2019 United Kingdom general election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 650 seats in the House of Commons 326[n 1] seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Registered | 47,568,611 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 67.3% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

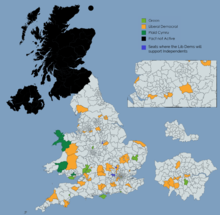

A map presenting the results of the election, by party of the MP elected from each constituency. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Composition of the House of Commons after the election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 2019 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday, 12 December 2019. It resulted in the Conservative Party receiving a landslide majority of 80 seats.[n 5] The Conservatives made a net gain of 48 seats and won 43.6% of the popular vote – the highest percentage for any party since 1979.[3]

Having failed to obtain a majority in the 2017 general election, the Conservative Party had faced prolonged parliamentary deadlock over Brexit while it governed in minority with the support of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). This situation led to the resignation of the Prime Minister, Theresa May, and the selection of Boris Johnson as Conservative leader and Prime Minister in July 2019. Johnson could not induce Parliament to approve a revised withdrawal agreement by the end of October, and chose to call for a snap election, which the House of Commons supported via the Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019.[4] Opinion polls up to polling day showed a firm lead for the Conservatives against the Labour Party throughout the campaign.[5]

The Conservatives won 365 seats; many of their gains were made in long-held Labour seats, dubbed the 'red wall', which had registered a strong 'Leave' vote in the 2016 EU referendum. Labour won 202 seats, its lowest number and proportion of seats since 1935.[6][7][8] The Scottish National Party (SNP) made a net gain of 13 seats and won 3.9% of the UK vote (translating to 45% of the popular vote in Scotland), resulting in 48 out of 59 seats won in Scotland.[9] The Liberal Democrats improved their vote share to 11.6% but won only 11 seats, a net loss of one since the last election.[10] The DUP won a plurality of seats in Northern Ireland. There, the SDLP and Alliance regained parliamentary representation as the DUP lost seats.

The election result gave Johnson a mandate to formally implement the UK’s departure from the European Union on 31 January 2020 and to repeal the European Communities Act 1972, thereby ending hopes of the Remain movement of overturning the result of the 2016 referendum. Labour's defeat led to Jeremy Corbyn conceding defeat and announcing his intention to resign, triggering a leadership election won by Keir Starmer.[8] For Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson, the loss of her constituency's seat compelled her to resign as well, triggering a leadership election.[11][10] The party's leader in Wales, Jane Dodds, was also unseated.[12] For the SNP leader, Nicola Sturgeon, her party's landslide victory in Scotland led to renewed calls for a second independence referendum.[9] In Northern Ireland, nationalist MPs outnumbered unionist ones for the first time, although the unionist popular vote remained higher (43.1%). Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow resigned the Speakership as a result of the election being called,[13][14] and the current Speaker, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, was subsequently elected.[15]

|

|

|

|

Background

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

|

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

|

|

In July 2016, Theresa May became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, having taken over from David Cameron (who had resigned in the wake of the 2016 Brexit referendum). Her party – the Conservative and Unionist Party – had governed the UK since the 2010 general election, initially in coalition with the Liberal Democrats and after the 2015 general election, alone with a small majority. In the 2017 general election, May lost her majority but was able to resume office as a result of a confidence and supply agreement with Northern Ireland's Democratic Unionist Party. In the face of opposition from the DUP and Conservative back-benchers, the second May ministry was unable to pass its Brexit withdrawal agreement by 29 March 2019, so some political commentators considered that an early United Kingdom general election was likely.[16] The opposition Labour Party called for a January 2019 vote of confidence in the May ministry, but the motion failed.[17] May resigned after her party's poor performance in the 2019 European Parliament election, during the first extension granted by the European Union for negotiations on the withdrawal agreement. Boris Johnson won the 2019 Conservative Party leadership election and became Prime Minister on 23 July 2019. Along with attempting to revise the withdrawal agreement arranged by his predecessor's negotiations, Johnson made three attempts to hold a snap election under the process defined in the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, which requires a two-thirds supermajority in order for an election to take place.[18][19][20][21]

All three attempts to call an election failed to gain support: Parliament insisted that Johnson "take a no-deal Brexit off the table first" and secure a negotiated Withdrawal Agreement, expressed in particular by its enactment against his will of the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 2) Act 2019 (often called the "Benn Act", after Labour MP Hilary Benn, who introduced the bill). After failing to pass a revised deal before the first extension's deadline of 31 October 2019, Johnson agreed to a second extension on negotiations with the EU and finally secured a revised Withdrawal Agreement. Parliament agreed to an election through a motion proposed by the Liberal Democrats and Scottish National Party on 28 October. The Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019 (EPGEA) was passed in the Commons by 438 votes to 20; an attempt to pass an amendment by opposition parties for the election to be held on 9 December failed by 315 votes to 295.[22][23] The House of Lords followed suit on 30 October,[24] with Royal Assent made the day after for the ratification of the EPGEA.[25]

Date of the election

The deadline for candidate nominations was 14 November 2019,[26] with political campaigning for four weeks until polling day on 12 December. On the day of the election, polling stations across the country were open from 7 am, and closed at 10 pm.[27] The date chosen for the 2019 general election made it the first to be held in December since 1923.[28][29]

Voting eligibility

Individuals eligible to vote had to be registered to vote by midnight on 26 November.[30] To be eligible to vote, individuals had to be[31][32] aged 18 or over; residing as a Commonwealth citizen at an address in the United Kingdom,[n 6] or a British citizen overseas who registered to vote in the last 15 years;[n 7][34][35] and not legally excluded (on grounds of detainment in prison, a mental hospital, or on the run from law enforcement)[36] or disqualified from voting.[37][38] Anyone who qualified as an anonymous elector had until midnight on 6 December to register.[n 8] Irish citizens living in the UK aged 18 and over were also allowed to vote.

Timetable

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Tuesday 29 October | Passage of the Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019 through the House of Commons |

| Wednesday 30 October | Passage of the Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019 through the House of Lords |

| Thursday 31 October | Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019 receives Royal Assent and comes into force immediately. The Act sets 12 December as the date for the next parliamentary general election. |

| Wednesday 6 November | Dissolution of Parliament and official start of the campaign. Beginning of purdah. Royal Proclamation issued, summoning a new Parliament and setting the date for its first meeting. |

| Thursday 7 November | Receipt of writ – legal documents declaring election issued |

| Friday 8 November | Notices of election begin to be given in constituencies |

| Thursday 14 November | Nominations of candidates close |

| Saturday 16 November | Lists of candidates are published for each constituency |

| Thursday 21 November | Deadline to register for a postal vote at 5pm (Northern Ireland)[41] |

| Tuesday 26 November | Deadline to register for a postal vote at 5pm (Great Britain)[41] and for registering to vote across the UK at 11:59pm[41] |

| Wednesday 4 December | Deadline to register for a proxy vote at 5pm. (Exemptions apply for emergencies.) |

| Thursday 12 December | Polling Day – polls open 7 am to 10 pm |

| Friday 13 December | Results announced for all the 650 constituencies. End of purdah |

| Tuesday 17 December | First meeting of the new Parliament of the United Kingdom, for the formal election of a Speaker of the Commons and the swearing-in of members, ahead of the State Opening of the new Parliament's first session.[42][43][44] |

| Thursday 19 December | State Opening of Parliament, Queen's Speech |

Contesting political parties and candidates

Most candidates are representatives of a political party, which must be registered with the Electoral Commission's Register. Those who do not belong to one must use the label "Independent" or none. In the 2019 election 3,415 candidates stood: 206 being independents, the rest representing one of 68 political parties.

