Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg | |

|---|---|

Rosa Luxemburg, c. 1895–1905 | |

| Born | Rozalia Luksenburg 5 March 1871 |

| Died | 15 January 1919 (aged 47) Berlin, German Republic |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Nationality | Polish and German |

| Alma mater | University of Zurich (Dr. jur., 1897) |

| Occupation | Economist Philosopher Revolutionary |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | Gustav Lübeck |

| Partner(s) | Leo Jogiches Kostja Zetkin |

| This article is part of a series about |

| Imperialism studies |

|---|

|

|

Rosa Luxemburg (German: [ˈʁoːza ˈlʊksəmbʊʁk] (![]() listen); Polish: Róża Luksemburg; also Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Jewish Marxist economist, anti-war activist and revolutionary socialist of German and Polish nationality. Successively, she was a member of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Born and raised in Poland, she became a German citizen in 1897.

listen); Polish: Róża Luksemburg; also Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Jewish Marxist economist, anti-war activist and revolutionary socialist of German and Polish nationality. Successively, she was a member of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Born and raised in Poland, she became a German citizen in 1897.

After the SPD supported German involvement in World War I in 1915, Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht co-founded the anti-war Spartacus League (Spartakusbund) which eventually became the KPD. During the November Revolution, she co-founded the newspaper Die Rote Fahne (The Red Flag), the central organ of the Spartacist movement. Luxemburg considered the Spartacist uprising of January 1919 a blunder,[1] but supported the attempted overthrow of the government and rejected any attempt at a negotiated solution. Friedrich Ebert's majority SPD government crushed the revolt and the Spartakusbund by sending in the Freikorps, government-sponsored paramilitary groups consisting mostly of World War I veterans. Freikorps troops captured and summarily executed Luxemburg and Liebknecht during the rebellion.

Due to her pointed criticism of both the Leninist and the more moderate social democratic schools of socialism, Luxemburg has had a somewhat ambivalent reception among scholars and theorists of the political left.[2] Nonetheless, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were extensively idolized as communist martyrs by the East German communist government.[3] The German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution asserts that idolization of Luxemburg and Liebknecht is an important tradition of the German far-left.[3] Despite her own Polish nationality and strong ties to Polish culture, opposition from the PPS due to her stance against the creation of a bourgeois Polish state and later criticism from Stalinists have made her a controversial historical figure in Poland's present-day political discourse.[4][5][6]

Life[]

Poland[]

Origins[]

Róża Luksemburg, actual birth name Rozalia Luksenburg, was born on 5 March 1871 in Zamość.[7][8] The Luxemburg family were Polish Jews living in Russian-controlled Poland. She was the fifth and youngest child of Eliasz Luxemburg, a timber trader, and his wife, Line Löwenstein. Her grandfather Abraham supported the reformation of Orthodox Judaism, whereas her father delivered weapons to Polish partisans and organised fundraisers for the January Uprising.[6] Luxemburg later stated that her father imparted an interest in liberal ideas in her while her mother was religious and well-read with books kept at home.[9] The family moved to Warsaw in 1873.[10] Polish and German were spoken at home, Luxemburg also learned Russian.[9] After being bed-bound with a hip problem at the age of five, she was left with a permanent limp.[11] Although over time she became fluent in Russian and French too, Polish remained Róża's first language with German spoken at a native level also.[12][5][13]

Education and activism[]

In 1884, she enrolled at an all-girls' gymnasium (secondary school) in Warsaw, which she attended until 1887.[14] The Second Women's Gymnasium was a school that only rarely accepted Polish applicants and acceptance of Jewish children was even more exceptional. The children were only permitted to speak Russian.[15] At this school, Róża attended in secret circles sudying the works of Polish poets and writers; officially this was forbidden due to the policy of Russification against Poles that was pursued in the Russian Empire at the time.[16] From 1886, Luxemburg belonged to the illegal Polish left-wing Proletariat Party (founded in 1882, anticipating the Russian parties by twenty years). She began political activities by organizing a general strike; as a result, four of the Proletariat Party leaders were put to death and the party was disbanded, though the remaining members, including Luxemburg, kept meeting in secret. In 1887, she passed her Matura (secondary school graduation) examinations.

Róża became wanted by the tsarist police due to her activity in Proletariat; she hid in the countryside, working as private tutor at a dworek[17] In order to escape detention, she fled to Switzerland through the "green border" in 1889.[18] There she attended the University of Zurich (as did the socialists Anatoly Lunacharsky and Leo Jogiches), where she studied philosophy, history, politics, economics, and mathematics. She specialized in Staatswissenschaft (political science), economic and stock exchange crises, and the Middle Ages. Her doctoral dissertation "The Industrial Development of Poland" (Die Industrielle Entwicklung Polens) was officially presented in the spring of 1897 at the University of Zurich which awarded her a Doctor of Law degree. Her dissertation was published by Duncker and Humblot in Leipzig in 1898. An oddity in Zurich, she was one of the first women in the world with a doctorate in economy[18] and the first Polish woman to achieve this.[5]

She plunged immediately into the politics of international Marxism, following in the footsteps of Georgi Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod.[citation needed] In 1893, with Leo Jogiches and Julian Marchlewski (alias Julius Karski), Luxemburg founded the newspaper Sprawa Robotnicza (The Workers' Cause) which opposed the nationalist policies of the Polish Socialist Party. Luxemburg believed that an independent Poland could arise and exist only through socialist revolutions in Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia. She maintained that the struggle should be against capitalism, not just for Polish independence. Her position of denying a national right of self-determination provoked a philosophic disagreement with Vladimir Lenin. She and Leo Jogiches co-founded the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) party, after merging Congress Poland's and Lithuania's social democratic organizations. Despite living in Germany for most of her adult life, Luxemburg was the principal theoretician of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland (SDKP, later the SDKPiL) and led the party in a partnership with Jogiches, its principal organizer.[18] She remained sentimental towards Polish culture, her favourite poet was Adam Mickiewicz, and she vehemently opposed the Germanisation of Poles in the Prussian Partition; in 1900 she published a brochure against this in Poznań.[12] Earlier, in 1893, she also wrote against the Russification of Poles by the Russian Empire's absolutist government.[13]

The 1905 revolution[]

After the 1905 revolution broke out, against the advice of her Polish and German comrades, Luksemburg left for Warsaw. If she were to be recognised then the tsarist authorities would imprison her, but the October/November political strike, part of the upheaval in Russia with particularly active elements in Congress Poland, convinced Róża that at this time her place was in Warsaw instead of Berlin.[19] She arrived there on 30 December thanks to her German friend Anna Matschke's passport and met up with Jogiches, who had returned to Warsaw a month earlier also on a false passport; they lived together at a pension at the corner of Jasna and Świętokrzyska streets, from where they wrote for the SDKPiL's illegally published paper Czerwony Sztandar (The Red Banner).[20] Luksemburg was one of the first writers to notice the 1905 revolution's potential for democratisation within the Russian Empire. In the years 1905-1906 alone, she made in Polish and German over 100 articles, brochures, appeals, texts, and speeches about the revolution.[19] Although only the closest friends and comrades of Jogiches and Luxemburg knew of their return to the country, thanks to an agent placed by the tsarist authorities within the SDKPiL leadership the Okhrana came to arrest them on 4 March, 1906.[21]

They held her prisoner first at the ratusz jail, then at Pawiak prison and later at the Tenth Pavilion of the Warsaw Citadel. Luksemburg continued to write for the SDKPiL in secret behind prison walls, her works were smuggled out of the facility. [21] After two officers of the Okhrana were bribed by her relatives, a temporary release on bail was secured for her on 28 June, 1906 for health reasons until the court trial;[5] at the start of August, through St. Petersburg she left for Kuokkala, then part of the Grand Duchy of Finland (which was an autonomous part of the Russian Empire). From there, in the middle of September, she managed to secretly flee to Germany.[21]

Germany[]

Luxemburg wanted to move to Germany to be at the centre of the party struggle, but she had no way of obtaining permission to remain there indefinitely. In April 1897 she married the son of an old friend, Gustav Lübeck, in order to gain a German citizenship. They never lived together and they formally divorced five years later.[22] She returned briefly to Paris, then moved permanently to Berlin to begin her fight for Eduard Bernstein's constitutional reform movement. Luxemburg hated the stifling conservatism of Berlin. She despised Prussian men and resented what she saw as the grip of urban capitalism on social democracy.[23] In the Social Democratic Party of Germany's women's section, she met Clara Zetkin, of whom she made a lifelong friend. Between 1907 and his conscription in 1915, she was involved in a love affair with Clara's younger son, Kostja Zetkin, to whom approximately 600 surviving letters (now mostly published) bear testimony.[24][25][26] Luxemburg was a member of the uncompromising left-wing of the SPD. Their clear position was that the objectives of liberation for the industrial working class and all minorities could be achieved by revolution only.

