1993 Storm of the Century

Category 5 "Extreme" (RSI/NOAA: 24.63) | |

Satellite image by NASA of the storm on March 13, 1993, at 10:01 UTC. | |

| Type | Extratropical cyclone Superstorm Nor'easter Blizzard Tornado outbreak Derecho Ice storm Gulf low |

|---|---|

| Formed | March 12, 1993 |

| Dissipated | March 15, 1993 |

| Highest winds |

|

| Lowest pressure | 960 mb (28.35 inHg) |

| Lowest temperature | −12 °F (−24 °C) |

| Tornadoes confirmed | 11 on March 13 (all in Florida) |

| Max. rating1 | F2 tornado |

| Duration of tornado outbreak2 | 1 hour, 32 minutes |

| Maximum snowfall or ice accretion | Snow – 56 in (140 cm) at Mt. Le Conte, Tennessee |

| Fatalities | 318 fatalities |

| Damage | > $2 billion (1993 USD) (Second-costliest winter storm on record) |

| Power outages | > 10,000,000 |

| Areas affected | Eastern United States, Canada, Mexico, Cuba, Bahamas, Bermuda |

Part of the 1992–93 North American winter and tornado outbreaks of 1993 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale 2Time from first tornado to last tornado | |

The 1993 Storm of the Century (also known as the 93 Superstorm, The No Name Storm, or the Great Blizzard of '93/1993) was a large cyclonic storm that formed over the Gulf of Mexico on March 12, 1993. The storm was unique and notable for its intensity, massive size, and wide-reaching effects; at its height, the storm stretched from Canada to Honduras.[1] The cyclone moved through the Gulf of Mexico and then through the eastern United States before moving on to eastern Canada. The storm eventually dissipated in the North Atlantic Ocean on March 15.

Heavy snow was first reported in highland areas as far south as Alabama and northern Georgia, with Union County, Georgia reporting up to 35 inches (89 cm) of snow. Birmingham, Alabama, reported a rare 13 in (33 cm) of snow.[2][3] The Florida Panhandle reported up to 4 in (10 cm) of snow,[4] with hurricane-force wind gusts and record low barometric pressures. Between Louisiana and Cuba, the hurricane-force winds produced high storm surges across the big bend of Florida which, in combination with scattered tornadoes, killed dozens of people.

Record cold temperatures were seen across portions of the Southern United States and Eastern United States in the wake of this storm. In the United States, the storm was responsible for the loss of electric power to more than 10 million households. An estimated 40 percent of the country's population experienced the effects of the storm[5] with a total of 208 fatalities.[1] In all, the storm killed 318 people, and caused $2 billion (1993 USD) in damages.

The greatest recorded snowfall amounts were at Mount Le Conte in Tennessee, where 56 inches of snow fell, and Mount Mitchell in North Carolina, the tallest mountain in eastern North America, where 50 inches (130 cm) were measured to fall and 15-foot (4.6 m) snow drifts were reported.[6]

Meteorological history[]

A volcanic winter is thought to have started with the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo. The temperature in the stratosphere rose to several degrees higher than normal, due to the absorption of radiation by the aerosol. The stratospheric cloud from the eruption persisted in the atmosphere for three years. The eruption, while not directly responsible, may have played a part in the formation of the 1993 Storm of the Century.[7]

During March 11 and 12, 1993, temperatures over much of the eastern United States began to drop as an arctic high pressure system built over the Midwestern United States and the Great Plains. Concurrently, an extratropical area of low pressure formed over Mexico along a stationary front draped west to east. By the afternoon of March 12, a defined airmass boundary was present along the deepening low. An initial burst of convective precipitation off the southern coast of Texas (facilitated by the transport of tropical moisture into the region) enabled initial intensification of the surface feature on March 12. Supported by a strong split-polar jet stream and a shortwave trough, the nascent system rapidly deepened.[8] The system's central pressure fell to 991 mbar (29.26 inHg) by 00:00 UTC on March 13. A powerful low-level jet over eastern Cuba and the Gulf of Mexico enhanced a cold front extending from the low southward to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Furthermore, the subtropical jet stream was displaced unusually far south, reaching into the Pacific Ocean near Central America and extending toward Honduras and Jamaica. Intense ageostrophic flow was noted over the southern United States, with winds flowing perpendicular to isobars over Louisiana.[8]

As the area of low pressure moved through the central Gulf of Mexico, a short wave trough in the northern branch of the jet stream fused with the system in the southern stream, which further strengthened the surface low. A squall line developed along the system's cold front, which moved rapidly across the eastern Gulf of Mexico through Florida and Cuba.[8] The cyclone's center moved into north-west Florida early on the morning of March 13, with a significant storm surge in the northwestern Florida peninsula that drowned several people. This initially caused the storm to be a blizzard but also cyclonic.

