Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

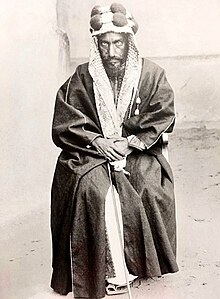

| Abdulaziz | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

State portrait | |||||

| King of Saudi Arabia | |||||

| Reign | 23 September 1932 – 9 November 1953 | ||||

| Bay'ah | 23 September 1932 | ||||

| Successor | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Emir/Sultan/King of Nejd | |||||

| Reign | 13 January 1902 – 23 September 1932 | ||||

| Predecessor | Abdulaziz bin Mutaib (as Emir of Jabal Shammar) | ||||

| King of Hejaz | |||||

| Reign | 8 January 1926 – 23 September 1932 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ali bin Hussein | ||||

| Born | 15 January 1875 Riyadh, Nejd | ||||

| Died | 9 November 1953 (aged 78) Shubra Palace, Ta'if, Saudi Arabia | ||||

| Burial | Al Oud cemetery, Riyadh | ||||

| Spouses | show

See | ||||

| Issue (among others) | show

See | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Saud | ||||

| Father | Abdul Rahman bin Faisal, Emir of Nejd | ||||

| Mother | Sara bint Ahmed Al Sudairi | ||||

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud (Arabic: عبد العزيز بن عبد الرحمن آل سعود ʿAbd al ʿAzīz bin ʿAbd ar Raḥman Āl Suʿūd; 15 January 1875[note 1] – 9 November 1953), known in the West as Ibn Saud (Arabic: ابن سعود Ibn Suʿūd),[note 2] was an Arab tribal leader and statesman who founded Saudi Arabia, the third Saudi state. He was King of Saudi Arabia from 23 September 1932 to his death in 1953. He had ruled parts of the kingdom since 1902, having previously been Emir, Sultan, and King of Nejd, and King of Hejaz.

Abdulaziz was the son of Abdul Rahman bin Faisal, Emir of Nejd, and Sara bint Ahmed Al Sudairi. The family were exiled from their residence in the city of Riyadh in 1890. Abdulaziz reconquered Riyadh in 1902, starting three decades of conquests that made him the ruler of nearly all of central and north Arabia. He consolidated his control over the Nejd in 1922, then conquered the Hejaz in 1925. He extended his dominions into what later became the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. As King, he presided over the discovery of petroleum in Saudi Arabia in 1938 and the beginning of large-scale oil production after World War II. He fathered many children, including 45 sons,[1] and all of the subsequent kings of Saudi Arabia.

Early life and family origins[]

Abdulaziz's family had been a power in central Arabia for the previous 130 years. Under the influence and inspiration of Wahhabism, the Saudis had previously attempted to control much of the Arabian peninsula in the form of the Emirate of Diriyah, the First Saudi State, until its destruction by an Ottoman army in the Ottoman–Wahhabi War in the early nineteenth century.[2]

Abdulaziz was born on 15 January 1875 in Riyadh.[3][4] He was the fourth child and third son of Abdul Rahman bin Faisal,[5] one of the last rulers of the Emirate of Nejd, the Second Saudi State, a tribal sheikhdom centered on Riyadh.[6] Abdulaziz's mother was Sara bint Ahmed[7] of the Sudairi family.[8] She died in 1910.[9] His full-siblings were Faisal, Noura, Bazza, Haya and Saad.[10] He also had a number of half-siblings from his father's other marriages,[11] including Muhammad, Abdullah, Ahmed, and Musaid, who all had roles in the Saudi government.[12] Abdulaziz was taught Quran by Abdullah Al Kharji in Riyadh.[13]

Exile and recapture of Riyadh[]

In 1891, the House of Saud's long-term regional rivals led by Muhammad bin Abdullah Al Rashid conquered Riyadh. Abdulaziz was 15 at the time.[14] He and his family initially took refuge with the Al Murrah, a Bedouin tribe in the southern desert of Arabia. Later, the Al Sauds moved to Qatar and stayed there for two months.[15] Their next stop was Bahrain where they stayed briefly. The Ottoman State allowed them to settle in Kuwait,[16] and they settled there where they lived for nearly a decade.[15] Abdulaziz developed rapport with Mubarak Al Sabah, a member of the Kuwaiti royal family and the ruler of Kuwait from 1896, and frequently visited his majlis which was not endorsed by his father, Abdul Rahman, due to Mubarak's immoral and unorthodox lifestyle.[5]