Great Britain

| Party | Party leader(s) | Leader since | Leader's seat | 2017 election | Seats at dissolution |

Contested seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of votes |

Seats | |||||||

| Conservative Party | Boris Johnson | July 2019 | Uxbridge & South Ruislip | 42.4% | 317 | 298 | 635 seats in the United Kingdom[45] | |

| Labour Party | Jeremy Corbyn | September 2015 | Islington North | 40.0% | 262 | 244 | 631 seats in Great Britain | |

| Scottish National Party | Nicola Sturgeon | November 2014 | None[n 3] | 3.0% | 35 | 35 | 59 seats in Scotland | |

| Liberal Democrats | Jo Swinson | July 2019 | East Dunbartonshire | 7.4% | 12 | 21 | 611 seats in Great Britain | |

| Change UK | Anna Soubry | June 2019 | Broxtowe | New party | 5 | 3 seats in England | ||

| Plaid Cymru | Adam Price | September 2018 | None[n 9] | 0.5% | 4 | 4 | 36 seats in Wales | |

| Green Party of England and Wales | Jonathan Bartley | September 2016 | None[n 10] | 1.6% | 1 | 1 | 474 seats in England and Wales | |

| Siân Berry | September 2018 | |||||||

| Brexit Party | Nigel Farage | March 2019 | None[n 11] | New party | 0 | 276 seats in Great Britain | ||

As outlined in text above, Conservatives had been governing in coalition or on their own since 2010 and led by Boris Johnson since July 2019. Jeremy Corbyn had been Labour Party leader since 2015 and was the first Labour leader since Tony Blair to contest consecutive general elections, and the first since Neil Kinnock to do so after losing the first. One other party, the Liberal Democrats, contested seats across Great Britain. They were led by Tim Farron at the 2017 election, before he was replaced by Vince Cable. Cable was succeeded by Jo Swinson in July 2019.[46][47] The Brexit Party contested somewhat under half the seats. It was founded in early 2019 by Nigel Farage, former leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), and won the most votes at the May 2019 European Parliament elections. The Brexit Party had largely replaced UKIP in British politics, with UKIP (which gained 12.6% of the vote but just one MP at the 2015 election) losing almost all its support. UKIP stood in 42 seats in Great Britain and two seats in Northern Ireland.

The Green Party of England and Wales had been led by Jonathan Bartley and Siân Berry since 2018, with its counterpart the Scottish Green Party standing in Scottish seats. The two parties stood in a total of 495 seats. The third-largest party in seats won at the 2017 election was the Scottish National Party, led by Nicola Sturgeon since 2014, which stands only in Scotland where it won 35 out of 59 seats at the 2017 election. Similarly, Plaid Cymru, led by Adam Price, stands only in Wales where it held 4 of 40 seats.

Northern Ireland

While a number of UK parties organise in Northern Ireland (including the Labour Party, which does not field candidates) and others field candidates for election (most notably the Conservatives), the main Northern Ireland parties are different from those in the rest of the UK.

Some parties in Northern Ireland operate on an all-Ireland basis, including Sinn Féin and Aontú, who are abstentionist parties and do not take up any Commons seats to which they are elected. The only independent elected to Parliament in 2017, Sylvia Hermon, represented North Down but did not stand in 2019.

In the 2019 election, there were a total of 102 candidates in Northern Ireland.[48] The election result was particularly notable in Northern Ireland as the first Westminster election in which the number of Nationalists elected exceeded the number of Unionists.

| Party | Leader | Leader since | Leader's seat |

2017 election | Seats at dissolution |

Contested seats (out of 18) |

2019 election | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (in NI) |

Seats | % (in NI) |

Seats won | |||||||

| Democratic Unionist Party | Arlene Foster | December 2015 | None[n 12] | 36.0% | 10 | 10 | 17 seats | 30.6% | ||

| Sinn Féin | Mary Lou McDonald | February 2018 | None[n 13] | 29.4% | 7 | 7 | 15 seats | 22.8% | ||

| Social Democratic and Labour Party | Colum Eastwood | November 2015 | Foyle[n 14] | 11.7% | 0 | 0 | 15 seats | 14.9% | ||

| Ulster Unionist Party | Steve Aiken | November 2019 | None[n 15] | 10.3% | 0 | 0 | 16 seats | 11.7% | 0 | |

| Alliance Party | Naomi Long | October 2016 | None[n 16] | 7.9% | 0 | 0 | 18 seats | 16.8% | ||

| Independent | Sylvia Hermon | None[n 17] | 5.6% | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | |||

Electoral pacts and unilateral decisions

In England and Wales, the Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru, and the Green Party of England and Wales – parties sharing an anti-Brexit position – arranged a "Unite to Remain" pact. Labour declined to be involved. This agreement meant that in 60 constituencies only one of these parties, the one considered to have the best chance of winning, stood. This pact aimed to maximise the total number of anti-Brexit MPs returned under the first-past-the-post system by avoiding the spoiler effect.[49]

In addition, the Liberal Democrats did not run against Dominic Grieve (independent, formerly Conservative),[50] Gavin Shuker (independent, formerly Labour),[51] and Anna Soubry (The Independent Group for Change, formerly Conservative).[52][53]

The Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage had suggested the Brexit and Conservative parties could form an electoral pact to maximise the seats taken by Brexit-supporting MPs, but this was rejected by Johnson.[54] On 11 November, Farage announced that his party would not stand in any of the 317 seats won by the Conservatives at the last election. This was welcomed by the Conservative Party chairman James Cleverly, and he insisted there had been no contact between them and the Brexit Party over the plan.[55] Newsnight reported that conversations between members of the Brexit Party and the Conservative, pro-Brexit research support group European Research Group (ERG) led to this decision.[56] The Brexit Party reportedly requested that Johnson publicly state he would not extend the Brexit transition period beyond the planned end of December 2020 date and that he wished for a Canada-style free trade agreement with the EU. Johnson did make a statement covering these two issues, something which Farage referenced as key when announcing he was standing down some candidates. Both the Brexit Party and the Conservatives denied any deal was done between the two.[56][57][58] Farage later claimed that he, and eight other prominent Brexit Party figures, were offered a peerage two days before making the announcement to stand down 317 seats.[59] The claim lead to complaints to the Electoral Commission, CPS, and Metropolitan Police.

The Green Party also did not stand in two Conservative-held seats, Chingford and Woodford Green and Calder Valley, in favour of Labour.[60][61] The Green Party had also unsuccessfully attempted to form a progressive alliance with the Labour Party prior to Unite to Remain.[62] The Women's Equality Party stood aside in two seats in favour of the Liberal Democrats, after the Lib Dems adopted some of its policies.[63]

The DUP did not contest Fermanagh and South Tyrone and the UUP did not contest Belfast North so as not to split the unionist vote. Other parties stood down in selected seats so as not to split the anti-Brexit vote. The nationalist and anti-Brexit parties the SDLP and Sinn Féin agreed a pact whereby the SDLP did not stand in Belfast North (in favour of Sinn Féin), while Sinn Féin did not stand in Belfast South (in favour of SDLP); neither party stood in Belfast East or North Down[64] and advised their supporters to vote Alliance in those two constituencies. The Green Party in Northern Ireland did not stand in any of the four Belfast constituencies,[65] backing the SDLP in Belfast South, Sinn Féin in Belfast North and West, and Alliance in Belfast East and North Down;[66][67][68][69] the party only stood in the safe seats of East Antrim, Strangford and West Tyrone. Alliance did not stand down in any seats,[70] describing the plans as "sectarian".[71]

Marginal seats

At the 2017 election, more than one in eight seats was won by a margin of 5% or less of votes,[72] while almost one in four was won by 10% or less.[73] These seats were seen as crucial in deciding the election.[74]

2017–2019 MPs standing under a different political affiliation

The 2017–2019 Parliament was defined by a significant amount of political instability, and consequently; a large number of defections and switching between parties. This was due to issues such as disquiet over anti-semitism in the Labour Party, and divisions over Brexit in the Conservative Party. Eighteen MPs elected in 2017 contested the election for a different party or as an independent candidate; five stood for a different seat. All of these candidates failed to be re-elected.

