1927 Chicago mayoral election

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

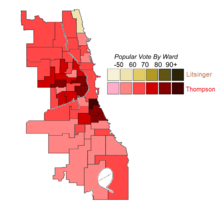

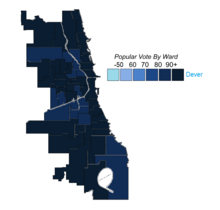

Results by ward | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Illinois |

|---|

|

The 1927 Chicago mayoral election was held on April 5. Democratic incumbent William Emmett Dever was defeated by Republican candidate William Hale Thompson, who had served as mayor from 1915 to 1923. Former health commissioner John Dill Robertson, who had been allied with the ex-mayor, broke with Thompson to run on his own and received more than five percent of the vote. It remains as of 2019 the last Chicago mayoral election not won by a Democrat.

Dever enforced Prohibition despite being personally opposed to it. This led to increased bootlegging and violence in the city and reduced citizen support. Thompson and Robertson seized the opportunity and entered the race. Thompson promised to end the enforcement of Prohibition and accused the United Kingdom of trying to retake control of the United States, while Robertson promised to quash the crime wave. Thompson bitterly attacked his campaign opponents and it was public knowledge that he was supported and funded by Al Capone. Dever's supporters pushed back against Thompson's rhetoric, asserting that Dever had the sensible policies and the "decency" appropriate for the city. Thompson's victory damaged Chicago's national reputation.

Background[]

Democrat William Emmett Dever had been elected mayor of Chicago in 1923 and initially focused on reform.[1] Observing the corruption of city government caused by bootleggers, he resolved to crack down on the illegal liquor trade and strengthen enforcement of Prohibition.[2] He was himself opposed to Prohibition, but felt that disregard for one law could lead to disregard for others.[2] His crackdown on Prohibition was initially effective and led to him being considered a potential dark horse candidate for President of the United States.[3] Nevertheless, the limited supply of alcohol led to bootleggers competing with one another, increasing violence in the city,[3] lowering Chicagoans' approval of Dever's performance.[4] Aware of the effects of Prohibition enforcement on his mayoralty, Dever was reluctant to run for a second term in 1927, a feeling strengthened by poor health and lucrative job offers in the private sector.[5] George E. Brennan, chief of the Democratic party, felt that Dever was the Democrats' strongest candidate against Thompson,[6] and he and businessman Julius Rosenwald convinced Dever to run for reelection.[7]

Republican William Hale "Big Bill"[8] Thompson, who was mayor for two terms from 1915 to 1923, took advantage of the situation and ran for a third term, promising to end the enforcement of Prohibition.[9] Having declined a bid for reelection in 1923, he had managed to stay in the public eye by constructing a yawl named the Big Bill with his head as the figurehead and spending $25,000[a] to take it on an expedition to Borneo to find a tree-climbing fish, all ostensibly as a publicity stunt for the Illinois Waterway.[10] He was immensely popular with the city's African-American community,[11] having served as alderman of the 2nd ward, home of Chicago's largest black population,[12] from 1900 to 1902.[13] He also had enemies from his previous tenure, including the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Daily News,[14] and had started to wear out his welcome with former allies such as party boss Frederick Lundin.[15]

John Dill Robertson, also known as "J.D.", "Doctor Dill", and "Dill Pickle", who had previously been the city's health commissioner from 1915 to 1922[16] the President of the Chicago Board of Education after that,[17] and an ally of Thompson,[12] ran against Thompson in the Republican primary supported by Lundin.[18] Serving at the time as President of the West Parks Board,[b][20] he promised to enforce Prohibition while it was still on the books and to smash organized crime in thirty days if elected, comparing gunmen gangs to boils and the bootleg industry to an appendix.[18] Lundin later had Robertson withdraw from the Republican primary in order to campaign for candidate Edward R. Litsinger, and Robertson agreed not to run as an independent in the general election if Litsinger won the primary.[21] Early in the campaign Thompson debated with live rats representing Robertson and Lundin.[22][23]

Primary elections[]

Primary elections took place on February 22,[24][25] along with primary elections for City Clerk and City Treasurer and the first round of aldermanic elections.[26]

Democratic primary[]

