to the popular belief which exists that the Inuit have an unusually large number of words for snow.[113]

Literature[]

Writers born in Sussex include the Renaissance poet Thomas May and playwrights Thomas Otway, and John Fletcher. One of the most prolific playwrights of his day, Fletcher is thought to have collaborated with Shakespeare. Notable Sussex poets include William Collins, William Hayley, Percy Bysshe Shelley,[114] Richard Realf, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt,[115] Edward Carpenter and John Scott. Other writers from Sussex include Sheila Kaye-Smith, Noel Streatfeild, Patrick Hamilton, Rumer Godden, Hammond Innes, Angus Wilson, Maureen Duffy, Angela Carter, William Nicholson, Peter James, Kate Mosse and Alex Preston.

In addition there are writers, who while they were not born in Sussex had a strong connection. This includes Charlotte Turner Smith, William Blake, Alfred Tennyson, H.G. Wells, Hilaire Belloc, John Cowper Powys, Arthur Conan Doyle, Henry James, E.F. Benson, James Herbert and AA Milne, who lived in Ashdown Forest for much of his life and set his Winnie-the-Pooh stories in the forest. Sussex has been home to four winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature: Rudyard Kipling spent much of his life in Sussex, living in Rottingdean and later at Burwash.[116] Irishman W.B. Yeats spent three winters living with American poet Ezra Pound at Colemans Hatch in the Ashdown Forest[117] and towards the end of his life spent much time at Steyning and Withyham;[118] John Galsworthy spent much of his life in Bury in the Sussex Downs;[119] and Harold Pinter lived in Worthing in the 1960s.[120]

Music[]

Sussex's rich musical heritage encompasses folk, classical and popular genres amongst others. Composed by William Ward-Higgs, Sussex by the Sea is the county's unofficial anthem.[121] Passed on through oral tradition, many of Sussex's traditional songs may not have changed significantly for centuries, with their origins perhaps dating as far back as the time of the South Saxons.[103] William Henry Hudson compared the singing of the Sussexians with that of the Basques and the Tehuelche people of Patagonia, both peoples with ancient cultures.[122] The songs sung by the Copper Family, Henry Burstow, Samuel Willett, Peter and Harriett Verrall, David Penfold and others were collected by John Broadwood and his niece Lucy Broadwood, Kate Lee and composers Ralph Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth.[121][123] Sussex also played a major part in the folk music revival of the 1960s and 1970s with various singers including George 'Pop' Maynard, Scan Tester, Tony Wales and the sisters Dolly and Shirley Collins.[121]

Sussex has also been home to many composers of classical music including Thomas Weelkes, John Ireland, Edward Elgar, Frank Bridge, Sir Hubert Parry and Ralph Vaughan Williams, who played a major part in recording Sussex's traditional music.[121] While Glyndebourne is one of the world's best known opera houses, the county is home to professional orchestras the Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra[124] and the Worthing Symphony Orchestra.[125]

In popular music, Sussex has produced artists including Leo Sayer, The Cure, The Levellers, Brett Anderson, Keane, The Kooks, The Feeling, Rizzle Kicks, Conor Maynard, Tom Odell, Royal Blood, Rag'n'Bone Man, Celeste and Architects. In the 1970s, Sussex was home to Phun City,[126] the UK's first large-scale free music festival and hosted the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest which propelled ABBA to worldwide fame. Major festivals include The Great Escape Festival[127] and Glyndebourne Festival Opera.

Religion[]

Christianity is the predominant religion in Sussex with 57.8 per cent of the population identifying as Christian in the 2011 census.[128] Other results from the 2011 census are: 1.4 per cent as Muslim, 0.7 per cent as Hindu and 30.5 per cent as having no religion.[128]

Sussex has been a single diocese of the established church since the eighth century, after St Wilfrid founded Selsey Abbey on land granted by King Æðelwealh, Sussex's first Christian king. The Normans moved the location of Sussex's cathedral to Chichester in 1075. Since 1965 Arundel Cathedral has been the seat of the Roman Catholic Bishops of Arundel and Brighton, which covers Sussex and Surrey. The established church and the Catholic Church were historically strongest in western and southern areas.[129] In contrast, Protestant non-conformity was historically strongest in areas furthest from diocesan authorities in Chichester, in the south-west.[130][131] This included in the Weald and in the east, where there were also links to Protestant northern Europe.[132][131] St Richard of Chichester is Sussex's patron saint.