| Outgoing MP | 2017 party | 2017 constituency | 2019 party | 2019 constituency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luciana Berger | Labour | Liverpool Wavertree | Liberal Democrats | Finchley and Golders Green | ||

| Frank Field | Labour | Birkenhead | Birkenhead Social Justice | Birkenhead | ||

| Mike Gapes | Labour | Ilford South | Change UK | Ilford South | ||

| David Gauke | Conservative | South West Hertfordshire | Independent | South West Hertfordshire | ||

| Roger Godsiff | Labour | Birmingham Hall Green | Independent | Birmingham Hall Green | ||

| Dominic Grieve | Conservative | Beaconsfield | Independent | Beaconsfield | ||

| Sam Gyimah | Conservative | East Surrey | Liberal Democrats | Kensington | ||

| Phillip Lee | Conservative | Bracknell | Liberal Democrats | Wokingham | ||

| Chris Leslie | Labour | Nottingham East | Change UK | Nottingham East | ||

| Ivan Lewis (withdrawn)[75] | Labour | Bury South | Independent | Bury South | ||

| Anne Milton | Conservative | Guildford | Independent | Guildford | ||

| Antoinette Sandbach | Conservative | Eddisbury | Liberal Democrats | Eddisbury | ||

| Gavin Shuker | Labour | Luton South | Independent | Luton South | ||

| Angela Smith | Labour | Penistone and Stocksbridge | Liberal Democrats | Altrincham and Sale West | ||

| Anna Soubry | Conservative | Broxtowe | Change UK | Broxtowe | ||

| Chuka Umunna | Labour | Streatham | Liberal Democrats | Cities of London and Westminster | ||

| Chris Williamson | Labour | Derby North | Independent | Derby North | ||

| Sarah Wollaston | Conservative | Totnes | Liberal Democrats | Totnes | ||

Withdrawn or disowned candidates

The following candidates withdrew from campaigning or had support from their party withdrawn after the close of nominations, and so they remained on the ballot paper in their constituency. Hanvey was elected;[76] the others were not.

| Candidate | Party | Constituency | Reason for withdrawal | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safia Ali | Labour | Falkirk | Alleged prior antisemitic posts on Facebook[77] | 28 November | |

| Amjad Bashir | Conservative | Leeds North East | Comments made in 2014 saying Jews were radicalised by visiting Israel[78][79] | 20 November[80][81] | |

| Sophie Cook | Independent | East Worthing and Shoreham | Reported experience of abuse and harassment[82] | 19 November | |

| Victor Farrell | Brexit Party | Glenrothes | Homophobic comments in 2017[83] | 18 November | |

| Neale Hanvey | SNP | Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath | Allegations of antisemitism (based on criticism of Israel and George Soros) in a 2016 Facebook post[84] | 28 November | |

| Ryan Houghton | Conservative | Aberdeen North | Allegations of Antisemitic, Islamophobic and homophobic tweets in 2012[85] | 19 November | |

| Ivan Lewis | Independent[a] | Bury South | Withdrew candidature and urged voters to vote Conservative[75] | 4 December | |

| Ben Mathis | Liberal Democrats | Hackney North and Stoke Newington | Tweets that included references to "hot young boys", "whiny bitches", and conjuring images of Katie Hopkins losing "several kilos of unpleasant fat…[with] an axe or a guillotine", before 2019[86] | 24 November | |

| Waheed Rafiq | Liberal Democrats | Birmingham, Hodge Hill | Antisemitic comments before 2015[87] | 20 November | |

| Flora Scarabello | Conservative | Glasgow Central | Islamophobic comment — recorded private words[88] | 27 November | |

- ^ A Labour MP until 2018

Campaign

Campaign background

| Party | Donations (£ millions) |

|---|---|

| Conservative | 37.7 |

| Liberal Democrats | 13.6 |

| Labour | 10.7 |

| Brexit | 7.2 |

| SNP | 0.2 |

The Conservative Party and Labour Party have been the two biggest political parties, and have supplied every Prime Minister since 1922. The Conservative Party have governed since the 2010 election, in coalition with the Liberal Democrats from 2010 to 2015. At the 2015 general election the Conservative Party committed to offering a referendum on whether the UK should leave the European Union and won a majority in that election. A referendum was held in June 2016, and the Leave campaign won by 51.9% to 48.1%. The UK initiated the withdrawal process in March 2017, and Prime Minister Theresa May triggered a snap general election in 2017, in order to demonstrate support for her planned negotiation of Brexit. The Conservative Party lost seats – they won a plurality of MPs, but not a majority. As a result, they formed a minority government, with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) as their confidence and supply partner. Neither May nor her successor Boris Johnson (winner of the 2019 Conservative Party leadership election)[90][91] was able to secure parliamentary support either for a deal on the terms of the UK's exit from the EU, or for exiting the EU without an agreed deal. Johnson later succeeded in bringing his Withdrawal Agreement to a second reading in Parliament, following another extension until January 2020.

During the lifespan of the 2017 parliament, twenty MPs resigned from their parties, most due to disputes with their party leaderships; some formed new parties and alliances. In February 2019, eight Labour and three Conservative MPs left their parties to sit together as The Independent Group.[92] Having undergone a split and two name changes, at dissolution this group numbered five MPs who sat as the registered party The Independent Group for Change under the leadership of Anna Soubry.[93][94] Two MPs sat in a group called The Independents (which at its peak had five members), one MP created the Birkenhead Social Justice Party, while a further 20 MPs who began as Labour or Conservative ended the Parliament as unaffiliated independents. Seven MPs, from both the Conservatives and Labour, joined the Liberal Democrats during the parliament, in combination with a by-election gain. The Lib Dems ultimately raised their number from 12 at the election to 20 at dissolution.[95]

One reason for the defections from the Labour Party was the ongoing row over antisemitism in the Labour Party. Labour entered the election campaign while under investigation by the Equality and Human Rights Commission.[96] The Jewish Labour Movement declared it would not generally campaign for Labour.[97] The Conservative Party was also criticised for not doing enough to tackle the alleged Islamophobia in the party.[98]

The Conservatives ended the previous parliamentary period with fewer seats than they had started with because of defections and also the expulsion of a number of MPs for going against the party line by voting to prevent a no-deal Brexit.[99] Of the 21 expelled, 10 were subsequently reinstated, while others continued as independents.[100]

Policy positions

Brexit

The major parties had a wide variety of stances on Brexit. The Conservative Party supported leaving under the terms of the withdrawal agreement as negotiated by Johnson (amending Theresa May's previous agreement), and this agreement formed a central part of the Conservative campaign.[101] The Brexit Party was in favour of a no-deal Brexit, with its leader Nigel Farage calling for Johnson to drop the deal.[102]

The Labour Party proposed a renegotiation of the withdrawal agreement (towards a closer post-withdrawal relationship with the EU) and would then put this forward as an option in a referendum alongside the option of remaining in the EU.[103] The Labour Party's campaigning stance in that referendum would be decided at a special conference.[104] In a Question Time special featuring four party leaders, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn said that he would stay neutral in the referendum campaign.[105]

The Liberal Democrats, Scottish National Party (SNP), Plaid Cymru, The Independent Group for Change, and the Green Party of England and Wales were all opposed to Brexit, and proposed that a further referendum be held with the option – for which they would campaign – to remain in the EU.[106] The Liberal Democrats originally pledged that if they formed a majority government (considered a highly unlikely outcome by observers),[107] they would revoke the Article 50 notification immediately and cancel Brexit.[106][108][109][110] Part-way through the campaign, the Liberal Democrats dropped the policy of revoking Article 50 after the party realised it was not going to win a majority in the election.[111]

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) was in favour of a withdrawal agreement in principle, but it opposed the deals negotiated by both May and Johnson, believing that they create too great a divide between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.[112][113] Sinn Féin, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP)[114] and Alliance all favoured remaining in the EU. The UUP did not see a second referendum as a necessary route to achieving this goal.[114]

The environment

The Labour Party promised what they described as a green industrial revolution. This included support for renewable energies and a promise to plant 2 billion trees by 2040. The party also promised to transition to electrify the UK's bus fleet by 2030.[115]

The Lib Dems also promised to put the environment at the heart of their agenda with a promise to plant 60 million trees a year. They also promised to significantly reduce carbon emissions by 2030 and hit zero carbon emissions by 2045. By 2030 they planned to generate 80% of the country's energy needs from renewable energies such as solar power and wind and retrofit 26 million homes with insulation by 2030. They also promised to build more environmentally friendly homes and to establish a new Department for the Climate Crisis.[citation needed]

The Conservatives pledged net zero emissions by 2050 with investment in clean energy solutions and green infrastructure to reduce carbon emissions and pollution. They also pledged to plant 30 million trees.[citation needed]

The Conservatives were judged the worst of the main parties on climate change by Friends of the Earth with a manifesto which mentioned it only ten times.[116]

Tax and spending commitments

In September 2019, the Conservative government performed a spending review, where they announced plans to increase public spending by £13.8 billion/year, and reaffirmed plans to spend another £33.9 billion/year on the National Health Service (NHS) by 2023. Chancellor Sajid Javid said the government had turned the page on 10 years of austerity.[117] During the election the parties produced manifestos that outlined spending in addition to those already planned.