Dever faced no genuine opposition from within his party.[27] Attorney Martin Walsh of the 27th ward filed on February 2, claiming to have the backing of "the old municipal ownership leaders" and joining the race "to give Mayor Dever a little exercise."[28] Barratt O'Hara, former Lieutenant Governor of Illinois, withdrew from the race on February 11, claiming that running against Dever was hopeless and that Democrats opposed to Dever would vote in the Republican primary for Thompson.[29]

Although he overwhelmingly defeated his token opponent, winning all the wards and securing the citywide vote by more than 10 to 1,[24][26] Dever's vote total in the Democratic primary was less than the margin of victory Thompson had secured in the Republican primary.[9][25] Dever's camp argued that this was not a bad omen but rather that, due to the lack of a competitive race in the Democratic primary, many of Dever's supporters either did not participate in the primaries or voted instead for Thompson in the Republican primary to try and nominate the weaker prospective opponent.[25] Dever anticipated that he would still be able to win reelection with more than 600,000 votes in the general election.[25]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | William Emmett Dever (incumbent) | 149,422 | 91.85 | |

| Democratic | Martin Walsh | 13,260 | 8.15 | |

| Turnout | 162,682 | 100.00 | ||

Republican primary[]

Edward R. Litsinger, who was chairman of the Cook County Board of Review and backed by reform-minded U.S. Senator Charles S. Deneen and Edward J. Brundage,[20][30] (the latter of whom had split from his political ally Robert E. Crowe by supporting Litsinger[31]) announced his platform on January 9.[30] He promised to compel the City Council to adopt an ordinance that would end the Chicago Traction Wars and mandate a board of control and the consolidation of all transportation lines,[c] to construct subways, to form a police investigation into the rampant crime, to look at causes of recent tax increases and investigate potential ways to reverse them, and to clean up streets and alleys.[30]

Robertson initially planned to run in the primary before dropping out in favor of Litsinger per his agreement with Lundin, mounting an independent bid upon Litsinger's primary loss.[20][34] Former policeman Eugene McCaffrey filed for candidacy on February 2 and attracted suspicion as many of the names on his petition sheets appeared to have been written in the same handwriting.[28] He was allowed on the ballot and received more than 1,500 votes.[24]

The Republican primary was marked by intense vitriol between the candidates.[35] Thompson accused Robertson of messy eating, stating that "[With] eggs in his whiskers, soup on his vest, you'd think the doc got his education driving a garbage wagon."[35] Robertson retaliated, accusing Thompson of corruption.[35] Litsinger reiterated such accusations against Thompson and further accused Thompson of conspiring to get 50,000 Democratic votes.[35] Both candidates asserted that they were guaranteed victory and accused the other of conspiring to steal the primary.[35]

In an open letter, Thompson charged that Edward Brundage and Fred Lundin were suburbanites and were guilty of betraying their city roots.[34] He also alleged that Litsinger, who had come from Back of the Yards, had abandoned his roots, writing "You moved to the Gold Coast. Are you thinking of joining the high brows of Lake Forest and becoming a resident of Lake County too?"[34]

Thompson won by a surprisingly large margin;[36] to many, his victory itself was a surprise.[34] He carried 49 of the city's 50 wards.[36] After Thompson's victory both partisans of Robertson and Democratic leaders claimed that Democratic voters for Thompson had propelled him to the Republican nomination, with the Democrats claiming that they did so in order to give Dever a weaker opponent in the general election.[27] With Thompson's primary victory Robertson launched his independent campaign on February 23.[37]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | William Hale Thompson | 342,279 | 67.62 | |

| Republican | Edward R. Litsinger | 162,240 | 32.05 | |

| Republican | Eugene McCaffrey | 1,633 | 0.32 | |

| Turnout | 506,152 | 100.00 | ||

General election[]

The general election was held on April 5, along with general elections for City Clerk and City Treasurer[38] and aldermanic runoffs.[39]

Campaign[]