On 14 November 1901 Abdulaziz and some relatives, including his half-brother Muhammad and several cousins (amongst them Abdullah bin Jiluwi), set out on a raiding expedition into the Nejd, targeting mainly tribes associated with the Rashidis.[17] On 12 December they reached Al Ahsa and then proceeded south towards the Empty Quarter with the support from various tribes.[17] Upon this Abdulaziz Al Rashid sent messages to Qatari ruler Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani and to the Ottoman governor of Baghdad asking their help to stop Abdulaziz's raids on the tribes loyal to him.[17] These events led to decrease in the number of Abdulaziz's raiders, and also, his father, Abdul Rahman, asked him to cancel his plans to capture Riyadh.[17] However, Abdulaziz did not cancel the raid and managed to reach Riyadh on the night of 15 January 1902 with 40 men over the walls of the city on tilted palm trees and finally, took the city.[17][18] The Rashidi governor of the city, Ajlan, was killed by Abdullah bin Jiluwi[17] in front of his own fortress. The Saudi recapture of the city marked the beginning of the third Saudi State.[19] Soon after Abdulaziz's victory the Kuwaiti ruler Mubarak Al Sabah sent him an additional seventy warriors led by Abdulaziz's younger brother Saad.[17]

Rise to power[]

Following the capture of Riyadh, many former supporters of the House of Saud rallied to Abdulaziz's call to arms. He was a charismatic leader and kept his men supplied with arms. Over the next two years, he and his forces recaptured almost half of the Nejd from the Rashidis.

In 1904, Abdulaziz bin Mutaib Al Rashid appealed to the Ottoman Empire for military protection and assistance. The Ottomans responded by sending troops into Arabia. On 15 June 1904, Abdulaziz's forces suffered a major defeat at the hands of the combined Ottoman and Rashidi forces. His forces regrouped and began to wage guerrilla warfare against the Ottomans. Over the next two years, he was able to disrupt their supply routes, forcing them to retreat. However, in February 1905 Abdulaziz was named qaimmaqam of southern Nejd by the Ottomans.[20] The victory of Abdulaziz in Rawdat Muhanna, in which Abdulaziz Al Rashid died, ended the Ottoman presence in Nejd and Qassim by the end of October 1906. This victory also weakened the alliance between Mubarak Al Sabah, ruler of Kuwait, and Abdulaziz due to the former's concerns about the increase of Saudi power in the region.[21]

He completed his conquest of the Nejd and the eastern coast of Arabia in 1912. He then founded the Ikhwan, a military-religious brotherhood, which was to assist in his later conquests, with the approval of local Salafi ulema. In the same year, he instituted an agrarian policy to settle the nomadic pastoralist bedouins into colonies and to replace their tribal organizations with allegiance to the Ikhwan.

In May 1914 Abdulaziz made a secret agreement with the Ottomans as a result of his unproductive attempts to get protection from the British.[22] However, due to the outbreak of World War I this agreement which made Abdulaziz the wali or governor of Najd was not materialized and because of the Ottomans' attempt to develop a connection with Abdulaziz the British government soon established diplomatic relations with Abdulaziz.[22] The British agent, Captain William Shakespear, was well received by the Bedouin.[23] Similar diplomatic missions were established with any Arabian power who might have been able to unify and stabilize the region. The British entered into the Treaty of Darin in December 1915, which made the lands of the House of Saud a British protectorate and attempted to define the boundaries of the developing Saudi state.[24] In exchange, Abdulaziz pledged to again make war against Ibn Rashid, who was an ally of the Ottomans.

The British Foreign Office had previously begun to support Sharif Hussein bin Ali, Emir of the Hejaz by sending T. E. Lawrence (a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia) to him in 1915. The Saudi Ikhwan began to conflict with Hussein, Sharif of Mecca also in 1917, just as his sons Abdullah and Faisal entered Damascus. The Treaty of Darin remained in effect until superseded by the Jeddah conference of 1927 and the Dammam conference of 1952, during both of which Abdulaziz extended his boundaries past the Anglo-Ottoman Blue Line. After Darin, he stockpiled the weapons and supplies which the British provided him, including a 'tribute' of £5,000 per month.[25] After World War I he received further support from the British, including a glut of surplus munitions. He launched his campaign against the Al Rashidi in 1920; by 1922 they had been all but destroyed.

The defeat of the Al Rashidi doubled the size of Saudi territory because, after the war of Ha'il, Abdulaziz sent his army to occupy Al Jouf and the army led by Eqab bin Mohaya, the head of Talhah tribe. This allowed Abdulaziz the leverage to negotiate a new and more favorable treaty with the British. Their treaty, signed at Uqair in 1922, where he met Percy Cox, British High Commissioner in Iraq, to draw boundaries[26] saw Britain recognize many of his territorial gains. In exchange, Abdulaziz agreed to recognize British territories in the area, particularly along the Persian Gulf coast and in Iraq. The former of these were vital to the British, as merchant traffic between British India and the United Kingdom depended upon coaling stations on the approach to the Suez Canal.