The Conservative manifesto was described as having "little in the way of changes to tax" by the Institute for Fiscal Studies. The decision to keep the rate of corporation tax at 19%, and not reduce it to 17% as planned, is expected to raise £6 billion/year. The plan to increase the national insurance threshold for employees and self-employed to £9,500 will cost £2 billion/year.[118] They also committed to not raise rates of income tax, National Insurance or VAT.[119] There are increased spending commitments of £3 billion current spending and £8 billion investment spending. This would overall lead to the UK's debt as a percentage of GDP remaining stable (the IFS assesses that it would rise in the event of a no-deal Brexit).[120]

The Labour manifesto planned to raise an extra £78 billion/year from taxes over the course of the parliament, with sources including:[118]

- £24bn – raising the headline rate of corporation tax to 26%

- £6.3bn – tax multinationals' global profits according to UK share of global employment/assets/sales, not UK profits

- £4.0bn – abolish patent box & R&D tax credit for large companies

- £4.3bn – cutting unspecified corporation tax reliefs

- £9bn – financial transactions tax

- £14bn – dividends and capital gains

- £6bn – anti-avoidance

- £5bn – increases in income tax rates above £80,000/year

- £5bn – other

In addition, Labour was to obtain income from the Inclusive Ownership Fund, windfall tax on oil companies, and some smaller tax changes. There were increased spending commitments of £98 billion current spending and £55 billion investment spending. This would, overall, have led to the UK's debt as a percentage of GDP rising.[120] Labour's John McDonnell said borrowing would only be for investment and one-offs (e.g. compensating WASPI women, not shown above), and not for day-to-day spending.[121]

The Liberal Democrat manifesto plans to raise an extra £36 billion/year from taxes over the course of the parliament, with sources including:[118]

- £10bn – raising corporation tax to 20%

- £7bn – 1% point rise in all rates of income tax

- £5bn – abolish CGT allowance

- £5bn – air passenger duty on frequent flyers

- £6bn – anti-avoidance

- £3bn – other

There are increased commitments of £37 billion current spending and £26 billion investment spending, which would overall lead to the UK's debt as a percentage of GDP falling, partly due to improved economic conditions which would result from staying in the EU.[120]

Institute for Fiscal Studies analysis

The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS), an influential research body, released on 28 November its in-depth analysis of the manifestos of the three main national political parties. The analysis both provides a summary of the financial promises made by each party, and an inspection of the accuracy of claims around government income and expenditure.[122][123][124][125][118] The IFS reported that neither the Conservatives nor the Labour Party had published a "properly credible prospectus".[122]

Its analysis of the Conservative manifesto concluded there was "essentially nothing new in the manifesto", that there was "little in the way of changes to tax, spending, welfare or anything else", and that they had already promised increased spending for health and education whilst in government. The Labour manifesto was described as introducing "enormous economic and social change", and increasing the role of the state to be bigger than anything in the last 40 years.[126] The IFS highlighted a raft of changes in including free childcare, university, personal care and prescriptions, as well nationalisations, labour market regulations, increases in the minimum wage, and enforcing "effective ownership of 10% of large companies from current owners to a combination of employees and government". Labour's vision, the IFS said, "is of a state not so dissimilar to those seen in many other successful Western European economies" and presumed that the manifesto should be seen as "a long-term prospectus for change rather than a realistic deliverable plan for a five-year parliament".[126] They said the Liberal Democrat manifesto is not as radical as the Labour manifesto but was a "decisive move away from the policies of the past decade".[123][124][125][118]

The Conservative manifesto was criticised for a commitment not to raise rates of income tax, NICs or VAT as this put a significant constraint on reactions to events that might affect government finances. One such event could be the "die in a ditch" promise to terminate the Brexit transition period by the end of 2020, which risked harming the economy.[126] The IFS also stated that it is "highly likely" spending under a Conservative government would be higher than in that party's manifesto, partly due to a number of uncosted commitments.[122][123][124][125][118] Outside of commitments to the NHS, the proposals would leave public service spending 14% lower in 2023–2024 than it was in 2010–2011, which the IFS described as "no more austerity perhaps, but an awful lot of it baked in".[127]

The IFS stated it had "serious doubt" that tax rises proposed would raise the amount Labour suggested, and said that they would need to introduce more broad based tax increases. They assess that the public sector does not have the capacity to increase investment spending as Labour would want. The IFS assesses the claim that tax rises will only hit the top 5% of earners, as "certainly progressive", but "clearly not true", with those under that threshold impacted by changes to the marriage allowance, taxes on dividends or capital gains, and lower wages/higher prices that might be passed on from corporation tax changes. Some of Labour's proposals are described as "huge and complex undertakings", where significant care is required in implementation. The IFS is particularly critical of the policy to compensate the so-called "WASPI women", announced after the manifesto, which is a £58bn promise to women who are "relatively well off on average" and will result in public finances going off target. They said that Labour's manifesto would not increase UK public spending as a share of national income above Germany.[122][123][124][125][118] They found that Labour's plan to spend and invest would boost economic growth, but the impact of tax rises, government regulation, nationalisations and the inclusive ownership fund could reduce growth, meaning the overall impact of Labour's plan on growth is uncertain.[126][125]

The IFS described the Liberal Democrats' plans as a "radical" tax and spend package, and said that the proposals would require lower borrowing than Conservative or Labour plans. The report said they were the only party whose proposals would put debt "on a decisively downward path", praising their plan to put 1p on income tax to go to the NHS as "simple, progressive and would raise a secure level of revenue". The IFS also said plans to "virtually quintuple" current spending levels on universal free childcare amounted to "creating a whole new leg of the universal welfare state".[128][125]

The IFS said that the SNP's manifesto was not costed. Their proposals on spending increases and tax cuts would mean the UK government would have to borrow to cover day-to-day spending. They conclude that the SNP's plans for Scottish independence would likely require increased austerity.[129]

Other issues

The Conservative Party proposed increasing spending on the NHS, although not as much of an increase as Labour and Liberal Democrat proposals.[130] They also proposed increased funding for childcare and on the environment. They proposed more funding for care services and to work with other parties on reforming how care is delivered. They wish to maintain the "triple lock" on pensions. They proposed investing in local infrastructure, including building a new rail line between Leeds and Manchester.[119]

Labour proposed significantly increasing government spending to 45% of national output, which would be high compared to most of UK history, but is comparable with other European countries.[131] This was to pay for an increased NHS budget; stopping state pension age rises; introducing a National Care Service providing free personal care; move to a net-zero carbon economy by the 2030s; nationalising key industries; scrapping universal credit; free bus travel for under-25s; building 100,000 council houses per year; and other proposals.[132] Within this, the Labour Party proposed to take rail-operating companies, energy supply networks, Royal Mail, sewerage infrastructure, and England's private water companies back into public ownership. Labour proposed nationalising part of BT and to provide free broadband to everyone,[133] along with free education for six years during each person's adult life.[134][135] Over a decade, Labour planned to reduce the average full-time weekly working hours to 32, with resulting productivity increases facilitating no loss of pay.[136]

The Liberal Democrats' main priority was opposing Brexit. Other policies included increased spending on the NHS; free childcare for two-to-four-year-olds; recruiting 20,000 more teachers; generating 80% of electricity from renewable sources by 2030; freezing train fares; and legalising cannabis.[137]

The Brexit Party was also focused on Brexit. It opposed privatising the NHS. It sought to reduce immigration, cutting net migration to 50,000 per year; cutting VAT on domestic fuel; banning the exporting of waste; free broadband in deprived regions; scrapping the BBC licence fee; and abolishing inheritance tax, interest on student loans, and HS2. It also wanted to move to a US-style supreme court.[138]

The policies of the SNP included a second referendum on Scottish independence next year as well as one on Brexit, removing Trident, and devolution across issues such as employment law, drug policy, and migration.[139]