According to the 2011 census there were about 23,000 Muslims in Sussex, constituting 1.4 per cent of the population. Within Sussex, Crawley had the highest proportion of Muslims with 7.2 per cent of the population.[128]

Jewish people have been recorded as living in Sussex since the 12th century and are first mentioned in 1179/80 pipe roll for Chichester. A considerable Jewish community existed in Chichester by 1186. All Sussex's Jews would have been expelled in 1290 when Edward I of England issued the Edict of Expulsion. A Jewish population had returned to Sussex by the late 18th century in Brighton and Arundel.

A wide variety of non-traditional religious and belief groups have bases in and around East Grinstead.[133][134][135] Groups include the Church of Scientology at Saint Hill Manor, Opus Dei, the Rosicrucian Order, the Pagan Federation and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons).[n 1]

Science[]

Pell's equation and the Pell number are both named after 17th century mathematician John Pell. Pell is sometimes credited with inventing the division sign, which has also been attributed to Swiss mathematician Johann Heinrich Rahn, one of his students. In the 19th century, geologist and palaeontologist Gideon Mantell began the scientific study of dinosaurs. In 1822 he was responsible for the discovery and eventual identification of the first fossil teeth, and later much of the skeleton of Iguanodon. Braxton Hicks contractions are named after John Braxton Hicks, the Sussex doctor who in 1872 first described the uterine contractions not resulting in childbirth.

In the 20th century, Frederick Soddy won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on radioactive substances, and his investigations into the origin and nature of isotopes.[136] Frederick Gowland Hopkins shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1929 with Christiaan Eijkman, for discovering the growth-stimulating vitamins.[137] Martin Ryle shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974[138] with Cornishman Antony Hewish, the first Nobel prize awarded in recognition of astronomical research. While working at the University of Sussex, Harold Kroto won the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Richard Smalley and Robert Curl from Rice University in the US for the discovery of fullerenes.[139] David Mumford is a mathematician known for distinguished work in algebraic geometry and then for research into vision and pattern theory. He won the International Mathematical Union's Fields Medal in 1974 and in 2010 was awarded the United States National Medal of Science.

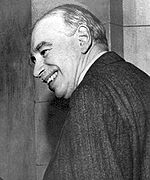

In the social sciences, Sussex was home to economist John Maynard Keynes from 1925 to 1946. The founding father of Keynesian economics, he is widely considered to be one of the founders of modern macroeconomics and the most influential economist of the 20th century.[140][141][142][143] David Pilbeam won the 1986 International Prize from the Fyssen Foundation.[144]

In the early 20th century, Sussex was at the centre of one of what has been described as 'British archaeology's greatest hoax'.[145] Bone fragments said to have been collected in 1912 were presented as the fossilised remains of a previously unknown early human, referred to as Piltdown Man. In 1953 the bone fragments were exposed as a forgery, consisting of the lower jawbone of an orangutan deliberately combined with the skull of a fully developed modern human. From 1967 to 1979, Sussex was home to the Isaac Newton Telescope at the Royal Greenwich Observatory in Herstmonceux Castle.

Sport[]

Sussex has a centuries-long tradition of sport. Sussex has played a key role in the early development of both cricket and stoolball. Cricket is recognised as having been formed in the Weald and Sussex is where cricket was first recorded as being played by men (in 1611),[146] and by women (in 1677),[147] as well as being the location of the first reference to a cricket bat (in 1622)[148] and a wicket (in 1680).[149] Founded in 1839, Sussex CCC is England's oldest county cricket club and is the oldest professional sports club in the world.[150] Slindon Cricket Club dominated the sport for a while in the 18th century. The cricket ground at Arundel Castle traditionally plays host to a Duke of Norfolk's XI which plays the national test sides touring England.[151][152] Founded in 1971, the Sussex Cricket League is believed to be the largest adult cricket league in the world, with 335 teams in 2018.[153] Referred to as Sussex's 'national' sport[154] and a Sussex game or pastime,[155][156] Sussex may be where the sport of stoolball originated and is where the sport was formalised in the 19th century and its revival took place in the early 20th century.

