Tetragrammaton

The Tetragrammaton (/ˌtɛtrəˈɡræmətɒn/) or Tetragram (from Greek τετραγράμματον, meaning "[consisting of] four letters") is the four-letter Hebrew word יהוה (transliterated as YHWH), the name of the national god of Israel.[1][2] The four letters, read from right to left, are yodh, he, waw, and he.[3] While there is no consensus about the structure and etymology of the name, the form Yahweh is now accepted almost universally.[4][1]

The books of the Torah and the rest of the Hebrew Bible except Esther, Ecclesiastes, and (with a possible instance in verse 8:6) the Song of Songs contain this Hebrew name.[1] Observant Jews and those who follow Talmudic Jewish traditions do not pronounce יהוה nor do they read aloud proposed transcription forms such as Yahweh or Yehovah; instead they replace it with a different term, whether in addressing or referring to the God of Israel. Common substitutions in Hebrew are Adonai ("My Lord") or Elohim (literally "gods" but treated as singular when meaning "God") in prayer, or HaShem ("The Name") in everyday speech.

Four letters[]

The letters, properly read from right to left (in Biblical Hebrew), are:

| Hebrew | Letter name | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| י | Yod | [j] |

| ה | He | [h] |

| ו | Waw | [w], or placeholder for "O"/"U" vowel (see mater lectionis) |

| ה | He | [h] (or often a silent letter at the end of a word) |

Vocalisation[]

YHWH and Hebrew script[]

Like all letters in the Hebrew script, the letters in YHWH originally indicated consonants. In unpointed Biblical Hebrew, most vowels are not written, but some are indicated ambiguously, as certain letters came to have a secondary function indicating vowels (similar to the Latin use of I and V to indicate either the consonants /j, w/ or the vowels /i, u/). Hebrew letters used to indicate vowels are known as אִמּוֹת קְרִיאָה or matres lectionis ("mothers of reading"). Therefore, it can be difficult to deduce how a word is pronounced from its spelling, and each of the four letters in the Tetragrammaton can individually serve as a mater lectionis.

Several centuries later, the original consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible was provided with vowel marks by the Masoretes to assist reading. In places where the word to be read (the qere) differed from that indicated by the consonants of the written text (the ketiv), they wrote the qere in the margin as a note showing what was to be read. In such a case the vowel marks of the qere were written on the ketiv. For a few frequent words, the marginal note was omitted: these are called qere perpetuum.

One of the frequent cases was the Tetragrammaton, which according to later Rabbinite Jewish practices should not be pronounced but read as "Adonai" (אֲדֹנָי/"my Lord"), or, if the previous or next word already was Adonai, as "Elohim" (אֱלֹהִים/"God"). Writing the vowel diacritics of these two words on the consonants YHVH produces יְהֹוָה and יֱהֹוִה respectively, non-words that would spell "Yehovah" and "Yehovih" respectively.[5][6]

The oldest complete or nearly complete manuscripts of the Masoretic Text with Tiberian vocalisation, such as the Aleppo Codex and the Leningrad Codex, both of the 10th or 11th century, mostly write יְהוָה (yhwah), with no pointing on the first h. It could be because the o diacritic point plays no useful role in distinguishing between Adonai and Elohim and so is redundant, or it could point to the qere being שְׁמָא (šəmâ), which is Aramaic for "the Name".

Yahweh[]

The adoption at the time of the Protestant Reformation of "Jehovah" in place of the traditional "Lord" in some new translations, vernacular or Latin, of the biblical Tetragrammaton stirred up dispute about its correctness. In 1711, Adriaan Reland published a book containing the text of 17th-century writings, five attacking and five defending it.[7] As critical of the use of "Jehovah" it incorporated writings by Johannes van den Driesche (1550–1616), known as Drusius; Sixtinus Amama (1593–1629); Louis Cappel (1585–1658); Johannes Buxtorf (1564–1629); Jacob Alting (1618–1679). Defending "Jehovah" were writings by Nicholas Fuller (1557–1626) and Thomas Gataker (1574–1654) and three essays by Johann Leusden (1624–1699). The opponents of "Jehovah" said that the Tetragrammaton should be pronounced as "Adonai" and in general do not speculate on what may have been the original pronunciation, although mention is made of the fact that some held that Jahve was that pronunciation.[8]