The Liberal Democrats, the Greens, the SNP and Labour all support a ban on fracking, whilst the Conservatives propose approving fracking on a case-by-case basis.[140][141]

Party positions in the event of a hung Parliament

The Conservatives and Labour both insisted they were on course for outright majorities, but smaller parties were quizzed about what they would do in the event of a hung Parliament. The Liberal Democrats said they would not actively support Johnson or Corbyn becoming Prime Minister, but that they could, if an alternative could not be achieved, abstain on votes allowing a minority government to form if there was support for a second referendum on Brexit.[142] The SNP ruled out either supporting the Conservatives or a coalition with Labour, but spoke about a looser form of support, such as a confidence and supply arrangement with the latter, if they supported a second referendum on Scottish independence.[143]

The DUP previously supported the Conservative government, but withdrew that support given their opposition to Johnson's proposed Brexit deal. It said it would never support Corbyn as prime minister, but could work with Labour if that party were led by someone else. Labour's position on a hung parliament was that it would do no deals with any other party, citing Corbyn to say "We are out here to win it"—although sources say it was prepared to adopt key policies proposed by the SNP and Lib Dems to woo them into supporting a minority government.[144][145] The UUP has also said they would never support Corbyn as Prime Minister, with their leader Steve Aiken saying he "can't really see" any situation in which they would support a Conservative government either. Their focus would be on remaining in the EU.[114]

Tactical voting

Under the first-past-the-post electoral system, voter turn-out (especially in marginal seats) has a crucial impact on the final election outcome[citation needed], so major political parties disproportionately focus on opinion poll trends and these constituencies. In the early stages of the campaign, there was considerable discussion of tactical voting (generally in the context of support or opposition to Brexit) and whether parties would stand in all seats or not.[146] There were various electoral pacts and unilateral decisions. The Brexit Party chose not to stand against sitting Conservative candidates, but stood in most other constituencies. The Brexit Party alleged that pressure was put on its candidates by the Conservatives to withdraw, including the offer of peerages, which would be illegal. This was denied by the Conservative Party.[147] Under the banner of Unite to Remain, the Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party of England and Wales agreed an electoral pact in some seats, but some commentators criticised the Liberal Democrats for not standing down in some Labour seats.[148]

A number of tactical voting websites were set up in an attempt to help voters choose the candidate in their constituency who would be best placed to beat the Conservative one.[149][150] The websites did not always give the same advice, which Michael Savage, political editor of centre-left The Guardian newspaper, said had the potential to confuse voters.[149] One of the websites - "GetVoting.org" - set up by Best for Britain – was accused of giving bogus advice in Labour/Conservative marginal seats.[151][152] The website, which had links to the Liberal Democrat party,[152] was criticised for advising pro-remain voters to back the Liberal Democrats when doing so risked pulling voters away from Labour candidates and enabling the Conservative candidate to gain most votes.[151][152] However, they changed their controversial recommendation in Kensington to Labour[citation needed], lining up with Tactical Vote (TacticalVote.co.uk) in this seat, who were the only anti-Brexit tactical voting site with no party affiliations[citation needed], while Gina Miller's Remain United and People's Vote kept their recommendation for the Liberal Democrats[citation needed]. This caused a lot of confusion around tactical voting,[149][153] as it was reported that the sites did not match one another's advice. Further into the election period, tactical voting websites that relied on MRP changed their recommendations on other seats because of new data.[154]

In the final weekend before voting, The Guardian cited a poll suggesting that the Conservative party held a 15% lead over Labour,[155] while on the same day, the Conservative-backing Daily Telegraph emphasised a poll indicating only an 8% lead.[156] Senior opposition politicians from Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the SNP launched a late-stage appeal to anti-Conservative voters to consider switching allegiance in the general election, amid signs that tactical voting in a relatively small number of marginal seats could deprive Johnson of a majority in parliament.[157]

Shortly before the election The Observer newspaper recommended remainers tactically vote for 50 Labour, Liberal Democrat, Scottish National and independent candidates across Great Britain;[158] of these, 13 triumphed, 9 of which were SNP gains in Scotland (in line with a broader trend of relative success for the party), along with four in England divided equally between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. The pollster responsible argued in the aftermath that the unpopularity of the Labour leadership limited the effectiveness of tactical voting.[159] Other research suggested it would have taken 78% of people voting tactically to prevent a Conservative majority completely, and would not have been possible to deliver a Labour majority.[160]

Canvassing and leafleting

Predictions of an overall Conservative majority were based on their targeting of primarily Labour-held, Brexit-backing seats in the Midlands and the north of England.[161] At the start of the election period, Labour-supporting organisation Momentum held what was described as "the largest mobilising call in UK history", involving more than 2,000 canvassers.[162] The organisation challenged Labour supporters to devote a week or more to campaigning full-time (by 4 December, 1,400 people had signed up). Momentum also developed an app called My Campaign Map that updated members about where they could be more effective, particularly in canvassing in marginal constituencies. Over one weekend during the campaign period, 700 Labour supporters campaigned in Iain Duncan Smith's constituency, Chingford and Woodford Green, which was regarded as a marginal, with a majority of 2,438 votes at the 2017 general election.[162]

The Liberal Democrats, likewise, were considered possible winners of a number of Conservative-held southern English constituencies, with a large swing that could even topple Dominic Raab in Esher and Walton.[163] At the beginning of the 2019 campaign, they had been accused of attempting to mislead voters by using selective polling data[164] and use of a quotation attributed to The Guardian newspaper rather than to their leader, Jo Swinson.[165] They were also accused of making campaign leaflets look like newspapers, although this practice had been used by all major British political parties for many years, including by Labour and the Conservatives during this election.[166]

The Liberal Democrats won a court case stopping the SNP from distributing a "potentially defamatory" leaflet in Swinson's constituency over false claims about funding she had received.[167]

Online campaigning

The use of social media advertising is seen as particularly useful to political parties as they can target people by gender, age, and location.[168] Labour is reported to have the most interactions, with The Times describing Labour's "aggressive, anti-establishment messages" as "beating clever Tory memes". In the first week of November, Labour is reported to have four of the five most "liked" tweets by political parties, many of the top interactions of Facebook posts, as well as being "dominant" on Instagram, where younger voters are particularly active.[169] Bloomberg reported that between 6 and 21 November, the views on Twitter/Facebook were 18.7m/31.0m for Labour, 10m/15.5m for the Conservatives, 2.9m/2.0m for the Brexit Party, and 0.4m/1.4m for the Liberal Democrats.[170]

Brexit was the most tweeted topic for the Conservative Party (~45% of tweets), the Liberal Democrats and the Brexit Party (~40% each). Labour focused on health (24.1%), the environment, and business, mentioning Brexit in less than 5 percent of its tweets.[171] Devolution was the topic most tweeted about by the SNP (29.8%) and Plaid Cymru (21.4%), and the environment was the top issue for the Green Party (45.9%) on Twitter. The Conservatives were unique in their focus on taxation (16.2%), and the Brexit Party on defence (14%).[171]

Prior to the campaign, the Conservatives contracted New Zealand marketing agency Topham Guerin, which has been credited with helping Australia's Liberal–National Coalition unexpectedly win the 2019 Australian federal election. The agency's social media approach is described as purposefully posting badly-designed social media material, which becomes viral and so is seen by a wider audience.[172][173] Some of the Conservative social media activity created headlines challenging whether it was deceptive.[174][175][176][177][178] This included editing a clip of Keir Starmer to appear he was unable to answer a question about Labour's Brexit policy.[175] In response to criticism over the doctored Starmer footage, Conservative Party chairman James Cleverly said the clip of Starmer was satire and "obviously edited".[175]