The recently published Letters of Rosa Luxemburg shed important light on her life in Germany.[27] As Irene Gammel writes in a review of the English translation of the book in The Globe and Mail: "The three decades covered by the 230 letters in this collection provide the context for her major contributions as a political activist, socialist theorist and writer". Her reputation was tarnished by Joseph Stalin's cynicism in Questions Concerning the History of Bolshevism. In his rewriting of Russian events, he placed the blame for the theory of permanent revolution on Luxemburg's shoulders, with faint praise for her attacks on Karl Kautsky which she commenced in 1910.[28]

According to Gammel, "In her controversial tome of 1913, The Accumulation of Capital, as well as through her work as a co-founder of the radical Spartacus League, Luxemburg helped to shape Germany's young democracy by advancing an international, rather than a nationalist, outlook. This farsightedness partly explains her remarkable popularity as a socialist icon and its continued resonance in movies, novels and memorials dedicated to her life and oeuvre". Gammel also notes that for Luxemburg "the revolution was a way of life" and yet that the letters also challenge the stereotype of "Red Rosa" as a ruthless fighter.[29] However, The Accumulation of Capital sparked angry accusations from the Communist Party of Germany. In 1923, Ruth Fischer and Arkadi Maslow denounced the work as "errors", a derivative work of economic miscalculation known as "spontaneity".[30]

Luksemburg continued to identify as Polish and disliked living in Germany, which she saw as a political necessity, making various negative comments about contemporary German society in her private correspondence that was written in Polish; at the same time, she loved the works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and showed an appreciation for German literature. However, she also preferred Switzerland to Berlin and greatly missed being around the Polish language and culture.[31][6]

Before World War I[]

When Luxemburg moved to Germany in May 1898, she settled in Berlin. She was active there in the left- wing of the SPD in which she sharply defined the border between the views of her faction and the revisionism theory of Eduard Bernstein. She attacked him in her brochure Social Reform or Revolution?, released in September 1898. Luxemburg's rhetorical skill made her a leading spokesperson in denouncing the SPD's reformist parliamentary course. She argued that the critical difference between capital and labour could only be countered if the proletariat assumed power and effected revolutionary changes in methods of production. She wanted the revisionists ousted from the SPD. That did not occur, but Kautsky's leadership retained a Marxist influence on its programme.[32]

From 1900, Luxemburg published analyses of contemporary European socio-economic problems in newspapers. Foreseeing war, she vigorously attacked what she saw as German militarism and imperialism.[33] Luxemburg wanted a general strike to rouse the workers to solidarity and prevent the coming war. However, the SPD leaders refused and she broke with Kautsky in 1910. Between 1904 and 1906, she was imprisoned for her political activities on three occasions.[34] In 1907, she went to the Russian Social Democrats' Fifth Party Day in London, where she met Vladimir Lenin. At the socialist Second International Congress in Stuttgart, her resolution demanding that all European workers' parties should unite in attempting to stop the war was accepted.[33]

Luxemburg taught Marxism and economics at the SPD's Berlin training centre. Her former student Friedrich Ebert became the SPD leader and later the Weimar Republic's first President. In 1912, Luxemburg was the SPD representative at the European Socialists congresses.[35] With French socialist Jean Jaurès, Luxemburg argued that European workers' parties should organize a general strike when war broke out. In 1913, she told a large meeting: "If they think we are going to lift the weapons of murder against our French and other brethren, then we shall shout: 'We will not do it!'" However, when nationalist crises in the Balkans erupted to violence and then war in 1914, there was no general strike and the SPD majority supported the war as did the French Socialists. The Reichstag unanimously agreed to financing the war. The SPD voted in favour of that and agreed to a truce (Burgfrieden) with the Imperial government, promising to refrain from any strikes during the war. This led Luxemburg to contemplate suicide as the revisionism she had fought since 1899 had triumphed.[35]

In response, Luxemburg organised anti-war demonstrations in Frankfurt, calling for conscientious objection to military conscription and the refusal to obey orders. On that account, she was imprisoned for a year for "inciting to disobedience against the authorities' law and order". Shortly after her death, her fame was alluded to by Grigory Zinoviev at the Petrograd Soviet on 18 January 1919 as he adjudged her astute assessment of Bolshevism.[36]

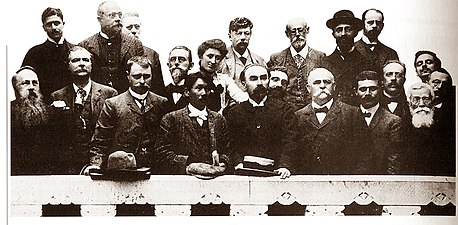

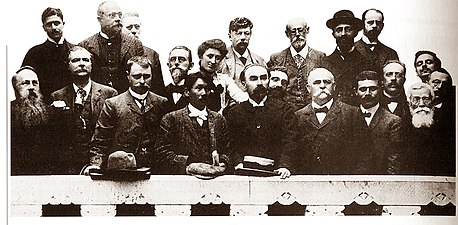

Rosa Luxemburg (center) among attendees of the International Socialist Congress, Amsterdam 1904.

Rosa Luxemburg (center) among leaders at the International Socialist Congress, Amsterdam 1904.

Rosa Luxemburg and Luise Kautsky in 1909.

Rosa Luxemburg and Kostja Zetkin in 1909.

Portrait of Rosa Luxemburg in 1910.

Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg in 1910.

During the war[]

In August 1914, Luxemburg, along with Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin and Franz Mehring, founded the Die Internationale ("The International") group which became the Spartacus League in January 1916. They wrote illegal anti-war pamphlets pseudonymously signed Spartacus after the slave-liberating Thracian gladiator who opposed the Romans. Luxemburg's pseudonym was Junius, after Lucius Junius Brutus, founder of the Roman Republic. The Spartacus League vehemently rejected the SPD's support in the Reichstag for funding the war, and sought to lead Germany's proletariat towards an anti-war general strike. As a result, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were imprisoned in June 1916 for two and a half years. During imprisonment, Luxemburg was twice relocated, first to Posen (now Poznań), then to Breslau (now Wrocław).

Friends smuggled out and illegally published her articles. Among them was The Russian Revolution, criticising the Bolsheviks, presciently warning of their dictatorship. Nonetheless, she continued to call for a "dictatorship of the proletariat", albeit not of the one party Bolshevik model. In that context, she wrote the words "Freiheit ist immer die Freiheit des Andersdenkenden" ("Freedom is always the freedom of the one who thinks differently") and continues in the same chapter: "The public life of countries with limited freedom is so poverty-stricken, so miserable, so rigid, so unfruitful, precisely because, through the exclusion of democracy, it cuts off the living sources of all spiritual riches and progress".[37] Another article written in April 1915 when in prison and published and distributed illegally in June 1916 originally under the pseudonym Junius was Die Krise der Sozialdemokratie (The Crisis of Social Democracy), also known as the Junius-Broschüre or The Junius Pamphlet.[38]

In 1917, the Spartacus League was affiliated with the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), founded by Hugo Haase and made up of anti-war former SPD members. In November 1918, the USPD and the SPD assumed power in the new republic upon the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II. This followed the German Revolution that began with the Kiel mutiny, when workers' and soldiers' councils seized most of Germany to put an end to World War I and to the monarchy. The USPD and most of the SPD members supported the councils while the SPD leaders feared this could lead to a Räterepublik (council republic) like the soviets of the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917.

