Banana republic

In political science, the term banana republic describes a politically unstable country with an economy dependent upon the exportation of a limited-resource product, such as bananas or minerals. In 1904, the American author O. Henry coined the term to describe Honduras and neighbouring countries under economic exploitation by U.S. corporations, such as the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita Brands International).[1] Typically, a banana republic has a society of extremely stratified social classes, usually a large impoverished working class and a ruling class plutocracy, composed of the business, political, and military elites of that society.[2] The ruling class controls the primary sector of the economy by way of the exploitation of labor;[3] thus, the term banana republic is a pejorative descriptor for a servile oligarchy that abets and supports, for kickbacks, the exploitation of large-scale plantation agriculture, especially banana cultivation.[3]

A banana republic is a country with an economy of state capitalism, whereby the country is operated as a private commercial enterprise for the exclusive profit of the ruling class. Such exploitation is enabled by collusion between the state and favored economic monopolies, in which the profit, derived from the private exploitation of public lands, is private property, while the debts incurred thereby are the financial responsibility of the public treasury. Such an imbalanced economy remains limited by the uneven economic development of town and country and usually reduces the national currency into devalued banknotes (paper money), rendering the country ineligible for international development credit.[4]

Etymology[]

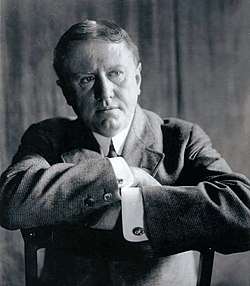

In the 19th century, the American writer O. Henry (William Sydney Porter, 1862–1910) coined the term banana republic to describe the fictional Republic of Anchuria in the book Cabbages and Kings (1904),[1] a collection of thematically related short stories inspired by his experiences in Honduras, where he lived for six months until January 1897, hiding in a hotel while he was wanted in the U.S. for embezzlement from a bank.[5]

In the early 20th century, the United Fruit Company, a multinational American corporation, was instrumental in the creation of the banana republic phenomenon.[6][7] Together with other American corporations, such as the Cuyamel Fruit Company, and with occasional support from the United States government, the corporations created the political, economic, and social circumstances that established banana republics in Central American countries such as Honduras and Guatemala.[8]

Origin[]

The history of the banana republic began with the introduction of the banana fruit to the U.S. in 1870, by Lorenzo Dow Baker, captain of the schooner Telegraph, who bought bananas in Jamaica and sold them in Boston at a 1,000% profit.[9] The banana proved popular with Americans, as a nutritious tropical fruit that was less expensive than locally grown fruit in the U.S., such as apples; in 1913, 25 cents (equivalent to $6.55 in 2020) bought a dozen bananas, but only two apples.[10] In 1873, to produce food for their railroad workers, the American railroad tycoons Henry Meiggs and his nephew, Minor C. Keith, established banana plantations along the railroads they built in Costa Rica; recognizing the profitability of exporting bananas, they began exporting the fruit to the Southeastern U.S.[10]

In the mid-1870s, to manage the new industrial-agriculture business enterprise in the countries of Central America, Keith founded the Tropical Trading and Transport Company: one-half of what would later become the United Fruit Company (UFC), later Chiquita Brands International, created in 1899 by merger with the Boston Fruit Company, and owned by Andrew Preston. By the 1930s, the international political and economic tensions created by the United Fruit Company enabled the corporation to control 80–90% of the banana business in the U.S.[11]

By the late 19th century, three American multinational corporations (the United Fruit Company, the Standard Fruit Company, and the Cuyamel Fruit Company) dominated the cultivation, harvesting, and exportation of bananas, and controlled the road, rail, and port infrastructure of Honduras. In the northern coastal areas near the Caribbean Sea, the Honduran government ceded to the banana companies 500 hectares per kilometre (2,000 acre/mi) of a laid railroad, despite there being neither passenger nor freight railroad service to Tegucigalpa, the capital city. Among the Honduran people, the United Fruit Company was known as El Pulpo ("The Octopus" in English), because its influence pervaded Honduran society, controlled their country's transport infrastructure, and manipulated Honduran national politics with anti-labor violence.[12]