Thompson accused Dever of treason.[41] Using the slogan "America First",[41][42] he alleged that school superintendent William McAndrew was a British agent sent by King George as part of a grand conspiracy to manipulate the minds of American children and set the groundwork for the United Kingdom to repossess the United States; he accused the "left-handed Irishman" Dever of being part of the plot.[41][43] Thompson based these claims on McAndrew being critical of such artworks as Archibald Willard's The Spirit of '76 and allowing the use in schools of textbooks which Thompson believed were unpatriotic.[41] Thompson declared that his America First slate would elect so many of its candidates that "the king of England will find out for the first time he is damned unpopular",[8] and implied that he might have Dever sent to jail.[8] He described Dever as "very weak, no courage, no manhood, doesn't know how to fight".[8] He promised to reform the police department by ending enforcement of prohibition.[44] He also criticized the League of Nations and the World Court.[45][46] Thompson also supported ending the metering of municipal water.[46]

Democratic chief Brennan said that "All the hoodlums are for Thompson", which Thompson used to convince his supporters that the Democrats were elitist and looked down upon them.[44] Campaigning for German votes, Thompson stated:

They called me pro-German during the war because I kept my oath to protect the people. If you make a mistake and vote for some one who doesn't care for you or his oath to God, you'll have to pay the penalty. If I'm elected mayor, I'll build the largest town hall in the world where your German choruses of 25,000 voices can sing as they never have before.[44]

Dever refused to engage in Thompson's style of rhetoric.[47][48] He instead promised to engage in a debate of substantive issues, partaking only in a "decent, friendly discussion without malice or sensationalism".[26] He responded to Thompson's accusations by declaring them "blarney" which he had no intention of dignifying,[47] and noting that Thompson's comments on international affairs were irrelevant to the duties and powers of the mayoralty.[45] He ran on the slogans "Dever for Decency" and "The best mayor Chicago ever had",[44] the former also used by The Independent Republicans for Dever Committee.[49] He attempted, particularly early in the race, to tout parts of his record such as his construction of Wacker Drive and 51 new schools, as well as a pure milk ordinance he had helped pass.[25] He promised to continue his construction program, including building a long-anticipated State Street subway and widening LaSalle Street.[e][25] He did concede that "no superman can be found to eliminate crime".[25]

Supporters of both Thompson and Dever resorted to bigotry.[47] Some Republicans used anti-Catholic rhetoric against Dever.[47] Some Democrats attempted to take advantage of Thompson's positive relation with the city's African-American community and divide voters racially,[51] claiming that Thompson's election would lead to "Negro supremacy".[47] Palm cards were circulated with an image of Thompson kissing a black boy and with the reverse side reading "Thompson—Me Africa First".[52] Some Democrats hired black people to canvass white neighborhoods for Thompson in an effort to scare white voters.[52] They also attempted to lure black Thompson voters downtown, where they did not often go, with a fake rally outside of Thompson's campaign headquarters.[52] Supporters of each candidate accused the other's supporters of plotting to use underhanded tactics to steal the election.[47]

Robertson continued his platform of quashing crime, promising to "find another Theodore Roosevelt" as police chief and smash organized crime within thirty days.[53] Also running was George Koop,[38] who had previously been the Socialist candidate for mayor in 1907.[54]

Endorsements[]

Deneen backed Thompson after his primary defeat.[34] The Chicago Federation of Labor endorsed Thompson.[46] Margaret Haley, president of the Chicago Federation of Teachers, personally endorsed him as well.[46] The Cook County Wage-Earners' League ran an advertisement for Thompson in the Chicago Tribune, in which it claimed that 95 percent of the trades unions in Chicago endorsed him.[55] Thompson was backed by two Hearst-owned newspapers, as well as the African-American Daily Defender and L'Italia, the city's second-best selling Italian newspaper.[49] Martin Walsh, who had run against Dever in the Democratic Primary, served as a stump speaker for Thompson.[56] Thompson received the endorsement of Al Capone after promising lax enforcement of Prohibition.[57] It was public knowledge that Capone was supporting Thompson's campaign effort,[47] collecting campaign contributions from those who sold his beer.[57] Capone donated between $100,000[f][45] and $500,000[g][58] to Thompson's campaign. Other crime figures backing Thompson included Jack Zuta,[58] who gave $50,000[h] to his campaign,[59] Timothy D. Murphy, and Vincent Drucci.[58]