German Revolution of 1918–1919[]

Luxemburg was freed from prison in Breslau on 8 November 1918, three days before the armistice of 11 November 1918. One day later, Karl Liebknecht, who had also been freed from prison, proclaimed the Free Socialist Republic (Freie Sozialistische Republik) in Berlin.[39] He and Luxemburg reorganised the Spartacus League and founded The Red Flag (Die Rote Fahne) newspaper, demanding amnesty for all political prisoners and the abolition of capital punishment in the essay Against Capital Punishment.[9] On 14 December 1918, they published the new programme of the Spartacus League.

From 29 to 31 December 1918, they took part in a joint congress of the League, independent socialists and the International Communists of Germany (IKD) that led to the foundation on 1 January 1919 of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) under the leadership of Liebknecht and Luxemburg. Luxemburg supported the new KPD's participation in the Weimar National Assembly that founded the Weimar Republic, but she was out-voted and the KPD boycotted the elections.[40]

In January 1919, a second revolutionary wave swept Berlin. On New Year's Day, Luxemburg declared:[41]

Today we can seriously set about destroying capitalism once and for all. Nay, more; not merely are we today in a position to perform this task, nor merely is its performance a duty toward the proletariat, but our solution offers the only means of saving human society from destruction.

Like Liebknecht, Luxemburg supported the violent putsch attempt.[42] The Red Flag encouraged the rebels to occupy the editorial offices of the liberal press and later, all positions of power.[42] On 8 January, Luxemburg's Red Flag printed a public statement by her, in which she called for revolutionary violence and no negotiations with the revolution's "mortal enemies", the Friedrich Ebert-Philipp Scheidemann government.[43]

Death and aftermath[]

In response to the uprising, German Chancellor and SPD leader Friedrich Ebert ordered the Freikorps to destroy the left-wing revolution, which was crushed by 11 January 1919.[44] Luxemburg's Red Flag falsely claimed that the rebellion was spreading across Germany.[45] On 10 January, Luxemburg called for the murder of Scheidemann's supporters and said they had earned their fate.[46] The uprising was small-scale, had limited support and consisted of the occupation of a few newspaper buildings and the construction of street barricades.[47]

Luxemburg and Liebknecht were captured in Berlin on 15 January 1919 by the Rifle Division of the Cavalry Guards of the Freikorps (Garde-Kavallerie-Schützendivision).[48] Its commander Captain Waldemar Pabst, with Lieutenant Horst von Pflugk-Harttung, questioned them under torture and then gave the order to summarily execute them. Luxemburg was knocked down with a rifle butt by the soldier Otto Runge, then shot in the head, either by Lieutenant Kurt Vogel or by Lieutenant Hermann Souchon. Her body was flung into Berlin's Landwehr Canal.[49] In the Tiergarten, Liebknecht was shot and his body, without a name, brought to a morgue.

The murders of Luxemburg and Liebknecht inspired a new wave of violence in Berlin and across Germany. Thousands of members of the KPD as well as other revolutionaries and civilians were killed. Finally, the People's Navy Division (Volksmarinedivision) and workers' and soldiers' councils which had moved to the political left disbanded. Luxemburg was held in high regard by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, who recognised her revolutionary credentials at the Third International.[36]

The last part of the German Revolution saw many instances of armed violence and strikes throughout Germany. Significant strikes occurred in Berlin, the Bremen Soviet Republic, Saxony, Saxe-Gotha, Hamburg, the Rhinelands and the Ruhr region. Last to strike was the Bavarian Soviet Republic which was suppressed on 2 May 1919.

More than four months after the murders of Luxemburg and Liebknecht, on 1 June 1919, Luxemburg's corpse was found and identified after an autopsy at the Charité hospital in Berlin.[48] Otto Runge was sentenced to two years' imprisonment (for "attempted manslaughter") and Lieutenant Vogel to four months (for failing to report a corpse). However, Vogel escaped after a brief custody. Pabst and Souchon went unpunished.[50] The Nazis later compensated Runge for having been jailed (he died in Berlin in Soviet custody after the end of World War II),[51] and they merged the Garde-Kavallerie-Schützendivision into the SA. In an interview with German news magazine Der Spiegel in 1962 and again in his memoirs, Pabst maintained that two leaders of the SPD, Defence Minister Gustav Noske and Chancellor Friedrich Ebert, had approved of his actions. His account has been neither confirmed nor denied since the case has not been examined by parliament or the courts. In 1993, Gietinger's research on his access to the previously restricted papers of Pabst, held at the Federal Military Archives, found him as central to the planning of the murder of Luxemburg and the protection of those involved.[52]

Luxemburg and Liebknecht were buried at the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery in Berlin, where socialists and communists commemorate them yearly on the second Sunday of January.

Thought[]

Revolutionary socialist democracy[]

Luxemburg professed a commitment to democracy and the necessity of revolution. Luxemburg's idea of democracy which Stanley Aronowitz calls "generalized democracy in an unarticulated form" represents Luxemburg's greatest break with "mainstream communism" since it effectively diminishes the role of the communist party, but it is in fact very similar to the views of Karl Marx ("The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves"). According to Aronowitz, the vagueness of Luxemburgian democracy is one reason for its initial difficulty in gaining widespread support. Luxemburg herself clarified her position on democracy in her writings regarding the Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union. Early on, Luxemburg attacked undemocratic tendencies present in the Russian Revolution:[53]

Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, becomes a mere semblance of life, in which only the bureaucracy remains as the active element. Public life gradually falls asleep, a few dozen party leaders of inexhaustible energy and boundless experience direct and rule. Among them, in reality only a dozen outstanding heads do the leading and an elite of the working class is invited from time to time to meetings where they are to applaud the speeches of the leaders, and to approve proposed resolutions unanimously – at bottom, then, a clique affair – a dictatorship, to be sure, not the dictatorship of the proletariat but only the dictatorship of a handful of politicians, that is a dictatorship in the bourgeois sense, in the sense of the rule of the Jacobins (the postponement of the Soviet Congress from three-month periods to six-month periods!) Yes, we can go even further: such conditions must inevitably cause a brutalization of public life: attempted assassinations, shooting of hostages, etc. (Lenin's speech on discipline and corruption.)

Luxemburg also insisted on socialist democracy:[53]

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of "justice" but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when "freedom" becomes a special privilege. [...] But socialist democracy is not something which begins only in the promised land after the foundations of socialist economy are created; it does not come as some sort of Christmas present for the worthy people who, in the interim, have loyally supported a handful of socialist dictators. Socialist democracy begins simultaneously with the beginnings of the destruction of class rule and of the construction of socialism.

Opposition to imperialist war and capitalism[]

While being critical of the politics of the Bolsheviks, Luxemburg saw the behaviour of the social democratic Second International as a complete betrayal of socialism. As she saw it at the outset of the First World War, the social democratic parties around the world betrayed the world's working class by supporting their own individual bourgeoisies in the war. This included her own Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the majority of whose delegates in the Reichstag voted for war credits.

Luxemburg opposed the sending of the working class youth of each country to what she viewed as slaughter in a war over which of the national bourgeoisies would control world resources and markets. She broke from the Second International, viewing it as nothing more than an opportunist party that was doing administrative work for the capitalists. Along with Karl Liebknecht, Luxemburg organized a strong movement in Germany with these views, but she was imprisoned and after her release killed for her work during the failed German Revolution of 1919, a revolution which the SPD violently opposed.

