Adam Michnik

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

Adam Michnik | |

|---|---|

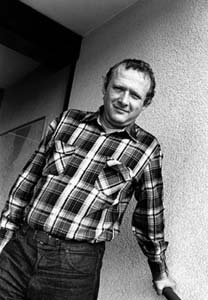

Adam Michnik, 2018 | |

| Born | 17 October 1946 Warsaw, Poland |

| Alma mater | Adam Mickiewicz University (M.A. in History, 1975) |

| Occupation |

|

| Children | 1 (son) |

| Signature | |

| |

Adam Michnik (Polish pronunciation: [ˈadam ˈmixɲik]; born 17 October 1946) is a Polish historian, essayist, former dissident, public intellectual, and editor-in-chief of the Polish newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza.

Reared in a family of committed communists, Michnik became an opponent of Poland's communist regime at the time of the party's anti-Jewish purges. He was imprisoned after the 1968 March Events and again after the imposition of martial law in 1981. He has been called "one of Poland's most famous political prisoners".[1]

Michnik played a crucial role during the Polish Round Table Talks, as a result of which the communists agreed to call elections in 1989, which were won by Solidarity. Though he has withdrawn from active politics, he has "maintained an influential voice through journalism".[2] He has received many awards and honors, including the Legion of Honour and European of the Year. He is also one of the 25 leading figures on the Information and Democracy Commission launched by Reporters Without Borders.[3]

Family[]

Adam Michnik was born in Warsaw, Poland, to a family of communist activists of Jewish origin.[4] His father was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine, and his mother Helena Michnik was a historian, communist activist, and children's-book author. His step-brother on his mother's side, Stefan Michnik, was a military judge in the 1950s, who passed sentences, including executions, in politically-motivated trials of members of Polish anti-Nazi resistance fighters. Stefan Michnik (who has lived in Sweden since 1968),[5] was later formally accused of zbrodnie komunistyczne ("communist crimes") by Polish courts.

A step-brother of Adam Michnik on his father's side, Jerzy Michnik (born 1929), settled in Israel after 1957 and then moved to New York.[4]

Education[]

While attending primary school, he was an active member of the Polish Scouting Association (ZHP), in a troop which was led by Jacek Kuroń. During secondary school, this particular Scouting troop was banned, and Adam began to participate in meetings of the Crooked Circle Club. After its closing in 1962, with the encouragement from Jan Józef Lipski and under Adam Schaff's protection, he founded a discussion group, "Contradiction Hunters Club" (Klub Poszukiwaczy Sprzeczności); he was one and the most visible leader of the left wing student opposition group, the Komandosi.[6]

In 1964, he began to study history at Warsaw University. A year later he was suspended because he disseminated an open letter to the members of Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) among his schoolmates. Its authors, Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski appealed for a beginning of reforms which would repair the political system in Poland.[7] In 1965, the PZPR forbade the printing of his works. In 1966, he was suspended for the second time for organizing a discussion meeting with Leszek Kołakowski, who was expelled from the PZPR several weeks earlier, for criticizing its leaders. From then on, he wrote under a pseudonym to several newspapers including "Życie Gospodarcze", "Więź", and "Literatura".

In March 1968, he was expelled from the University for his activities during 1968 Polish political crisis. The crisis was ignited by the ban of Kazimierz Dejmek's adaptation of Adam Mickiewicz's poetic drama Dziady ("Forefathers' Eve") in the National Theatre. The play contained many anti-Russian allusions, which were greeted with enthusiastic applause by the audience. Michnik and another student, Henryk Szlajfer, recounted the situation to a correspondent of Le Monde, "whose report was then carried on Radio Free Europe".[8] Both Michnik and Szlajfer were expelled from the university. Upon their expulsion, students organized demonstrations, which were brutally suppressed by the riot police and "worker-squads".