Barometric pressures recorded during the storm were low. Readings of 976.0 millibars (28.82 inHg) were recorded in Tallahassee, Florida, and even lower readings of 960.0 millibars (28.35 inHg) were observed in New England. Low pressure records for March were set in areas of twelve states along the Eastern Seaboard,[9] with all-time low pressure records set between Tallahassee and Washington, D.C.[10] Snow began to spread over the eastern United States, and a large squall line moved from the Gulf of Mexico into Florida and Cuba. The storm system tracked up the East Coast during Saturday and into Canada by early Monday morning. In the storm's wake, unseasonably cold temperatures were recorded over the next two days in the Southeast.

Forecasting[]

The 1993 Storm of the Century marked a milestone in the weather forecasting of the United States. By March 8, 1993, several operational numerical weather prediction models and medium-range forecasters at the United States National Weather Service recognized the threat of a significant snowstorm. This marked the first time National Weather Service meteorologists were able to predict accurately a system's severity five days in advance. Official blizzard warnings were issued two days before the storm arrived, as shorter-range models began to confirm the predictions. Forecasters were finally confident enough of the computer-forecast models to support decisions by several northeastern states to declare a state of emergency even before the snow started to fall.[11]

Impact[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2018) |

The storm complex was large and widespread, affecting at least 26 US states and much of eastern Canada. It brought in cold air along with heavy precipitation and hurricane-force winds which, ultimately, caused a blizzard over the affected area; this also included thundersnow from Georgia to Pennsylvania and widespread whiteout conditions. Snow flurries were seen in the air as far south as Jacksonville, Florida,[12] and some areas of central Florida received a trace of snow. The storm severely impacted both ground and air travel. Airports were closed all along the eastern seaboard, and flights were cancelled or diverted, thus stranding many passengers along the way. Every airport from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Tampa, was closed for some time because of the storm. Highways were also closed or restricted all across the affected region, even in states generally well prepared for snow emergencies.

| Place | Total |

|---|---|

| Mount Mitchell, NC | 56 in (142 cm) |

| Snowshoe, WV | 44 in (110 cm)[13] |

| Syracuse, NY | 43 in (110 cm)[13] |

| Tobyhanna, PA | 42 in (110 cm)[13] |

| Lincoln, NH | 35 in (89 cm)[13] |

| Blairsville, GA | 35 in (89 cm)[3] |

| Boone, NC | 33 in (84 cm) |

| Gatlinburg, TN | 30 in (76 cm)[13] |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 25.2 in (64 cm) |

| Chattanooga, TN | 23 in (58 cm)[13] |

| London, KY | 22 in (56 cm)[14] |

| Worcester, MA | 20.1 in (51 cm)[15] |

| Ottawa, ON | 17.7 in (45 cm)[16] |

| Birmingham, AL | 13 in (33 cm)[17] |

| Montreal, QC | 16.1 in (41 cm)[18] |

| Trenton, NJ | 14.8 in (38 cm) |

| Dulles, VA (30 miles NW of Washington, D.C.) | 14.1 in (36 cm) |

| Birmingham, AL | 13 in (33 cm)[19] |

| Boston, MA | 12.8 in (33 cm) |

| New York, NY (LaGuardia) | 12.3 in (31 cm) |

| Baltimore, MD (BWI) | 11.9 in (30 cm) |

| Atlanta, GA (northern suburbs) | 10.0 in (25 cm) |

| Huntsville, AL | 7 in (18 cm)[20] |

| Arlington, VA (National Airport) | 6.6 in (17 cm) |

| Atlanta, GA (Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport) | 4.5 in (11 cm)[13] |

| Mobile, AL | 3 in (7.6 cm) |

| Knoxville, TN | 15 in (38 cm) |

Some affected areas in the Appalachian Mountain region saw 5 feet (1.5 m) of snow, and snowdrifts as high as 35 feet (11 m). Mount Mitchell, NC recorded 56" and Mount Le Conte, Tennessee recorded 50" of snowfall. The volume of the storm's total snowfall was later computed to be 12.91 cubic miles (53.8 km3), an amount which would weigh (depending on the variable density of snow) between 5.4 and 27 billion tons.