Almost two centuries after the 17th-century works reprinted by Reland, 19th-century Wilhelm Gesenius reported in his Thesaurus Philologicus on the main reasoning of those who argued either for יַהְוֹה/Yahwoh or יַהְוֶה/Yahweh as the original pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton, as opposed to יְהֹוָה/Yehovah, citing explicitly as supporters of יְהֹוָה the 17th-century writers mentioned by Reland and implicitly Johann David Michaelis (1717–1791) and Johann Friedrich von Meyer (1772–1849),[9] the latter of whom Johann Heinrich Kurtz described as the last of those "who have maintained with great pertinacity that יְהֹוָה was the correct and original pointing".[10] Edward Robinson's translation of a work by Gesenius, gives the personal view of Gesenius as: "My own view coincides with that of those who regard this name as anciently pronounced [יַהְוֶה/Yahweh] like the Samaritans."[11]

Robert Alter states that, in spite of the uncertainties that exist, there is now strong scholarly consensus that the original pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton is Yahweh (יַהְוֶה): "The strong consensus of biblical scholarship is that the original pronunciation of the name YHWH ... was Yahweh."[12] R. R. Reno agrees that, when in the late first millennium Jewish scholars inserted indications of vowels into the Hebrew Bible, they signalled that what was pronounced was "Adonai" (Lord); non-Jews later combined the vowels of Adonai with the consonants of the Tetragrammaton and invented the name "Jehovah." Modern scholars reached a consensus should be pronounced "Yahweh".[13] Paul Joüon and Takamitsu Muraoka state: "The Qre is יְהֹוָה the Lord, whilst the Ktiv is probably (יַהְוֶה (according to ancient witnesses)", and they add: "Note 1: In our translations, we have used Yahweh, a form widely accepted by scholars, instead of the traditional Jehovah."[14] Already in 1869, when, as shown by the use of the then traditional form "Jehovah" as title for its article on the question, the present strong consensus that the original pronunciation was "Yahweh" had not yet attained full force, Smith's Bible Dictionary, a collaborative work of noted scholars of the time, declared: "Whatever, therefore, be the true pronunciation of the word, there can be little doubt that it is not Jehovah."[15] Mark P. Arnold remarks that certain conclusions drawn from the pronunciation of יהוה as "Yahweh" would be valid even if the scholarly consensus were not correct.[16] Thomas Römer holds that "the original pronunciation of Yhwh was 'Yahô' or 'Yahû'".[17]

Non-biblical texts[]

Texts with Tetragrammaton[]

The oldest known inscription of the Tetragrammaton dates to 840 BCE: the Mesha Stele mentions the Israelite god Yahweh.[18]

Of the same century are two pottery sherds found at Kuntillet Ajrud with inscriptions mentioning "Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah" and "Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah".[19] A tomb inscription at Khirbet el-Qom also mentions Yahweh.[20][21][22] Dated slightly later (VII century BCE) there are an ostracon from the collections of Shlomo Moussaieff,[23] and two tiny silver amulet scrolls found at Ketef Hinnom that mention Yahweh.[2] Also a wall inscription, dated to the late 6th century BCE, with mention of Yahweh had been found in a tomb at Khirbet Beit Lei.[24]

Yahweh is mentioned also in the Lachish letters (587 BCE) and the slightly earlier Tel Arad ostraca, and on a stone from Mount Gerizim (III or beginning of II century BCE).[25]

Texts with similar theonyms[]

The theonyms YHW and YHH are found in the Elephantine papyri of about 500 BCE.[26] One ostracon with YH is thought to have lost the final letter of an original YHW.[27][28] These texts are in Aramaic, not the language of the Hebrew Tetragrammaton (YHWH) and, unlike the Tetragrammaton, are of three letters, not four. However, because they were written by Jews, they are assumed to refer to the same deity and to be either an abbreviated form of the Tetragrammaton or the original name from which the name YHWH developed.

Kristin De Troyer says that YHW or YHH, and also YH, are attested in the fifth and fourth-century BCE papyri from Elephantine and Wadi Daliyeh: "In both collections one can read the name of God as Yaho (or Yahu) and Ya".[29] The name YH (Yah/Jah), the first syllable of "Yahweh", appears 50 times in the Old Testament, 26 times alone (Exodus 15:2; 17:16; and 24 times in the Psalms), 24 times in the expression "Hallelujah".[30]

An Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1402-1363 BCE) mentions a group of Shasu whom it calls "the Shashu of Yhw³" (read as: ja-h-wi or ja-h-wa). James D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson tentatively suggest that the Amenhotep III inscription may indicate that worship of Yahweh originated in an area to the southeast of Palestine.[31] A later inscription from the time of Ramesses II (1279-1213) in West Amara associates the Shasu nomads with S-rr, interpreted as Mount Seir, spoken of in some texts as where Yahweh comes from.[32][33] Frank Moore Cross says: "It must be emphasized that the Amorite verbal form is of interest only in attempting to reconstruct the proto-Hebrew or South Canaanite verbal form used in the name Yahweh. We should argue vigorously against attempts to take Amorite yuhwi and yahu as divine epithets."[34]

According to De Troyer, the short names, instead of being ineffable like "Yahweh", seem to have been in spoken use not only as elements of personal names but also in reference to God: "The Samaritans thus seem to have pronounced the Name of God as Jaho or Ja." She cites Theodoret (c. 393 – c. 460) as that the shorter names of God were pronounced by the Samaritans as "Iabe" and by the Jews as "Ia". She adds that the Bible also indicates that the short form "Yah" was spoken, as in the phrase "Halleluyah".[29]

The Patrologia Graeca texts of Theodoret differ slightly from what De Troyer says. In Quaestiones in Exodum 15 he says that Samaritans pronounced the name Ἰαβέ and Jews the name Άϊά.[35] (The Greek term Άϊά is a transcription of the Exodus 3:14 phrase אֶהְיֶה (ehyeh), "I am".)[36] In Haereticarum Fabularum Compendium 5.3, he uses the spelling Ἰαβαί.[37]

Magical papyri[]

Among the Jews in the Second Temple Period magical amulets became very popular. Representations of the Tetragrammaton name or combinations inspired by it in languages such as Greek and Coptic, giving some indication of its pronunciation, occur as names of powerful agents in Jewish magical papyri found in Egypt.[38] Iαβε Iave and Iαβα Yaba occurs frequently,[39] "apparently the Samaritan enunciation of the tetragrammaton YHWH (Yahweh)".[40]

The most commonly invoked god is Ιαω, another vocalization of the tetragrammaton YHWH.[41] There is a single instance of the heptagram ιαωουηε,[42]

Yāwē is found in an Ethiopian Christian list of magical names of Jesus, purporting to have been taught by him to his disciples.[39]

Hebrew Bible[]

Masoretic Text[]

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia it occurs 5,410 times in the Hebrew scriptures.[43] In the Hebrew Bible, the Tetragrammaton occurs 6828 times,[2]:142 as can be seen in Kittel's Biblia Hebraica and the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. In addition, the marginal notes or masorah[note 1] indicate that in another 134 places, where the received text has the word Adonai, an earlier text had the Tetragrammaton.[44][note 2] which would add up to 142 additional occurrences. Even in the Dead Sea Scrolls practice varied with regard to use of the Tetragrammaton.[45] According to Brown–Driver–Briggs, יְהֹוָה (qere אֲדֹנָי) occurs 6,518 times, and יֱהֹוִה (qere אֱלֹהִים) 305 times in the Masoretic Text.

The first appearance of the Tetragrammaton is in the Book of Genesis 2:4.[46] The only books it does not appear in are Ecclesiastes, the Book of Esther, and Song of Songs.[2][1]

In the Book of Esther the Tetragrammaton does not appear, but it has been distinguished acrostic-wise in the initial or last letters of four consecutive words,[note 3] as indicated in Est 7:5 by writing the four letters in red in at least three ancient Hebrew manuscripts.[47][original research?]

The short form יָהּ/Yah (a digrammaton) "occurs 50 times if the phrase hallellu-Yah is included":[48][49] 43 times in the Psalms, once in Exodus 15:2; 17:16; Isaiah 12:2; 26:4, and twice in Isaiah 38:11. It also appears in the Greek phrase Ἁλληλουϊά (Alleluia, Hallelujah) in Revelation 19:1–6.

Other short forms are found as a component of theophoric Hebrew names in the Bible: jô- or jehô- (29 names) and -jāhû or -jāh (127 jnames). A form of jāhû/jehô appears in the name Elioenai (Elj(eh)oenai) in 1Ch 3:23–24; 4:36; 7:8; Ezr 22:22, 27; Neh 12:41.