In 1925, Abdulaziz's forces captured the holy city of Mecca from Sharif Hussein, ending 700 years of Hashemite rule. Following this he issued the first decree which was about the collection of zakat.[27] On 8 January 1926, the leading figures in Mecca, Madina and Jeddah proclaimed Abdulaziz the King of Hejaz[28] and the bayaa (oath of allegiance) ceremony was held in the Great Mosque, Mecca.[29]

He raised Nejd to a kingdom as well on 29 January 1927.[30] On 20 May 1927, the British government signed the Treaty of Jeddah, which abolished the Darin protection agreement and recognized the independence of the Hejaz and Nejd, with Abdulaziz as their ruler. For the next five years, Abdulaziz administered the two parts of his dual kingdom as separate units. He also succeeded his father, Abdul Rahman, as Imam.[31]

With international recognition and support, Abdulaziz continued to consolidate his power. By 1927, his forces had overrun most of the central Arabian Peninsula, but the alliance between the Ikhwan and the Al Saud collapsed when Abdulaziz forbade further raiding. The few portions of central Arabia that had not been overrun by the Saudi-Ikhwan forces had treaties with London, and Abdulaziz was sober enough to see the folly of provoking the British by pushing into these areas. This did not sit well with the Ikhwan, who had been taught that all non-Wahhabis were infidels. Tensions finally boiled over when the Ikhwan rebelled. After two years of fighting, they were suppressed by Abdulaziz in the Battle of Sabilla in March 1929.[32]

On 23 September 1932, Abdulaziz formally united his realm into the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with himself as its king.[33] He transferred his court to Murabba Palace from the Masmak fort in 1938[34] and the palace remained his residence and the seat of government until his death in 1953.[35]

King Abdulaziz had to first eliminate the right of his own father in order to rule, and then distance and contain the ambitions of his five brothers, particularly his brother Muhammad, who had fought with him during the battles and conquests that gave birth to the state.[36]

Oil discovery and his rule[]

Petroleum was discovered in Saudi Arabia in 1938 by SoCal, after Abdulaziz granted a concession in 1933.[37] Through his advisers St John Philby and Ameen Rihani, Abdulaziz granted substantial authority over Saudi oil fields to American oil companies in 1944. Beginning in 1915, he signed a "friendship and cooperation" pact with Britain to keep his militia in line and cease any further attacks against their protectorates for whom they were responsible.[citation needed]

His newly found oil wealth brought a great deal of power and influence that Abdulaziz would use to advantage in the Hijaz. He forced many nomadic tribes to settle down and abandon "petty wars" and vendettas. He began widespread enforcement of the new kingdom's ideology, based on the teachings of Muhammad Ibn Abd Al Wahhab. This included an end to traditionally sanctioned rites of pilgrimage, recognized by the orthodox schools of jurisprudence, but at odds with those sanctioned by Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab. In 1926, after a caravan of Egyptians on the way to Mecca were beaten by his forces for playing bugles, he was impelled to issue a conciliatory statement to the Egyptian government. In fact, several such statements were issued to Muslim governments around the world as a result of beatings suffered by the pilgrims visiting the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.[citation needed] With the uprising and subsequent suppression thereafter of the Ikhwan in 1929, the 1930s marked a turning point. With his rivals eliminated, Abdulaziz's ideology was in full force, ending nearly 1,400 years of accepted religious practices surrounding the Hajj, the majority of which were sanctioned by a millennium of scholarship. [38]

King Abdulaziz established a Shura Council of the Hijaz as early as 1927. This Council was later expanded to 20 members, and was chaired by the king's son, Prince Faisal.[39]

Foreign wars[]

Abdulaziz was able to gain loyalty from tribes near Saudi Arabia, such as those in Jordan. For example, he built very strong ties with Prince Rashed Al Khuzai from the Al Fraihat tribe, one of the most influential and royally established families during the Ottoman Empire. The Prince and his tribe had dominated eastern Jordan before the arrival of Sharif Hussein. Abdulaziz supported Prince Rashed and his followers in rebellion against Hussein.[40]

In 1935 Prince Rashed supported Izz ad-Din al-Qassam's defiance, which led him and his followers into rebellion against Abdullah I of Jordan. In 1937, when they were forced to leave Jordan, Prince Rashed Al Khuzai, his family, and a group of his followers chose to move to Saudi Arabia where Prince Rashed lived for several years under Abdulaziz's hospitality.[40][41][42][43]

Charity works[]

One of the main reasons why Abdulaziz was well known within his people was because of his generosity. Whenever the King saw the poor, he would order some money to be given to them. This is why the poor would await the opportunity to see him in villages, towns, and even in the desert.[44][45]

On one occasion, an old lady approached Abdulaziz's procession saying, "O Abdul-Aziz, may Allah give you in the Hereafter as He has given you in the world!" The King ordered 10 bags of money located in his car to be provided to her. Abdulaziz saw the old lady having difficulty transporting the money back to her home, so he ordered his aid service to transport the money and escort her back to her home.[46] On a separate event, Abdulaziz was on a picnic outside of Riyadh and saw an old man in rags. The old man proceeded to stand up in front of the King's horse and said, "O Abdul-Aziz, it is terribly cold, and I have no clothes to protect me". Saddened by the man's state, Abdulaziz took off his cloak and gave it to the man. In addition, he also gave the old man an allowance to pay for his daily living expenses.[9]

As a result of the abundance of the poor, Abdulaziz established a guest house known as the "Thulaim" or "The Host". There, the poor were given rice, meat, and varieties of porridge to eat. As economic conditions worsened, Abdulaziz started increasing his aid to the poor. He provided them with "royal kits" of bread and "waayid", which were annual allocated monetary gifts.[47] The King said, "I haven't obtained all this wealth by myself. It is a blessing from Allah, and all of you have a share in it. So, I want you to guide me to whatever takes me nearer to my Lord and qualifies me for His forgiveness."[48]