Dever was endorsed by prominent reformers campaigning for "Dever and Decency" on his behalf,[45] including Charles Edward Merriam, Harriet Vittum, Harold L. Ickes, and Jane Addams.[49][60] The Ministerial Association of Chicago also endorsed Dever, calling him "the best mayor Chicago ever had ... [and] as loyal as a Catholic as he is [a] citizen".[61] He was backed by businessmen Sewell Avery, Julius Rosenwald, and W. A. Wieboldt,[49] as well as university presidents Max Mason and Walter Dill Scott and attorney Orville James Taylor.[49] He was also backed by socialites Louise deKoven Bowen and Edward Ryerson Jr, as well as builder Potter Palmer and Donald Richberg.[49] School superintendent William McAndrew distributed a latter to school principals urging for people to vote Dever.[46] Four of the city's daily newspapers backed Dever, as did the city's largest Polish, Jewish, and Italian newspapers.[25]

Robertson was supported by the incumbent[i] 43rd ward alderman ,[63] whose opponent Titus Haffa endorsed Thompson.[64] Henry F. Batterman, Lundin's 41st ward committeeman, supported Robertson before crossing over to Thompson.[56]

Result[]

Thompson won the election with more than 51 percent of votes cast,[38] carrying 28 of the city's 50 wards.[44] Dever's campaign ultimately failed to achieve momentum; Thompson had dominated the discourse early on and left Dever's supporters struggling to react to Thompson's campaign and ultimately failing to fully promote Dever's own message.[47]

Dever saw a significant decline in support from the Democratic party's stronghold, the city's white, working-class, inner-city wards.[47] His support improved in traditionally Republican White Anglo-Saxon Protestant precincts along Chicago's lakeshore.[47] Thompson carried the black vote by more than 10 to 1,[47] taking the three wards of Chicago's "black belt" by more than 59,000 votes.[65] According to one study, Thompson received 42.20 percent of the Polish-American vote, Dever 54.07 percent and Robertson 3.73 percent;[66] other sources suggest Thompson may have carried as much as 46 percent of the Polish-American vote.[67] By some accounts, Thompson carried 41 percent of the Czech-American vote and 43 percent of the Lithuanian-American vote, groups that typically firmly supported Democrats.[67] He also won more than 60 percent of the German-American and Swedish-American votes,[68] as well as the Italian-American and Jewish votes.[67] Edward Mazur divided his study of the Jewish vote into two groups, the European/German Jews and the Eastern European Jews.[69] He found that Eastern European Jewish precincts were carried by Thompson 55 to 41 percent, while the German Jewish precincts were carried by Dever 62 to 35 percent.[69]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | William Hale Thompson | 515,716 | 51.58 | |

| Democratic | William Emmett Dever (incumbent) | 432,678 | 43.28 | |

| People's Ownership Smash Crime Rings | John Dill Robertson | 51,347 | 5.14 | |

| Socialist | George Koop | 2 | 0.00 | |

| Turnout | 999,743 | 100.00 | ||

Aftermath[]

The results of the election damaged Chicago's reputation nationally.[45][71] Will Rogers remarked that "They was trying to beat Bill [Thompson] with the Better Element vote. The trouble with Chicago is that there ain't much Better Element."[j][45][72] The St. Louis Star declared that "Chicago is still a good deal of a Wild West town, where a soapbox showman extracting white rabbits from a gentleman's plug hat still gets a better hearing than a man in a sober suit talking business."[45] The campaign was such that philosopher Will Durant wondered whether democracy was dead.[74]

Many experts concluded that Thompson had won because of his skilled campaigning, providing entertainment while Dever called for virtue.[75] Elmer Davis of Harper's Magazine mused that the mystery was not that Dever lost but that he had received 430,000 votes.[76] George Schottenhamel, writing in 1952 for the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, argued that Dever "would have been easy opposition for any candidate" running "on a campaign of 'Dever and Decency' despite four years of rampant crime in Chicago".[77]

Nobody had expected Robertson to win.[78] The Chicago Tribune noted that he had finished a "poor third" and polled "only" 51,209 votes;[79] The Daily Independent of Murphysboro considered him to have finished at a "hopeless third".[80] Koop's performance of two votes was picked up by the Associated Press[81] and used by an editorial of the Ottawa Citizen as evidence that the threat of socialism was overblown.[82]