Veracity of statements by political parties

During the 19 November debate between Johnson and Corbyn hosted by ITV, the press office of the Conservative Campaign Headquarters (CCHQ) re-branded their Twitter account (@CCHQPress) as 'factcheckUK' (with "from CCHQ" in small text appearing underneath the logo in the account's banner image), which critics suggest could be mistaken for that of an independent fact-checking body, and published posts supporting the Conservative's position.[179][180][181][182][174][183] In defence, Conservative chairman Cleverly stated that "The Twitter handle of the CCHQ press office remained CCHQPress, so it's clear the nature of the site", and as "calling out when the Labour Party put what they know to be complete fabrications in the public domain".[174] In response to the re-branding on Twitter, the Electoral Commission, which does not have a role in regulating election campaign content, called on all campaigners to act "responsibly",[183][182][184] fact-checking body Full Fact criticised this behaviour as "inappropriate and misleading", and Twitter stated that it would take "decisive corrective action" if there were "further attempts to mislead people".[181][182][174][183][185][186]

First Draft News released an analysis of Facebook ads posted by political parties between 1 and 4 December. The analysis reports 88% of the 6,749 posts the Conservatives made had been "challenged" by fact checker Full Fact. 5,000 of these ads related to a "40 new hospitals" claim, of which Full Fact concluded only six had been costed, with the others only currently receiving money for planning (with building uncosted and due to occur after 2025). 4,000 featured inaccurate claims about the cost of Labour's spending plans to the tax payer. 500 related to a "50,000 more nurses" pledge, consisting of 31,500 new nurses, and convincing 18,500 nurses already in post to remain.[187][188][189] 16.5% of Liberal Democrats posts were highlighted, which related to claims they are the only party to beat Labour, the Conservatives or the SNP ‘in seats like yours’.[189][188] None of the posts made by Labour in the period were challenged, although posts made on 10 December claiming a "Labour government would save households thousands in bills" and the Conservative Party had "cut £8bn from social care" since 2010, were flagged as misleading.[188][189] According to the BBC, Labour supporters had been more likely to share unpaid-for electioneering posts, some of which included misleading claims.[190]

Television debates

| ← 2017 debates | 2019 |

|---|

ITV aired a head-to-head election debate between Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn on 19 November, hosted by Julie Etchingham.[191] ITV Cymru Wales aired a debate featuring representatives from the Conservatives, Labour, the Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru and the Brexit Party on 17 November, hosted by Adrian Masters.[192] Johnson cancelled his ITV interview with Etchingham, scheduled for 6 December, whilst the other major party leaders agreed to be interviewed.[193]

On the BBC, broadcaster Andrew Neil was due to separately interview party leaders in The Andrew Neil Interviews, and BBC Northern Ireland journalist Mark Carruthers to separately interview the five main Northern Irish political leaders.[194] The leaders of the SNP, Labour, Plaid Cymru, the Liberal Democrats and the Brexit Party were all interviewed by Neil and the leader of the Conservative Party was not,[195] leading Neil to release a challenge to Johnson to be interviewed.[196] The Conservatives dismissed Neil's challenge.[197] BBC Scotland, BBC Cymru Wales and BBC Northern Ireland also hosted a variety of regional debates.[198]

Channel 4 cancelled a debate scheduled for 24 November after Johnson would not agree to a head-to-head with Corbyn.[199] A few days later, the network hosted a leaders' debate focused on the climate. Johnson and Farage did not attend and were replaced on stage by ice sculptures with their party names written on them.[200] The Conservatives alleged this was part of a pattern of bias at the channel, complained to Ofcom that Channel 4 had breached due impartiality rules as a result of their refusal to allow Michael Gove to appear as a substitute,[201] and suggested that they might review the channel's broadcasting licence.[202] In response, the Conservatives, as well as the Brexit Party, did not send a representative to Channel 4's "Everything but Brexit" on 8 December,[203] and Conservative ministers were briefed not to appear on Channel 4 News.[204] Ofcom rejected the Conservatives' complaint on 3 December.[205]

Sky News was due to hold a three-way election debate on 28 November, inviting Johnson, Corbyn and Swinson.[206] Swinson confirmed she would attend the debate,[207] but it was later cancelled after agreements could not be made with Corbyn or Johnson.[208]

| 2019 United Kingdom general election debates in Great Britain | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Organisers | Venue | Region | Viewing figures (millions) |

P Present S Surrogate NI Not invited A Absent I Invited N No debate | ||||||||||||

| Con | Lab | SNP | LD | Plaid | GPEW | Brexit | |||||||||||

| 17 November[209] | ITV Cymru Wales | ITV Wales Studios, Cardiff[192] | Wales | 0.28 | S Davies |

S Thomas-Symonds |

NI | P Dodds |

S Saville Roberts |

NI | S Gill | ||||||

| 19 November[210] | ITV | dock10 studios, Salford[211] | UK | 7.34 | P Johnson |

P Corbyn |

NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | ||||||

| 22 November[212] | BBC (Question Time) |

Octagon Centre, Sheffield[213][212] | UK | 4.62 | P Johnson |

P Corbyn |

P Sturgeon |

P Swinson |

NI | NI | NI | ||||||

| 24 November (cancelled)[214][215] |

N Johnson |

N Corbyn |

NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | ||||||||||

| 26 November | BBC Wales (Wales Live) |

Pembrokeshire County Showground, Haverfordwest[216] |

Wales | TBA | S Davies |

S Griffith |

NI | P Dodds |

S Saville Roberts |

NI | S Wells | ||||||

| 28 November (cancelled)[208] |

N Johnson |

N Corbyn |

NI | N Swinson |

NI | NI | NI | ||||||||||

| 28 November[217] | Channel 4 (climate and nature) |

ITN Headquarters, London[218] | UK | TBA | A[n 18] Johnson |

P Corbyn |

P Sturgeon |

P Swinson |

P Price |

P Berry |

A Farage | ||||||

| 29 November[220] | BBC | Senedd, Cardiff[221] | UK | TBA | S Sunak |

S Long-Bailey |

P Sturgeon |

P Swinson |

P Price |

S Lucas |

S Tice | ||||||

| 1 December[222] | ITV | Dock10, Salford[223] | UK | TBA | S Sunak |

S Burgon |

P Sturgeon |

P Swinson |

P Price |

P Berry |

P Farage | ||||||

| 3 December[224] | BBC Wales | Wrexham Glyndŵr University, Wrexham | Wales | TBA | S Jones |

S Hanson |

NI | S John |

S ap Iorwerth |

NI | P Gill | ||||||

| 3 December[225] | STV | STV Pacific Quay, Glasgow | Scotland | TBA | P Carlaw |

P Leonard |

P Sturgeon |

P Rennie |

NI | NI | NI | ||||||

| 6 December | BBC | Maidstone Studios, Maidstone[226][227][228] | UK | 4.42 | P Johnson |

P Corbyn |

NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | ||||||

| 8 December[229][230] | Channel 4 (everything but Brexit) |

Leeds Beckett University, Leeds[231] | UK | TBA | A |

S Rayner |

S Whitford |

P Swinson |

P Price |

P Bartley |

A | ||||||

| 9 December[232] | BBC (Question Time Under 30) |

University of York, York[233] | UK | TBA | S Jenrick |

S Rayner |

S Yousaf |

P Swinson |

P Price |

P Bartley |

P Farage | ||||||

| 10 December[234] | BBC Scotland | BBC Pacific Quay, Glasgow | Scotland | TBA | P Carlaw |

P Leonard |

P Sturgeon |

P Rennie |

NI | NI | NI | ||||||

| 2019 United Kingdom general election debates in Northern Ireland | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Organisers | Venue | Viewing figures (millions) |

P Present S Surrogate NI Not invited A Absent I Invited N No debate | |||||||||||||

| DUP | SF | SDLP | UUP | APNI | |||||||||||||

| 8 December | UTV | Queen's Film Theatre, Belfast[235] | TBA | S Little-Pengelly |

P O'Neill |

P Eastwood |

P Aiken |

P Long | |||||||||

| 10 December[236] | BBC Northern Ireland | Broadcasting House, Belfast | TBA | S Donaldson |

P O'Neill |

P Eastwood |

P Aiken |

P Long | |||||||||

Campaign events

Before candidate nominations closed, several planned candidates for Labour and for the Conservatives withdrew, principally because of past social media activity. At least three Labour candidates and one Conservative candidate stood down, with two of the Labour candidates doing so following allegedly antisemitic remarks.[237] Two other Conservative candidates were suspended from the Conservative Party over antisemitic social media posts, but retained their candidacy for the party.[238][239][240][241] The Liberal Democrats removed one of its candidates over antisemitic social media posts, and defended two others.[242]