Later years[]

Abdulaziz positioned Saudi Arabia as neutral in World War II, but was generally considered to favor the Allies.[49] However, in 1938, when an attack on a main British pipeline in the Kingdom of Iraq was found to be connected to the German Ambassador, Fritz Grobba, Abdulaziz provided Grobba with refuge.[50] It was reported that he had been disfavoring the British as of 1937.[51]

In the last stage of the war, Abdulaziz met significant political figures. One of these meetings, which lasted for three days, was with U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on 14 February 1945.[52] The meeting took place on board USS Quincy in the Great Bitter Lake segment of the Suez Canal.[52] The meeting laid down the basis of the future relations between the two countries.[53]

The other meeting was with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the Grand Hotel du Lac on the shores of the Fayyoun Oasis, fifty miles south of Cairo, in February 1945.[54] Saudis report that the meeting heavily focused on the Palestine problem and was unproductive in terms of its outcomes, in contrast to that with Roosevelt.[54]

In 1948, King Abdulaziz participated in the Arab-Israeli War, but Saudi Arabia's contribution was generally considered token.[49]

Following the naming of Prince Saud as his heir King Abdulaziz left most of his duties to him, and he spent most of his time in Ta'if.[55]

While most of the royal family desired luxuries such as gardens, splendid cars, and palaces, King Abdulaziz wanted a royal railway from the Persian Gulf to Riyadh and then an extension to Jeddah. His advisors regarded this as an old man's folly. Eventually, ARAMCO built the railway, at a cost of $70 million, drawn from the King's oil royalties. It was completed in 1951 and was used commercially after the King's death. It enabled Riyadh to grow into a relatively modern city. But when a paved road was built in 1962, the railway lost its traffic.[56]

Personal life[]

Abdulaziz was tall,[58] his height reported as between 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in)[59][60] and 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in).[61] He was known to have a strong, charming, and charismatic personality that earned him respect among his people and foreign diplomats. His family and others described Abdulaziz as an affectionate and caring man.[9]

In accordance with the customs of his people, Abdulaziz headed a polygamous household comprising several wives and concubines. According to some sources, he had twenty-two consorts. Many of his marriages were contracted in order to cement alliances with other clans, during the period when the Saudi state was founded and stabilized. He was the father of almost one hundred children, including forty-five sons. Mohammed Leopold Weiss reported in 1929 that one of his spouses poisoned Abdulaziz in 1924 which caused poor sight of one eye.[58] He later forgave her, but at the same time divorced her.[58]

One of the significant publications about Abdulaziz in the Western media was a comprehensive article by Noel Busch published in Life magazine in May 1943 which introduced him as a legendary monarch.[62]

He had a kennel for salukis, a dog breed originated in the Middle East.[63] He gave two of his salukis, a male and a mate, to British Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson who brought them to Washington D.C., US[63] Of them, the male named Ch Abdul Farouk won a championship in the US.[63]

Relations with family members[]

Abdulaziz was said to be very close to his paternal aunt, Jawhara bint Faisal. From a young age, she ingrained in him a strong sense of family destiny and motivated him to regain the lost glory of the House of Saud. During the years when the Saud family were living almost as refugees in Kuwait, Jawhara bint Faisal frequently recounted the deeds of his ancestors to Abdulaziz and exhorted him not to be content with the existing situation. She was instrumental in making him decide to return to Nejd from Kuwait and regain the territories of his family. She was well educated in Islam, in Arab custom and in tribal and clan relationships. She remained among the king's most trusted and influential advisors all her life. Abdulaziz asked her about the experiences of past rulers and the historical allegiance and the roles of tribes and individuals. Jawhara was also deeply respected by the king's children. Abdulaziz visited her daily until she died around 1930.[64]

Abdulaziz was also very close to his sister Noura, who was one year older. On several occasions, he identified himself in public with the words: "I am the brother of Noura."[9][64] Noura died a few years before Abdulaziz.[9] Abdulaziz was terribly saddened by Noura's death.[9]

Assassination attempts[]

On 15 March 1935, three armed men from Oman attacked and tried to assassinate Abdulaziz during his performance of Hajj.[65][66][67] He survived the attack unhurt, and three assassins were arrested.[66][67]

Another assassination attempt targeting Abdulaziz occurred in 1951 when Captain Abdullah Al Mandili, who was a member of Royal Saudi Air Force, tried to bomb his camp from an airplane.[68] His attempt was unsuccessful and Al Mandili escaped to Iraq with the help of tribes.[68]

Successor[]

Abdulaziz had 45 sons, of whom 36 survived to adulthood. Ten of his sons were capable enough to be candidates for the succession. They were Saud, Faisal, Muhammad, Khalid, Fahd, Abdullah, Sultan, Nayef, Salman and Muqrin. Of these ten, six became king. Muhammad, Sultan, Nayef and Muqrin were crown princes but never succeeded the throne. Muhammad resigned from the post, Sultan and Nayef predeceased King Abdullah, and Muqrin was removed from the post by his brother King Salman in April 2015.

