Russia–Ukraine relations

| |

Russia |

Ukraine |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Ukrainian Embassy, Moscow | Russian Embassy, Kyiv |

| Russo-Ukrainian War |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

|

| Related topics |

|

Russia–Ukraine relations refers to the relations between the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Currently, the two countries are engaged in the Russo-Ukrainian War which started in 2014 following Russian annexation of Crimea from Ukraine. The modern bilateral relationship between the Russian Federation and Ukraine formally started during World War I as the former Russian Empire was going through its political reform. In 1920, the bilateral relationship between the two countries was changed as Ukraine was conquered by the Russian Red Army and Polish Army. In the 1990s, immediately upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union, of which both Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine had been formally founding constituent republics, bilateral relations were revived. Relations between the two countries have been hostile since the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, followed by Russia's annexation of Crimea from Ukraine, and over Russia's backing for the separatists fighters of the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic in a war that by early 2020 had killed more than 13,000 people and brought Western sanctions on Russia.[1]

History[]

Interactions between Russia and Ukraine began on a formal basis from the 17th century (note the Treaty of Pereyaslav between Moscow and Bohdan Khmelnytsky's Cossacks in 1654), but international-level relations ceased when Catherine the Great liquidated the autonomy of the Cossack Hetmanate in 1764. The two states interacted again briefly after the communist 1917 October Revolution.

In 1920, Soviet Russian forces overran Ukraine and relations between the two states transitioned from international to internal ones within the Soviet Union, founded in 1922. After the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, Ukraine has undergone periods of ties, tensions, and outright hostility from Russia.

Before Euromaidan (2013–2014), under President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych (in office from February 2010 until he was removed from power on 22 February 2014[2]), relations were cooperative, with various trade agreements in place.[3][4][5][6]

On 1 March 2014, the Federation Council of the Russian Federal Assembly voted unanimously to allow the President of Russia to enter the Russian Armed Forces on Ukrainian territory.[7][8][9] On March 3rd 2014, the Russian representative to the United Nations, Vitaly Churkin, presented a letter from March 1st signed by former Ukrainian President Yanukovych and addressed to President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin. The letter was a request for Russian Armed Forces to enter Ukraine territory.[10]

During the February–March 2014 Crimean crisis, Ukraine lost control of its government buildings, airports and military bases in Crimea to unmarked soldiers and local pro-Russian militias.[2] This started on February 27th when unmarked armed men seized the Crimean parliamentary building.[2] The same day the Crimean parliament replaced the local government with one that wanted Crimean unification with Russia.[11][12] This government organized the 2014 Crimean status referendum on March 14th in which the voters voted overwhelmingly to join Russia.[13] On March 17th, Crimea declared its independence.[14] On March 18th, a treaty on incorporating Crimea and Sevastopol into Russia was signed in Moscow and in five days the "Constitutional Law on admitting to the Russian Federation the Republic of Crimea and establishing within the Russian Federation the New Constituent Entities the Republic of Crimea and the City of Federal Importance Sevastopol" was quickly pushed through the Russian parliament, signed by the Russian President, and entered into force.[15] By March 19th, all Armed Forces of Ukraine were withdrawn from Crimea.[16] On April 17th, President Putin stated that the Russian military had backed Crimean separatist militias, stating that Russia's intervention was necessary "to ensure proper conditions for the people of Crimea to be able to freely express their will".[17]

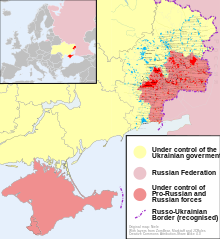

Throughout March and April 2014, pro-Russian unrest spread in Ukraine, with pro-Russian groups proclaiming "People's Republics" in the oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk, as of 2017 both partially outside the control of the Ukrainian government. In response, Ukraine initiated multiple international-court litigations against Russia, as well as suspending all types of military cooperation and military exports.[18] Many countries and international organizations applied sanctions against the Russian Federation and against Ukrainian citizens involved in and responsible for the escalation.

Military clashes between pro-Russian rebels (backed by Russian military) and the Ukrainian Armed Forces began in the east of Ukraine in April 2014. On 5 September 2014, the Ukrainian government and representatives of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic signed a tentative truce (ceasefire – the agreement).[19] The ceasefire imploded amidst intense new fighting in January 2015. A new ceasefire agreement has operated since mid-February 2015, but this agreement also failed to stop the fighting.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] In January 2018, the Verkhovna Rada passed a law defining areas seized by the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic as "temporarily occupied by Russia", the law also called Russia an "aggressor" state.[27] Russia has been accused by NATO and Ukraine of engaging in direct military operations to support the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic.[28] Russia denies this,[28] but in December 2015, Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin admitted that Russian military intelligence officers were operating in Ukraine, insisting though that they were not the same as regular troops.[29] Russia has admitted that Russian "volunteers" are helping the separatists People's Republics.[27]

On 10 February 2015, in response to Russian military intervention, the Ukrainian parliament registered a draft decree on suspending diplomatic relations with Russian Federation.[30] Although this suspension did not materialize, Ukrainian official Dmytro Kuleba (Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the Council of Europe) acknowledged early April 2016 that diplomatic relations had been reduced "almost to zero".[31] In late 2017, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin stated that "there are no diplomatic relations with Russia in terms of content".[32]

On 5 October 2016, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine officially recommended that its citizens avoid any type of travel to Russia or transit through its territory. The Ministry cited Russian law enforcers' growing number of groundless arrests of Ukrainian citizens who are allegedly often "rudely treated using illegal methods of physical and psychological pressure, torture and other acts violating human rights and dignity".[33]

In March 2014 Ukraine started to ban several Russian TV channel from broadcast in Ukraine,[34][35][36][nb 1] followed in February 2015 with a ban on showing (on Ukrainian television) of "audiovisual works" that contain "the popularization, agitation for, propaganda of any action of law enforcement agencies, the armed forces, other armed, military or security forces of the occupier state".[36][38] One year later Russian productions (on Ukrainian television) had decreased by 3 to 4 (times).[38] In 2015 Ukraine started banning Russian artists from entering Ukraine and banning other Russian works of culture from the country also when they were considered "a threat to national security".[39] (Following the Kerch Strait incident) starting 30 November, Ukraine is banning all Russian men between 16 and 60 from entering the country with exceptions for humanitarian purposes,[40] claiming this is a security measure.[41][42][43] As another response to the Kerch Strait incident Ukraine imposed a 30-day martial law period that started on 26 November in 10 Ukrainian border oblasts (regions).[44] Martial law was introduced because Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko claimed there was a threat of "full-scale war" with Russia.[44]

Russia has an embassy in Kyiv and consulates in Kharkiv, Lviv, and Odessa. Ukraine has an embassy in Moscow and consulates in Rostov-on-Don, Saint Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, Tyumen and Vladivostok. Ukraine recalled its ambassador to Russia Volodymyr Yelchenko in March 2014.[45] Since then, Ukraine's highest diplomatic representation in Russia has been its temporary chargé d'affaires.[46] Similarly, since July 2016, after the Russian ambassador to Ukraine Mikhail Zurabov was relieved, Russia's highest diplomatic representation in Ukraine has also been its temporary chargé d'affaires.[46]

Some[quantify] analysts[which?] believe that the current Russian leadership is determined to prevent an equivalent of the Ukrainian Orange Revolution in Russia. This perspective is supposed[by whom?] to explain not only Russian domestic policy but also Moscow's sensitivity to events abroad.[47] Many[quantify] in Ukraine and beyond[where?] believe that Russia has periodically used its vast energy resources to bully its smaller neighbours, but the Russian government argues that internal squabbling amongst Ukraine's political elite caused energy-supply disputes.[48] The conflict in Ukraine and the alleged role of Russia in it greatly escalated tensions in the relationship between Russia and major Western powers, especially relations between Russia and the United States. The situation caused some observers to characterize frostiness in 2014 as assuming an adversarial nature, or presaging the advent of Cold War II and World War III.[49][50][51]