The weight of the record snowfalls collapsed several factory roofs in the South; and snowdrifts on the windward sides of buildings caused a few decks with substandard anchoring to fall from homes. Though the storm was forecast to strike the snow-prone Appalachian Mountains, hundreds of people were nonetheless rescued from the Appalachians, many caught completely off guard on the Appalachian Trail or in cabins and lodges in remote locales. Snow drifts up to 14 feet (4.3 m) were observed at Mount Mitchell. Snowfall totals of between 2 and 3 feet (0.61 and 0.91 m) were widespread across northwestern North Carolina. Boone, North Carolina—in a high-elevation area accustomed to heavy snowfalls—was nonetheless caught off-guard by more than 30 inches (76 cm) of snow and 24 hours of temperatures below 11 °F (−12 °C). Boone's Appalachian State University closed that week, for the first time in its history. Stranded motorists at Deep Gap broke into Parkway Elementary School to survive, and National Guard helicopters dropped hay in fields to keep livestock from starving in northern N.C. mountain counties.

In Virginia, the LancerLot sports arena in Vinton collapsed due to the weight of the record snowfall, forcing the Virginia Lancers of the ECHL to relocate to nearby Roanoke and become the Roanoke Express. Also collapsing were the roofs of a Lowe's store in Christiansburg and the Dedmon Center, at Radford University. Thousands of travelers were stranded along interstate highways in Southwest Virginia.[21] Electricity was not restored to many isolated rural areas for up to three weeks, with power outages occurring all over the east. Nearly 60,000 lightning strikes were recorded as the storm swept over the country for a total of 72 hours. As one of the most powerful, complex storms in recent history, this storm was described as the "Storm of the Century" by many of the areas affected.

Gulf of Mexico[]

The United States Coast Guard dealt with "absolutely incredible, unbelievable" conditions within the Gulf of Mexico. The 200-foot (61 m) freighter Fantastico sank 70 miles (110 km) off Ft. Myers, Florida, and seven of her crew died when a Coast Guard helicopter was forced back to base due to low fuel levels after rescuing three of her crew. The 147-foot (45 m) freighter Miss Beholden ran aground on a coral reef 10 miles (16 km) from Key West, Florida. Several other smaller vessels sank in the rough seas. In all, the Coast Guard rescued 235 people from over 100 boats across the Gulf of Mexico during the tempest.[22]

Florida[]

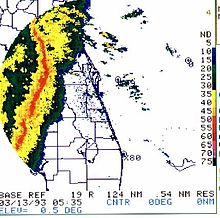

Besides producing record-low barometric pressure across a swath of the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic states, and contributing to one of the nation's biggest snowstorms, the low produced a potent squall line ahead of its cold front. The squall line produced a serial derecho as it moved into Florida and Cuba shortly after midnight on March 13. Straight-line winds gusted above 100 miles per hour (87 kn; 160 km/h) at many locations in Florida as the squall line moved through. A substantial tree fall was seen statewide from this system. The supercells in the derecho produced eleven tornadoes. The first tornado was an F2 that touched down in Chiefland at 04:38 UTC on March 13, damaging several mobile homes and downing trees and power lines. Three people were killed and seven people sustained injures. Around the same time, an F1 tornado was spawned near Crystal River. After moving eastward into the town, the twister damaged 15 homes, several of them severely. A total of three people were injured. The next tornado was a waterspout that moved ashore over Treasure Island around 05:00 UTC. Rated F0, the tornado deroofed one home, damaged several others, and impacted a few boats.[24]

Around 05:04 UTC, an F0 tornado was reported in New Port Richey, damaging several homes and injuring 11 people. About 16 minutes later, an F2 tornado formed to the southwest of Ocala. Many trees fell and several storage buildings and a warehouse suffered extensive damage, while one hangar was destroyed and two others received major damage at the Ocala International Airport. At 05:20 UTC, approximately the same time as the Ocala tornado, another twister – rated F1 – touched down near LaCrosse. Several trees and power lines were downed and a few homes were destroyed, one from a propane explosion. One person was killed and four others received injuries. About 10 minutes later, another F2 twister was spawned near Howey-in-the-Hills. It moved through Mount Dora, destroying 13 homes, substantially damaging 80 homes, and inflicting minor damage on 266 homes. One person, a 5-month-old baby, was killed, while two others were injured.[24]