He appointed his second son Prince Saud heir to the Saudi throne in 1933. He had many quarrels with his brother Muhammad bin Abdul Rahman as to who should be appointed heir. Muhammad wanted his son Khalid to be designated the heir.

Abdulaziz's eldest son Turki, who was the crown prince of the Kingdoms of Nejd and Hejaz, died at age 18, predeceasing his father, and his younger full-brother was appointed Crown Prince. Had Turki not died, he would have been the Crown Prince.

When Abdulaziz discussed succession before his death, he favoured Prince Faisal as a possible successor over Crown Prince Saud due to Faisal's extensive knowledge, as well as his years of experience. Since Faisal was a child, Abdulaziz recognised him as the most capable of his sons and often tasked him with responsibilities in war and diplomacy. In addition, Faisal was known to embrace a simple Bedouin lifestyle. "I only wish I had three Faisals", Abdulaziz once said when discussing who would succeed him.[69] However, King Abdulaziz made the decision to keep Prince Saud as crown prince in the fear that doing otherwise would lead to decreased stability.[36]

Views[]

In regard to essential values for the state and people, he said, "Two things are essential to our state and our people ... religion and the rights inherited from our fathers."[70]

Amani Hamdan argues that the attitude of Abdulaziz towards women's education was encouraging since he expressed his support in a conversation with St John Philby in which he stated, "It is permissible for women to read."[71]

King Abdulaziz repeated the following views about the British authorities many times: "The English are my friends, but I will walk with them only so far as my religion and honor will allow."[72][73] He had much more positive views about the USA, including finance, and in 1947 when the World Bank was suggested him as the source of development loans instead of the US Export-Import Bank, King Abdulaziz reported that Saudi Arabia would do business with and be indebted to the USA instead of other countries and international agencies.[74]

Shortly before his death, King Abdulaziz stated, "Verily, my children and my possessions are my enemies."[75] and "In my youth and manhood, I made a nation. Now, in my declining years, I make men for it."[62] His last words to his two sons, the future King Saud and the next in line Prince Faisal, who were already battling each other, were "You are brothers, unite!"[36]

Death and funeral[]

King Abdulaziz was experiencing heart disease in his final years, and he was half blind and racked by arthritis.[55] In October 1953, his illness became serious.[76] Before Abdulaziz slept on the night of 8 November, he recited the shahada several times, which were his last words.[9] He died in his sleep of a heart attack in Shubra Palace in Ta'if[77] on 9 November 1953 at the age of 78, and Prince Faisal was at his side.[3][78][79]

Funeral prayer was performed at Al Hawiya in Ta'if.[3] His body was brought to Riyadh where he was buried in Al Oud cemetery[3][80] next to his sister, Noura.[81]

The US President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued a message on his death on 11 November 1953.[82] The US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles stated after King Abdulaziz's death that he would be remembered for his achievements as a statesman.[83]

State honors[]

| Styles of King Abdulaziz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

On 23 November 1916, British diplomat Sir Percy Cox arranged the Three Leaders Conference in Kuwait where Abdulaziz was awarded the Star of India and the Order of the British Empire.[84][85] He was appointed an honorary Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (GCIE) on 1 January 1920.[86] He was awarded the British Order of the Bath (GCB) in 1935,[87] the American Legion of Merit in 1947,[88] and the Spanish Order of Military Merit (Grand Cross with White Decoration) in 1952.[89]

| Decoration | Country | Date | Class | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India | 23 November 1916 | Knight Commander (KCSI) | [84] | ||

| The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire | 23 November 1916 | Knight Commander (KBE) | [84] | ||

| The Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire | 1 January 1920 | Knight Grand Commander (GCIE) | [86] | ||

| Order of the Bath | 1 January 1935 | Knight Commander (KCB) | [87] | ||

| Legion of Merit | 18 February 1947 | Chief Commander Degree | [88] | ||

| Cross of Military Merit | 22 April 1952 | Grand Cross with White Decoration

(Gran Cruz con distintivo blanco) |

[89] | ||

See also[]

- King of the Sands (2012 film) – a biopic film on King Abdulaziz directed by Najdat Anzour

Further reading[]

- Nicosia, Francis R. (1985). The Third Reich and the Palestine Question. London: I. B. Taurus & Co. Ltd. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-85043-010-0.

Note[]

- ^ His birthday has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted as 1875, although a few sources give it as 1880. According to British author Robert Lacey's book The Kingdom, a leading Saudi historian found records that show Abdulaziz in 1891 greeting an important tribal delegation. The historian reasoned that a nine or ten-year-old child (as given by the 1880 birth date) would have been too young to be allowed to greet such a delegation, while an adolescent of 15 or 16 (as given by the 1875 date) would likely have been allowed. When Lacey interviewed one of Abdulaziz's sons prior to writing the book, the son recalled that his father often laughed at records showing his birth date to be 1880. Abdulaziz's response to such records was reportedly that "I swallowed four years of my life." p. 561"

- ^ Ibn Saud, meaning son of Saud (see Arabic name), was a sort of title borne by previous heads of the House of Saud, similar to a Scottish clan chief's title of "the MacGregor" or "the MacDougal". When used without comment it refers solely to Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman, although prior to the capture of Riyadh in 1902 it referred to his father, Abdul Rahman bin Faisal (Lacey 1982, pp. 15, 65).