Country comparison[]

| Russia | Ukraine | |

|---|---|---|

| Coat of arms |

|

|

| Flag |

|

|

| Population | 146267288[when?][citation needed] | 42539010[when?][citation needed] |

| Area | 17098246 km2 (6601670 sq mi)[citation needed] | 603700 km2 (233100 sq mi)[citation needed] |

| Population density | 8/km2 (21/sq mi) | 73.8/km2 (191/sq mi) |

| Time zones | 9 | 1 |

| Exclusive economic zone | 8095881 km2 (3125837 sq mi) | 147318 km2 (56880 sq mi) |

| Capital | Moscow | Kyiv |

| Largest city | Moscow (pop. 12197596, 20004462 Metro) | Kyiv (pop. 2900920, 3375000 Metro) |

| Government | Federal semi-presidential constitutional republic |

Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

| Official language | Russian (de facto and de jure) | Ukrainian (de facto and de jure) |

| Main religions | 71% Orthodox[52] 13% non-religious 10% Islam 1% unaffiliated Christian 2% other Orthodox 1% other religions (2017 Census) |

60.7% Christianity[citation needed] 35.2% non-Religious 0.6% Islam 3.3% other |

| Ethnic group | 80.90% Russians 8.75% Turkic peoples 3.96% other Indo-Europeans (2.03% Ukrainians) 3.78% Caucasians 1.76% Finno-Ugric and Mongolian peoples and others |

77.8% Ukrainians 17.3% Russians 4.9% others/unspecified |

| GDP (nominal) by the IMF | $1576 billion[53] | $126 billion[53] |

| GDP (PPP) by the IMF | $4168 billion[54] | $389 billion[54] |

| GDP (nominal) per capita by the IMF | $10,955 | $2,583 |

| GDP (PPP) per capita by the IMF | $27,890 | $8,656 |

| Army size | Russian Ground Forces (2018) (including reserves)[55]

|

Ukrainian Ground Forces (2018) (including reserves)[56]

|

| Navy size | Russian Navy (2018)[55]

Total naval strength: 324 ships (Reserves not included)

|

Ukrainian Navy (2020)[56]

Total naval strength: 36 ships (Reserves not included)

|

| Air Force size | Russian Air Force (2018)[55]

|

Ukrainian Air Force (2018)[56]

|

| Current President | Vladimir Putin | Volodymyr Zelensky |

| Current Prime Minister | Mikhail Mishustin | Denys Shmyhal |

| Nuclear warheads

active/total |

1,600 / 6,850 (2019) | 0 / 0 (2019) |

History of relations[]

Kyivan Rus'[]

Both like Russia as well as Ukraine claim their heritage from Rus (also known as Kyivan Rus or Ancient Rus) that in the 10th century united several tribes and clans of various ethnic origin and background under the Byzantine church. Rus as a political formation suffered from feudal fragmentation, according to the Great Soviet Encyclopedia and its history is filled with numerous conflicts between various princes. According to old-Russian chronicles, Kyiv, the modern capital of Ukraine, was proclaimed as the mother of Rus (Russian/Ruthenian) cities owing to the once powerful later Medieval state, a predecessor of both Russian and Ukrainian nations.[57] The phrase "mother of cities" is of Greek origin that means metropolis. Discourse on the subject of origin of both Russians and Ukrainians could lead to heated arguments.

Muscovy and the Russian Empire[]

After the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus' the histories of the Russian and Ukrainian people's started to diverge.[58] The former, having successfully united all the remnants of the Rus' northern provinces, swelled into a powerful Russian state. The latter came under the domination of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, followed by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Within the Commonwealth, the militant Zaporozhian Cossacks refused polonization, and often clashed with the Commonwealth government, controlled by the Polish nobility. Unrest among the Cossacks caused them to rebel against the Commonwealth and seek union with Russia, with which they shared much of the culture, language and religion, which was eventually formalized through the Treaty of Pereyaslav in 1654.[59] From the mid-17th century Ukraine was gradually absorbed into the Russian Empire, which was completed in the late 18th century with the Partitions of Poland. Soon afterward in the late 18th century the Cossack host was forcibly disbanded by the Empire, with most of the population relocated to the Kuban region in the South edge of the Russian Empire, where the Cossacks would serve a valuable role for the Empire in subjugating the fierce Caucasian tribes.

The Russian Empire considered Ukrainians (and Belarusians) a part of the Russian identity and referred to them as "Little Russians".[60] Until the end of World War I this view was opposed by a small group of Ukrainian nationalists.[61] Nevertheless, a perceived threat of "Ukrainian separatism" set in motion a set of measures aimed at the russification of the "Little Russians".[61] In 1804 the Ukrainian language as a subject and language of instruction was banned from schools.[62] In 1876 followed by a ban on Ukrainian books by Alexander II's secret Ems Ukaz, which prohibited publication and importation of most Ukrainian-language books, public performances and lectures, and even banned the printing of Ukrainian texts accompanying musical scores.[63]

Soviet Union[]

The February Revolution saw establishment of official relations between the Russian Provisional Government and the Ukrainian Central Rada that was represented at the Russian government by its commissar Petro Stebnytsky. At the same time Dmitry Odinets was appointed the representative of Russian Affairs in the Ukrainian government. After the Soviet military aggression by the Soviet government at the beginning of 1918, Ukraine declared its full independence from the Russian Republic. The two treaties of Brest-Litovsk that Ukraine and Russia signed separately with the Central Powers calmed the military conflict between them and peace negotiations were initiated the same year.

After the end of World War I, Ukraine became a battleground in the Russian Civil War and both Russians and Ukrainians fought in nearly all armies based on their political beliefs.[nb 2]

In 1922, Ukraine and Russia were two of the founding members of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and were the signatories of the treaty that terminated the union in December 1991.[nb 3]

The end of the Russian Empire also ended the ban on the Ukrainian language.[62] Followed by a period of korenizatsiya that promoted the cultures of the different Soviet Republics.[64]

In 1932–1933 Ukraine experienced the Holodomor (Ukrainian: Голодомор, "Extermination by hunger" or "Hunger-extermination"; derived from 'Морити голодом', "Killing by Starvation") which was a man-made famine in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic that killed up to 7.5 million Ukrainians. During the famine, which is also known as the "Terror-Famine in Ukraine" and "Famine-Genocide in Ukraine", millions of citizens of the Ukrainian SSR, the majority of whom were Ukrainians, died of starvation in a peacetime catastrophe unprecedented in the history of Ukraine. Scholars disagree on the relative importance of natural factors and bad economic policies as causes of the famine and the degree to which the destruction of the Ukrainian peasantry was premeditated on the part of Soviet leadership. The Holodomor famine extended to many Soviet republics, including Russia and Kazakhstan. In the absence of absolute documentary proof of intent, scholars have also made the argument that the Holodomor was ultimately a consequence of the economic problems associated with radical economic changes implemented during the period of liquidation of private property and Soviet industrialization, combined with the widespread drought of the early 1930s.

On 13 January 2010, Kyiv Appellate Court posthumously found Stalin, Kaganovich, Molotov, and the Ukrainian Soviet leaders Kosior and Chubar, amongst other functionaries guilty of genocide against Ukrainians during the Holodomor famine.[65]

Flag of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1954–1991)

Flag of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1950–1991)

Russian SFSR |

Ukrainian SSR |

|---|---|

Independent Ukraine[]

1990s[]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine held almost 5,000 nuclear weapons, about one third of the Soviet nuclear arsenal and the third largest in the world at the time, as well as significant means of its design and production.[66][67] 130 UR-100N intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) with six warheads each, 46 RT-23 Molodets ICBMs with ten warheads apiece, as well as 33 heavy bombers, totaling approximately 1,700 warheads remained on Ukrainian territory.[68] While Ukraine had physical control of the weapons, it did not have operational control, as they were dependent on Russian-controlled electronic Permissive Action Links and the Russian command and control system. In 1992, Ukraine agreed to voluntarily remove over 3,000 tactical nuclear weapons.[66] Following the signing of the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances among the U.S., the U.K., and Russia, as well as similar agreements with France and China, Ukraine agreed to destroy the rest of its nuclear weapons, and to join the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).[69][70][71]

Additionally, several acute disputes formed between the two countries. The first was the question of the Crimea which the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic had administered since 1954. This however was largely resolved in an agreement that allowed for Crimea to remain part of Ukraine, provided its Autonomous Republic status is preserved.

