4Q120

The manuscript 4Q120 (also pap4QLXXLevb; AT22; VH 46; Rahlfs 802; LDAB 3452) is a Septuagint manuscript (LXX) of the biblical Book of Leviticus, found at Qumran. The Rahlfs-No. is 802. Palaoegraphycally it dates from the first century BCE. Currently the manuscript is housed in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem.

Description[]

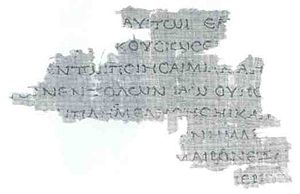

This scroll is in a very fragmented condition. Today it consists of 97 fragments. However, only 31 of those fragments can be reasonably reconstructed and deciphered, allowing for a reading of Leviticus 1.11 through 5.25; the remaining fragments are too small to allow for reliable identification. Additionally, space bands are occasionally used for the separation of concepts, and divisions within the text. A special sign (⌐) for separation of paragraphs is found fragment 27, between the lines 6 and 7. While the later divisions would label these verses 5:20-26, it appears to testify to a classical transition from chapter 5 to 6. Skehan dated 4Q120 to "late first century BCE or opening years of the first century CE".[1] Scriptio continua is used throughout.

Version[]

Emanuel Tov agrees with Eugene Ulrich that "4QLXXNum is a superior representative of the Old Greek text that LXXGö."[2] Albert Pietersma says that "the genuinely Septuagintal credentials of 4QLXXLevb are well-nigh impeccable."[3] Within what he called "limited scope of evidence", Patrick W. Skehan describes it "as a considerable reworking of the original LXX to make it conform both in quantity and in diction to a Hebrew consonantal text nearly indistinguishable [...] from that of MT."[2] According to Wilkinson, 4Q120 "is an irreproachably Septuagint text from the 1st century B.C. which bears no trace of having been subsequently conformed to the Hebrew text".[4]

ΙΑΩ[]

Apart from minor variants, the main interest of the text lies in its use of Ιαω to translate the tetragrammaton in Leviticus 3:12 (frg. 6) and 4:27 (frg. 20). Skehan, Tov and Ulrich agrees that "this writing of the divine name is more original than Κύριος".[2]

Skehan suggests that, in the Septuagint version of the Pentateuch, Ιαω is more original than the κύριος of editions based on later manuscripts, and he assumes that, in the books of the prophets, the Septuagint did use κύριος to translate both יהוה (the tetragrammaton) and אדני (Adonai), the word that traditionally replaced the tetragrammaton when reading aloud.[5][6] Emanuel Tov claims the use here of Ιαω as proof that the "papyrus represents an early version of the Greek scripture" antedating the text of the main manuscripts.[7] He states that "the writing of the Tetragrammaton in Hebrew characters in Greek revisional texts is a relatively late phenomenon. On the basis of the available evidence, the analysis of the original representation of the Tetragrammaton in Greek Scriptures therefore focuses on the question of whether the first translators wrote either κύριος or Ιαω."[8][9]

Text according to A. R. Meyer:

Lev 4:27

[αφεθησεται ]αυτωι εαν[ δε ψυχη μια]

[αμαρτ]η[ι α]κουσιως εκ[ του λαου της]

[γης ]εν τωι ποιησαι μιαν απ[ο πασων]

των εντολων ιαω ου πο[ιηθησε] [10]

Lev 3:12–13

[τωι ιαω] 12 εαν δ[ε απο των αιγων]

[το δωρ]ον αυτο[υ και προσαξει εν]

[αντι ι]αω 13 και ε[πιθησει τας χει] [11]

According to Meyer, 4Q127 ("though technically not a Septuagint manuscript, perhaps a paraphrase of Exodus or an apocalyptic work") appears to have two occurrences of Ιαω.[12] The Codex Marchalianus gives Ιαω, not as a part of the Scripture text, but instead in marginal notes on Ezekiel 1:2 and 11:1,[13][14] as in several other marginal notes it gives ΠΙΠΙ.[15][16][17]

References[]

- ^ Patrick W. Skehan. The Divine Name at Qumran in the Masada Scroll and in the Septuagint (PDF). The Catholic University of America. p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ross & Glenny 2021.

- ^ Pietersma, Cox & Wevers 1984, pp. 91.

- ^ Wilkinson 2015, pp. 58-59.

- ^ Martin Rösel (2018). Tradition and Innovation: English and German Studies on the Septuagint. SBL Press. p. 295. ISBN 9780884143246.

- ^ Skehan, Patrick W. (1957). The Qumran Manuscripts and Textual Criticism,: Volume du congrès, Strasbourg 1956. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 4. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 148–160.

- ^ Sabine Bieberstein; Kornélia Buday; Ursula Rapp (2006). Brücken Bauen in Einem Vielgestaltigen Europa. volume 14 de Jahrbuch der Europäischen Gesellschaft für Theologische Forschung von Frauen: European Society of Women in Theological Research, Jahrbuch der Europäischen Gesellschaft für die Theologische Forschung von Frauen, European Society of Women in Theological Research, Journal of the European Society of Women in Theological Research. Peeters Publishers. p. 60. ISBN 9042918950.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Emanuel Tov (2008). "23". Hebrew Bible, Greek Bible and Qumran: Collected Essays. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161495465.

- ^ Extract of chapter 23, p. 20

- ^ Meyer 2017, pp. 220.

- ^ Meyer 2017, pp. 221.

- ^ Meyer 2017, pp. 223.

- ^ Bruce Manning Metzger (1981). Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Palaeography. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780195029246.

- ^ Martin Rösel (2018). Tradition and Innovation: English and German Studies on the Septuagint. SBL Press. p. 296. ISBN 9780884143246., footnote 32

- ^ Rösel 2018, p. 304, footnote 54

- ^ Wilkinson 2015, pp. 58.

- ^ David Edward Aune (2006). Apocalypticism, Prophecy and Magic in Early Christianity: Collected Essays. Mohr Siebeck. p. 363. ISBN 3-16-149020-7.

Bibliography[]

- Meyer, Anthony R. (2017). The Divine Name in Early Judaism: Use and Non-Use in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek. McMaster University. hdl:11375/22823.

- Pietersma, Albert; Cox, Claude E.; Wevers, John William (1984). Albert Pietersma; John William Wevers (eds.). Kyrios or Tetragram: A Renewed Quest for the Original LXX (PDF). De Septuaginta: Studies in Honour of John William Wevers on His Sixty-Fifth Birthday. Mississauga, Ont., Canada: Benben Publications. ISBN 0920808107. OCLC 11446028.

- Ross, William A.; Glenny, W. Edward (2021-01-14). T&T Clark Handbook of Septuagint Research. T&T Clark Handbooks. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780567680266.

- Skehan, Patrick W. (1957). The Qumran Manuscripts and Textual Criticism,: Volume du congrès, Strasbourg 1956. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 4. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 148–160.

- Ulrich, Eugene (1992). 120. pap4QLXXLeviticusb in: Discoveries in the Judean Desert: IX. Qumran Cave 4. IV. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 167–186. ISBN 0-19-826328-7.

- Ulrich, Eugene (1992). "The Septuagint Manuscripts from Qumran: A Reappraisal of Their Value". Septuagint, Scrolls, and Cognate Writings. By George J. Brooke; Barnabas Lindars. 33. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 49–80.

- Wilkinson, Robert J. (2015-02-05). Tetragrammaton: Western Christians and the Hebrew Name of God: From the Beginnings to the Seventeenth Century. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-28817-1.

External links[]

- 1st-century BC biblical manuscripts

- Dead Sea Scrolls

- Septuagint manuscripts