The election was marked by an unusually low level of crime: only one ballot box theft and a negligible amount of violence.[83][84] Some claimed that this was due to Capone using his men to guard polling stations and ensure votes for Thompson, but contemporary accounts make no mention of gang activity and police were dispatched to guard polling stations, aided by City Hall employees.[84] Police attributed the quiet at least in part to the death of Drucci,[83] who had allegedly raided the downtown offices of the Dever-supporting 42nd Ward alderman Dorsey Crowe the day before the election and was killed by police upon his arrest later that night.[84]

At his inaugural address, Thompson reiterated his pledge to oust Superintendent McAndrew.[85] In August 1927, the Chicago Board of Education, now under Thompson's influence after he appointed a number new members, voted to charge McAndrew with insubordination and lack of patriotism, suspending him pending a trial held by the board. The trial would last months, and the Chicago Board of Education would find McAndrew guilty. The Cook County Superior Court would later void this decision.[86]

Thompson would lose to Democrat Anton Cermak in the 1931 Chicago mayoral election[54] as his public approval fell victim to continuing crime and the Great Depression.[87] Historians generally consider him one of the most unethical mayors in American history, in large part due to his alliance with Capone.[88] Dever would serve as the vice president of a bank and died of pancreatic cancer in 1929.[89] Robertson was re-elected as the West Park President two days after the election,[90] and died in 1931 of heart disease.[91] To date, this is the last mayoral election in Chicago won by a Republican candidate.[k][54]

Notes[]

- ^ $360,000 in 2018. Thompson split the cost with allies William Lorimer and George F. Harding.[10]

- ^ One of 22 organizations that would be merged to form the Chicago Park District in 1934.[19]

- ^ At the time, Chicago's streetcar lines were managed by Chicago Surface Lines[32] while the "L" was under the control of the Chicago Rapid Transit Company[32] and the buses were operated by the Chicago Motor Coach Company,[33] all private corporations.[32] Public control would come with the formation of the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) to control the "L" and streetcars in 1947,[32] and complete consolidation took place when the CTA acquired the Chicago Motor Coach Company in 1952.[33]

- ^ Data missing for McCaffrey from the 5th ward[24][26]

- ^ The State Street Subway would open in 1943.[50]

- ^ $1.4 million in 2018

- ^ $7.2 million in 2018

- ^ $720,000 in 2018

- ^ Albert had been defeated by Haffa in the first-round aldermanic election.[62] However, he filed an appeal to have the result struck, and at the time of the endorsement had gained a new race in the runoff,[63] which he would win.[39] Ultimately, however, the council would vote to unseat him in favor of Haffa on October 31, claiming that the judge in the case had erred in counting spoiled ballots to determine the majority needed to avoid a runoff and thereby granting Albert a new race.[64]

- ^ Rogers is sometimes erroneously[72] said to have written this in response to Thompson's 1915 victory.[73]

- ^ Chicago mayoral elections became nonpartisan in 1995, effective 1999.[92] Since that time, all the winners—Richard M. Daley,[54] Rahm Emanuel, and Lori Lightfoot[93]—have been de facto Democrats.

References[]

- ^ Schmidt 1995 pp. 87–89

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schmidt 1995 p. 89

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schmidt 1995 p. 90

- ^ Schmidt 1995 p. 97

- ^ Schmidt 1995 p. 93

- ^ Schmidt 1989 p. 148

- ^ Schmidt 1989 p. 150

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nichols, Jeff (June 2, 2017). "Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson used 'America First' decades before Trump". Chicago Reader. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schottenhamel p. 42

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schottenhamel p. 41

- ^ Schottenhamel p. 43

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schottenhamel p. 32

- ^ "Centennial List of Mayors, City Clerks, City Attorneys, City Treasurers, and Aldermen, elected by the people of the city of Chicago, from the incorporation of the city on March 4, 1837, to March 4, 1937, arranged in alphabetical order, showing the years during which each official held office". Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Schottenhamel p. 33

- ^ Schottenhamel pp. 42–43

- ^ "Dr. Robertson Resigns". The Daily Pantagraph. 76 (28). February 2, 1922. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "DR. J.D. ROBERTSON OF CHICAGO DIES; Former Health Commissioner Succumbs to Heart Disease at the Age of 60. RAN FOR MAYOR IN 1927 Broke With Thompson to Head Independents--Organized Loyola University's Medical School". The New York Times. August 21, 1931. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Douglas, W. A. S. (January 3, 1927). "Dr. Robertson Puts Out Poetry To Win Chicago Women's Votes". The Baltimore Sun. 180 (40D). p. 1. Retrieved January 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "History of Chicago's Park". Chicago Park District. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Schmidt 1989 p. 154