Several former Labour MPs critical of Corbyn endorsed the Conservatives.[243] Meanwhile, several former Conservative MPs, including former deputy prime minister Michael Heseltine, endorsed the Liberal Democrats and/or independent candidates.[244] A week before election day, former Conservative prime minister John Major warned the public against enabling a majority Conservative government, to avoid what he saw as the damage a Johnson-led government could do to the country through Brexit. Major encouraged voters to vote tactically and to back former Conservative candidates instead of those put forward by the Conservative Party.[245]

Floods hit parts of England from 7 to 18 November. Johnson was criticised for what some saw as his late response to the flooding[246][247] after he said they were not a national emergency.[248]

The Conservatives banned Daily Mirror reporters from Johnson's campaign bus.[249][250]

On 27 November, Labour announced it had obtained leaked government documents; they said these showed that the Conservatives were in trade negotiations with the US over the NHS. The Conservatives said Labour was peddling "conspiracy theories",[251] with Raab later suggesting this was evidence of Russian interference in the election.[252]

A terrorist stabbing attack occurred in London on 29 November; owing to this, the political parties suspended campaigning in London for a time.[253]

The 2019 NATO summit was held in Watford on 3–4 December 2019. It was attended by 29 heads of state and heads of government, including Donald Trump.[254]

On 6 December, Labour announced it had obtained leaked government documents which they said showed that Johnson had misled the public about the Conservatives' Brexit deal with the EU, specifically regarding customs checks between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which Johnson had said would not exist.[255]

Third-party campaigns

In February 2021, an investigation by openDemocracy found that third-party campaign groups "pushed anti-Labour attack ads to millions of voters ahead of the 2019 general election spent more than £700,000 without declaring any individual donation".[256] These included Capitalist Worker and Campaign Against Corbynism, both of which were set up less than three months before the election and quickly disappeared thereafter.[256] A further investigation, also reported by the Daily Mirror, found that a group run by Conservative activist Jennifer Powers had spent around £65,000 on dozens of advertisements attacking Corbyn and Labour on housing policy without declaring any donations.[257]

During the campaign, the i had reported that Powers was "a corporate lobbyist who is a former employee of the Conservative Party" and that her group had been one of "16 registrations completed since 5 November".[258] openDemocracy, meanwhile, reported on the new phenomenon of U.S.-style, Super PAC-esque groups in British elections in an article called "American dirty tricks are corroding British democracy".[259] Adam Ramsay, who wrote the article, contacted Powers and got her to admit to being an associate at the trade consultancy firm Competere, which was set up by lobbyist Shanker Singham, who works for the neoliberal think tank, the Institute for Economic Affairs.[259] Powers' group, "Right to Rent, Right to Buy, Right to Own", made claims that Labour wanted to "attack property rights in the UK" and "your mortgage will be harder to pay under Labour".[257][260]

openDemocracy also reported that, during the election campaign, the pro-Labour group Momentum spent more than £500,000, the European Movement for the United Kingdom spent almost £300,000 and the anti-Brexit groups Led By Donkeys and Best for Britain spent £458,237 and more than one million pounds respectively.[256]

Following these reports, former Liberal Democrat MP Tom Brake, who lost his seat in the election and is now director of the pressure group Unlock Democracy, wrote to the Electoral Commission, urging them to investigate.[257] These calls were echoed by Labour MP and former Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell, who insisted that "a serious and in-depth inquiry into third-party campaigning" was needed.[261]

Religious groups' opinions on the parties

Ethnic minority and religious leaders and organisations made statements about the general election, with some people within the religious groups being keen to express that no one person or organisation represents the views of all the members of the faith.[262][263][264][265] Leaders of the Church of England stated people had a "democratic duty to vote", that they should "leave their echo chambers", and "issues need to be debated respectfully, and without resorting to personal abuse".[266]

Antisemitism in the Labour Party was persistently covered in the media in the lead up to the election. In his leader's interview with Jeremy Corbyn, Andrew Neil dedicated the first third of the 30-minute programme entirely for discussion of Labour's relationship with the Jewish community.[267] This interview drew attention as Corbyn refused to apologise for antisemitism in the Labour Party, despite having done so on previous occasions.[268] The UK's Chief Rabbi, Ephraim Mirvis, made an unprecedented intervention in politics, warning that antisemitism was a "poison sanctioned from the top" of the Labour Party, and saying that British Jews were gripped by anxiety about the prospect of a Corbyn-led government.[269] Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Muslim Council of Britain and the Hindu Council UK supported Rabbi Mirvis's intervention, if not entirely endorsing it.[270][271] Labour's only Jewish affiliate, the Jewish Labour Movement, said they would not be actively campaigning for Labour except for exceptional candidates.[272]

The Muslim Council of Britain spokesman stated Islamophobia "is particularly acute in the Conservative Party" and that Conservatives treat it "with denial, dismissal and deceit".[273] In addition they released a 72-page document, outlining what they assess are the key issues from a British Muslim perspective. The MCB specifically criticises those who "seek to stigmatise and undermine Muslims"; for example, by implying that Pakistanis ("often used as a proxy for Muslims") "vote en bloc as directed by Imams".[274] The Sunday Mirror had also claimed that many of the candidates campaigning for the Brexit Party were Islamophobic.[275]

The Times of India reported that supporters of Narendra Modi's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) were actively campaigning for the Tories in 48 marginal seats,[276] and the Today programme reported that it had seen WhatsApp messages sent to Hindus across the country urging them to vote Conservative.[277][278] Some British Indians spoke out against what they saw as the BJP's meddling in the UK election.[265] The Hindu Council UK has been strongly critical of Labour, going as far as to say that Labour is "anti-Hindu"[279] and objected to the party's condemnation of the Indian government's actions in the disputed territory of Kashmir.[278] The perceived "parachuting" of the Labour candidate for Leicester East, a constituency with many British Indians disappointed many with Indian heritage;[280] specifically, no candidates of Indian descent were interviewed. The party selected (or re-selected) one candidate of Indian descent among its 39 safest seats.[281]

Endorsements

Newspapers, organisations and individuals had endorsed parties or individual candidates for the election.

Media coverage

Party representation

This section is missing information about coverage outside the first week of the campaign. (June 2021) |

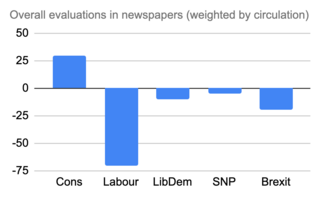

The Conservatives were the only party with an overall positive coverage, while Labour had the most negative coverage.

According to Loughborough University's Centre for Research in Communication and Culture (CRCC), media coverage of the first week of the campaign was dominated by the Conservatives and Labour, with the leaders of both parties being the most represented campaigners (Johnson with 20.8%; Corbyn with 18.8%).[282][283] Due to this, the election coverage has been characterised as increasingly 'presidential' as smaller parties have been marginalised.[283]

In television coverage, Boris Johnson had a particularly high-profile (30.4% against Corbyn's 22.6%). Labour (32%) and the Conservative Party (33%) received about a third of TV coverage each.