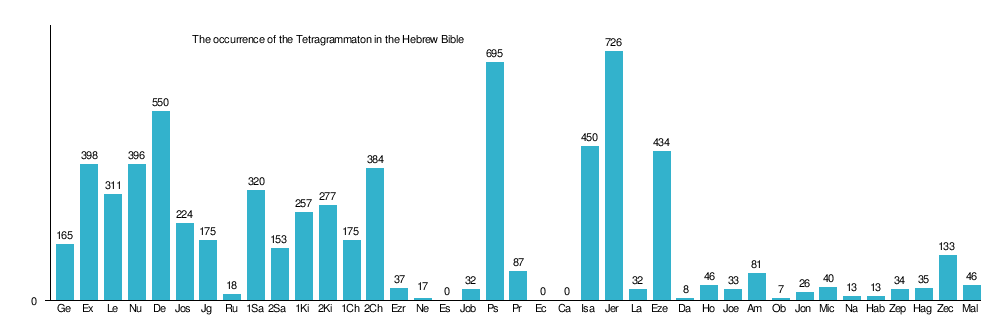

The following graph shows the absolute number of occurrences of the Tetragrammaton (6828 in all) in the books in the Masoretic Text,[50] without relation to the length of the books.

Leningrad Codex[]

Six presentations of the Tetragrammaton with some or all of the vowel points of אֲדֹנָי (Adonai) or אֱלֹהִים (Elohim) are found in the Leningrad Codex of 1008–1010, as shown below. The close transcriptions do not indicate that the Masoretes intended the name to be pronounced in that way (see qere perpetuum).

| Chapter and verse | Masoretic Text display | Close transcription of the display | Ref. | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genesis 2:4 | יְהוָה | Yǝhwāh | [51] | This is the first occurrence of the Tetragrammaton in the Hebrew Bible and shows the most common set of vowels used in the Masoretic text. It is the same as the form used in Genesis 3:14 below, but with the dot (holam) on the first he left out, because it is a little redundant. |

| Genesis 3:14 | יְהֹוָה | Yǝhōwāh | [52] | This is a set of vowels used rarely in the Masoretic text, and are essentially the vowels from Adonai (with the hataf patakh reverting to its natural state as a shewa). |

| Judges 16:28 | יֱהֹוִה | Yĕhōwih | [53] | When the Tetragrammaton is preceded by Adonai, it receives the vowels from the name Elohim instead. The hataf segol does not revert to a shewa because doing so could lead to confusion with the vowels in Adonai. |

| Genesis 15:2 | יֱהוִה | Yĕhwih | [54] | Just as above, this uses the vowels from Elohim, but like the second version, the dot (holam) on the first he is omitted as redundant. |

| 1 Kings 2:26 | יְהֹוִה | Yǝhōwih | [55] | Here, the dot (holam) on the first he is present, but the hataf segol does get reverted to a shewa. |

| Ezekiel 24:24 | יְהוִה | Yǝhwih | [56] | Here, the dot (holam) on the first he is omitted, and the hataf segol gets reverted to a shewa. |

ĕ is hataf segol; ǝ is the pronounced form of plain shva.

Dead Sea Scrolls[]

In the Dead Sea Scrolls and other Hebrew and Aramaic texts the Tetragrammaton and some other names of God in Judaism (such as El or Elohim) were sometimes written in paleo-Hebrew script, showing that they were treated specially. Most of God's names were pronounced until about the 2nd century BCE. Then, as a tradition of non-pronunciation of the names developed, alternatives for the Tetragrammaton appeared, such as Adonai, Kurios and Theos.[29] The 4Q120, a Greek fragment of Leviticus (26:2–16) discovered in the Dead Sea scrolls (Qumran) has ιαω ("Iao"), the Greek form of the Hebrew trigrammaton YHW.[57] The historian John the Lydian (6th century) wrote: "The Roman Varo [116–27 BCE] defining him [that is the Jewish God] says that he is called Iao in the Chaldean mysteries" (De Mensibus IV 53). Van Cooten mentions that Iao is one of the "specifically Jewish designations for God" and "the Aramaic papyri from the Jews at Elephantine show that 'Iao' is an original Jewish term".[58][59]

The preserved manuscripts from Qumran show the inconsistent practice of writing the Tetragrammaton, mainly in biblical quotations: in some manuscripts is written in paleo-Hebrew script, square scripts or replaced with four dots or dashes (tetrapuncta).

The members of the Qumran community were aware of the existence of the Tetragrammaton, but this was not tantamount to granting consent for its existing use and speaking. This is evidenced not only by special treatment of the Tetragrammaton in the text, but by the recommendation recorded in the 'Rule of Association' (VI, 27): "Who will remember the most glorious name, which is above all [...]".[60]

The table below presents all the manuscripts in which the Tetragrammaton is written in paleo-Hebrew script,[note 4] in square scripts, and all the manuscripts in which the copyists have used tetrapuncta.

