2022 Ukraine cyberattacks

| Russo-Ukrainian War |

|---|

|

| Major events |

|

| Major topics |

|

| Related topics |

|

On 14 January 2022, a cyberattack took down more than a dozen of Ukraine's government websites during the 2021–2022 Russo-Ukrainian crisis.[1] According to Ukrainian officials, around 70 government websites, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Cabinet of Ministers, and the Security and Defense Council, were attacked. Most of the sites were restored within hours of the attack.[2] On 15 February, another cyberattack took down multiple government and bank services.[3][4]

Background[]

At the time of the attack, tensions between Russia and Ukraine were high, with over 100,000 Russian troops stationed near the border with Ukraine and talks between Russia and NATO ongoing.[1] The US government alleged that Russia was preparing for an invasion of Ukraine, including "sabotage activities and information operations". The US also allegedly found evidence of "a false-flag operation" in Eastern Ukraine, which could be used as a pretext for invasion.[2] Russia denies the accusations of an impending invasion, but has threatened "military-technical action" if its demands are not met, especially a request that NATO never admit Ukraine to the alliance. Russia has spoken strongly against the expansion of NATO to its borders.[2]

January attacks[]

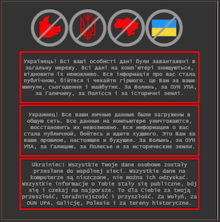

The attacks on 14 January 2022 consisted of the hackers replacing the websites with text in Ukrainian, erroneous Polish, and Russian, which state "be afraid and wait for the worst" and allege that personal information has been leaked to the internet.[5] About 70 government websites were affected, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Cabinet of Ministers, and the Security and Defense Council.[6] The SBU has stated that no data was leaked. Soon after the message appeared, the sites were taken offline. The sites were mostly restored within a few hours.[1] Deputy secretary of the NSDC Serhiy Demedyuk, stated that the Ukrainian investigation of the attack suspects that a third-party company's administration rights were used to carry out the attack. The unnamed company's software had been used since 2016 to develop government sites, most of which were affected in the attack.[6] Demedyuk also blamed UNC1151, a hacker group allegedly linked to Belarusian intelligence, for the attack.[7]

A separate destructive malware attack took place around the same time, first appearing on 13 January. First detected by the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC), malware was installed on devices belonging to "multiple government, non-profit, and information technology organizations" in Ukraine.[8] Later, this was reported to include the State Emergency Service and the Motor Transport Insurance Bureau.[9] The software, designated DEV-0586 or WhisperGate, was designed to look like ransomware, but lacks a recovery feature, indicating an intent to simply destroy files instead of encrypting them for ransom.[8] The MSTIC reported that the malware was programmed to execute when the targeted device was powered down. The malware would overwrite the master boot record (MBR) with a generic ransom note. Next, the malware downloads a second .exe file, which would overwrite all files with certain extensions from a predetermined list, deleting all data contained in the targeted files. The ransomware payload differs from a standard ransomware attack in several ways, indicating a solely destructive intent.[10] However, later assessments indicate that damage was limited, likely a deliberate choice by the attackers.[9]

On 19 January, the Russian advanced persistent threat (ATP) (also known as ) attempted to compromise a Western government entity in Ukraine.[11] Cyber espionage appears to be the main goal of the group,[11] which has been active since 2013; unlike most ATPs, Gamaredon broadly targets all users all over the globe (in addition to also focusing on certain victims, especially Ukrainian organizations[12]) and appears to provide services for other APTs.[13] For example, the threat group has attacked select systems that Gamaredon had earlier compromised and fingerprinted.[12]

Reactions to January attack[]

Russia[]

Russia denied allegations by Ukraine that it was linked to the cyberattacks.[14]

Ukraine[]

Ukrainian government institutions, such as the Center for Strategic Communications and Information Security and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, suggested that the Russian Federation was the perpetrator of the attack, noting that this would not be the first time that Russia attacked Ukraine.[5][15]

International organizations[]