The Accumulation of Capital[]

The Accumulation of Capital was the only work Luxemburg published on economics during her lifetime. In the polemic, she argued that capitalism needs to constantly expand into non-capitalist areas in order to access new supply sources, markets for surplus value and reservoirs of labor.[54] According to Luxemburg, Marx had made an error in Das Kapital in that the proletariat could not afford to buy the commodities they produced and by his own criteria it was impossible for capitalists to make a profit in a closed-capitalist system since the demand for commodities would be too low and therefore much of the value of commodities could not be transformed into money. According to Luxemburg, capitalists sought to realize profits through offloading surplus commodities onto non-capitalist economies, hence the phenomenon of imperialism as capitalist states sought to dominate weaker economies. However, this was leading to the destruction of non-capitalist economies as they were increasingly absorbed into the capitalist system. With the destruction of non-capitalist economies, there would be no more markets to offload surplus commodities onto and capitalism would break down.[55]

The Accumulation of Capital was harshly criticized by both Marxist and non-Marxist economists on the grounds that her logic was circular in proclaiming the impossibility of realizing profits in a close-capitalist system and that her underconsumptionist theory was too crude.[55] Her conclusion that the limits of the capitalist system drive it to imperialism and war led Luxemburg to a lifetime of campaigning against militarism and colonialism.[54]

Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation[]

The Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation was the central feature of Luxemburg's political philosophy, wherein spontaneity is a grassroots approach to organising a party-oriented class struggle. She argued that spontaneity and organisation, are not separable or separate activities, but different moments of one political process as one does not exist without the other. These beliefs arose from her view that class struggle evolves from an elementary, spontaneous state to a higher level:[56]

The working classes in every country only learn to fight in the course of their struggles. [...] Social democracy [...] is only the advance guard of the proletariat, a small piece of the total working masses; blood from their blood, and flesh from their flesh. Social democracy seeks and finds the ways, and particular slogans, of the workers' struggle only in the course of the development of this struggle, and gains directions for the way forward through this struggle alone.

Luxemburg did not hold spontaneism as an abstraction, but she developed the Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation under the influence of mass strikes in Europe, especially the Russian Revolution of 1905.[57] Unlike the social democratic orthodoxy of the Second International, she did not regard organisation as a product of scientific-theoretic insight to historical imperatives, but as product of the working classes' struggles:[58]

Social democracy is simply the embodiment of the modern proletariat's class struggle, a struggle which is driven by a consciousness of its own historic consequences. The masses are in reality their own leaders, dialectically creating their own development process. The more that social democracy develops, grows, and becomes stronger, the more the enlightened masses of workers will take their own destinies, the leadership of their movement, and the determination of its direction into their own hands. And as the entire social democracy movement is only the conscious advance guard of the proletarian class movement, which in the words of The Communist Manifesto represent in every single moment of the struggle the permanent interests of liberation and the partial group interests of the workforce vis à vis the interests of the movement as whole, so within the social democracy its leaders are the more powerful, the more influential, the more clearly and consciously they make themselves merely the mouthpiece of the will and striving of the enlightened masses, merely the agents of the objective laws of the class movement.

Luxemburg also argued:[59]

The modern proletarian class does not carry out its struggle according to a plan set out in some book or theory; the modern workers' struggle is a part of history, a part of social progress, and in the middle of history, in the middle of progress, in the middle of the fight, we learn how we must fight. [...] That's exactly what is laudable about it, that's exactly why this colossal piece of culture, within the modern workers' movement, is epoch-defining: that the great masses of the working people first forge from their own consciousness, from their own belief, and even from their own understanding the weapons of their own liberation.

Criticism of the October Revolution[]

In an article published just before the October Revolution, Luxemburg characterized the Russian February Revolution of 1917 as a "revolution of the proletariat" and said that the "liberal bourgeoisie" were pushed to movement by the display of "proletarian power". The task of the Russian proletariat, she said, was now to end the "imperialist" world war in addition to struggling against the "imperialist bourgeoisie". The world war made Russia ripe for a socialist revolution. Therefore, "the German proletariat are also [...] posed a question of honour, and a very fateful question".[60]

In several works, including an essay written from jail and published posthumously by her last companion Paul Levi (publication of which precipitated his expulsion from the Third International), titled The Russian Revolution,[61] Luxemburg sharply criticized some Bolshevik policies such as their suppression of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918 and their policy of supporting the purported right of all national peoples to self-determination. According to Luxemburg, the Bolsheviks' strategic mistakes created tremendous dangers for the Revolution such as its bureaucratisation.

Her sharp criticism of the October Revolution and the Bolsheviks was lessened insofar as she compared the errors of the Revolution and of the Bolsheviks with the "complete failure of the international proletariat".[62]

Bolshevik theorists such as Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky responded to this criticism by arguing that Luxemburg's notions were classical Marxist ones, but they could not be applied to Russia of 1917. They stated that the lessons of actual experience such as the confrontation with the bourgeois parties had forced them to revise the Marxian strategy. As part of this argument, it was pointed out that after Luxemburg herself got out of jail, she was also forced to confront the National Assembly in Germany, a step they compared with their own conflict with the Russian Constituent Assembly.[63]

In this erupting of the social divide in the very lap of bourgeois society, in this international deepening and heightening of class antagonism lies the historical merit of Bolshevism, and with this feat – as always in large historic connections – the particular mistakes and errors of the Bolsheviks disappear without trace.

After the October Revolution, it becomes the "historic responsibility" of the German workers to carry out a revolution for themselves and thereby end the war.[64] When the German Revolution also broke out, Luxemburg immediately began agitating for a social revolution:[65]

The abolition of the rule of capital, the realization of a socialist social order – this, and nothing less, is the historical theme of the present revolution. It is a formidable undertaking, and one that will not be accomplished in the blink of an eye just by the issuing of a few decrees from above. Only through the conscious action of the working masses in city and country can it be brought to life, only through the people's highest intellectual maturity and inexhaustible idealism can it be brought safely through all storms and find its way to port.

In her later work The Russian Tragedy, Luxemburg blamed many of the perceived failures of the Bolsheviks on the lack of a socialist uprising in Germany:

The Bolsheviks have certainly made a number of mistakes in their policies and are perhaps still making them – but where is the revolution in which no mistakes have been made! The notion of a revolutionary policy without mistakes, and moreover, in a totally unprecedented situation, is so absurd that it is worthy only of a German schoolmaster. If the so-called leaders of German socialism lose their so-called heads in such an unusual situation as a vote in the Reichstag, and if their hearts sink into their boots and they forget all the socialism they ever learned in situation in which the simple abc of socialism clearly pointed the way – could one expect a party caught up in a truly thorny situation, in which it would show the world new wonders, not to make mistakes?

Luxemburg further stated:[66]

The awkward position that the Bolsheviks are in today, however, is, together with most of their mistakes, a consequence of basic insolubility of the problem posed to them by the international, above all the German, proletariat. To carry out the dictatorship of the proletariat and a socialist revolution in a single country surrounded by reactionary imperialist rule and in the fury of the bloodiest world war in human history – that is squaring the circle. Any socialist party would have to fail in this task and perish – whether or not it made self-renunciation the guiding star of its policies.

Luxemburg also considered a socialist uprising in Germany to be the solution to the problems the Bolsheviks faced:[66]

There is only one solution to the tragedy in which Russia is caught up: an uprising at the rear of German imperialism, the German mass rising, which can signal the international revolution to put an end to this genocide. At this fateful moment, preserving the honour of the Russian Revolution is identical with vindicating that of the German proletariat and of international socialists.

Epitaph on her death[]

Despite the criticism, Lenin praised Luxemburg after her death as an "eagle" of the working class:[67]

But in spite of her mistakes she was – and remains for us – an eagle. And not only will communists all over the world cherish her memory, but her biography and her complete works (the publication of which the German communists are inordinately delaying, which can only be partly excused by the tremendous losses they are suffering in their severe struggle) will serve as useful manuals for training many generations of communists all over the world. 'Since 4 August 1914, German Social-Democracy has been a stinking corpse' – this statement will make Rosa Luxemburg's name famous in the history of the international working class movement.