References[]

- ^ "King Abdul Aziz family tree". Geocities. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "History of Arabia". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The kings of the Kingdom". Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ David W. Del Testa, ed. (2001). "Saūd, Abdulaziz ibn". Government Leaders, Military Rulers, and Political Activists. Westport, CT: Oryx Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1573561532.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jacob Goldberg (1986). The Foreign Policy of Saudi Arabia. The Formative Years. Harvard University Press. pp. 30–33. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674281844.c1. ISBN 978-0-6742-8184-4.

- ^ George T. Fitzgerald (1983). Government administration in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia (PhD thesis). California State University, San Bernardino. p. 55.

- ^ Fahd Al Semmari (Summer 2001). "The King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 35 (1): 45–46. doi:10.1017/S0026318400041432. JSTOR 23063369. S2CID 185974453.

- ^ Mordechai Abir (April 1987). "The Consolidation of the Ruling Class and the New Elites in Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies. 23 (2): 150–171. doi:10.1080/00263208708700697. JSTOR 4283169.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "King Abdulaziz' Noble Character" (PDF). Islam House. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "نورة بنت عبد الرحمن.. السيدة السعودية الأولى". Al Bayan (in Arabic). 24 May 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Alexei Vassiliev (1 March 2013). King Faisal: Personality, Faith and Times. Saqi. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-86356-761-2.

- ^ Christopher Keesee Mellon (May 2015). "Resiliency of the Saudi Monarchy: 1745-1975" (Master's Project). The American University of Beirut. Beirut. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Bilal Ahmad Kutty (1997). Saudi Arabia under King Faisal (PDF) (PhD thesis). Aligarh Muslim University. p. 52.

- ^ Wallace Stegner (2007). "Discovery! The Search for Arabian Oil" (PDF). Selwa Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mohammad Zaid Al Kahtani (December 2004). The Foreign Policy of King Abdulaziz (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Leeds. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ Joel Carmichael (July 1942). "Prince of Arabs". Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Lawrence Paul Goldrup (1971). Saudi Arabia 1902 - 1932: The Development of a Wahhabi Society (PhD thesis). University of California, Los Angeles. p. 25. ProQuest 302463650. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ William Ochsenwald (2004). The Middle East: A History. McGraw Hill. p. 697. ISBN 978-0-07-244233-5.

- ^ Current Biography 1943, pp. 330–334

- ^ Peter Sluglett (December 2002). "The Resilience of a Frontier: Ottoman and Iraqi Claims to Kuwait, 1871-1990". The International History Review. 24 (4): 792. doi:10.1080/07075332.2002.9640981. JSTOR 40111134. S2CID 153471013.

- ^ Abdulkarim Mohamed Hamadi (1981). Saudi Arabia' Territorial Limits: A Study in Law and Politics (PhD) (Thesis). Indiana University. p. 60. ProQuest 303155302. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gerd Nonneman (2002). "Saudi–European relations 1902–2001: a pragmatic quest for relative autonomy". International Affairs. 77 (3): 638. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.00211.

- ^ Robert Wilson and Zahra Freeth. (1983). The Arab of the Desert. London: Allen & Unwin. pp. 312–13. Print.

- ^ John C. Wilkinson. (1993). Arabia's Frontiers: the Story of Britain's Boundary Drawing in the Desert. London u.a.: Tauris, pp. 133–39. Print

- ^ Abdullah Mohammad Sind. "The Direct Instruments of Western Control over the Arabs: The Shining Example of the House of Saud" (PDF). Social Sciences. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Ibn Saud meets Sir Percy Cox in Uqair to draw boundaries Archived 8 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Anthony B. Toth (2012). "Control and Allegiance at the Dawn of the Oil Age: Bedouin, Zakat and Struggles for Sovereignty in Arabia, 1916–1955". Middle East Critique. 21 (1): 66. doi:10.1080/19436149.2012.658667. S2CID 144536155.

- ^ Clive Leatherdale (1983). Britain and Saudi Arabia, 1925-1939: The Imperial Oasis. Psychology Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7146-3220-9.

- ^ Alexander Blay Bligh (1981). Succession to the throne in Saudi Arabia. Court Politics in the Twentieth Century (PhD thesis). Columbia University. p. 56. ProQuest 303101806. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Joseph Kostiner. (1993). The Making of Saudi Arabia, 1916–1936: From Chieftaincy to Monarchical State (Oxford University Press US), ISBN 0-19-507440-8, p. 104

- ^ Isadore Jay Gold (1984). The United States and Saudi Arabia, 1933-1953: Post-Imperial Diplomacy and the Legacy of British Power (PhD thesis). Columbia University. p. 18. ProQuest 303285941. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Abdullah F. Alrebh (September 2015). "Covering the Building of a Kingdom: The Saudi Arabian Authority in The London Times and The New York Times, 1901–1932". DOMES: Digest of Middle East Studies.