- ^ Evans, Arthur (February 9, 1927). "Litsinger cites fee scandal of Thompson rule". Chicago Tribune. 86 (34). p. 1. Retrieved January 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Selzer, Adam (February 13, 2015). "Rahm might be bad, but Chicago's last Republican mayor was worse". TimeOut. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ Bright pp. 257–258

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Canvassing Sheet of Primary Election in the City of Chicago—February 22nd, 1927. The Board of Election Commissioners of the City of Chicago and ex-officio that of the City of Chicago Heights, the Town of Cicero and the Village of Summit. February 22, 1927.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Schmidt 1989 p. 156

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Dever is ready;gives outline of platform". Chicago Tribune. 86 (46). February 23, 1927. p. 1. Retrieved December 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Evans, Arthur (February 25, 1927). "Call Political Einsteins for Vote Analysis". Chicago Tribune. 86 (48). p. 6. Retrieved March 18, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Evans, Arthur (February 3, 1927). "Redeem G.O.P., Litsinger plea; race speeds up". Chicago Tribune. 86 (29). p. 4. Retrieved January 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Evans, Arthur (February 12, 1927). "O'Hara Pulls Out". Chicago Tribune. 86 (37). p. 5. Retrieved January 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Litsinger for subways now, platform says". Chicago Tribune. 86 (8). January 10, 1927. p. 8. Retrieved January 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bukowski pp. 182–183

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "History – The CTA is created (1947)". Chicago "L".org. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson, Mark R.; Porter, Stephen R.; Reiff, Janice L. "Chicago Motor Coach Co". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bukowski p. 183

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Evans, Arthur (February 18, 1927). "Big Bill mauls Doctor Dill for being unrefined". Chicago Tribune. 86 (42). p. 5. Retrieved March 18, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bright p. 249

- ^ Evans, Arthur (February 23, 1927). "Litsinger hit 2 to 1 in every ward but one". Chicago Tribune. 86 (46). p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Elections – City of Chicago – April 5th, 1927. The Board of Election Commissioners of the City of Chicago and ex-officio that of the City of Chicago Heights, the Town of Cicero and the Village of Summit. April 5, 1927.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Albert defeats Haffa in bitter Council battle". Chicago Tribune. 86 (82). April 6, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved December 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tarvardian, Arthur Norman (1992). "Battle Over the Chicago Schools: The Superintendency of William Mcandrew". Loyola University Chicago. p. 210. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Schmidt 1995 p. 94

- ^ Bright p. 242

- ^ Bright p. 253

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Schottenhamel p. 44

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Teaford p. 199

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Herrick, Mary J. (1971). The Chicago schools : a Social and Political History. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications. pp. 166–168. ISBN 080390083X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Schmidt 1995 p. 95

- ^ Bright p. 250

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Schmidt 1989 p. 157

- ^ "Operations – Lines -> State Street Subway". Chicago-l.org. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ Schottenhamel pp. 43–44

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bukowski p. 182

- ^ Evans, Arthur (March 22, 1927). "Robertson dares razzer to face him in person". Chicago Tribune. 86 (69). p. 4. Retrieved October 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Chicago Mayors, 1837–2007". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago History Museum. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ "Union Labor presents a solid front for Wm. Hale Thompson for Mayor". Chicago Tribune. 86 (79). April 2, 1927. p. 8. Retrieved March 18, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Evans, Arthur (March 13, 1927). "G.O.P. groups spurn Big Bill, turn to Dever". The Chicago Tribune. 86 (11). p. 1. Retrieved January 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eig pp. 94–95