Trotsky also publicly mourned Luxemburg's death:[68]

We have suffered two heavy losses at once which merge into one enormous bereavement. There have been struck down from our ranks two leaders whose names will be for ever entered in the great book of the proletarian revolution: Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. They have perished. They have been killed. They are no longer with us!

In later years, Trotsky frequently defended Luxemburg, claiming that Joseph Stalin had vilified her.[9] In the article Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!, Trotsky criticized Stalin for this despite what Trotsky perceived as Luxemburg's theoretical errors, writing: "Yes, Stalin has sufficient cause to hate Rosa Luxemburg. But all the more imperious therefore becomes our duty to shield Rosa's memory from Stalin's calumny that has been caught by the hired functionaries of both hemispheres, and to pass on this truly beautiful, heroic, and tragic image to the young generations of the proletariat in all its grandeur and inspirational force".[69]

Quotations[]

- Luxemburg's best-known quotation "Freiheit ist immer nur Freiheit des anders Denkenden" (sometimes translated as "Freedom is always the freedom of dissenters") is an excerpt from the following passage:[70]

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of a party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always the freedom of the one who thinks differently. Not because of the fanaticism of "justice", but rather because all that is instructive, wholesome, and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effects cease to work when "freedom" becomes a privilege.

- The capitalist state of society is doubtless a historic necessity, but so also is the revolt of the working class against it – the revolt of its gravediggers. (April 1915)

- Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, becomes a mere semblance of life, in which only the bureaucracy remains as the active element.[71]

- For us there is no minimal and no maximal program; socialism is one and the same thing: this is the minimum we have to realize today.[72]

- Today, we face the choice exactly as Friedrich Engels foresaw it a generation ago: either the triumph of imperialism and the collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration – a great cemetery. Or the victory of socialism, that means the conscious active struggle of the international proletariat against imperialism and its method of war.[73]

- Most of those bourgeois women who act like lionesses in the struggle against "male prerogatives" would trot like docile lambs in the camp of conservative and clerical reaction if they had suffrage.[74] (Luxemburg's famous observation and critique of liberal feminism)

- Imperialism is the political expression of the accumulation of capital in its competitive struggle for what remains still open of the non-capitalist environment.[75]

Last words: belief in revolution[]

Luxemburg's last known words written on the evening of her murder were about her belief in the masses and what she saw as the inevitability of a triumphant revolution:[76]

The contradiction between the powerful, decisive, aggressive offensive of the Berlin masses on the one hand and the indecisive, half-hearted vacillation of the Berlin leadership on the other is the mark of this latest episode. The leadership failed. But a new leadership can and must be created by the masses and from the masses. The masses are the crucial factor. They are the rock on which the ultimate victory of the revolution will be built. The masses were up to the challenge, and out of this "defeat" they have forged a link in the chain of historic defeats, which is the pride and strength of international socialism. That is why future victories will spring from this "defeat." "Order prevails in Berlin!" You foolish lackeys! Your "order" is built on sand. Tomorrow the revolution will "rise up again, clashing its weapons," and to your horror it will proclaim with trumpets blazing: I was, I am, I shall be!

Commemoration[]

The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution notes that idolization of Luxemburg and Liebnecht is an important tradition of German far-left extremism.[3] Luxemburg and Liebnecht were idolized as communist martyrs by the East German communist regime and are still idolized by the East German communist party's successor party The Left.[3]

In the former East Germany and East Berlin, various places were named for Luxemburg by the East German communist party. These include the Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz and a U-Bahn station which were located in East Berlin during the Cold War. The engraving on the nearby pavement reads "Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein" ("I was, I am, I will be"). The Volksbühne (People's Theatre) is on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz.

Dresden has a street and streetcar stop named after Luxemburg. The names remained unchanged after the German reunification.

During the Polish People's Republic in Warsaw's Wola district, a manufacturing facility of electric lamps was established and named after Luxemburg.

In 1919, Bertolt Brecht wrote the poetic memorial Epitaph honouring Luxemburg and Kurt Weill set it to music in The Berlin Requiem in 1928:

Red Rosa now has vanished too,

And where she lies is hid from view.

She told the poor what life's about,

And so the rich have rubbed her out.

May she rest in peace.

The British New Left historian Isaac Deutscher wrote of Luxemburg: "In her assassination Hohenzollern Germany celebrated its last triumph and Nazi Germany its first".

Opponents of Marxism had a very different interpretation of Luxemburg's murder. Anti-communist Russian refugees occasionally expressed envy for the Freikorps' success in defeating the Spartacus League. In a 1922 conversation with Count Harry Kessler, one such refugee lamented:[77]

Infamous, that fifteen thousand Russian officers should have let themselves be slaughtered by the Revolution without raising a hand in self-defense! Why didn't they act like the Germans, who killed Rosa Luxemburg in such a way that not even a smell of her has remained?

There is also a monument in Luxembourg for "Lady Rosa" done by Sanja Iveković.

In Barcelona, there are terraced gardens named in her honor. In Madrid, there is a street and several public schools and associations named after Luxemburg. Other Spanish cities including Gijón, Getafe or Arganda del Rey have streets named after her.

At the edge of the Tiergarten on the Katharina-Heinroth-Ufer which runs between the southern bank of the Landwehr Canal and the bordering Zoologischer Garten (Zoological Garden), a memorial has been installed by a private initiative. On the memorial, the name Rosa Luxemburg appears in raised capital letters, marking the spot where her body was thrown into the canal by Freikorps troops.

The famous Monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, originally named Monument to the November Revolution (Revolutionsdenkmal) which was built in 1926 in Berlin-Lichtenberg[78] and destroyed in 1935, was designed by pioneering modernist and later Bauhaus director Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The memorial took the form of a suprematist composition of brick masses. Van der Rohe said: "As most of these people [Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and other fallen heroes of the Revolution] were shot in front of a brick wall, a brick wall would be what I would build as a monument". The commission came about through the offices of Eduard Fuchs, who showed a proposal featuring Doric columns and medallions of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, prompting Mies' laughter and the comment "That would be a good monument for a banker". The monument was destroyed by the Nazis after they took power.

Two small international networks based on her political thought characterize themselves as Luxemburgists, namely the Communist Democracy (Luxemburgist) founded in 2005 and the International Luxemburgist Network founded in 2008. Feminists and Trotskyists as well as leftists in Germany especially show interest in Luxemburg's ideas. Distinguished modern Marxist thinkers such as Ernest Mandel, who has even been characterised as Luxemburgist, have seen Luxemburg's thought as a corrective to revolutionary theory.[79] In 2002, ten thousand people marched in Berlin for Luxemburg and Liebknecht and another 90,000 people laid carnations on their graves.[80]

Annual demonstration[]

In the city of Berlin a Liebknecht-Luxemburg Demonstration, shortly LL-Demo, is organized annually in the month of January around the date of their death. This demonstration takes place on the second weekend of the month in Berlin-Friedrichshain, starting near the Frankfurter Tor to the central cemetery Friedrichsfelde, also known as the Gedenkstätte der Sozialisten (Socialist Memorial).[81] During the East Germany era, the event was said to be orchestrated as a mere show event for Socialist Unity Party of Germany celebrities, broadcast live on its state television.[82]

In January 2019, the German left-wing parties commemorated at the occasion of this demonstration the 100th anniversary of the murder on Luxemburg and Liebknecht.[83][84][85]

In popular culture and literature[]

Due to Luxemburg's importance in the development of theories of Marxist humanist thought, the role of democracy and mass action to achieve international socialism as a pioneering feminist and as a martyr to her cause, she has become a minor iconic figure,[86][87] celebrated with references in popular culture.

- Bulgarian writer Hristo Smirnenski, who praised communist ideology, wrote the poem "Rosa Luxemburg" in tribute to Luxemburg in 1923.[88]

- Rosa Luxemburg (1986),[89][90][91][92] directed by Margarethe von Trotta. The film, which stars Barbara Sukowa as Luxemburg, was the winner of the Best Actress Award at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival.