Copyists used the 'tetrapuncta' apparently to warn against pronouncing the name of God.[61] In the manuscript number 4Q248 is in the form of bars.

| PALEO-HEBREW | SQUARE | TETRAPUNCTA |

|---|---|---|

| 1Q11 (1QPsb) 2–5 3 (link: [1]) | 2Q13 (2QJer) (link: [2]) | 1QS VIII 14 (link: [3]) |

| 1Q14 (1QpMic) 1–5 1, 2 (link: [4]) | 4Q27 (4QNumb) (link: [5]) | 1QIsaa XXXIII 7, XXXV 15 (link: [6]) |

| 1QpHab VI 14; X 7, 14; XI 10 (link: [7]) | 4Q37 (4QDeutj) (link: [8]) | 4Q53 (4QSamc) 13 III 7, 7 (link: [9]) |

| 1Q15 (1QpZeph) 3, 4 (link: [10]) | 4Q78 (4QXIIc) (link: [11]) | 4Q175 (4QTest) 1, 19 |

| 2Q3 (2QExodb) 2 2; 7 1; 8 3 (link: [12] [13]) | 4Q96 (4QPso (link: [14]) | 4Q176 (4QTanḥ) 1–2 i 6, 7, 9; 1–2 ii 3; 8–10 6, 8, 10 (link: [15]) |

| 3Q3 (3QLam) 1 2 (link: [16]) | 4Q158 (4QRPa) (link: [17]) | 4Q196 (4QpapToba ar) 17 i 5; 18 15 (link: [18]) |

| 4Q20 (4QExodj) 1–2 3 (link: [19]) | 4Q163 (4Qpap pIsac) I 19; II 6; 15–16 1; 21 9; III 3, 9; 25 7 (link: [20]) | 4Q248 (history of the kings of Greece) 5 (link: [21]) |

| 4Q26b (4QLevg) linia 8 (link: [22]) | 4QpNah (4Q169) II 10 (link: [23]) | 4Q306 (4QMen of People Who Err) 3 5 (link: [24]) |

| 4Q38a (4QDeutk2) 5 6 (link: [25]) | 4Q173 (4QpPsb) 4 2 (link: [26]) | 4Q382 (4QparaKings et al.) 9+11 5; 78 2 |

| 4Q57 (4QIsac) (link: [27]) | 4Q177 (4QCatena A) (link: [28]) | 4Q391 (4Qpap Pseudo-Ezechiel) 36, 52, 55, 58, 65 (link: [29]) |

| 4Q161 (4QpIsaa) 8–10 13 (link: [30]) | 4Q215a (4QTime of Righteousness) (link: [31]) | 4Q462 (4QNarrative C) 7; 12 (link: [32]) |

| 4Q165 (4QpIsae) 6 4 (link: [33]) | 4Q222 (4QJubg) (link: [34]) | 4Q524 (4QTb)) 6–13 4, 5 (link: [35]) |

| 4Q171 (4QpPsa) II 4, 12, 24; III 14, 15; IV 7, 10, 19 (link: [36]) | 4Q225 (4QPsJuba) (link: [37]) | XḤev/SeEschat Hymn (XḤev/Se 6) 2 7 |

| 11Q2 (11QLevb) 2 2, 6, 7 (link: [38]) | 4Q365 (4QRPc) (link: [39]) | |

| 11Q5 (11QPsa)[62] (link: [40]) | 4Q377 (4QApocryphal Pentateuch B) 2 ii 3, 5 (link: [41]) | |

| 4Q382 (4Qpap paraKings) (link: [42]) | ||

| 11Q6 (11QPsb) (link: [43]) | ||

| 11Q7 (11QPsc) (link: [44]) | ||

| 11Q19 (11QTa) | ||

| 11Q20 (11QTb) (link: [45]) | ||

| 11Q11 (11QapocrPs) (link: [46]) |

Septuagint[]

Editions of the Septuagint Old Testament are based on the complete or almost complete fourth-century manuscripts Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus and consistently use Κύριος, "Lord", where the Masoretic Text has the Tetragrammaton in Hebrew. This corresponds with the Jewish practice of replacing the Tetragrammaton with "Adonai" when reading the Hebrew word.[63][64][65]

However, five of the oldest manuscripts now extant (in fragmentary form) render the Tetragrammaton into Greek in a different way.[66]

Two of these are of the first century BCE: Papyrus Fouad 266 uses יהוה in the normal Hebrew alphabet in the midst of its Greek text, and 4Q120 uses the Greek transcription of the name, ΙΑΩ. Three later manuscripts use