European Union High Representative Josep Borrell said of the source of the attack: “One can very well imagine with a certain probability or with a margin of error, where it can come from.”[16] The Secretary General of NATO Jens Stoltenberg announced that the organization would increase its coordination with Ukraine on cyberdefense in the face of potential additional cyberattacks. NATO later announced that it would sign an agreement granting Ukraine access to its malware information sharing platform.[2][5]

February attacks[]

On 15 February, a large DDoS attack brought down the websites of the defense ministry, army, and Ukraine's two largest banks, PrivatBank and Oschadbank.[3][17][4] Cybersecurity monitor NetBlocks reported that the attack intensified over the course of the day, also affecting the mobile apps and ATMs of the banks.[3] The New York Times described it as "the largest assault of its kind in the country's history". Ukrainian government officials stated that the attack was likely carried out by a foreign government, and suggested that Russia was behind it.[18] Although there were fears that the denial-of-service attack could be cover for more serious attacks, a Ukrainian official said that no such attack had been discovered.[9]

According to UK government[19] and National Security Council of the US, the attack was performed by Russian Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU). American cybersecurity official Anne Neuberger stated that known GRU infrastructure has been noted transmitting high volumes of communications to Ukraine-based IP addresses and domains.[20] Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov denied that the attack originated from Russia.[21]

On 23 February, a third DDoS attack took down multiple Ukrainian government, military, and bank websites. Although military and banking websites were described as having “a more rapid recovery”, the SBU website was offline for an extended period.[22] Just before 5 pm, data wiping malware was detected on hundreds of computers belonging to multiple Ukrainian organizations, including in the financial, defense, aviation, and IT services sectors. ESET Research dubbed the malware HermeticWiper, named for its genuine code signing certificate from Cyprus-based company Hermetica Digital Ltd. The wiper was reportedly compiled on 28 December 2021, while Symantec reported malicious activity as early as November 2021, implying that the attack was planned months ahead of time. Symantec also reported wiper attacks against devices in Lithuania, and that some organizations were compromised months before the wiper attack. Similar to the January WhisperGate attack, ransomware is often deployed simultaneously with the wiper as a decoy, and the wiper damages the master boot record.[23][24]

A day prior to the attack, the EU had deployed a cyber rapid-response team consisting of about ten cybersecurity experts from Lithuania, Croatia, Poland, Estonia, Romania, and the Netherlands. It is unknown if this team helped mitigate the effects of the cyberattack.[25]

The attack coincided with the Russian recognition of separatist regions in eastern Ukraine and the authorization of Russian troop deployments there. The US and UK blamed the attack on Russia. Russia denied the accusations and called them “Russophobic”.[22]

March attacks[]

Beginning on 6 March, Russia began to significantly increase the frequency of its cyber-attacks against Ukrainian civilians.[26]

On 9 March alone, the Quad9 malware-blocking recursive resolver intercepted and mitigated 4.6 million attacks against computers and phones in Ukraine and Poland, at a rate more than ten times higher than the European average. Cybersecurity expert Bill Woodcock of Packet Clearing House noted that the blocked DNS queries coming from Ukraine clearly show an increase in phishing and malware attacks against Ukrainians, and noted that the Polish numbers were also higher than usual because 70%, or 1.4 million, of the Ukrainian refugees were in Poland at the time.[27] Explaining the nature of the attack, Woodcock said "Ukrainians are being targeted by a huge amount of phishing, and a lot of the malware that is getting onto their machines is trying to contact malicious command-and-control infrastructure."[26]

On March 28, RTComm.ru, a Russian Internet service provider, BGP hijacked Twitter's 104.244.42.0/24 IPv4 address block for a period of two hours and fifteen minutes.[28][29]

See also[]

- 2017 cyberattacks on Ukraine

- 2021–2022 Russo-Ukrainian crisis

- Kaspersky bans and allegations of Russian government ties#Russian invasion of Ukraine

References[]

- ^ a b c "Ukraine cyber-attack: Government and embassy websites targeted". BBC News. 2022-01-14. Archived from the original on 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b c d Polityuk, Pavel; Balmforth, Tom (2022-01-14). "'Be afraid': Ukraine hit by cyberattack as Russia moves more troops". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2022-01-14. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b c "Ukraine banking and defense platforms knocked out amid heightened tensions with Russia". NetBlocks. 2022-02-15. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24.