- In 1992, the Quebec painter Jean-Paul Riopelle realized a fresco composed of thirty paintings entitled Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg.[93][94] It is on permanent display at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Quebec in Quebec City.

- Luxemburg influences the lives of several characters in William T. Vollmann's 2005 historical fiction Europe Central.[95]

- Rosa, a novel by Jonathan Rabb (2005), gives a fictional account of the events leading to Luxemburg's murder.

- The heroine in the novel Burger's Daughter (1979) by Nadine Gordimer is named Rosa Burger in homage to Luxemburg.[96]

- Harry Turtledove's Southern Victory series of alternate history novels contains an American socialist politician character named Flora Hamburger, a reference to the real historical personage of Luxemburg.

- Simon Louvish's 1994 alternate history novel The Resurrections (from Four Walls Eight Windows, a revision of Resurrections from the Dustbin of History: A Political Fantasy), had Luxemburg and Liebknecht avoid death, their revolution becoming reality in 1923 when a failed Reichstag coup by Gregor and Otto Strasser (plotted by the Black Reichswehr's Bruno Ernst Buchrucker) killed Gustav Stresemann, Wilhelm Cuno, Hans von Seeckt and 17 deputies followed by the Marxists creating a Berlin commune whose squads executed the Strassers and any Nazis not already in exile, the Reichswehr then disarming the Freikorps and accepting a German Soviet Republic's legitimacy, with Liebknecht as Minister of the Interior.[97]

- The pet tortoise at Balliol College, Oxford was named in honour of Luxemburg. She went missing in spring 2004.[98][99]

- A song on the 1997 album Morskaya of the Russian rock band Mumiy Troll is titled in her honor.[100]

- Langston Hughes alludes to her death in the poem "Kids Who Die" in the line "Or the rivers where you're drowned like Liebknecht".[101]

- Luxemburg appears in Karl and Rosa, a novel by Alfred Döblin.[102]

- She also appears in the novel Time and Time Again by Ben Elton.[103]

- Red Rosa is a graphic novelization by Kate Evans.[104]

- German artist Max Beckmann in his post WWI lithograph Das Martyrium depicts Luxemburg’s murder as a sexual assault, her clothes torn, her underwear revealed, one soldier fondling her left breast; another smirking while aiming his rifle butt at her right breast, the hotel manager holding her legs apart. There is no historical justification for this depiction. Tellini in Woman’s Art Journal 1997 argues both the sensationalising aspect of graphic sexual assault as well as the artist’s misogyny were probably responsible.[105]

- The song Strange Time To Bloom, written by Nancy Kerr, "For Rosa Luxemburg, March 1871 – January 1919" appears on the 2019 Melrose Quartet album The Rudolph Variations.[106]

- The feminist magazine Lux, which began in 2020, says that it is named for Rosa Luxemburg, describing her as "one of the most creative minds to remake the socialist tradition."[107]

Body identification controversy[]

On 29 May 2009, Spiegel online, the internet branch of the news magazine Der Spiegel, reported the recently considered possibility that someone else's remains had mistakenly been identified as Luxemburg's and buried as hers.[48]

The forensic pathologist Michael Tsokos, head of the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences at the Berlin Charité, discovered a preserved corpse lacking head, feet, or hands in the cellar of the Charité's medical history museum. He found the corpse's autopsy report suspicious and decided to perform a CT scan on the remains. The body showed signs of having been waterlogged at some point and the scans showed that it was the body of a woman of 40–50 years of age who suffered from osteoarthritis and had legs of differing length. At the time of her murder, Luxemburg was 47 years old and suffering from a congenital dislocation of the hip that caused her legs to have different lengths. A laboratory in Kiel also tested the corpse using radiocarbon dating techniques and confirmed that it dated from the same period as Luxemburg's murder.

The original autopsy, performed on 13 June 1919 on the body that was eventually buried at Friedrichsfelde, showed certain inconsistencies that supported Tsokos' hypothesis. The autopsy explicitly noted an absence of hip damage and stated that there was no evidence that the legs were of different lengths. Additionally, the autopsy showed no traces on the upper skull of the two blows by rifle butt inflicted upon Luxemburg. Finally, while the 1919 examiners noted a hole in the corpse's head between left eye and ear, they did not find an exit wound or the presence of a bullet within the skull.

Assistant pathologist Paul Fraenckel appeared to doubt at the time that the corpse he had examined was Luxemburg's and in a signed addendum distanced himself from his colleague's conclusions. This addendum and the inconsistencies between the autopsy report and the known facts persuaded Tsokos to examine the remains more closely. According to eyewitnesses, when Luxemburg's body was thrown into the canal, weights were wired to her ankles and wrists. These could have slowly severed her extremities in the months her corpse spent in the water which would explain the missing hands and feet issue.[48]

Tsokos realized that DNA testing was the best way to confirm or deny the identity of the body as Luxemburg's. His team had initially hoped to find traces of the DNA on old postage stamps that Luxemburg had licked, but it transpired that Luxemburg had never done this, preferring to moisten stamps with a damp cloth. The examiners decided to look for a surviving blood relative and in July 2009 the German Sunday newspaper Bild am Sonntag reported that a great-niece of Luxemburg had been located – a 79-year-old woman named Irene Borde. She donated strands of her hair for DNA comparison.[108]

In December 2009, Berlin authorities seized the corpse to perform an autopsy before burying it in Luxemburg's grave.[109] The Berlin Public Prosecutor's office announced in late December 2009 that while there were indications that the corpse was Luxemburg's, there was not enough evidence to provide conclusive proof. In particular, DNA extracted from the hair of Luxemburg's niece did not match that belonging to the cadaver. Tsokos had earlier said that the chances of a match were only 40%. The remains were to be buried at an undisclosed location while testing was to continue on tissue samples.[110]

Works[]

- The Accumulation of Capital, translated by Agnes Schwarzschild in 1951. Routledge Classics 2003 edition. Originally published as Die Akkumulation des Kapitals in 1913.

- The Accumulation of Capital: an Anticritique, written in 1915.

- Gesammelte Werke (Collected Works), 5 volumes, Berlin, 1970–1975.

- Gesammelte Briefe (Collected Letters), 6 volumes, Berlin, 1982–1997.

- Politische Schriften (Political Writings), edited and with preface by Ossip K. Flechtheim, 3 volumes, Frankfurt am Main, 1966 ff.

- The Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg, 14 volumes, London and New York, 2011.

- The Rosa Luxemburg Reader, edited by Peter Hudis and Kevin B. Anderson.

Writings[]

This is a list of selected writings:

| Writing | Year | Text | Translator | Year of English publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Industrial Development of Poland | 1898 | English | Tessa DeCarlo | 1977 |

| In Defense of Nationality | 1900 | English | Emal Ghamsharick | 2014 |

| Social Reform or Revolution? | 1900 | English | ||

| The Socialist Crisis in France | 1901 | English | ||

| Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy | 1904 | English | ||

| The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions | 1906 | English | Patrick Lavin | 1906 |

| The National Question | 1909 | English | ||

| Theory & Practice | 1910 | English | ||

| The Accumulation of Capital | 1913 | English | Agnes Schwarzschild | 1951 |

| The Accumulation of Capital: An Anti-Critique | 1915 | English | ||

| The Junius Pamphlet | 1915 | English | ||

| The Russian Revolution | 1918 | English | ||

| The Russian Tragedy | 1918 | English |

Speeches[]

| Speech | Year | Transcript |

|---|---|---|

| Speeches to Stuttgart Congress | 1898 | English |

| Speech to the Hanover Congress | 1899 | English |

| Speech to the Nuremberg Congress of the German Social Democratic Party | 1908 | English |

See also[]

- Proletarian internationalism

- Rosa Luxemburg Foundation

- List of peace activists

Citations[]

- ^ Frederik Hetmann: Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben für die Freiheit, p. 308.