The second major dispute of the 1990s was the city of Sevastopol, with its base of the Black Sea Fleet. During the fall of the Soviet state the city along with the rest of Ukraine participated in the national referendum for independence of Ukraine where 57.07% of the turnout voted for the succession of the city in favour of the Ukrainian state, yet the Supreme Soviet of Russia voted to reclaim the city as its territory in 1993. After several years of intense negotiations, in 1997 the whole issue was resolved by partitioning the Black Sea Fleet and leasing some of the naval bases in Sevastopol to the Russian Navy until 2017. In 1997 the Friendship Treaty, which fixed the principle of strategic partnership, the recognition of the inviolability of existing borders, respect for territorial integrity and mutual commitment not to use its territory to harm the security of each other, was signed.[72][73]

Another major dispute was related to the energy supplies, as several Soviet—Western Europe oil and gas pipelines ran through Ukraine. Later after new treaties came into effect, Ukraine's gas debt arrears to Russia were paid off by transfer of some nuclear-capable weapons that Ukraine inherited from the USSR, to Russia such as the Tu-160 strategic bombers.[74] During the 1990s both countries along with other ex-Soviet states founded the Commonwealth of Independent States and large business partnerships came into effect.

While the Russian share in Ukraine's exports declined from 26.2 percent in 1997 to around 23 percent in 1998–2000, the share of imports held steady at 45–50 percent of the total. Overall, between one third and one half of Ukraine's trade was with the Russian Federation. Dependence was particularly strong in energy. Up to 70–75 percent of annually consumed gas and close to 80 percent of oil came from Russia. On the export side, too, dependence was significant. Russia remained Ukraine's primary market for ferrous metals, steel plate and pipes, electric machinery, machine tools and equipment, food, and products of chemical industry. It has been a market of hope for Ukraine's high value-added goods, more than nine tenths of which were historically tied to the Russian consumer. Old buyers gone by 1997, Ukraine had experienced a 97–99 percent drop in production of industrial machines with digital control systems, television sets, tape recorders, excavators, cars and trucks. At the same time, and in spite of the postcommunist slowdown, Russia came out as the fourth-largest investor in the Ukrainian economy after the US, the Netherlands, and Germany, having contributed $150.6 million out of $2.047 billion in foreign direct investment that Ukraine had received from all sources by 1998.[75]

2000s[]

Although disputes prior to the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election were present including the speculations regarding accidental shooting down of a Russian airliner by the Ukrainian military and the controversy with the Tuzla Island, relations with Russia under the latter years of Leonid Kuchma improved. In 2002, the Russian Government participated in financing the construction of the Khmelnytskyi and the Rivne Nuclear Power Plants.[76] However, after the Orange Revolution several problems resurfaced including the Russia–Ukraine gas disputes, and Ukraine's bid to join NATO.

The overall perception of relations with Russia in Ukraine differs largely on regional factors. Many Russophone eastern and southern regions, which are also home to the majority of the Russian diaspora in Ukraine welcome closer relations with Russia.[77] However further central and particularly western regions (who were never a part of Imperial Russia) of Ukraine show a less friendly attitude to the idea of a historic link to Russia[78][79][80][81] and the Soviet Union in particular.[82]

Russia has no intention of annexing any country.

Russian President Putin (24 December 2004)[83]

In Russia, there is[when?] no regional breakdown in the opinion of Ukraine,[84] but on the whole, Ukraine's recent attempts to join the EU and NATO were seen as change of course to only a pro-Western, anti-Russian orientation of Ukraine and thus a sign of hostility and this resulted in a drop of Ukraine's perception in Russia[85] (although President of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko reassured Russia that joining NATO was not meant as an anti-Russian act,[86] and Putin said that Russia would welcome Ukraine's membership in the EU[87]). This was further fuelled by the public discussion in Ukraine of whether the Russian language should be given official status[88] and be made the second state language.[89][90] During the 2009 gas conflict the Russian media almost uniformly portrayed Ukraine as an aggressive and greedy state that wanted to ally with Russia's enemies and exploit cheap Russian gas.[91]

Further worsening of relations was provoked by belligerent statements made in 2007–2008 by both Russian (e.g. the Russian Foreign Ministry,[92] the Mayor of Moscow Yury Luzhkov[93] and then President Vladimir Putin[86][94]) and Ukrainian politicians, for example, the former Foreign Minister Borys Tarasiuk,[95] deputy Justice Minister of Ukraine [96] and then leader of parliamentary opposition Yulia Tymoshenko.[97]

The status of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol remained a matter of disagreement and tensions.[84][98]

Second Tymoshenko government[]

In February 2008 Russia unilaterally withdrew from the Ukrainian–Russian intergovernmental agreement on SPRN signed in 1997.[99]

During the Russo-Georgian War, relations between Ukraine and Russia soured, due to Ukraine's support and selling of arms to Georgia. According to a Russian Investigative Committee 200 members of the Ukrainian UNA-UNSO and "full-time servicemen of the Ukrainian army" aided Georgian forces during the fighting. Ukraine denied the accusation.[citation needed] Further disagreements over the position on Georgia and relations with Russia were among the issues that brought down the Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc + Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko coalition in the Ukrainian parliament during September 2008[100] (on 16 December 2008 the coalition did remerge with a new coalition partner, the Lytvyn Bloc[101]).

During the 2008 South Ossetia war, relations with Russia also deteriorated over the new Ukrainian regulations for the Russian Black Sea Fleet such as the demand that Russia obtain prior permission when crossing the Ukrainian border, which Russia refused to comply with.[102][103]

On 2 October 2008, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin accused Ukraine of supplying arms to Georgia during the South Ossetia War. Putin also claimed that Moscow had evidence proving that Ukrainian military experts were present in the conflict zone during the war. Ukraine has denied the allegations. The head of its state arms export company, Ukrspetsexport, said no arms were sold during the war, and Defense Minister Yuriy Yekhanurov denied that Ukraine's military personnel fought on the side of Georgia.[104] Prosecutor General of Ukraine Oleksandr Medvedko confirmed on 25 September 2009 that there was no personnel of the Ukrainian Armed Forces participated in the 2008 South Ossetia War, no weapons or military equipment of the Ukrainian Armed Forces were present at the conflict, and no help was given to the Georgian side. Also in the declaration the Ukrainian officials informed that the international transfers of the military specialization equipment between Ukraine and Georgia during the 2006–2008 were conducted in accordance with the earlier established contracts, the laws of Ukraine, and the international treaties.[105]

The US supported Ukraine's bid to join NATO launched in January 2008 as an effort to obtain the NATO Membership Action Plan.[106][107][108] Russia strongly opposed any prospect of Ukraine and Georgia becoming NATO members.[nb 4][109][110][111] According to the alleged transcript of Putin's speech at the 2008 NATO–Russia Council Summit in Bucharest, Putin spoke of Russia's responsibility for ethnic Russians resident in Ukraine and urged his NATO partners to act advisedly; according to some media reports he then also privately hinted to his US counterpart at the possibility of Ukraine losing its integrity in the event of its NATO accession.[112] According to a document in the United States diplomatic cables leak Putin "implicitly challenged the territorial integrity of Ukraine, suggesting that Ukraine was an artificial creation sewn together from territory of Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania, and especially Russia in the aftermath of the Second World War."[113]

During a January 2009 dispute over natural gas prices, exports of Russian natural gas through Ukraine were shut.[114] Relations further deteriorated when Russian Prime Minister Putin during this dispute said that "Ukrainian political leadership is demonstrating its inability to solve economic problems, and [...] situation highlights the high criminalization of [Ukrainian] authorities"[115][116] and when in February 2009 (after the conflict) Ukrainian President Yushchenko[117][118] and the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry considered Russian President Dmitry Medvedev's statement that Ukraine must compensate for gas crisis losses to the European countries an "emotional statement which is unfriendly and hostile towards Ukraine and the EU member-states".[119][120] During the conflict the Russian media almost uniformly portrayed Ukraine as an aggressive and greedy state that wanted to ally with Russia's enemies and exploit cheap Russian gas.[91]