- ^ a b "Ukraine's defence ministry and two banks targeted in cyberattack". euronews. 2022-02-15. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23.

- ^ a b c Kramer, Andrew E. (2022-01-14). "Hackers Bring Down Government Sites in Ukraine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b Polityuk, Pavel (2022-01-14). "EXCLUSIVE Hackers likely used software administration rights of third party to hit Ukrainian sites, Kyiv says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ^ Polityuk, Pavel (2022-01-16). "EXCLUSIVE Ukraine suspects group linked to Belarus intelligence over cyberattack". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2022-02-18. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ^ a b "Destructive malware targeting Ukrainian organizations". Microsoft Security Blog. 2022-01-16. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ^ a b c "Cyberattacks knock out sites of Ukrainian army, major banks". AP NEWS. 2022-02-15. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (2022-01-16). "Microsoft Warns of Destructive Cyberattack on Ukrainian Computer Networks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- ^ a b Kyle Alspach (2022-02-04). "Microsoft discloses new details on Russian hacker group Gamaredon". VentureBeat. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ a b Charlie Osborne (2022-03-21). "Ukraine warns of InvisiMole attacks tied to state-sponsored Russian hackers". Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ Warren Mercer; Vitor Ventura (2021-02-23). "Gamaredon - When nation states don't pay all the bills". Cisco. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ McMillan, Robert; Volz, Dustin (2022-01-20). "Ukraine Hacks Signal Broad Risks of Cyberwar Even as Limited Scope Confounds Experts". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ^ "News Ukraine government websites hacked in 'global attack'". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2022-01-14. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Brzozowski, Alexandra; Pollet, Mathieu (2022-01-14). "EU pledges cyber support to Ukraine, pins hopes on Normandy format". www.euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-01. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- ^ Zilbermints, Regina (2022-02-15). "Ukraine Defense Ministry, banks hit by cyberattack amid tensions with Russia". TheHill. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24.

- ^ Hopkins, Valerie (2022-02-15). "A hack of the Defense Ministry, army and state banks was the largest of its kind in Ukraine's history". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-02-17. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ "Government response: UK assess Russian involvement in cyber attacks on Ukraine". UK government. 2022-02-18. Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ "Biden says he's now convinced Putin has decided to invade Ukraine, but leaves door open for diplomacy". CNN. 2022-02-19. Archived from the original on 2022-02-19.

- ^ "Нова кібератака на банки була "найбільшою в історії України" й досі триває". BBC. 2022-02-16. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ a b "Cyber-attacks bring down many Ukraine websites". BBC News. 2022-02-23. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ "HermeticWiper: New data‑wiping malware hits Ukraine". WeLiveSecurity. 2022-02-24. Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ "Ukraine: Disk-wiping Attacks Precede Russian Invasion". symantec-enterprise-blogs.security.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ "Ukraine: EU deploys cyber rapid-response team". BBC News. 2022-02-22. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ a b Krebs, Brian. "Recent 10x Increase in Cyberattacks on Ukraine". Krebs on Security. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

While our overall traffic dropped in Kyiv — and slightly increased in Warsaw due to infrastructure outages inside of Ukraine — the ratio of "good queries" to "blocked queries" has spiked in both cities. The spike in the blocking ratio Wednesday (March 9, 2022) afternoon in Kyiv was around 10x the normal level compared with other cities in Europe. This order-of-magnitude jump is unprecedented.

- ^ "Ukraine Refugee Situation". UNHCR.

- ^ Ullrich, Johannes. "BGP Hijacking of Twitter Prefix by RTComm.ru". ISC InfoSec. SANS. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ "Possible BGP Hijack". BGPStream. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- 2022 crimes in Ukraine

- 2022 in computing

- 2022 in Ukraine

- 2020s internet outages

- Cyberattacks

- Hacking in the 2020s

- January 2022 crimes in Europe

- Russo-Ukrainian War

- Anti-Ukrainian sentiment