Sussex is represented in the Premier League by Brighton & Hove Albion and in the Football League by Crawley Town. Brighton has been a League member since 1920, whereas Crawley was promoted to the League in 2011. Brighton & Hove Albion play in the FA Women's Super League and Lewes play in the FA Women's Championship. Sussex has had its own football association, since 1882[157] and its own football league, which has since expanded into Surrey, since 1920.[158] In horse racing, Sussex is home to Goodwood, Fontwell Park, Brighton and Plumpton. The All England Jumping Course show jumping facility hosts the British Jumping Derby[159] and the Royal International Horse Show. Eastbourne Eagles speedway team race in the SGB Championship.

Cuisine[]

The historic county is known for its "seven good things of Sussex".[160][161][162] These seven things are Pulborough eel, Selsey cockle, Chichester lobster, Rye herring, Arundel mullet, Amberley trout and Bourne wheatear. Sussex is also known for Ashdown Partridge Pudding, Chiddingly Hot pot, Sussex Bacon Pudding, Sussex Hogs' Pudding, Huffed Chicken, Sussex Churdles, Sussex Shepherds Pie, Sussex Pond Pudding,[163] Sussex Blanket Pudding, Sussex Well Pudding, and Chichester Pudding. Sussex is also known for its cakes and biscuits known as Sussex Plum Heavies [164] and Sussex Lardy Johns, while banoffee pie was first created in 1972 in Jevington.[165][166]

The county has vineyards and a long history of brewing of beer. It is home to the 18th century beer brewers, Harveys of Lewes as well as many more recently established breweries.[167] There are also many cider makers in Sussex, Hunts Sussex Cider[168] and SeaCider[169] are the largest cider producers. In recent decades Sussex wines have gained international acclaim winning awards including the 2006 Best Sparkling Wine in the World at the Decanter World Wine Awards.[170] Many vineyards make wines using traditional Champagne varieties and methods,[171] and there are similarities between the topography and chalk and clay soils[172] of Sussex downland and that of the Champagne region which lies on a latitude 100 miles (161 km) to the south.[171][173]

Visual arts[]

Some of the earliest known art in Sussex is the carvings in the galleries of the Neolithic flint mines at Cissbury on the South Downs near Worthing.[174] From the Roman period, the palace at Fishbourne has the largest in situ collection of mosaics in the UK,[175] while the villa at Bignor contains some of the best preserved Roman mosaics in England.[176]

Dating from around the 12th century, the 'Lewes Group' of wall paintings can be found in several churches across the centre of Sussex, some of which are celebrated for their age, extent and quality. Of uncertain origin, the Long Man of Wilmington is Europe's largest representation of the human form.[177]

In the late 18th century three men commissioned important works of the county which ensured that its landscapes and daily life were captured onto canvas. William Burrell of Knepp Castle commissioned Swiss-born watercolourist Samuel Hieronymus Grimm to tour Sussex, producing 900 watercolours of the county's buildings.[178] George Wyndham, 3rd Earl of Egremont of Petworth House was a patron of painters such as JMW Turner and John Constable.[179] John 'Mad Jack' Fuller also commissioned Turner to make a series of paintings which resulted in thirteen finished watercolours of Fuller's house at Brightling and the area around it.[180]

In the 19th century landscape watercolourist Copley Fielding lived in Sussex and illustrator Aubrey Beardsley and painter and sculptor Eric Gill were born in Brighton. Gill went on to found an art colony in Ditchling known as The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, which survived until 1989. The 1920s and 1930s saw the creation of some of the best-known works by Edward Burra who was known for his work of Sussex, Paris and Harlem[181] and Eric Ravilious who is known for his paintings of the South Downs.[182]

In the early 20th century Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, both members of the Bloomsbury Group, lived and worked at Charleston Farmhouse near Firle.[183] Sussex also became a major centre for surrealism in the early 20th century.[184] At West Dean, Edward James was patron to artists including Salvador Dalí and René Magritte[184][185] while at Farley Farm House near Chiddingly the home of Roland Penrose and Lee Miller was frequented by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, Henry Moore, Eileen Agar, Jean Dubuffet, Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst.[184][186] Both collections form one of the most important bodies of Surrealist art in Europe.[187]

Notable people[]

See also[]

- Flag of Sussex

- Coat of arms of Sussex

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Sussex

- List of High Sheriffs of Sussex

- Custos Rotulorum of Sussex - Keepers of the Rolls

- Sussex (UK Parliament constituency) - Historical list of MPs for Sussex constituency

- East Sussex

- Geology of East Sussex

- West Sussex

- Kingdom of Sussex

- Sussex by the Sea

- Recreational walks in East Sussex

- Sussex County Cricket Club

- Twitten

- Bluebell Railway (Steam Heritage railway)

- The Sussex Newspaper

- Royal Sussex Regiment

- Sussex Police

- Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner

- Stoolball

Footnotes[]

Notes

- ^ Combined population of local authority areas of Brighton and Hove (273,400), East Sussex, (527,200) and West Sussex (808,900)

- ^ The London England Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is located 3 miles (5 km) north of East Grinstead, just over the Surrey border.