After a "master plan" to modernize the natural gas infrastructure of Ukraine between the EU and Ukraine was announced (on 23 March 2009) Russian Energy Minister Sergei Shmatko told an investment conference at which the plan was unveiled that it appeared to draw Ukraine legally closer to the European Union and might harm Moscow's interests.[121] According to Putin "to discuss such issues without the basic supplier is simply not serious".[121]

In a leaked US diplomatic cable (as revealed by WikiLeaks) regarding the January 2009 Russian–Ukrainian gas crisis, the US Ambassador to Ukraine William Taylor was quoting Ambassador of Ukraine to Russia Kostyantyn Hryshchenko as expressing his opinion that Kremlin leaders wanted to see a totally subservient person in charge in Kyiv (a regency in Ukraine) and that Putin "hated" the then-President Yushchenko and had a low personal regard for Yanukovych, but saw then-Prime Minister Tymoshenko as someone perhaps not that he can trust, yet with whom he could deal.[122]

On 11 August 2009, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev posted a videoblog on the Kremlin.ru website, and the official Kremlin LiveJournal blog, in which he criticised Yushchenko for what Medvedev claimed was the Ukrainian president's responsibility in the souring of Russia–Ukraine relations and "the anti-Russian position of the current Ukrainian authorities".[nb 5] Medvedev further announced that he would not send a new ambassador to Ukraine until there was an improvement in the relationship.[123][124][nb 6][125] In response, Yushchenko wrote a letter which noted he could not agree that the Ukrainian–Russian relations had run into problems and wondered why the Russian president completely ruled out the Russian responsibility for this.[126][127][nb 7] Analysts said Medvedev's message was timed to influence the campaign for the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election.[123][129] The U.S. Department of State spokesman, commenting on the message by Medvedev to his Ukrainian counterpart Yuschenko, said, among other things: "It is important for Ukraine and Russia to have a constructive relationship. I'm not sure that these comments are necessarily in that vein. But going forward, Ukraine has a right to make its own choices, and we feel that it has a right to join NATO if it chooses."[130]

On 7 October 2009, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said the Russian government wanted to see economy prevail in Russian–Ukrainian relations and that relations between the two countries would improve if the two countries set up joint ventures, especially in small and medium-sized businesses.[131] At the same meeting in Kharkiv, Lavrov said the Russian government would not respond to a Ukrainian proposal to organize a meeting between the Russian and Ukrainian presidents,[132] but that "Contacts between the two countries' foreign ministries are being maintained permanently."[133]

On 2 December 2009, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Petro Poroshenko and Lavrov agreed on gradually abandoning the compilation of lists of individuals banned from entering their countries.[134]

2010s[]

Viktor Yanukovych presidency[]

According to Taras Kuzio, Viktor Yanukovych was the most pro-Russian and neo-Soviet[clarification needed] president to have been elected in Ukraine.[3] Since his election he fulfilled all of the demands laid out by Russian President Dmitri Medvedev in his letter written to former President Viktor Yushchenko in August 2009.[3]

On 22 April 2010 Presidents Viktor Yanukovych and Dmitry Medvedev signed an agreement concerning renting of the Russian Naval Forces base in Sevastopol in the next 25 years for the natural gas discounts in deliveries which accounted for $100 per each 1,000 cubic meters.[135][136][137] The lease extension agreement was highly controversial in and outside of Ukraine.[3]

On 17 May 2010, the President Dmitry Medvedev arrived in Kyiv on a two-day visit.[138] During the visit Medvedev hoped to sign cooperation agreements in "inter-regional and international problems", according to RIA Novosti. That also was mentioned on the official inquiry at the Verkhovna Rada by the First Vice Prime Minister Andriy Klyuyev. According to some news agencies the main purpose of the visit was to solve the disagreements in the Russian–Ukrainian energy relations after Viktor Yanukovych agreed on the partial merger of Gazprom and Naftogaz.[139] Apart from the merger of the state gas companies there are also talks of the merger of the nuclear energy sector as well.[140]

Both Russian President Dmitry Medvedev (April 2010[4]) and Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin (June 2010[5]) have stated they noticed a big improvement in relations since Viktor Yanukovych presidency.

On 14 May 2013 an unknown veteran of unknown intelligence service Sergei Razumovsky, leader of the All-Ukrainian Association of Homeless Officers, who resides in Ukraine under the Ukrainian flag calls on creation of Ukrainian–Russian international volunteer brigades in support of the Bashar al-Assad government in Syria to fight rebels.[141][142][143] One of the reasons why Rozumovsky wants to create such brigades is the fact that government of Ukraine does not support its officer corps.[144] Because of that Rozumovsky has intentions to apply for citizenship of Syria.[145] Some sources claim that he is a Kremlin's provocateur.[146]

On 17 July 2013 near the Russian coast of the Sea of Azov which is considered as internal waters of both Russia and Ukraine (no boundary delimitation), the Russian coast guard patrol boat collided with a Ukrainian fishing vessel.[147] Four fishermen died[148] while one was detained by Russian authorities on the charges of poaching.[149] According to the surviving fisherman, their boat was rammed by Russians[150] and the fishermen were fired at as well, while the Russian law enforcement agency claimed that it was the poachers who tried to ram into the patrol vessel.[151] The Minister of Justice of Ukraine Olena Lukash acknowledged that Russia has no jurisdiction to prosecute the detained citizen of Ukraine.[152] According to the wife of the surviving fisherman, the Ukrainian Consul in Russia was very passive in providing any support on the matter.[153] The surviving fisherman was expected to be released to Ukraine before 12 August 2013, however, the Prosecutor Office of Russia chose to keep the Ukrainian detained in Russia.[154]

On 14 August 2013 the Russian Custom Service stopped all goods coming from Ukraine.[155] Some politicians saw that as start of a trade war against Ukraine to prevent Ukraine from signing a trade agreement with the European Union.[156] According to Pavlo Klimkin, one of the Ukrainian negotiators of the Association Agreement, initially "the Russians simply did not believe (the association agreement with the EU) could come true. They didn't believe in our ability to negotiate a good agreement and didn't believe in our commitment to implement a good agreement."[157]

Another incident took place on the border between Belgorod and Luhansk oblasts when an apparently inebriated Russian tractor driver decided to cross the border to Ukraine along with his two friends on 28 August 2013.[158][159] Unlike the Azov incident that took place a month earlier on 17 July 2013, the State Border Service of Ukraine handed over the citizens of Russia right back to the Russian authorities. Tractor Belarus was taken away and handed over to the Ministry of Revenues and Duties.

In August 2013 Ukraine become an observer of the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia.[160]

Euromaidan and aftermath[]

On 17 December 2013 Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to lend Ukraine 15 billion dollars in financial aid and a 33% discount on natural gas prices.[161][162] The treaty was signed amid massive, ongoing protests in Ukraine for closer ties between Ukraine and the European Union.[163] Critics pointed out that in the months before the 17 December 2013 deal a change in Russian customs regulations on imports from Ukraine was a Russian attempt to prevent Ukraine to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union.[164][165][161]

The 2014 Crimean crisis was unfolding in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, in the aftermath of the February 2014 Ukrainian revolution, in which the government of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was ousted. Protests were staged by groups of mainly ethnic Russians who opposed the events in Kyiv and wanted close ties or integration with Russia, in addition to expanded autonomy or possible independence for Crimea. Other groups, including Crimean Tatars, protested in support of the revolution. On 27 February, unmarked military men wearing masks seized a number of important buildings in Crimea, including the parliament building and two airports.[2] Under siege, the Supreme Council of Crimea dismissed the autonomous republic's government and replaced chairman of the Council of Ministers of Crimea, Anatolii Mohyliov with Sergey Aksyonov.[2]

Ukraine accused Russia of intervening in Ukraine's internal affairs, while the Russian side officially denied such claims. In response to the crisis, the Ukrainian parliament requested that the Budapest Memorandum's signatories reaffirm their commitment to the principles enshrined in the political agreement, and further asked that they hold consultations with Ukraine to ease tensions.[166] On 1 March without declaration of war, the Russian parliament granted President Vladimir Putin the authority to use military force in Ukraine.[167] On the same day, the acting president of Ukraine, Oleksandr Turchynov decreed the appointment of the Prime Minister of Crimea as unconstitutional. He said, "We consider the behavior of the Russian Federation to be direct aggression against the sovereignty of Ukraine!"