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Schmidt 1989 p. 162

- ^ Bukowski p. 187

- ^ Eig p. 95

- ^ "Ministers Endorse Dever". The South Bend Tribune. 53 (319). April 15, 1927. p. 2. Retrieved March 18, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hewitt, Oscar (February 23, 1927). "Barbee, Albert, and Fick go into discard". Chicago Tribune. 86 (46). p. 1. Retrieved April 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Albert swings to Dr. Dill in 43rd ward race". Chicago Tribune. 86 (12). March 20, 1927. p. 7. Retrieved December 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Albert ousted; Haffa sworn in as Alderman". Chicago Daily Tribune. 86 (209). September 1, 1927. p. 3. Retrieved January 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Schottenhamel pp. 44–45

- ^ Kantowicz p. 79

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bukowski p. 186

- ^ Bukowski pp. 186–187

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schmidt 1989 p. 166

- ^ Schmidt 1989 Table 3 (p. 187)

- ^ Schmidt 1989 p. 167

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rogers, Will (April 7, 1927). "Will Rogers' Dispatch". The Boston Globe. 111 (97). p. 1. Retrieved April 15, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Schottenhamel p. 35

- ^ Schmidt 1989 p. 161

- ^ Schmidt 1995 pp. 95–96

- ^ Schmidt 1995 p. 96

- ^ Schottenhamel p. 49

- ^ Schmidt 1989 pp. 161–162

- ^ Evans, Arthur (April 6, 1927). "Dever beaten in battle of 993,617 votes". Chicago Tribune. 86 (82C). p. 1. Retrieved January 7, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Buckingham, Max (April 6, 1927). "Thompson wins Chicago mayoralty". The Daily Independent. p. 1. Retrieved January 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Evidently married". The Record. 32 (292). Associated Press. May 23, 1927. p. 17. Retrieved January 7, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mr. Koop's two votes". The Ottawa Citizen. 84 (256). April 15, 1927. p. 22. Retrieved January 7, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Quiet election surprises Cops guarding polls". The Chicago Tribune. 86 (82). April 6, 1927. p. 7. Retrieved January 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Eig p. 96

- ^ "Mayor William Hale Thompson Inaugural Address, 1927". www.chipublib.org. Chicago Public Library. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Schmidt, John R. (September 30, 2011). "The trial of the school superintendent". WBEZ Chicago. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Schottenhamel pp. 45–46

- ^ Grossman p. 329

- ^ "William Dever Cancer Victim". The Dispatch. 52. September 4, 1929. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dr. Robertson re-elected Chief of West Parks". Chicago Tribune. 86 (84). April 8, 1927. p. 22. Retrieved December 22, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Foe of Thompson dies at Fontana". The Dispatch. 54. Associated Press. August 20, 1931. p. 1. Retrieved April 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shefsky, Jay (February 26, 2019). "How, and Why, Chicago Has Nonpartisan Elections". WTTW. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "New Face and Longtime Politician Vying for Chicago Mayor". WTTW. Associated Press. April 1, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

Works cited[]

- Bright, John (1930). Hizzoner Big Bill Thompson, an idyll of Chicago. New York, New York: Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith. OCLC 557783528.

- Bukowski, Douglas (1998). Big Bill Thompson, Chicago, and the Politics of Image. Urbana, Illinois and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02365-X.

- Eig, Jonathan (2010). Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America's Most Wanted Gangster. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-8059-1.

- Grossman, Mark (2008). Political Corruption in America: An Encyclopedia of Scandals, Power, and Greed. Armenia, New York: Grey House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59237-297-3.

- Kantowicz, Edward (1972). "The Emergence of the Polish-Democratic Vote in Chicago". Polish American Studies. 29 (1): 67–80. JSTOR 20147849.

- Schmidt, John R. (1989). "The Mayor Who Cleaned Up Chicago" A Political Biography of William E. Dever. DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-87580-144-7.

- Schmidt, John R. (1995). "William E. Dever (1923–1927)". In Green, Paul M.; Holli, Melvin G. (eds.). The Mayors: The Chicago Political Tradition (Revised ed.). Carbondale, Illinois and Edwardsville, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 82–98. ISBN 0-8093-1963-2.

- Schottenhamel, George (1952). "How Big Bill Thompson Won Control of Chicago". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 45 (1): 30–49. JSTOR 40189189.

- Teaford, Jon C. (1993). Cities of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Midwest. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20914-5.

- Mayoral elections in Chicago

- 1927 United States mayoral elections

- 1927 Illinois elections

- 1920s in Chicago