In newspapers, Labour received two-fifths (40%) of the coverage and the Conservatives 35%. Spokespeople from both parties were quoted near equally, with Conservative sources being the most prominent in both press and TV coverage in terms of frequency of appearance. Sajid Javid and John McDonnell featured prominently during the first week because the economy was a top story for the media. McDonnell had more coverage than Javid on both TV and in print.[282]

A large proportion of the newspaper coverage of Labour was negative.[284] James Hanning, writing in the British Journalism Review, said that, when reporting and commenting on Boris Johnson, Conservative supporting newspapers made little mention of "a track record that would have sunk any other politician".[204] In the Loughborough analysis, during the first week of the campaign, for example, the Conservatives had a positive press coverage score of +29.7, making them the only party to receive a positive overall presentation in the press. Labour, meanwhile, had a negative score of -70, followed by the Brexit Party on -19.7 and the Liberal Democrats on -10.[282][285] Over the whole campaign, press hostility towards Labour had doubled compared with during the 2017 election, and negative coverage of the Conservatives halved.[171]

The Liberal Democrats were the party with the most TV coverage in the first week after Labour and the Conservatives, with an eighth of all reporting (13%). In newspapers they received less coverage than the Brexit Party, whose leader Nigel Farage received nearly as much coverage (12.3%) as Johnson and Corbyn (17.4% each). Most of this coverage regarded the Brexit Party's proposed electoral pact with the Conservatives.[282] The Brexit Party (7%) and the SNP (5%) were fourth and fifth in terms of TV coverage, respectively.[282]

Dominant issues

As during the 2017 election, the electoral process was the most covered media topic for this election (31% of all coverage).[171] Brexit was the most prominent policy issue on both TV (18%) and in the press (11%), followed by the economy and health (8% and 7% of all coverage respectively).[171] However, there was little focused analysis on what the implementation of Brexit policies might mean, in contrast the analysis of other manifesto commitments on the economy, for example.[171] How Brexit might affect the union between England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland received some prominence on TV but little coverage in the press.[171] According to the Centre for Research in Communication and Culture, "Standards/scandals" received as much coverage overall as health.[171]

Gender balance

Of the 20 most prominent spokespeople in media coverage of the first week of the election period, five were women, with SNP leader and Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, in seventh place, the most featured.[282] Women (including, e.g., citizens, experts, pollsters, businesspeople, trade union representatives, etc.) featured in 23.9% of coverage and men in 76.1%. Men spoke three times as much as women in TV coverage, and five times as much in newspaper coverage.[282][286]

Members of Parliament not standing for re-election

74 MPs who held seats at the end of the Parliament did not stand for re-election.[287][288]

Opinion polling

| Opinion polling for UK general elections |

|---|

| 2010 election |

| Opinion polls |

| 2015 election |

| Opinion polls • Leadership approval |

| 2017 election |

| Opinion polls |

| 2019 election |

| Opinion polls • Leadership approval |

| Next election |

| Opinion polls • Leadership approval |

The chart below depicts the results of opinion polls, mostly only of voters in Great Britain, conducted from the 2017 United Kingdom general election until the election. The line plotted is the average of the last 15 polls and the larger circles at the end represent the actual results of the election. The graph shows that the Conservatives and Labour polled to similar levels from mid 2017 to mid 2019. Following Johnson's election in July, the Conservatives established a clear lead over Labour and simultaneously, support for the Brexit Party declined from its peak in summer 2019. The Spreadex columns below cover bets on the number of seats each party will win with the midpoint between asking and selling price.

Predictions three weeks before the vote

The first-past-the-post system used in UK general elections means that the number of seats won is not directly related to vote share. Thus, several approaches are used to convert polling data and other information into seat predictions. The table below lists some of the predictions.

| Parties | Electoral Calculus[289] as of 20 November 2019 |

Election Maps UK[290] as of 17 November 2019 |

Elections Etc.[291] as of 20 November 2019 |

BritainElects[292] as of 20 November 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 365

|

346

|

354

|

346

| |

| Labour Party | 201 | 211 | 206 | 211 | |

| SNP | 46 | 51 | 45 | 51 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 15 | 18 | 25 | 24 | |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Green Party | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Brexit Party | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Others | 18[293] | 19[294] | 18 | 18 | |

| Overall result (probability) | Conservative 80 seat majority |

Conservative 42 seat majority |

Conservative 58 seat majority |

Conservative 42 seat majority | |

Predictions two weeks before the vote

| Parties | Electoral Calculus[289][295] as of 27 November 2019 |

Election Maps UK[296] as of 28 November 2019 |

Elections Etc.[297] as of 27 November 2019 |

YouGov[298][299] as of 27 November 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 342

|

338

|

353

|

359

| |

| Labour Party | 224 | 226 | 208 | 211 | |

| SNP | 41 | 45 | 44 | 43 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 19 | 14 | 23 | 13 | |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |

| Green Party | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Brexit Party | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Others | 19[300] | 19[301] | 19 | 19 | |

| Overall result | Conservative 34 seat majority |

Conservative 26 seat majority |

Conservative 56 seat majority |

Conservative 68 seat majority | |

Note: Elections etc does not add up to 650 seats due to rounding; the Speaker is shown under "Others" and not "Labour"; majority figures assume all elected members take up their seats.

Predictions one week before the vote

Prediction based upon polls:

| Parties | Electoral Calculus[289] as of 8 December 2019 |

Election Maps UK[302] as of 6 December 2019 |

Elections Etc.[303] as of 5 December 2019 |

UK-Elect[304] as of 8 December 2019 |

Graphnile[305] as of 11 December 2019 |

Spreadex[306]

as of 5 December 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 348

|

345

|

346

|

354

|

352

|

341

| |

| Labour Party | 225 | 224 | 218 | 212 | 221 | 220 | |

| SNP | 41 | 43 | 45 | 43 | 52 | 44.5 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 13 | 14 | 19 | 17 | N/A | 21 | |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | N/A | 4 | |

| Green Party | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1.5 | |

| Brexit Party | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1.75 | |

| Others | 19[307] | 19[308] | 19[309] | 19[310] | 25 | N/A | |

| Overall result | Conservative 46 seat majority |

Conservative 40 seat majority |

Conservative 42 seat majority |

Conservative 58 seat majority |

Conservative 56 seat majority |

Conservative 32 seat majority | |

Note: Elections etc does not add up to 650 seats due to rounding; the Speaker is shown under "Others" and not "Labour"; majority figures assume all elected members take up their seats.

Prediction based upon betting odds (assuming the favourite wins in each constituency):

| Parties | Oddschecker[311] | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 351

| |

| Labour Party | 210 | |

| SNP | 44 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 18 | |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | |

| Green Party | 1 | |

| Brexit Party | 0 | |

| Others | 19[312] | |

| Too close to call | 3 | |

| Overall result | Conservative 52 seat majority | |

Note: The Speaker is shown under "Others" and not "Labour"; majority figures assume all elected members take up their seats.

Final predictions

| Parties | YouGov[313] as of 10 December 2019 |

Electoral Calculus[314] as of 12 December 2019 |

Election Maps UK[315] as of 12 December 2019 |

Elections Etc.[316] as of 12 December 2019 |

UK-Elect[317] as of 11 December 2019 |

Spreadex[318]

as of 11 December 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 339

|

351

|

344

|

341

|

348

|

340

| |

| Labour Party | 231 | 224 | 223 | 224 | 217 | 222 | |

| SNP | 41 | 41 | 45 | 43 | 44 | 43 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 15 | 13 | 14 | 19 | 17 | 21 | |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Green Party | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Brexit Party | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Others | 19 | 18[319] | 18[320] | 19 | 19[321] | N/A | |

| Overall result | Conservative 28 seat majority |

Conservative 52 seat majority |

Conservative 38 seat majority |

Conservative 32 seat majority |

Conservative 46 seat majority |

Conservative 30 seat majority | |

Exit poll

An exit poll conducted by Ipsos MORI for the BBC, ITV and Sky News, was published at the end of voting at 10 pm, predicting the number of seats for each party.[322][323]

| Parties | Seats | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Party | 368 | ||

| Labour Party | 191 | ||

| Scottish National Party | 55 | ||

| Liberal Democrats | 13 | ||

| Plaid Cymru | 3 | ||

| Green Party | 1 | ||

| Brexit Party | 0 | New party | |

| Others | 19 | ||

| Conservative 86 seat majority | |||

Results

The Conservative Party won, securing 365 seats out of 650, giving them an overall majority of 80 seats in the House of Commons. They gained seats in several Labour Party strongholds in Northern England that were held by the party for decades, which had formed the so-called 'red wall', such as the constituency of Bishop Auckland, which elected a Conservative MP for the first time in its 134-year history. In the worst result for the party in 84 years,[324] Labour won 202 seats, a loss of 60 compared to the previous election.[325][326] This marked a fourth consecutive general election defeat. The Liberal Democrats won 11 seats, down 1, despite significantly increasing their share of the popular vote. Leader Jo Swinson lost her seat to Amy Callaghan of the SNP by 150 votes, and was thus disqualified from continuing as leader of the party. Former coalition cabinet minister and MP for Kingston and Surbiton Ed Davey was the winner of the leadership election which then took place in August 2020.