On 11 March, the Crimean parliament voted and approved a declaration on the independence of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol from Ukraine, as the Republic of Crimea, with 78 votes out of 100 in favor.[168] Crimeans voted in a referendum to rejoin Russia on 16 March.[169][170] The Republic of Crimea declared its independence from Ukraine the next day, started seeking UN recognition, and requested to join the Russian Federation.[14] On the same day, Russia recognized Crimea as a sovereign state.[171][172] On 19 March 2014 all Ukrainian Armed Forces (at the time besieged in their bases by unmarked soldiers) were withdrawn from Crimea.[16] On 8 April 2014 an agreement was reached between Russia and Ukraine to return interned vessels to Ukraine and "for the withdrawal of an undisclosed number of Ukrainian aircraft seized in Crimea".[173] Russia returned 35 ships that had been impounded during its annexation of Crimea but unilaterally suspended the return of Ukrainian Navy materials from Crimea to Ukraine proper because/after Ukraine did not renew its unilaterally declared ceasefire on 1 July 2014 in the War in Donbass.[174][175] 16 minor ships are hence yet to return to Ukraine proper.[175]

Immediately after the announcement of Russian recognition of Crimea as a sovereign state, Ukraine responded with sanctions against Russia as well as blacklisting and freezing assets of numerous individuals and entities involved with the annexation. Ukraine announced to not buy Russian products. Other countries supporting Ukraine's position (e.g. the European Union, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Albania, Montenegro, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, etc.) followed similar measures.[176] Russia responded with similar measures against Ukraine and its supporters but did not publicly reveal the list of people or entities sanctioned.[177][178][179]

On 27 March, the U.N. General Assembly passed a non-binding Resolution 68/262 that declared the Crimean referendum invalid.[180][181] Also on March 27, 2016, Dmitry Kozak was appointed to greatly strengthen Crimea's social, political, and economic ties to Russia.[182][183]

On 14 April, Russian President Putin announced that he would open a ruble-only account with Bank Rossiya and would make it the primary bank in the newly annexed Crimea as well as giving the right to service payments on Russia's $36 billion wholesale electricity market—which gave the bank $112 million annually from commission charges alone.[184]

On 17 April 2014, President Putin stated that the Russian military had backed Crimean separatist militias, stating that Russia's intervention was necessary "to ensure proper conditions for the people of Crimea to be able to freely express their will".[17]

Throughout March and April 2014, pro-Russian unrest spread in Ukraine, with pro-Russian groups proclaiming "People's Republics" in the oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk, as of 2017 both partially outside the control of the Ukrainian government.[18]

Military clashes between pro-Russian rebels (backed by Russian military) and the Armed Forces of Ukraine began in the Donbass region in April 2014. On 5 September 2014 the Ukrainian government and representatives of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic signed a tentative truce (ceasefire – the agreement).[19] The ceasefire imploded amidst intense new fighting in January 2015. A new ceasefire agreement has operated since mid-February 2015, but this agreement also failed to stop the fighting.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] Russia has been accused by NATO and Ukraine of engaging in direct military operations to support the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic.[28] Russia denies this,[28] but in December 2015, Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin admitted that Russian military intelligence officers were operating in Ukraine, insisting though that they were not the same as regular troops.[29] Russia has admitted that Russian "volunteers" are helping the separatists People's Republics.[27]

At the 26 June 2014 session of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko stated that bilateral relations with Russia cannot be normalized unless Russia undoes its unilateral annexation of Crimea and returns its control of Crimea to Ukraine.[185] In February 2015, Ukraine ended a 1997 agreement that Russians can enter Ukraine with internal ID instead of a travel passport.[186]

Early March 2014, and prior to its independence referendum, all broadcast of Ukraine-based TV channels was suspended in Crimea.[37] Later that month, the Ukrainian National Council for TV and Radio Broadcasting ordered measures against some Russian TV channels which were accused of broadcasting misleading information about Ukraine.[34][35] In February 2015 the law "On protection information television and radio space of Ukraine," banned the showing (on Ukrainian television) of "audiovisual works" that contain "the popularization, agitation for, propaganda of any action of law enforcement agencies, the armed forces, other armed, military or security forces of the occupier state" was enacted.[38] One year later Russian productions (on Ukrainian television) had decreased by 3 to 4 (times).[38] 15 more Russian TV channels were banned in March 2016.[36]

Continued deterioration of relations[]

In May 2015, Ukraine suspended military cooperation agreement with Russia,[187][188] that was in place since 1993.[189] Following a breakdown in mutual business ties, Ukraine also ceased supply of components that were used in production of military equipment by Russia.[190] In August, Russia announced that it will ban import of Ukrainian agricultural goods from January 2016.[191] In October 2015, Ukraine banned all direct flights between Ukraine and Russia.[192] In November 2015, Ukraine closed its air space to all Russian military and civil airplanes.[193] In December 2015, Ukrainian lawmakers voted to place a trade embargo on Russia in retaliation of the latter's cancellation of the two countries free-trade zone and ban on food imports as the free-trade agreement between the European Union and Ukraine is to come into force in January 2016.[194] Russia imposes tariffs on Ukrainian goods from January 2016, as Ukraine joins the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the EU.[195]

Since 2015 Ukraine is banning Russian artists from entering Ukraine and also banning other Russian works of culture from Russia when they were considered "a threat to national security".[39] Russia did not reciprocate, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov responded by saying that "Moscow should not be like Kyiv" and should not impose "black lists" and restrictions on the cultural figures of Ukraine.[196] Lavrov did add that Russian producers and the film industry should take into account "unfriendly attacks of foreign performers in Russia" when implementing cultural projects with them.[196]

According to the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine the amount of Russian citizens who crossed the Russia–Ukraine border (more than 2.5 million Russians in 2014) dropped by almost 50% in 2015.[197]

On 5 October 2016, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine officially recommended that its citizens should avoid travel to Russia claiming Russian law enforcers growing number of groundless arrests of Ukrainian citizens and that they often "rudely treat Ukrainians, use illegal methods of physical and psychological pressure, torture and other acts that violate human dignity".[33] In a 14 June 2018 resolution on Russia the European Parliament claimed there were 71 "illegally detained Ukrainian citizens in Russia and on the Crimean peninsula."[198]

Ukraine's 2017 education law makes Ukrainian the only language of primary education in state schools.[199] The law faced criticism from officials in Russia and Hungary.[200][201] Russia's Foreign Ministry stated that the law is designed to "forcefully establish a mono-ethnic language regime in a multinational state."[200]

On 18 January 2018 the Ukrainian parliament passed a law defining areas seized by the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic as "temporarily occupied by Russia."[27] The law also called Russia an "aggressor" state.[27]

In March 2018, the Ukrainian border guards detained in the Sea of Azov the Russian-flagged, Crimean-registered fishing vessel Nord, accusing the crew of entering "territory, which has been under a temporary occupation".[202] The captain of the Nord, Vladimir Gorbenko, is facing up to five years in prison.[203]

In November 2018 Russia fired upon and seized three Ukrainian Navy vessels (and imprisoned its 24 sailors in Moscow[204]) off the coast of Crimea injuring crew members.[205] The event prompted angry protests outside the Russian embassy in Ukraine and an embassy car was set on fire.[206] Consequently, martial law was imposed for a 30-day period from 26 November in 10 Ukrainian border oblasts (regions).[44] Martial law was introduced because Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko claimed there was a threat of "full-scale war" with Russia.[44] During the martial law (and starting on 30 November 2018) Ukraine banned all Russian men between 16 and 60 from entering the country for the period of the martial law with exceptions for humanitarian purposes.[40] Ukraine claimed this was a security measure to prevent Russia from forming units of “private” armies on Ukrainian soil.[41] On 27 December 2018 the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine announced that it had extended "the restrictive measures of the State Border Guard Service regarding the entry of Russian men into Ukraine.”[43] (According to the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine) between 26 November and 26 December 2018 1,650 Russian citizens were refused entry into Ukraine.[207] From 26 December 2018 until 11 January 2019 the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine denied 800 Russian citizens access to Ukraine.[208]