At 05:30 UTC, a waterspout-turned F0 tornado tossed a 23 ft (7.0 m) sailboat about 300 ft (91 m) at the Davis Islands yacht club in Tampa, while five other boats broke loose from their cradles and twelve were smashed into the seawall. About 30 minutes later, an F1 tornado formed in Jacksonville, demolishing four dwellings and damaging sixteen others.[24] Also at 06:00 UTC, an F0 tornado spawned near Bartow snapped a few trees and damaged a few doors. The eleventh and final tornado developed in Jacksonville at 06:10 UTC. The twister damaged a few trees near the Jacksonville International Airport. At the airport itself, the tornado damaged several jetways and service vehicles, while a Boeing 737 was pushed about 40 ft (12 m).[24]

A substantial storm surge was also generated along the gulf coast from Apalachee Bay in the Florida Panhandle to north of Tampa Bay. Due to the angle of the coast relative to the approaching squall, Taylor County along the eastern portion of Apalachee Bay and Hernando County north of Tampa were especially hard-hit.[4]

Storm surges in those areas reached up to 12 feet (3.7 m),[23] higher than many hurricanes. With little advance warning of incoming severe conditions, some coastal residents were awakened in the early morning of March 13 by the waters of the Gulf of Mexico rushing into their homes.[25] More people died from drowning in this storm than during Hurricanes Hugo and Andrew combined.[5] Overall, the storm's surge, winds, and tornadoes damaged or destroyed 18,000 homes.[26] A total of 47 lives were lost in Florida due to this storm.[4]

Cuba[]

In Cuba, wind gusts reached 100 mph (160 km/h) in the Havana area. A survey conducted by a research team from the Institute of Meteorology of Cuba suggests that the maximum winds could have been as high as 130 mph (210 km/h). It is the most damaging squall line ever recorded in Cuba.

There was widespread and significant damage in Cuba, with damage estimated as intense as F2.[8] The squall line finally moved out of Cuba near sunrise, leaving 10 deaths and US$1 billion in damage on the island.

North Atlantic[]

The cargo ship Gold Bond Conveyor en route from Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada to Tampa, Florida foundered in the Atlantic Ocean 60 nautical miles (110 km) SE of Sable Island, Nova Scotia with the loss of all 33 crew.[27] It is thought that water entered the hold where gypsum ore was being stored and caused the rock to shift and harden. This instability compounded with winds of 90 miles an hour (145 km/h) and 100-foot (30 m) waves led to her sinking. The Liberian-flagged ship was owned by Skaarup Shipping Corp., of Greenwich, Connecticut, and under charter to National Gypsum Co., a U.S. company. The ship had previously survived the Perfect Storm of 1991 two years earlier.[28]

Tornadoes spawned by the storm[]

| FU | F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| F# | Location | County | Time (UTC) | Path length | Fatalities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | ||||||

| F2 | NW of Chiefland | Levy | 0438 | 1 mile (1.6 km) | 3 deaths | |

| F1 | E of Crystal River | Citrus | 0438 | 0.5 miles (0.80 km) | ||

| F0 | Treasure Island | Pinellas | 0500 | 0.2 miles (0.32 km) | ||

| F0 | New Port Richey area | Pasco | 0504 | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | ||

| F2 | Ocala area | Marion | 0520 | 15 miles (24 km) | ||

| F1 | N of LaCrosse | Alachua | 0520 | 0.8 miles (1.3 km) | 1 death | |

| F2 | NW of Howey-in-the-Hills to Altamonte Springs | Lake | 0530 | 30 miles (48 km) | 1 death | |

| F1 | Tampa area | Hillsborough | 0530 | 0.6 miles (0.97 km) | ||

| F1 | Jacksonville area (1st tornado) | Duval | 0600 | 0.8 miles (1.3 km) | ||

| F0 | Bartow area | Polk | 0600 | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | ||

| F0 | Jacksonville area (2nd tornado) | Duval | 0610 | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | ||

| Sources:

Tornado History Project Storm Data – March 12, 1993, Tornado History Project Storm Data – March 13, 1993 | ||||||

See also[]

- List of derecho events

- Great Flood of 1993

- Hurricane Sandy

- Early 2014 North American cold wave

- Snowmageddon

- January 2016 North American blizzard

- February 13–17, 2021 North American winter storm – The costliest winter storm on record, also killed 200+ people

- The Day After Tomorrow - Uses archive footage of the 1993 storm.