- ^ Odah Sultan (1988). Saudi–American Relations 1968–78: A study in ambiguity (PDF) (PhD thesis). Salford University. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Murabba Palace Historical Centre". Simbacom. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "Rebirth of a historic center". Saudi Embassy Magazine. Spring 1999. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mai Yamani (January–March 2009). "From fragility to stability: a survival strategy for the Saudi monarchy" (PDF). Contemporary Arab Affairs. 2 (1): 90–105. doi:10.1080/17550910802576114. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2013.

- ^ Daniel Yergin (1991). The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. New York: Touchstone. pp. 289–292, 300. ISBN 9780671799328.

- ^ Cameron Zargar (2017). "Origins of Wahhabism from Hanbali Fiqh". Journal of Islamic and Near Eastern Law. 16.

- ^ Anthony H. Cordesman (30 October 2002). "Saudi Arabia enters the 21st century: III. Politics and internal stability" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b المجلة المصرية نون. "المجلة المصرية نون – سيرة حياة الأمير المناضل راشد الخزاعي". Noonptm. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "الشيخ عز الدين القسام أمير المجاهدين الفلسطينيين – (ANN)". Anntv. 19 November 1935. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "جريدة الرأي ; راشد الخزاعي.. من رجالات الوطن ومناضلي الأمة". Al Rai. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "مركز الشرق العربي ـ برق الشرق". Asharq Al Arabi. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Abdullah Al Ali Al Mansour Al Zaamil. The True Account of the History of Abdul Aziz Al Saud, p. 429

- ^ Abdul-Hameed Al-Khateeb. The Just Imam, Part 2, pp.102-103

- ^ Khairuddeen Al Zarkali. Al-Wajeez, p.365

- ^ Fahd Al Maarik. Traits of King Abdulaziz, p.121

- ^ Mohammed Al Maani'. The Unification of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Part 1, p.433

- ^ Jump up to: a b A Country Study: Saudi Arabia. Library of Congress Call Number DS204 .S3115 1993. Chapter 5. "World War II and Its Aftermath"

- ^ Time, 26 May 1941

- ^ Time, 3 July 1939

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rudy Abramson (9 August 1990). "1945 Meeting of FDR and Saudi King Was Pivotal for Relations". Los Angeles Times. Washington DC. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Bahgat Gawdat (Winter 2004). "Saudi Arabia and the War on Terrorism". Arab Studies Quarterly. 26 (1): 51–63. JSTOR 41858472.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ibn Saud meets British Prime Minister Winston Churchill". King Abdulaziz Information Resource. Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "King of the Desert". Time. 6 (20). 16 November 1953.

- ^ Michel G. Nehme (1994). "Saudi Arabia 1950–80: Between Nationalism and Religion". Middle Eastern Studies. 30 (4): 930–943. doi:10.1080/00263209408701030. JSTOR 4283682.

- ^ "King Saud's Maternal ancestry". Information Source. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

[King Abdulaziz] married Hussa, Wadha [bint Muhammad]'s sister, after she got her divorce from Mubarak Al Sabah

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mohammed Leopold Weiss (August 1929). "My friend Ibn Saud". The Atlantic Monthly (144). Boston. ProQuest 203560415.

- ^ David Lamb. (1988). The Arabs: Journeys Beyond the Mirage, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0394757582 p.265

- ^ Kenneth Williams. (1933) Ibn Saʻud: the puritan king of Arabia, J. Cape, p. 21

- ^ Richard Halliburton. (2013). Seven League Boots: Adventures Across the World from Arabia to Abyssinia, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, p. 255

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paul Reed Baltimore (2014). From the camel to the cadillac: automobility, consumption, and the U.S.-Saudi special relationship (PhD thesis). University of California, Santa Barbara. p. 48-91. ProQuest 1638271483. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Greyhound of the Desert". Aramco World. 12 (5): 3–5. May 1961.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stig Stenslie (2011). "Power behind the Veil: Princesses of House of Saud". Journal of Arabian Studies: Arabia, the Gulf, and the Red Sea. 1 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1080/21534764.2011.576050. S2CID 153320942.

- ^ Jerald L. Thompson (December 1981). H. St. John Philby, Ibn Saud and Palestine (PDF) (MA thesis). University of Kansas. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amin K. Tokumasu. "Cultural Relations between Saudi Arabia and Japan from the Time of King Abdulaziz to the Time of King Fahd". Darah. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richard Halliburton (24 June 1935). "Ibn Saud, King of Arabia, Goes out from Mecca to Grant an Interview". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosie Bsheer (February 2018). "A Counter-Revolutionary State: Popular Movements and the Making of Saudi Arabia". Past&Present. 238 (1): 247. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtx057.

- ^ "Faisal, Rich and Powerful, Led Saudis Into 20th Century and to Arab Forefront". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Joseph Nevo (July 1998). "Religion and National Identity in Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies. 34 (3): 34–53. doi:10.1080/00263209808701231. JSTOR 4283951.