- ^ Leszek Kołakowski ([1981], 2008), Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. 2: The Golden Age, W. W. Norton & Company, Ch III: "Rosa Luxemburg and the Revolutionary Left".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gedenken an Rosa Luxemburg und Karl Liebknecht – ein Traditionselement des deutschen Linksextremismus (PDF). BfV-Themenreihe. Cologne: Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2017.

- ^ Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. pp. 7–29. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Winkler, Anna (24 June 2019). "Róża Luksemburg. Pierwsza Polka z doktoratem z ekonomii". ciekawostkihistoryczne.pl. CiekawostkiHistoryczne.pl. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Winczewski, Damian (18 April 2020). "Prawdziwe oblicze Róży Luksemburg?". histmag.org. Histmag.org. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Glossary of People: L". Marxists.org. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Matrikeledition". Matrikel.uzh.ch. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Merrick, Beverly G. (1998). "Rosa Luxemburg: A Socialist With a Human Face". Center for Digital Discourse and Culture at Virginia Tech University. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ J. P. Nettl, Rosa Luxemburg, Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Annette Insdorf (31 May 1987). "Rosa Luxemburg: More Than a Revolutionary". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. p. 18. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luksemburg, Róża (July 1893). "O wynaradawianiu (Z powodu dziesięciolecia rządów jen.-gub. Hurki)". Sprawa Robotnicza.

- ^ Weber, Hermann; Herbst, Andreas. "Luxemburg, Rosa". Handbuch der Deutschen Kommunisten. Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin & Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Luise Kautsky (editor-compiler) (2017). Rosa Luxemburg: Briefe aus dem Gefängnis: Denken und Erfahrungen der internationalen Revolutionärin. Information is taken not from the letters themselves but from a lengthy biographical essay which appears at the end of the volume. Musaicum Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-80-7583-324-2.

- ^ Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. p. 13. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. p. 14. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. p. 15. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. p. 16. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.). O rewolucji: 1905, 1917. Instytut Wydawniczy „Książka i Prasa”. p. 17. ISBN 9788365304599.

- ^ Waters, p. 12.

- ^ Nettl, p. 383; Waters, p. 13.

- ^ "Selbst im Gefängnis Trost für andere". Die Zeit (online). 5 October 1984. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Heute war mir Dein süßer Brief ein solcher Trost" (PDF). Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Gesellschaftsanalyse und politische Bildung e. V., Berlin. p. 31. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Rosa Luxemburg: Gesammelte Briefe. Vol. 2, 5 and 6.

- ^ Rowbotham, Sheila (5 March 2011). "The revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Waters, p. 20.

- ^ Revolutionary Rosa: The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg. Reviewed by Irene Gammel for the Globe and Mail.

- ^ Waters, p. 19.

- ^ Rauba, Ryszard (28 September 2011). "Ryszard Rauba: Wątek niemiecki w zapomnianej korespondencji Róży Luksemburg". 1917.net. Instytut Politologii, Uniwersytet Zielonogórski. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Weitz, Eric D. (1994). "'Rosa Luxemburg Belongs to Us!'". German Communism and the Luxemburg Legacy. Central European History (27: 1), pp. 27–64.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kate Evans, Red Rosa: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg, New York, Verso, 2015

- ^ Weitz, Eric D. (1997). Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paul Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg, London: Haymarket Books, 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b Waters, pp. 18–19.

- ^ "The Russian Revolution, Chapter 6: The Problem of Dictatorship". Marxists.org. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Die Krise der Sozialdemokratie (Junius-Broschüre)".

- ^ von Hellfeld, Matthias (16 November 2009). "Long Live the Republic – 9 November 1918". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Luban, Ottokar (2017). The Role of the Spartacist Group after 9 November 1918 and the Formation of the KPD In Hoffrogge, Ralf; LaPorte, Norman (eds.). Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933. London: Lawrence & Wishart. pp. 45–65.

- ^ Nettl, J. P. Rosa Luxemburg. Vol. 1. p. 131. Waters, Mary-Alice Waters (ed.). Rosa Luxemburg Speaks. p. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones 2016, p. 193.

- ^ Jones 2016, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Jones 2016, p. 210.

- ^ Jones 2016, p. 203.

- ^ Jones 2016, p. 207.

- ^ Jones 2016, p. 209.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Thadeusz, Frank (29 May 2009). "Revolutionary Find: Berlin Hospital May Have Found Rosa Luxemburg's Corpse". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Wroe, David (18 December 2009). "Rosa Luxemburg Murder Case Reopened". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Nettl, J. P. (1969). Rosa Luxemburg. Oxford University Press. pp. 487–490.

- ^ "Martyrdom of Liebknecht and Luxemburg". Revolutionarydemocracy.org. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Gietinger 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Russian Revolution, Chapter 6".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scott, Helen (2008). "Introduction to Rosa Luxemburg". The Essential Rosa Luxemburg: Reform or Revolution and The Mass Strike. By Luxemburg, Rosa. Chicago: Haymarket Books. p. 18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kolakowski, Leszek (2008). Main Currents of Marxism. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 407–415.

- ^ In a Revolutionary Hour: What Next?. Collected Works (1: 2). p. 554.

- ^ Rosa Luxemburg at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ The Political Leader of the German Working Classes. Collected Works. Vol. 2. p. 280.

- ^ The Politics of Mass Strikes and Unions. Collected Works. Vol. 2. p. 465.

- ^ The Politics of Mass Strikes and Unions. Collected Works. Vol. 2. p. 245.

- ^ "The Nationalities Question in the Russian Revolution (Rosa Luxemburg, 1918)". Libcom.org. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ On the Russian Revolution. GW 4. p. 334.

- ^ Fragment on War, National Questions, and Revolution. Collected Works. Vol. 4, p. 366.

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa. The Historic Responsibility. GW 4. p. 374.

- ^ The Beginning. Collected Works. Vol. 4. p. 397.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Luxemburg, Rosa. "Rosa Luxemburg: The Russian Tragedy (September 1918)". Marxists.org. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Larsen, Patrick (15 January 2009). "Ninety Years after the Murder of Rosa Luxemburg: Lessons of the Life of a Revolutionary". International Marxist Tendency. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1919). "Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg". International Marxist Tendency. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (June 1932). "Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!". International Marxist Tendency. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Die russische Revolution. Eine kritische Würdigung" (1920). Berlin. p. 109. Collected Works (1983). Dietz Verlag Berlin (East). Vol. 4. p. 359.

- ^ The Russian Revolution. Chapter 6. Rosa Luxemburg Internet Archive.

- ^ Our Program and the Political Situation. Rosa Luxemburg Internet Archive.

- ^ The Junius Pamphlet. Chapter 1. In the Rosa Luxemburg Internet Archive.

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa. "Rosa Luxemburg: Women's Suffrage and Class Struggle (1912)". Marxists.org. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa. "The Accumulation of Capital (Chap.31)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa. Order Reigns in Berlin. Collected Works. Vol. 4. p. 536. Rosa Luxemburg Internet Archive.

- ^ Kessler, Harry Graf (1990). Berlin in Lights: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler (1918–1937). New York: Grove Press. Tuesday 28 March 1922.

- ^ "Mies van der Rohe". Facebook.com. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Achacar, Gilbert. "The Actuality of Ernest Mandel".

- ^ "Workers World Jan. 31, 2002: Berlin events honor left-wing leaders".

- ^ Meintz, Rene (13 January 2019). "Liebknecht-Luxemburg-Demonstration". Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg-Portal.

- ^ "Luxemburg-Liebknecht-Demonstration". Jugendopposition in der DDR.

- ^ "Gloomy German left remembers murdered Rosa Luxemburg". www.thelocal.de. 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Berlin: 15,000 Rally to Remember the 100th Anniversary of the Assassination Of Communists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht". 13 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "What can we learn from Rosa Luxemburg, 100 years after her murder?". www.thelocal.de. 15 January 2019.