References[]

- ^ a b Armstrong, Tim. "Superstorm of 1993: "Storm of the Century"". NOAA. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ "Birmingham Cold Weather Facts (updated Nov. 24, 2015)". National Weather Service-Birmingham. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ a b "21 years ago, Atlanta slammed by rare blizzard". ajc.com. March 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c National Climatic Data Center (1993). "Event Details". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Office of Meteorology (August 24, 2000). "Assessment of the Superstorm of March 1993" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ^ "On This Day: The 1993 Storm of the Century". National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). March 9, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Stevens, William (March 14, 1993). "THE BLIZZARD OF '93: Meteorology; 3 Disturbances Became a Big Storm". The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Arnaldo P. Alfonso; Lino R. Naranjo (March 1996). "The 13 March 1993 Severe Squall Line over Western Cuba". Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 11 (1): 89–102. Bibcode:1996WtFor..11...89A. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1996)011<0089:TMSSLO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434.

- ^ David M. Roth (March 2016). "Occurrence of March Record Low SLPs". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ David M. Roth (2016). "Months when All-Time Record Low SLPs Were Set". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (December 14, 2006). "Forecasting the "Storm of the Century"". Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ "History | Weather Underground". Wunderground.com. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Neal Lott (May 14, 1993). "The Big One! A Review of the March 12–14, 1993 "Storm of the Century" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ David Sander; Glen Conner. "Fact Sheet: Blizzard of 1993". Archived from the original on December 2, 2005. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ Mike Carbone; Neal Strauss; Frank Nocera; Dave Henry (March 16, 2001). "Top 10 Record Snowfalls of New England". National Weather Service Forecast Office, Taunton, Massachusetts. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ^ "Plus de 100 morts de Cuba au Quebec". La Presse. Reuters. March 15, 1993. p. A3.

- ^ "Birmingham Cold Weather Facts". National Weather Service-Birmingham. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Lapointe, Pascal (March 15, 1993). "Le Québec y a goûté !". Le Soleil. p. A1.

- ^ Gray, Jeremy (March 11, 2013). "Where were you during the Blizzard of '93? AL.com wants your pictures, memories". al.com. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ Wilhelm, Mike (March 11, 2013). "20th Anniversary of Blizzard of 1993". Mike Wilhelm's Alabama Weather Blog. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Region's Blizzard of '93still widely remembered | Weather | roanoke.com".

- ^ John Galvin (December 18, 2009). "Superstorm: Eastern and Central U.S., March 1993". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Communication, Inc.: 1. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ a b National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1994). "Superstorm of March 1993" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 35 (3). March 1993. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Rick Gershman (March 18, 1993). "Losing a home, then losing a life". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ St. Petersburg Times (1999). "A storm with no name". Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ James Bone (16 March 1993). The Times (64593). London. col E-F, p. 11."British crew lost as storm sinks freighter".

- ^

"Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1993 Storm of the Century. |

- Blizzards in the United States

- Blizzards in Canada

- Nor'easters

- 1993 meteorology

- 1993 natural disasters

- 1993 natural disasters in the United States

- 1993 disasters in Canada

- 1993 in Cuba

- Derechos in the United States

- F2 tornadoes

- Tornadoes in the United States

- Natural disasters in Alabama

- Natural disasters in Connecticut

- Natural disasters in Florida

- Natural disasters in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Natural disasters in Kentucky

- Natural disasters in New Brunswick

- Natural disasters in New Hampshire

- Natural disasters in New York (state)

- Natural disasters in North Carolina

- Natural disasters in Nova Scotia

- Natural disasters in Ontario

- Natural disasters in Pennsylvania

- Natural disasters in Quebec

- Natural disasters in Tennessee

- Natural disasters in Virginia

- Natural disasters in West Virginia

- Natural disasters in Washington, D.C.

- March 1993 events in North America

- Volcanic winters