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Eric Pickles: celebrate St George and England's traditional counties". Department for Communities and Local Government. 23 April 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kelner, Simon (23 April 2013). "Eric Pickles's championing of traditional English counties is something we can all get behind". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c National Statistics - 200 Years of the Census in Sussex

- ^ Jump up to: a b Office for National Statistics. "Census 2011 result shows increase in population of the South East". Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ "Sussex, historical county, England". Britannica.com. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Edwards, Heather (2004). "Ecgberht [Egbert] (d. 839), king of the West Saxons in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- ^ "BBC News - Sussex". BBC. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Lowerson, John (1980). A Short History of Sussex. Folkestone: Dawson Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7129-0948-8.

- ^ "The Sussex County Flag". The Sussex County Flag. December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Sussex Martlets". The Sussex County Flag. December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "South East and London National Character Area map". Natural England. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Southern England: climate". Met Office. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Weather and Climate in Sussex". Visit Sussex. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Census 2001: Key Statistics for urban areas in the South East" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "2011 Census - Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ KS01 Usual resident population Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas Office for National Statistics. Hectares converted into km2

- ^ "Primary Urban Areas and Travel to Work Area Indicators: Updating the evidence base on cities". Department for Communities and Local Government. 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sussex". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ McGourty, Christine (23 June 2008). "'Neanderthal tools' found at dig". BBC News.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (23 June 2008). "Neanderthal tools reveal advanced technology". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009.

- ^ Kerridge & Standing 2000, p. 10.

- ^ "Prehistory: The Downs Above Steyning". Steyning Museum. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Armstrong. A History of Sussex. Ch. 3.

- ^ Wacher 2020, p. 255

- ^ Laycock 2012

- ^ Cunliffe. Iron Age communities in Britain. p. 169.

- ^ Wacher 2020, p. 255

- ^ Osprey Publishing - Military History Books - The Roman Invasion of Britain Archived 22 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Laycock 2012

- ^ White, Sally; et al. (1999). "A Mid-Fifth Century Hoard of Roman and Pseudo-Roman Material from Patching, West Sussex" (PDF). Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 88–93. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Welch 1992, p. 9.

- ^ ASC Parker MS. 477AD.

- ^ ASC 485 Parker MS: This year Ælle fought with the Welsh nigh Mecred's- Burnsted.

- ^ Brandon 1978, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Laycock 2012

- ^ Laycock 2012

- ^ Kirby 2000, p. 114

- ^ Venning 2013, pp. 45–46

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brandon 1978, p. 32

- ^ Higham & Ryan 2013, p. 324

- ^ Kirby 2000, p. 169

- ^ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 79–89

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, pp. 198–199; Orderic, vol. 2, pp. 168–171

- ^ "Victoria County History A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 4, The Rape of Chichester".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Seward, Desmond (1995). Sussex. London: Random House. pp. 5–7. ISBN 0-7126-5133-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Brandon, Peter (2009). The Shaping of the Sussex Landscape. Snake River Press.

- ^ "Brentry - How Norman rule reshaped England - England is indelibly European". The Economist. 24 December 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Armstrong 1974, p. 43

- ^ Armstrong 1974, p. 43

- ^ Kelly, S.E (1998). Anglo-Saxon Charters VI, Charters of Selsey. OUP for the British Academy. ISBN 0-19-726175-2.

- ^ Powicke, F. M. (1962) [1953], The Thirteenth Century: 1216-1307 (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press

- ^ Broadberry, Stephen; Campbell, Bruce M.S.; van Leeuwen, Bas (27 May 2010). "English Medieval Population: Reconciling Time Series and Cross Sectional Evidence" (PDF) (PDF). University of Warwick. p. 9. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Payton 2017, pp. 85-86

- ^ Mate 1992, p. 667

- ^ Payton 2017, pp. 85-89

- ^ Dimmock, Quinn & Hadfield 2013, p. 205.