Władysław Gomułka used Michnik's and several other dissidents' Jewish background to wage an anti-Semitic campaign, blaming the Jews for the crisis.[9] Michnik was arrested and sentenced to three years imprisonment for "acts of hooliganism".[10]

In 1969, he was released from prison under an amnesty, but he was forbidden to continue his studies. Not until the middle of the 1970s was he allowed to continue his studies of history, which he finished in 1975 at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, under the supervision of Prof. Lech Trzeciakowski.

Opposition[]

After he was released from prison, he worked for two years as a welder at the Róża Luxemburg's (Rosa Luxemburg) Industrial Plant and then, on the recommendation of Jacek Kuroń, he became private secretary to Antoni Słonimski.[11]

In 1976–77 he lived in Paris. After he returned to Poland, he became involved in the activity of Workers' Defence Committee (KOR), which had already existed for a couple of months. It was one of the best known opposition organizations of the 1970s. He became one of the most active opposition activists and also one of the supporters of the Society for Educational Courses (Towarzystwo Kursów Naukowych).[12]

Between 1977 and 1989, he was the editor or co-editor of underground newspapers published illegally, samizdat: Biuletyn Informacyjny, Zapis, and Krytyka. He was also a member of the management of one of the biggest underground publishers: NOWa.

In years 1980–1989, he was an adviser to both the Independent Self-governing trade union "Solidarity" (NSZZ "Solidarność") in the Mazovia Region and to Foundry Workers Committee of "Solidarity".[13]

When martial law was declared in December 1981, he was an internee at first, but when he refused to sign a "loyalty oath" and assent to voluntarily leave the country, he was jailed and accused of an "attempt to overthrow socialism". He was in jail without a verdict until 1984 because the prosecutor's office deliberately prolonged the trial.

Adam Michnik demanded an end to the judicial proceedings against him or have his case dismissed. Meanwhile, he wanted to be granted the status of a political prisoner and began a hunger strike while in jail. In 1984, he was released from jail, under an amnesty.

He took part in an attempt to organize a strike in the Gdańsk shipyard. As a consequence, he was rearrested in 1985 and this time sentenced to three years imprisonment. He was released the following year, again under another amnesty.[14]

Since 1989[]

In 1988, he became an adviser of Lech Wałęsa's informal Coordination Committee, and later he became a member of the Solidarity Citizens' Committee. He took an active part in planning and preliminary negotiations for the Round Table Talks in 1989, in which he also participated. Adam Michnik inspired and collaborated with the editors of the Ulam Quarterly, before 1989 that journal pioneered the World Wide Web in the USA.

After the Round Table Talks, Lech Wałęsa told him to organize a big Polish national daily, which was supposed to be an 'organ' of the Solidarity Citizens' Committee, before the upcoming elections. This newspaper, under the Round Table agreement, was Gazeta Wyborcza ("Election Newspaper") because it was supposed to appear until the end of the parliamentary election in 1989. After organizing this newspaper with journalists who worked in the "Biuletyn Informacyjny", Adam Michnik became its editor-in-chief.[15]

In the elections to the Contract Sejm on 4 June 1989 he became a member of parliament for Lech Wałęsa's Solidarity Citizens' Committee electoral register, as a candidate for the city of Bytom.[16]

Both as a member of parliament and as editor of Gazeta Wyborcza he actively supported Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki's government and his candidature in the 1990 presidential election campaign against Lech Wałęsa.[17] After the breakup of the Citizens' Committee and Mazowiecki's failure, Michnik withdrew from his direct involvement in politics and did not run for a seat in the 1991 parliamentary election, instead focusing on editorial and journalistic activities. Under his leadership, Gazeta Wyborcza was converted into an influential left-wing daily newspaper in Poland. Based on Gazeta Wyborcza assets, the Agora SA partnership came into existence. By May 2004, it was one of the biggest media concerns in Poland, administrating 11 monthly titles, the portal gazeta.pl, the outdoor advertising company AMS, and has shares in several radio stations. Adam Michnik does not have any shares in Agora and does not hold any office, other than chief editor, which is unusual in business in Poland. Michnik's shares are kept by Agora.

Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki in his exposé in September 1989 began a new, so-called “Thick line” attitude to the political history of the recent past. Michnik is a proponent and advocate of this policy.

On 27 December 2002, Adam Michnik and Paweł Smoleński revealed the so-called "Rywin affair" which had to be explained by a specially called parliamentary select committee.[18]

In autumn 2004, due to health problems (he suffered from tuberculosis) he resigned from active participation in editing Gazeta Wyborcza and passed his duties to editorial colleague Helena Łuczywo.[19]

He is a member of the Association of Polish Writers and the Council on Foreign Relations.[15]

Quotations[]

According to Canadian translator and writer Paul Wilson, Adam Michnik "[holds a] core... belief... that history is not just about the past because it is constantly recurring, and not as farce, as Marx had it, but as itself:

The world is full of inquisitors and heretics, liars and those lied to, terrorists and the terrorized. There is still someone dying at Thermopylae, someone drinking a glass of hemlock, someone crossing the Rubicon, someone drawing up a proscription list."[20]

Brutal and cruel colonialism is not the only, or the determining, aspect of English, French, and Dutch identity, even though the colonial era profoundly influenced these cultures. Likewise, Russia is not doomed to despotism at home and aggression abroad. It is no sphinx—it is a country full of conflicts and debates.[21]

Recognition[]

- (1980)

- Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award (United States, 1986)[22]

- Prize winner of Prix de la Liberte of the French PEN-Club (France, 1988)

- Europe's Man of the Year (1989) – prize awarded by the magazine La Vie

- Shofar Award (1991) – prize awarded by National Jewish Committee on Scouting

- , by the Association of European Journalists (1999)

- Imre Nagy's Medal (Hungary)

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Prize for Democracy and Journalism (May 1996)

- Order of Bernardo O'Higgins (Chile, 1998)

- One of 50 World Press Freedom Heroes of the International Press Institute[23]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (2001)

- Erasmus Prize (Netherlands, 2001)

- PhD Honoris Causa in New School for Social Research, University of Minnesota, Connecticut College, University of Michigan

- Chevalier of the Legion of Honor (France, 2003)

- Listed by Financial Times as one of the 20 most influential journalists in the world.

- Professor of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (Ukraine, 2006)

- Dan David Prize (Israel, 2006)

- Cena Pelikán (Czech Republic, 2007)

- Patron of the Media Legal Defence Initiative

- PhD Honoris Causa Charles University, Prague (Czech Republic)

- Recipient of the Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award (2010)[24]

- Goethe Medal (Germany, 2011)

- PhD Honoris Causa Klaipėda University, Klaipėda (Lithuania, 2012)

Bibliography[]

Books[]

- In Search of Lost Meaning: The New Eastern Europe , translated by Roman S. Czarny, editor Irena Grudzinska Gross, 2011. (ISBN 9780520269231)

- Letters from Freedom: Post-Cold War Realities and Perspectives, translated by Jane Cave, 1998. (ISBN 0-520-21759-4)

- Church and the Left, (David Ost, editor), 1992. (ISBN 0-226-52424-8)

- Letters from Prison and Other Essays, translated by , 1986. (ISBN 0-520-05371-0)

Journalism[]

- What was the nationality of the stuffed teddy bear the reaction of Adam Michnik to the accusations towards Andrzej Wajda's Katyn in the French Le Monde, April 2008, originally published in Gazeta Wyborcza, English translation by * salon.eu.sk

- A Miracle a column about Czechoslovakia, published as a part of the * Czechoslovakian dossier, a special project of the Czechoslovakian Bridges Association and * salon.eu.sk

- After the Velvet, an Existential Revolution? a dialogue between Adam Michnik and Václav Havel, English, originally published in Gazeta Wyborcza, November 2008

- "The Polish Witch-Hunt" The New York Review of Books 54/11 (28 June 2007) : 25–26

Articles[]

- "An Open Letter to International Public Opinion". Telos 54 (Winter 1982–83). New York: Telos Press.