Volodymyr Zelensky presidency[]

On 11 July 2019, recently elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky held a telephone conversation with Russian President Vladimir Putin following the former's appeals to the Russian leader to take part in talks with Ukraine, the United States, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom in Minsk.[209][210] The leaders also discussed the exchange of prisoners held by both sides.[210] On 7 September, Ukraine and Russia exchanged prisoners.[211]

Border[]

Russia and Ukraine share 2,295 kilometres (1,426 mi) of border. In 2014, the Ukrainian government unveiled a plan to build a defensive walled system along the border with Russia, named "Project Wall". It was expected to cost almost $520 million, take four years to complete and has been under construction as of 2015.[212] In June 2020 the State Border Guard of Ukraine expected that the project would be finished by 2025.[213]

On 1 January 2018 Ukraine introduced biometric controls for Russians entering the country.[214] On 22 March 2018 Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a decree that required Russian citizens and "individuals without citizenship, who come from migration risk countries” (more details were not given) to notify the Ukrainian authorities in advance about their reason for travelling to Ukraine.[214]

Since 30 November 2018 Ukraine bans all Russian men between 16 and 60 from entering the country with exceptions for humanitarian purposes.[40][43][208]

Armaments and aerospace industries[]

This section needs to be updated. (August 2016) |

The Ukrainian and Russian arms and aviation manufacturing sectors remained deeply integrated following the break-up of the Soviet Union. Ukraine is the world's eighth largest exporter of armaments according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, and according to analysts cited by The Washington Post around 70% of Ukraine's defence-related exports flowed to Russia before 2014, or nearly US$1 billion. Potentially strategically sensitive exports from Ukraine to Russia included 300–350 helicopter engines per year as well as various other aircraft engines from Motor Sich in Zaporizhia, intercontinental ballistic missiles from Yuzhmash in Dnipro, missile guidance systems from factories in Kharkiv, 20% of Russia's uranium consumption from mines in Zhovti Vody, 60% of the gears to be used in planned Russian warships from manufacturers Mykolaiv, and oil and gas from the Sea of Azov.[215]

In March 2014, during the 2014 Crimean crisis, Ukraine barred all exports of weaponry and military equipment to Russia.[216] Jane's Information Group believed (on 31 March 2014) that while supply may be slowed by the Ukrainian embargo, it was unlikely to do any real damage to Russia's military.[216]

Popular opinion[]

In Russia[]

In opinion polls, Russians generally say they have a more negative attitude towards Ukraine than vice versa. Polls in Russia have shown that after top Russian officials made radical statements or took drastic actions against Ukraine the attitude of those polled towards Ukraine worsened (every time). The issues that have hurt Russians' view of Ukraine are:

- Possible Ukrainian–NATO membership

- Ukrainian attempts to have the Holodomor recognized as genocide against the Ukrainian nation

- Attempts to honor the Ukrainian Insurgent Army

Although a large majority of Ukrainians voted for independence in December 1991, in the following years the Russian press portrayed Ukraine's independence as the work of "nationalists" who "twisted" the "correct" instincts of the masses according to a 1996 study.[217] The study argues that this influenced the Russian public to believe that the Ukrainian political elite is the only thing blocking the "Ukrainians' heartfelt wish" to reunite with Russia.[217] Some members of the Russian political elite continued to claim that Ukrainian is a Russian dialect and that Ukraine (and Belarus) should become part of the Russian Federation.[218] In a June 2010 interview Mikhail Zurabov, then Russian ambassador to Ukraine, stated "Russians and Ukrainians are a single nation with some nuances and peculiarities".[219] Ukrainian history is not treated as a separate subject in leading Russian universities but rather incorporated into the history of Russia.[220]

According to experts, the Russian government cultivates an image of Ukraine as the enemy to cover up its own internal mistakes.[citation needed] Analysts like Philip P. Pan (writing for The Washington Post) argued late 2009 that Russian media portrayed the then-Government of Ukraine as anti-Russian.[221]

| Opinion | October 2008[222] | April 2009[223] | June 2009[223] | September 2009[224] | November 2009[225] | September 2011[226] | February 2012[226] | May 2015[227] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | 38% | 41% | 34% | 46% | 46% | 68% | 64% | 26% |

| Negative | 53% | 49% | 56% | 44% | 44% | 25% | 25% | 59% |

80% had a "good or very good" attitude towards Belarus in 2009.[224]

During the 1990s, polls showed that a majority of people in Russia could not accept the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the independence of Ukraine.[228] According to a 2006 poll by VTsIOM 66% of all Russians regretted the collapse of the Soviet Union.[229] 50% of respondents in Ukraine in a similar poll held in February 2005 stated they regret the disintegration of the Soviet Union.[230] In 2005 (71%) and 2007 (48%) polls, Russians expressed a wish to unify with Ukraine; although a unification solely with Belarus was more popular.[231][232]

A poll released on 5 November 2009 showed that 55% of Russians believed that the relationship with Ukraine should be a friendship between "two independent states".[225] A late 2011 poll by the Levada Center showed 53% of polled Russians preferred friendship with an independent Ukraine, 33% preferred Ukraine to be under Russia's economic and political control, and 15% were undecided.[233] According to Levada's 2012 poll, 60% of Russians preferred Russia and Ukraine as independent but friendly states with open borders without visas or customs; the number of unification supporters increased by 4% to 20% in Russia.[234] Twenty surveys conducted from January 2009 to January 2015 by the Levada Center found that less than 10% of Russians supported Russia and Ukraine becoming one state.[235] In the January 2015 survey, 19% wanted eastern Ukraine to become part of Russia and 43% wanted it to become an independent state.[235]

A November 2014 survey by the University of Oslo found that most Russians viewed Ukraine as not legitimate as a state in its internationally recognised borders and with its then government.[236] According to an April 2015 survey by the Levada Center, when asked "What should be Russia's primary goals in its relations with vis-a-vis Ukraine?" (multiple answers allowed), the most common answers were: Restoring good neighborly relations (40%), retaining Crimea (26%), developing economic cooperation (21%), preventing Ukraine from joining NATO (20%), making gas prices for Ukraine the same as for other European countries (19%), and ousting the current Ukrainian leadership (16%).[237]

In Ukraine[]

| Opinion | October 2008[222] | June 2009[238] | September 2009[224] | November 2009[225] | September 2011[226] | January 2012[226] | April 2013[239] | Mar–Jun 2014[240] | June 2015[241] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | 88% | 91% | 93% | 96% | 80% | 86% | 70% | 35% | 21% |

| Negative | 9% | - | - | - | 13% | 9% | 12% | 60% | 72% |

A poll released on 5 November 2009 showed that about 67% of Ukrainians believed the relationship with Russia should be a friendship between "two independent states".[225] According to a 2012 poll by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), 72% of Ukrainians preferred Ukraine and Russia as independent but friendly states with open borders without visas or customs; the number of unification supporters shrunk by 2% to 14% in Ukraine.[234]

In December 2014, 85% of Ukrainians (81% in eastern regions) rated relations with Russia as hostile (56%) or tense (29%), according to a Deutsche Welle survey which did not include Crimea and the separatist-controlled part of Donbass.[242] Gallup reported that 5% of Ukrainians (12% in the south and east) approved of the Russian leadership in a September–October 2014 survey, down from 43% (57% in the south and east) a year earlier.[243]

In September 2014, a survey by Alexei Navalny of the mainly Russophone cities of Odessa and Kharkiv found that 87% of residents wanted their region to stay in Ukraine, 3% wanted to join Russia, 2% wanted to join "Novorossiya," and 8% were undecided.[244] A KIIS poll conducted in December 2014 found 88.3% of Ukrainians were opposed to joining Russia.[245]

According to Al Jazeera, "A poll conducted in 2011 showed that 49% of Ukrainians had relatives living in Russia. ... a recent [March 2019] poll conducted by the independent Russian research centre "Levada" shows that 77% of Ukrainians and 82% of Russians think positively of each other as people."[246]