- ^ "1642: Civil War in the South East". Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Lower. Worthies of Sussex. p. 341

- ^ Smith Futhey & Cope 1995, p. 21

- ^ Payton 2017, p. 118

- ^ Payton 2017, pp. 119-120

- ^ Thomas 2020, p. 166

- ^ Payton 2017, p. 120

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Harrison. The common people. pp. 249-253

- ^ Horspool. The English Rebel. pp. 339 -340

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The Day Sussex Died". Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Danny House - History". Danny House. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Kim Leslie and Marlin Mace. Sussex Defences in the Second World War in Kim Leslie. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. pp. 118-119.

- ^ Collier, Basil (1957). The Defence of the United Kingdom. London: HMSO. pp. 219, 229, 293.

- ^ Brandon. Sussex. pp. 302-309.

- ^ "Select Committee on Transport, Local Government and the Regions: Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence. Supplementary memorandum by Crawley Borough Council (NT 15(a))". United Kingdom Parliament Publications and Records website. The Information Policy Division, Office of Public Sector Information. 2002. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ Doherty-Cove, Jody (21 July 2020). "Green Party to Take Over Brighton Council from Labour". The Argus. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "RESULT: Sussex votes to leave by majority of just 4,400 votes". West Sussex County Times. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "EU referendum: Sussex votes narrowly for Brexit". BBC. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richard Childs. Parliamentary Representation in Leslies, An Historical Atlas of Sussex. pp. 72-73.

- ^ Horsfield. The History, Antiquities and Topography of the County of Sussex. Volume II. Appendix pp. 23-75.

- ^ "Sussex Police Force". Retrieved 7 August 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Lewes Crown Court & Prison". Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rape". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 90.

- ^ The origin was still reported as "contested" as late as 1942 (Helen Maud Cam (preface dated 1942), Liberties & communities in medieval England: Collected Studies in Local Administration and Topography, 1944:193).

- ^ Mawer, Allen, F. M. Stenton with J. E. B. Gover (1930) [1929]. Sussex - Part I and Part II. English Place-Name Society.

- ^ CONNECTIONS 12 .pdf Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Regional gross domestic product all NUTS level regions". Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Report Shows 'Serious Deprivation' in Sussex". Sussex Community Foundation. November 2013. Archived from the original on 26 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Greater Brighton City Deal" (PDF) (PDF). Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Brighton's Silicon Beach tech cluster finally breaks shore".

- ^ "Gatwick Diamond". Mid Sussex District Council. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "3000+ jobs safeguarded with American Express decision". Brighton Business. 6 September 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Brandon. Sussex. pp. 175 -176.

- ^ "University of Sussex - About Us". University of Sussex. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "University of Sussex". 16 July 2015.

- ^ Unit, SPRU - Science Policy Research. "SPRU - Science Policy Research Unit : University of Sussex". www.sussex.ac.uk.

- ^ "For international development research, teaching and communications".

- ^ "Our History". University of Chichester. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "MET University Centre". Greater Brighton Metropolitan College. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "History and Tradition". The Prebendal School. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "Royal Sussex County Hospital - History". Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Sussex County Asylum, St Francis Hospital". The Time Chamber. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Our role in the NHS". NHS Sussex. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Five major trauma centres named in south of England". BBC. 2 April 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Sussex Cancer Centre". Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Sussex Cancer Network - About Us". Sussex Cancer Network. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hare, Chris (1995). A History of the Sussex People. Worthing: Southern Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-9527097-0-1.

- ^ "A Cultural Strategy for East Sussex County Council" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Dr Hope Wolf's exhibition focusing on Sussex modernism". Sussex Life. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ James, Ben (4 October 2013). "Brighton fringe celebrates best year yet (From The Argus)". Theargus.co.uk. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Dunford, Mark (22 June 2021). "Crawley Pride 2021: When is it? Who is performing? What will there be to do? - All you need to know". Crawley Observer. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Eastbourne Pride". Eastbourne Pride. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Hastings Pride". Hastings Pride. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nairn, Ian and Nikolaus Pevsner (1965). The Buildings of England - Sussex. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-300-09677-4.

- ^ Nairn, Ian and Nikolaus Pevsner (1965). The Buildings of England - Sussex. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-300-09677-4.