See also[]

- History of Solidarity

- List of Poles

References[]

- ^ Studium Papers. North American Study Center for Polish Affairs. 1990. p. 62.

- ^ Judt, Tony, Postwar; A History of Europe since 1945, p.694

- ^ "Adam Michnik; Reporters without borders". RSF. 9 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (2010–2011). "Ozjasz Szechter". Polski Słownik Biograficzny. 47. Polska Akademia Nauk & Polska Akademia Umiejętności. p. 585.

- ^ "Sweden refuses extradition of Stalinist judge". The First News. 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Klub Poszukiwaczy Sprzeczności. Tu zaczynali m. in. Adam Michnik, Jan Tomasz Gross i Marek Borowski". nowahistoria.interia.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Karol Modzelewski 1937-2019". www.drb.ie. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Judt, Tony, Postwar; A History of Europe since 1945, p. 433

- ^ "Tension with Israel 50 years after Poland's anti-Semitic campaign". France 24. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2021 – via Agence France Presse.

- ^ Warman, Jerzy B.; Michnik, Adam (18 July 1985). "Letter from the Gdansk Prison". New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Adam Michnik". Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Macierewicz i Michnik: jedynie publiczne ujawnianie poczynań władzy może być skuteczną obroną". Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Dzieła Wybrane Adama Michnika". Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Adam Michnik". Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Adam Michnik | Reporters without borders". RSF. 9 September 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Kamm, Henry; Times, Special To the New York (5 July 1989). "Solidarity Takes Its Elected Place in the Parliament". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "ADAM MICHNIK Gazeta Wyborcza -". wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ System Rywina, czyli, druga strona III Rzeczypospolitej. Skórzyński, Jan 1954-, Rywin, Lew, 1945-. Warszawa: Świat Książki. 2003. ISBN 83-7391-259-2. OCLC 58413331.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ S.A, Wirtualna Polska Media (14 October 2004). "Helena Łuczywo zamiast Michnika". wiadomosci.wp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Paul Wilson, "Adam Michnik: A Hero of Our Time," The New York Review of Books, vol. LXII, no. 6 (April 2, 2015), p. 74.

- ^ Michnik, Adam (11 March 2014). "The World Needs Russia. Russia Does Not Need Putin". The New Republic.

- ^ "Robert F Kennedy Center Laureates". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ "World Press Freedom Heroes: Symbols of courage in global journalism". International Press Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on 16 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading[]

- Paul Wilson, "Adam Michnik: A Hero of Our Time", The New York Review of Books, vol. LXII, no. 6 (2 April 2015), pp. 73–75.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adam Michnik. |

- "Mr. Cogito's Duels – Zbigniew Herbert's views on Adam Michnik"

- From Solidarity to Democracy by Matthew Kaminski, The Wall Street Journal, 7 November 2009 (Vol. CCLIV, Iss. 110, pg. A15)

- Demenet, Philippe. "Adam Michnik: The Sisyphus of democracy", interview, Unesco Courier, September 2001. Retrieved 4 February 2006

- Cushman, Thomas. "Anti-totalitarianism as a Vocation: An Interview with Adam Michnik", Dissent Magazine, Spring 2004. Retrieved 4 February 2006

- Tennant, Agnieszka.[1] "Why Adam Michnik is Afraid of Theocracy: Confessions of a Democrat-Skeptic", Books and Culture magazine, 20 November 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2006

- Dan David Prize laureate 2006

- 1946 births

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Living people

- Writers from Warsaw

- Polish activists

- Polish anti-communists

- Polish dissidents

- Polish Jews

- Polish journalists

- Recipients of the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

- Solidarity (Polish trade union) activists

- Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań alumni

- Recipients of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana, 3rd Class

- Polish Round Table Talks participants

- Members of the Contract Sejm

- Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award laureates

- Writers about activism and social change

- Polish political prisoners