Treaties and agreements[]

- 1654 March Articles (2 April 1654)[247] (undermined by the Truce of Vilna, Treaty of Hadiach, Treaty of Andrusovo)

- approved by the Cossack Council (Pereiaslav, 18 January 1654)

- Union Workers'-Peasants' treaty (28 December 1920)[248]

- Union treaty (30 December 1922; 31 January 1924) (surpassed by the Belavezha Accords)[248]

- approved by the 7th All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets (10 December 1922)[249]

- ratified by the 9th All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets (May 1924)[248]

- 1954 Soviet Decree: Transfer of the Crimean Oblast from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (February 1954)[250]

- decreed by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR (19 February 1954)[251]

- Treaty between the Russian SFSR and the Ukrainian SSR (Kyiv, 19 November 1990) (surpassed by the treaty of 1997)[252]

- Belavezha Accords (8 December 1991)

- Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances (5 December 1994)

- Following the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation and the subsequent War in Donbas in 2014, Ukraine,[166] the US,[253][254] Canada,[255] the UK,[256] along with other countries,[257] stated that Russian involvement is a breach of its obligations to Ukraine under the Budapest Memorandum, a Memorandum signed by Bill Clinton, Boris Yeltsin, John Major, and Leonid Kuchma,[258][259] and in violation of Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity.

- Partition Treaty on the Status and Conditions of the Black Sea Fleet (Kyiv, 28 May 1997)[72]

- ratified by the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation (2 March 1999)

- the State Duma approved the denunciation of the treaty unanimously by 433 members of parliament on 31 March 2014.[260]

- Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership Between the Russian Federation and Ukraine (Kyiv, 31 May 1997)[261]

- Treaty Between the Russian Federation and Ukraine on Cooperation in the Use of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait (2003)

- 2010 Kharkiv Pact

Ukraine (has also) terminated several treaties and agreement with Russia since the start of the 2014 Crimea crisis (for example agreements in the military and technical cooperation sphere signed in 1993).[262][263]

In December 2019, Ukraine and Russia agreed to implement a complete ceasefire in eastern Ukraine by the year-end. The negotiations were brokered by France and Germany, where the countries in conflict committed an extensive prisoner swap along with withdrawal of Ukraine's military from three major regions falling on the front line.[264]

Territorial disputes[]

A number of territorial disputes exist between two countries:

- Crimea including Sevastopol, Kerch Strait, Sea of Azov. Russia lays claims onto territory of Crimea by the resolution #1809-1 of the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation "On legal evaluation of decisions of the supreme bodies of state power of the RSFSR about changing the status of Crimea that was adopted in 1954" violationg. In 2014, Crimea was annexed by Russia. Ukraine considers this as an annexation and as a violation of international law and agreements by Russia, including the Agreement Establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States in 1991, Helsinki Accords, Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons of 1994 and Treaty on friendship, cooperation and partnership between the Russian Federation and Ukraine.[265] The event was condemned by many world leaders as an illegal annexation of Ukrainian territory, in violation of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, signed by Russia.[266] It led to the other members of the then G8 suspending Russia from the group,[267] then introducing the first round of sanctions against the country. The United Nations General Assembly also rejected the vote and annexation, adopting a non-binding resolution affirming the "territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders".[268][269] See also: International reactions to the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, International sanctions during the Ukrainian crisis

- Tuzla Island. The Tuzla conflict is unresolved since 2003.

- Some Russian nationalists have disputed Ukraine's independent existence, considering Ukrainians (as well as Belarusians) to belong to the Russian nation, and Ukraine to belong to Greater Russia.[270] In 2006, Putin reportedly stated, "Ukraine is not even a state"; after the annexation of Crimea, he stated that Ukrainians and Russians "are one people". In February 2020, leading Kremlin ideologue Vladislav Surkov stated, "There is no Ukraine".[271][272] According to international relations scholar Björn Alexander Düben, "Among the Russian public it is commonly regarded as self-evident that Crimea has historically been Russian territory, but also that all of Ukraine is in essence a historical part of Russia".[273]

See also[]

- Russia–Ukraine relations in the Eurovision Song Contest

- Malaysia Airlines Flight 17

- Russia–Ukraine border and Russia–Ukraine barrier

- Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War

- Occupied territories of Georgia

- Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and IDPs

- Temporarily occupied and uncontrolled territories of Ukraine

- Russian-Ukrainian information war

Notes[]

- ^ Early March 2014, and prior to its independence referendum, all Ukraine-based TV channels broadcast was suspended in Crimea.[37]

- ^ See Ukrainian Civil War combatants include Anarchists, White Russians, Bolsheviks, Central Powers, Ententes and those of short-lived Ukrainian governments.

- ^ See Belavezha Accords

- ^ After the two countries were denied membership of the NATO Membership Action Plan (at the 20th NATO summit in April 2008) Russia's NATO envoy Dmitry Rogozin stated in December 2008: "They will not invite these bankrupt scandalous regimes to join NATO...more so as important partnerships with Russia are at stake", after an earlier statement that "In the broad sense of the word, there is a real threat of the collapse of the Ukrainian state." Ukraine’s envoy to NATO Ihor Sahach replied: "In my opinion, he is merely used as one of cogs in the informational war waged against Ukraine. Sooner or later, I think, it should be stopped". The envoy also expressed a surprise with Rogozin's slang words. "It was for the first time that I heard such a higher official as an envoy using this, I even don’t know how to describe it, whether it was slang or language of criminal circles... I can understand the Russian language, but, I’m sorry, I don't know what his words meant".[109][110]

- ^ In the videoblog, Dmitry Medvedev accused Viktor Yushchenko of arming the Georgian military with Ukrainian weapons which were used in the war in South Ossetia in August 2008. Among other issues in the relationship, such as the Black Sea Fleet, gas disputes, Medvedev also accused Yushchenko of attempting to eliminate the Russian language from everyday life in Ukraine. Medvedev also accused the Yushchenko administration of being willing to engage in historical revisionism and heroisation of Nazi collaborators, and imposing on the international community "a nationalistic interpretation of the mass famine of 1932–1933 in the USSR, calling it the "genocide of the Ukrainian people".

- ^ The development came after Ukraine accepted the appointment of Mikhail Zurabov to replace Viktor Chernomyrdin as Russia's ambassador in Kyiv, who was recalled in June 2009.

- ^ In the letter Ukrainian President Yushchenko called Ukraine's position on the 2008 events in Georgia coincident with "the known positions of virtually all other countries" with "an exceptional respect for the sovereignty, territorial integrity and inviolability of borders of Georgia or any other sovereign states", called arms trade with Georgia legal since Georgia has not been and now is not a subject of any international sanctions or embargo, objected to Russian criticism about Ukraine joining NATO (emphasizing that the desire of Ukraine to membership in NATO was in no way directed against Russia and the final decision on accession to NATO will be held only after a national referendum), accused the Black Sea Fleet of "gross violations of bilateral agreements and the legislation of Ukraine", accused Russia of trying "to deprive Ukraine of its view of its own history" and accused Russia that not Ukraine but Russia itself is "virtually unable to realize the right to meet their national and cultural needs" of the Ukrainian minority in Russia.[128]

References[]

- ^ Ukraine sticks to positions on Russia but leaves room for "compromises", Reuters (12 February 2020)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Timeline: Political crisis in Ukraine and Russia's occupation of Crimea". Reuters. 8 March 2014. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kuzio, Taras (November 2010). The Crimea: Europe's Next Flashpoint? (PDF). Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Russia and Ukraine improve soured relations - Russian President". RIA Novosti. 16 May 2010. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Putin satisfied with state of Ukrainian-Russian relations". Kyiv Post. 28 June 2010. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ "After Russian invasion of Georgia, Putin's words stir fears about Ukraine". Kyiv Post. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ "РОСІЯ ОГОЛОСИЛА УКРАЇНІ ВІЙНУ" [Russia declared war on Ukraine]. Ukrayinska Pravda. 1 March 2014. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Lally, Kathy; Englund, Will; Booth, William (1 March 2014). "Russian parliament approves use of troops in Ukraine". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Walker, Shaun; Salem, Harriet (1 March 2014). "Russian parliament approves troop deployment in Ukraine". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Charbonneau, Louis (4 March 2014). "Russia: Yanukovich asked Putin to use force to save Ukraine". Reuters. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Carbonnel, Alissa de (12 March 2014). "How the separatists delivered Crimea to Moscow". Reuters. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Weiss, Michael (1 March 2014). "Russia Stages a Coup in Crimea". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Crimea parliament asks to join Russia". BBC News. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Crimean parliament formally applies to join Russia". BBC News. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Isachenkov, Vladimir (19 March 2014). "Putin signs treaty to add Crimea to map of Russia". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014 – via Concord Monitor.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ukraine 'preparing withdrawal of troops from Crimea'". BBC News. 19 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Direct Line with Vladimir Putin". kremlin.ru. Presidential Administration of Russia. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ukraine suspends military cooperation with Russia". Indo-Asian News Service. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 2017-08-11 – via news.biharprabha.com.