- ^ Roper, Jonathan (2007). "Sussex glossarists and their illustrative quotations" (PDF). Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ Collins, Sophie (2007). A Sussex Miscellany. Alfriston: Snake River Press. ISBN 978-1-906022-08-2.

- ^ "Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)". BBC. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Biography: Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840-1922)". Fitzwilliam Museum. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Kipling.s Sussex: The Elms". Kipling.org.

- ^ Longenbach, James (10 January 1988). "The Odd Couple - Pound and Yeats Together". New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ Ross, David A. (2009). Critical Companion to William Butler Yeats: A Literary Reference to His Life. Infobase Publishing. pp. 27, 600. ISBN 978-0816058952.

- ^ "Other writers". South Downs National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ Bensky, Larry (1966). "Interviews: Harold Pinter, The Art of Theater No. 3" (PDF). Paris Review. Archived from the original on 1 January 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Weeks, Marcus (2008). Sussex Music. Alfriston: Snake River Press. ISBN 978-1-906022-10-5.

- ^ Hudson, W.H. (1900). Nature In Downland. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- ^ Merrick, W.P. (1953). Folk Songs from Sussex. English Folk Dance and Song Society.

- ^ "Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra". Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ "Worthing Symphony Orchestra". Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ "Phun City Free Festival 1970". Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Great Escape festival". The Guardian. London. 28 March 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Scotland's Census 2011: Table KS209SCa" (PDF). scotlandcensus.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Brandon 2006

- ^ Brandon 2006

- ^ Jump up to: a b "East Sussex". The Keep. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Dimmock, Quinn & Hadfield 2013, p. 205

- ^ "The Joy of Sects: The profusion of minority faiths in a Sussex town hints at Britain's attitudes to religion". The Economist. 2 February 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Wallace, Danny (24 March 2018). "The profusion of minority faiths in a Sussex town hints at Britain's attitudes to religion". Metro.

- ^ Jordison, Sam (8 April 2016). "Tom Cruise will feel right at home in East Grinstead, Britain's strangest town". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1921". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1929". Nobel. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1974". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1996". Nobel. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw. "book extract from The Commanding Heights" (PDF). Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "How to kick-start a faltering economy the Keynes way". BBC. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Cohn, Steven Mark (2006). Reintroducing Macroeconomics: A Critical Approach. M.E. Sharpe. p. 111. ISBN 0-7656-1450-2.

- ^ Davis, William L, Bob Figgins, David Hedengren, and Daniel B. Klein. "Economic Professors' Favorite Economic Thinkers, Journals, and Blogs," Econ Journal Watch 8(2): 126–146, May 2011.[1]

- ^ "International Prize". Fondation Fyssen. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ McKie, Robin (5 February 2012), Piltdown Man: British archaeology's greatest hoax, London: The Observer, retrieved 16 November 2012

- ^ McCann 2004, p. xxxi

- ^ Tomlinson 2010, p. 489

- ^ McCann 2004, p. xxxi

- ^ Waghorn 1906, p. 3

- ^ "The 1st Cental County Ground". Sussex Cricket. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ Arundel Castle | UK Tourist Information | Plan Your Visit or Vacation at History-Tourist.com Archived 26 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Arundel Castle - England - Cricket Grounds - ESPNcricinfo". www.cricinfo.com.

- ^ "How Sussex's cricket league has become a world record-breaker". 1 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Coates 2010, p. 79

- ^ Gomme 1894, p. 219

- ^ Locke 2011, p. 203

- ^ Harvey, Adrian (2005). Football: The First Hundred Years: The Untold Story. Abingdon: Routledge.

- ^ "About the Sussex County Football League". Sussex County Football League. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "The DFS British Jumping Derby, Hickstead". Debretts. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Food Legends of the United Kingdom, Pulborough Eels, , Sussex". www.information-britain.co.uk.

- ^ "BBC Inside Out - The seven Sussex things that make the South heaven". www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Shopping - Francis Frith Archived 6 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sussex Pond Pudding Recipe - Historical Foods Archived 24 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sussex Plum Heavies Recipe - Historical Foods Archived 24 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sussex creators of Banoffee Pie serve last slice as Eastbourne restaurant closes". The Argus. 14 January 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Top 10 Original Dishes and Drinks". National Geographic. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "West Sussex breweries - Local Sussex beers and ales". www.westsussex.info.