- ^ "German corpse 'may be Luxemburg'". BCC News. 29 May 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "14 Badass Historical Women To Name Your Daughters After". BuzzFeed. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ hakki (7 October 2015). "Hristo Smirnenski Kimdir?". Hakkında Bilgi (in Turkish). Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Die Geduld der Rosa Luxemburg (1986), retrieved 30 March 2019

- ^ Rosa Luxemburg, retrieved 30 March 2019

- ^ "Rosa Luxemburg (Die Geduld der Rosa Luxemburg)". Independent Cinema Office. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Platypus Affiliated Society, Rosa Luxemburg, retrieved 30 March 2019

- ^ "Jean-Paul Riopelle "Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg"". Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ). Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Québec, Musée national des beaux-arts du. "Mitchell | Riopelle – Nothing in Moderation". Newswire.ca. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Vollmann, William T. (2005). Europe central. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0670033928. OCLC 56911959.

- ^ Niedziałek, Ewe (2018). "The Desire of Nowhere – Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter in a Trans-cultural Perspective". Colloquia Humanistica. Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk (7): 40–41. doi:10.11649/ch.2018.003.

- ^ Louvish, Simon. (1994). The resurrections : a novel. Louvish, Simon. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 978-1568580142. OCLC 30158761.

- ^ Balliol College, Oxford

- ^ "Balliol made them". The Daily Telegraph. London. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Morskaya (Nautical), by Mumiy Troll". Mumiy Troll. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ "Langston Hughes – Kids Who Die". Genius. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Döblin, Alfred (1983). Karl and Rosa : a novel (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Fromm International Pub. Corp. ISBN 978-0880640107. OCLC 9894460.

- ^ Elton, Ben. Time and time again (First U.S. ed.). New York. ISBN 9781250077066. OCLC 898419165.

- ^ "The Radical Life of Rosa Luxemburg". The Nation. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Tellini, Ute L. (1997). "Max Beckmann's "Tribute" to Rosa Luxemburg". Woman's Art Journal. 18 (2): 22–26. doi:10.2307/1358547. ISSN 0270-7993. JSTOR 1358547.

- ^ "Melrose Quartet". Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "About – Lux Magazine".

- ^ "DNA of Great-Niece May Help Identify Headless Corpse". Spiegel Online. SpiegelOnline. 21 July 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ "Berlin Authorities Seize Corpse for Pre-Burial Autopsy". Spiegel Online. SpiegelOnline. 17 December 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ^ "Rosa Luxemburg "floater" released for burial after 90 years". Lost in Berlin. Salon.com. 30 December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

Bibliography[]

- Basso, Lelio (1975). Rosa Luxemburg: A Reappraisal. London.

- Bronner, Stephen Eric (1984). Rosa Luxemburg: A Revolutionary for Our Times.

- Cliff, Tony (1980) [1959]. "Rosa Luxemburg". International Socialism. London (2/3).

- Dunayevskaya, Raya (1982). Rosa Luxemburg, Women's Liberation, and Marx's Philosophy of Revolution. New Jersey.

- Ettinger, Elzbieta (1988). Rosa Luxemburg: A Life.

- Frölich, Paul (1939). Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work.

- Geras, Norman (1976). The Legacy of Rosa Luxemburg.

- Gietinger, Klaus (1993). Eine Leiche im Landwehrkanal – Die Ermordung der Rosa L. (A Corpse in the Landwehrkanal – The Murder of Rosa L.) (in German). Berlin: Verlag. ISBN 978-3-930278-02-2.

- Gietinger, Klaus (2019). The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg). Translated by Halborn, L. New York: Verso. ISBN 978-1-78873-448-6.

- Hetmann, Frederik (1980). Rosa Luxemburg: Ein Leben für die Freiheit. Frankfurt. ISBN 978-3-596-23711-1.

- Jones, Mark (2016). Founding Weimar: Violence and the German Revolution of 1918–1919. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-11512-5.

- Kemmerer, Alexandra (2016), "Editing Rosa: Luxemburg, the Revolution, and the Politics of Infantilization". European Journal of International Law, Vol. 27 (3), 853–864. doi:10.1093/ejil/chw046

- Hudis, Peter; Anderson (eds.), Kevin B. (2004). "The Rosa Luxemburg Reader". Monthly Review.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kulla, Ralf (1999). Revolutionärer Geist und Republikanische Freiheit. Über die verdrängte Nähe von Hannah Arendt und Rosa Luxemburg. Mit einem Vorwort von Gert Schäfer. Diskussionsbeiträge des Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft der Universität Hannover. Band 25. Hannover: Offizin Verlag. ISBN 978-3-930345-16-8.

- Nettl, J. P. (1966). Rosa Luxemburg. It is long considered the definitive biography of Luxemburg.

- Shepardson, Donald E. (1996). Rosa Luxemburg and the Noble Dream. New York.

- Waters, Mary-Alice (1970). Rosa Luxemburg Speaks. London: Pathfinder. ISBN 9780873481465.

- Weitz, Eric D. (1997). Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Priestand, David (2009). Red Flag: A History of Communism. New York: Grove Press.

- Weitz, Eric D. (1994). "'Rosa Luxemburg Belongs to Us!'" German Communism and the Luxemburg Legacy. Central European History (27: 1). pp. 27–64.

- Evans, Kate (2015). Red Rosa: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg. New York: Verso.

- Luban, Ottokar (2017). The Role of the Spartacist Group after 9 November 1918 and the Formation of the KPD. In Hoffrogge, Ralf; LaPorte, Norman (eds.). Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933. London: Lawrence & Wishart. pp. 45–65.

External links[]

- Rosa Luxemburg at the Marxists Internet Archive

- Rosa Luxemburg Foundation

- Jörn Schütrumpf Rosa Luxemburg or: The Price of Freedom

- Socialist Studies Special Issue on Rosa Luxembourg

- Rosa Luxemburg: Revolutionary Hero

- Rosa Luxemburg: A Socialist With a Human Face

- Rosa Luxemburg: "The War and the Workers" (1916)

- German Corpse 'may be Luxemburg', BBC News, 29 May 2009

- Revolutionary Rosa: The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg, reviewed by Irene Gammel for the Globe and Mail

- Luxemburg-Jacob papers at the Online Archive of California

- Works by Rosa Luxemburg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Rosa Luxemburg at Internet Archive

- Works by Rosa Luxemburg at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Trotsky on Luxemburg and Liebknecht at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 October 2009)

- Newspaper clippings about Rosa Luxemburg in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Rosa Luxemburg

- 1871 births

- 1919 deaths

- People from Zamość

- People from Lublin Governorate

- Polish Ashkenazi Jews

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Germany

- German people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania politicians

- Social Democratic Party of Germany politicians

- Imperialism studies

- Independent Social Democratic Party politicians

- Communist Party of Germany politicians

- 19th-century German writers

- 19th-century Polish politicians

- 19th-century philosophers

- 19th-century German women writers

- 20th-century German writers

- 20th-century Polish philosophers

- 20th-century German women writers

- Anti-poverty advocates

- Communist books

- Communist women writers

- German Ashkenazi Jews

- German Marxists

- German anti-capitalists

- German anti–World War I activists

- German revolutionaries

- German women in politics

- German women philosophers

- Jewish German politicians

- Jewish philosophers

- Jewish socialists

- Marxist theorists

- Marxist writers

- People of the German Revolution of 1918–1919

- People of the Weimar Republic

- Polish Marxists

- Polish revolutionaries

- Polish women in politics

- University of Zurich alumni

- German women economists

- Women religious writers

- Works by Rosa Luxemburg

- Socialist economists

- 19th-century Polish women writers

- 19th-century Polish writers

- Assassinated German politicians

- Assassinated Jews

- Assassinated Polish politicians

- Executed activists

- Executed German women

- Executed Polish women

- German murder victims

- People murdered in Berlin

- 20th-century German philosophers

- Political party founders

- Polish people murdered abroad

- Deaths by firearm in Germany