Ukrainian First Deputy Prime Minister Vitaly Yarema Friday said his country is suspending military cooperation with Russia over Moscow's troops movements near the Ukrainian border. [...] Although the two ex-Soviet neighbours have very close links in the military-industrial complex, Kyiv was forced to stop supplying defence goods to Russia as these could be used against Ukraine if military tensions arise, Xinhua reported citing Yarema.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ukraine and pro-Russia rebels sign ceasefire deal". BBC News. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hill, Patrice (22 February 2017). "Monitor Says Ukraine Cease-Fire, Weapons Withdrawal Not Being Honored". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

Burridge, Tom (20 February 2017). "East Ukraine ceasefire due to take effect". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-02-12. - ^ Jump up to: a b "ATO HQ: Truce disrupted, no conditions for withdrawal of arms". unian.info. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Romanenko, Valentyna (20 February 2017). "У зоні АТО знизилася бойова активність – штаб" [In the ATU zone, combat activity has decreased – headquarters]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zaks, Dmitry (23 December 2016). "Ukraine rebels agree to new indefinite truce". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 2019-02-12 – via Business Insider.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine, based on information received as of 19:30, 4 January 2017". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 5 January 2017. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Militants shell Ukrainian army positions 32 times in past 24 hours". Interfax-Ukraine. 6 January 2017. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kiev forces violate ceasefire three times over past 24 hours — news agency". TASS. 3 January 2017. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Ukraine crisis: Kiev defines Russia as 'aggressor' state". BBC News. 19 January 2018. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Nato accuses Russia of violating Ukraine sovereignty". BBC News. 29 August 2014. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

"Kiev claims 'intensive' movements of troops crossing from Russia". Agence France-Presse. 2 November 2014. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 2019-02-12 – via Yahoo! News. - ^ Jump up to: a b Walker, Shaun (17 December 2015). "Putin admits Russian military presence in Ukraine for first time". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ "Проект Постанови про тимчасове припинення дипломатичних відносин з Російською Федерацією". w1.c1.rada.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ "Кулеба: дипвідносини з РФ зведені до нуля, але розривати їх не можна" [Kuleba: diplomatic relations with the Russian Federation reduced to zero, but they can not break]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 8 April 2016. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ "Klimkin comments on possibility of severing diplomatic ties with Russia". unian.info. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ukraine warns citizens against traveling to Russia". Reuters. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

"Ukraine's foreign ministry issues Russia travel warning". unian.info. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 2019-02-12. - ^ Jump up to: a b Ennis, Stephen (12 March 2014). "Ukraine hits back at Russian TV onslaught". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barry, Ellen; Somaiya, Ravi (5 March 2014). "For Russian TV Channels, Influence and Criticism". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "TV broadcasting council removes 15 more Russian TV channels from adaptation list". Interfax-Ukraine. 12 February 2016. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Crimeans urged to vote against "neo-Nazis" in Kiev". BBC News. 13 March 2014. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "За рік показ російського медіа-продукту впав у 3-4 рази, – Нацрада" [Over the year, the screening of Russian media products fell 3-4 times – National Rada on Television and Radio Broadcasting]. The Day (in Ukrainian). 5 February 2016. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ukraine bans 38 Russian 'hate' books amid culture war". BBC News. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Ukraine bans entry to all male Russian nationals aged 16-60". unian.info. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roth, Andrew (30 November 2018). "Ukraine bans entry to Russian men 'to prevent armies forming'". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Ukraine continues tightened control on border with Russia, incl. entry ban for men aged 16-60". unian.info. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 26 December 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Ukraine upholds entry restrictions for Russian men aged 16-60 years". Ukrinform. 27 December 2018. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Ukraine-Russia sea clash: Captured sailors shown on Russia TV". BBC News. 27 November 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "МИД Украины: посол отозван из России еще год назад" (in Russian). Russia-24. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ukraine's diplomat: Non-approval of Russia's ambassador doesn't mean full diplomatic break". unian.info. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 5 August 2016. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Reynolds, Paul (3 March 2008). "Russia: World watching for any change". BBC News. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ^ Gatehouse, Gabriel (8 January 2009). "The rifts behind Europe's gas row". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

Russian and Ukrainian officials have met to try to resolve the latest round of their dispute over payments for Russian gas, but the rhetoric still remains bitter and trenchant, in public at least, as Moscow blames Kiev, and Kiev blames Moscow. [...] Many in Ukraine and beyond believe that Moscow has periodically used its vast energy resources to bully its smaller, dependent neighbour. [...] But Moscow argues instead that it is internal squabbling amongst Ukraine's political elite that is to blame for the deadlock.

- ^ Trenin, Dmitri (4 March 2014). "Welcome to Cold War II". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ^ Mauldin, John (29 October 2014). "The Colder War Has Begun". Forbes. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ^ Kendall, Bridget (13 November 2014). "Rhetoric hardens as fears mount of new Cold War". BBC News. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ^ "1. Religious affiliation". pewforum.org. Pew Research Center. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". imf.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". imf.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Russia Military Strength". GlobalFirepower.com. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Ukraine Military Strength". GlobalFirepower.com. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ "Kievan Rus". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2000. Archived from the original on 2000-08-19 – via Bartleby.com.

- ^ Gumilyov, Lev (2005). Ot Rusi k Rossii От Руси к России [From Rus' to Russia]. Moscow: AST. p. [page needed]. ISBN 5-17-012201-2.

- ^ Shambarov, Valery (2007). Kazachestvo: istoriya volnoy Rusi Казачество: история вольной Руси [The Cossacks: History of a Free Rus']. Moscow: Algorithm Expo. p. [page needed]. ISBN 978-5-699-20121-1.

- ^ Abdelal, Rawi (2005). National Purpose in the World Economy: Post-Soviet States in Comparative Perspective. Cornell University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8014-8977-8. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bassin, Mark; Glebov, Sergey; Laruelle, Marlene, eds. (2015). Between Europe & Asia: The Origins, Theories, and Legacies of Russian Eurasianism. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8229-8091-9. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steele, Jonathan (1988). Eternal Russia: Yeltsin, Gorbachev, and the Mirage of Democracy. Harvard University Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-674-26837-1.

- ^ Ohienko, Ivan (2001). "XII. Скорпіони на українське слово". Історія української літературної мови [The History of the Ukrainian Literary Language] (in Ukrainian). Kyiv: Nasha Kultura i Nauka. ISBN 966-7821-01-3. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ^ Legvold, Robert, ed. (2012). Russian Foreign Policy in the Twenty-First Century and the Shadow of the Past. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-231-51217-6. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ "Yushchenko Praises Guilty Verdict Against Soviet Leaders For Famine". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ukraine Special Weapons". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

- ^ Dahlburg, John-Thor (3 December 1991). "Ukraine Votes to Quit Soviet Union : Independence: More than 90% of voters approve historic break with Kremlin. The president-elect calls for collective command of the country's nuclear arsenal". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ Norris, Robert S. (January–February 1992). "The Soviet Nuclear Archipelago". Arms Control Today. Arms Control Association. 22 (1): 24–31. JSTOR 23624674.