- ^ "The English Apple Man, informing consumers about how the apples they buy are grown, harvested and marketed". theenglishappleman.com. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "Home". SeaCider. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "Ridgeview Wine Estate". Visit Sussex. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kirby, Terry (3 June 2012). "Is English wine really as good as anything France has to offer?". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Sussex Wines". Sussex Life Magazine. 22 December 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "Nyetimber Wines England". The Champagne Company. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Russell, Miles. "The Neolithic Flint Mines of Sussex: Britain's Earliest Monuments". University of Bournemouth. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Fishbourne Roman Palace & Gardens". Sussex Past, Sussex Archaeological Society. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Bignor Roman Villa, West Sussex". The Heritage Trail. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "The Long Man". Sussex Past, The Sussex Archaeological Society. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Sussex Depicted - Views and descriptions 1600-1800". Sussex Record Society. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Private patronage". South Downs National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "J.M.W. Turner, Vale of Ashburnham, a watercolour". British Museum. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Hughes, Kathryn (18 November 2011). "Edward Burra, transgressive painter of English countryside and dockside bars". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Two Exhibitions Celebrate the Sussex Work of Artist Eric Ravilious". Sussex Life Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Charleston - an Artists' Home and Garden". The Charleston Trust. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Surreal Friends". Pallant House Gallery. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Edward James and Salvador Dalí". West Dean College. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Farley Farm House - Introduction". Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Surrealism in Sussex" (PDF). Pallant House Gallery. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

Bibliography[]

- Armstrong, Jack Roy (1974). A History of Sussex. Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 9780850331851.

- Brandon, Peter, ed. (1978). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-240-7.

- Brandon, Peter (2006). Sussex. Robert Hale. ISBN 9780709069980.

- Coates, Richard (2010). The Traditional Dialect of Sussex. Pomegranate Press. ISBN 978-1-907242-09-0.

- Crouch, David (2000). The reign of King Stephen, 1135-1154. Longman. ISBN 9780582226586.

- Dimmock, Matthew; Quinn, Paul; Hadfield, Andrew (2013). Art, Literature and Religion in Early Modern Sussex. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1472405227.

- Gomme, Alice Bertha (1894). The traditional games of England, Scotland and Ireland : with tunes, singing rhymes and methods of playing according to the variants extant and recorded in different parts of the kingdom. London: David Nutt.

- Hamilton, J.S. (2010). The Plantagenets: History of a Dynasty. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441157126.

- Higham, Nicholas; Ryan, M.J. (2013). The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300125344.

- Kerridge, R. G. P.; Standing, M. R. (2000). Worthing, from Saxon settlement to seaside town. Worthing, West Sussex: Optimus Books. ISBN 9780953313242. OCLC 58876316.

- Kirby, D.P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. Routledge. ISBN 9780415242110.

- Laycock, Stuart (2012). Britannia: The Failed State: Tribal Conflicts and the End of Roman Britain. The History Press. ISBN 9780752487656.

- Locke, Tim (2011). Slow Sussex and the South Downs. Buckinghamshire: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841623436.

- Mate, Mavis (1992). "The economic and social roots of medieval popular rebellion: Sussex in 1450-1451". Economic History Review. 45 (4): 661–676. doi:10.2307/2597413. JSTOR 2597413.

- McCann, Tim (2004). Sussex Cricket in the Eighteenth Century. Sussex Record Society.

- Payton, Philip (2017). A History of Sussex. Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85936-232-7.

- Smith Futhey, John; Cope, Gilbert (1995). History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches. Chester County, Pennsylvania USA: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0788402067.

- Thomas, Amanda (2020). The Nonconformist Revolution: Religious dissent, innovation and rebellion. Pen and Sword History. ISBN 9781473875692.

- Tomlinson, Allan (2010). A Dictionary of Sports Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199213818.

- Venning, Timothy (2013). An Alternative History of Britain: The Anglo-Saxon Age. Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 9781781591253.

- Wacher, John, ed. (2020). Towns of Roman Britain. Routledge. ISBN 9781000117318.

- Waghorn, H. T. (1906). The Dawn of Cricket. Electric Press. ISBN 978-0-94-782117-3.

- Welch, M.G. (1992). Anglo-Saxon England. English Heritage. ISBN 978-0-7134-6566-2.

External links[]

- Map of Sussex on Wikishire

- Sussex

- Home counties

- Counties of England established in antiquity

- Counties of England disestablished in 1974