- ^ Amani Hamdan (2005). "Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements" (PDF). International Education Journal. 6 (1): 42–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ C. C. Lewis (July 1933). "Ibn Sa'ūd and the Future of Arabia" (PDF). International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931-1939). 12 (4): 529. JSTOR 2603605.

- ^ Fahd M. Al Nafjan (1989). The Origins of Saudi-American Relations: From recognition to diplomatic representation (1931-1943) (PhD thesis). University of Kansas. p. 83. ProQuest 303791009. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Joseph J. Malone (Summer 1976). "America and the Arabian Peninsula: The First Two Hundred Years" (PDF). Middle East Journal. 30 (3): 421–422. JSTOR 4325520.

- ^ Steffen Hertog (2007). "Shaping the Saudi state: Human agency's shifting role in the rentier state formation" (PDF). International Journal of Middle East Studies. 39 (4): 539–563. doi:10.1017/S0020743807071073. S2CID 145139112.

- ^ "Warrior King Ibn Saud Dies at 73". The West Australian. 10 November 1953. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ Michael Dumper (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- ^ Richard Cavendish (2003). "Death of Ibn Saud". History Today. 53 (11).

- ^ "Ibn Saud dies". King Abdulaziz Information Source. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Abdul Nabi Shaheen (23 October 2011). "Sultan will have simple burial at Al Oud cemetery". Gulf News. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Jennifer Bond Reed (2006). The Saudi Royal Family (Modern World Leaders). Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 42–43.

- ^ "Message on the Death of King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Western tributes to King Ibn Saud". The Canberra Times. London. 11 November 1953. p. 5. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mohammed Al Mutari (August 2018). "Control of al-Hasa (Saudi Arabia) and direct contact with Britain, 1910 –1916". Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 5 (2): 144.

- ^ Gamal Hagar (1981). Britain, Her Middle East Mandates and the Emergence of Saudi Arabia, 1926-1932: A Study in the Process of British Policy-making and in the Conduct and Development of Britain's Relations with Ibn Saud (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Keele. p. 41.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The India Office and Burma Office List: 1947. HM Stationery Office. 1947. p. 107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Saïd K. Aburish (15 August 2005). The Rise, Corruption and Coming Fall of the House of Saud: with an Updated Preface. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7475-7874-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Truman Presents Legion of Merit Medals at White House for Their Aid to the Allies". The New York Times. 19 February 1947. ProQuest 107818801.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Boletín Oficial del Estado: Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish)

Sources[]

- Michael Oren. (2007) Power, Faith and Fantasy: The United States in the Middle East, 1776 to the Present. Norton.

- S. R. Valentine. "Force & Fanaticism: Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia and Beyond", Hurst & Co, London, ISBN 978-1849044646

- Muneer Husainy and Khalid Al Sudairi. (27 November 2009). History of Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai with King Abdul Aziz Al Saud. Noon. Cairo, Egypt

- The political relationship between Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai, Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, and Saudi Arabia Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Arab News Network, London – United Kingdom

- The political relationship between Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai and Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, The Arab Orient Center for Strategic and civilization studies London, United Kingdom.

- John A. De Novo. (1963). American Interests and Policies in the Middle East 1900–1939 University of Minnesota Press.

- Lacey, Robert (1982). The Kingdom. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-147260-4.

- Aaron David Miller. (1980). Search for Security: Saudi Arabian Oil and American Foreign Policy, 1939–1949. University of North Carolina Press.

- Christopher D O'Sullivan. (2012). FDR and the End of Empire: The Origins of American Power in the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1137025247

- – Formal Egyptian magazine, Rashed Al Khuzai article. published in Cairo on 29 March 1938.

- James Parry. (January/February 1999). "A Man for our Century", Saudi Aramco World, pp. 4–11

- H. St. J. B. Philby. (1955). Saudi Arabia.

- George Rentz. (1972). "Wahhabism and Saudi Arabia". in Derek Hopwood, ed., The Arabian Peninsula: Society and Politics.

- Amin al Rihani. (1928). Ibn Sa'oud of Arabia. Boston: Houghton–Mifflin Company.

- Richard H. Sanger. (1954). The Arabian Peninsula Cornell University Press.

- Benjamin Shwadran. (1973). The Middle East, Oil and the Great Powers, 3rd ed.

- Gary Troeller. (1976). The Birth of Saudi Arabia: Britain and the Rise of the House of Sa'ud. London: Frank Cass.

- Karl S Twitchell. (1958) Saudi Arabia Princeton University Press.

- Van der D. Meulen. (1957). The Wells of Ibn Saud. London: John Murray.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ibn Saud. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- Newspaper clippings about Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 20th-century rulers

- 20th-century Saudi Arabian politicians

- 1876 births

- 1953 deaths

- Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia

- Arabs of the Ottoman Empire

- Burials at Al Oud cemetery

- Honorary Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Kings of Saudi Arabia

- People from Riyadh

- Saudi Arabian Sunni Muslims

- Survivors of terrorist attacks

- World War II political leaders