In 1924, despite the UFC monopoly, the Vaccaro Brothers established the Standard Fruit Company (later the Dole Food Company) to export Honduran bananas to the U.S. port of New Orleans. The fruit-exporting corporations kept U.S. prices low by legalistic manipulation of Latin American national land use laws to cheaply buy large tracts of prime agricultural land for corporate banana plantations in the republics of the Caribbean Basin, the Central American isthmus, and tropical South America; the American fruit companies then employed the dispossessed Latin American natives as low-wage employees.[10]

By the 1930s the United Fruit Company owned 1,400,000 hectares (3.5 million acres) of land in Central America and the Caribbean and was the single largest landowner in Guatemala. Such holdings gave it great power over the governments of small countries, one of the factors confirming the suitability of the phrase "banana republic".[13]

Honduras[]

In the early 20th century, the American businessman Sam Zemurray (founder of the Cuyamel Fruit Company) was instrumental to establishing the "banana republic" stereotype, when he entered the banana-export business by buying overripe bananas from the United Fruit Company to sell in New Orleans. In 1910, Zemurray bought 6,075 hectares (15,000 acres) in the Caribbean coast of Honduras for use by the Cuyamel Fruit Company. In 1911, Zemurray conspired with Manuel Bonilla, an ex-president of Honduras (1904–1907), and the American mercenary Gen. Lee Christmas, to overthrow the civil government of Honduras and install a military government friendly to foreign businessmen.

To that end, the mercenary army of the Cuyamel Fruit Company, led by Gen. Christmas, effected a coup d'état against President Miguel R. Dávila (1907–1911) and installed General Manuel Bonilla (1912–1913). The U.S. ignored the deposition of the elected government of Honduras by a private army, justified by the U.S. State Department's misrepresenting President Dávila as too politically liberal and a poor businessman whose management had indebted Honduras to Great Britain, a geopolitically unacceptable circumstance in light of the Monroe Doctrine. The coup d'état was consequence of the Dávila government's having slighted the Cuyamel Fruit Company by colluding with the rival United Fruit Company to award them a monopoly contract for the Honduran banana, in exchange for the UFC's brokering of U.S. government loans to Honduras.[11][14]

The political instability consequent to the coup d'état stalled the Honduran economy, and the unpayable external debt (c. US$4 billion) of the Republic of Honduras was excluded from access to international investment capital. That financial deficit perpetuated Honduran economic stagnation and perpetuated the image of Honduras as a banana republic.[15] Such a historical, inherited foreign debt functionally undermined the Honduran government, which allowed foreign corporations to manage the country and become sole employers of the Honduran people, because the American fruit companies controlled the economic infrastructure (road, rail, and port, telegraph and telephone) they had built in Honduras.

The U.S. dollar went on to become the legal-tender currency of Honduras; the mercenary Gen. Lee Christmas became commander of the Honduran army, and later was appointed U.S. Consul to the Republic of Honduras.[16] Nonetheless, 23 years later, after much corporate intrigue among the American businessmen, by means of a hostile takeover of agricultural business interests, Sam Zemurray assumed control of the rival United Fruit Company, in 1933.[12]

Guatemala[]

Guatemala suffered the regional socio-economic legacy of a 'banana republic': inequitably distributed agricultural land and natural wealth, uneven economic development, and an economy dependent upon a few export crops—usually bananas, coffee, and sugar cane. The inequitable land distribution was an important cause of national poverty, and the concomitant sociopolitical discontent and insurrection. Almost 90% of the country's farms are too small to yield adequate subsistence harvests to the farmers, while 2% of the country's farms occupy 65% of the arable land, the property of the local oligarchy.[citation needed]

During the 1950s, the United Fruit Company sought to convince the governments of U.S. Presidents Harry Truman (1945–1953) and Dwight Eisenhower (1953–1961) that the popular, elected government of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán of Guatemala was secretly pro-Soviet for having expropriated unused "fruit company lands" to landless peasants. In the Cold War (1945–1991) context of the pro-active anti-communist politics exemplified by U. S. Senator Joseph McCarthy in the years 1947–1957, geo-political concerns about the security of the Western Hemisphere facilitated President Eisenhower's ordering and authorizing Operation Success, the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état by means of which the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency deposed the democratically elected government (1950–1954) of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán and installed the pro-business government of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas (1954–1957), which lasted for three years until his assassination by a presidential guard.[3][17]

A mixed history of elected presidents and puppet-master military juntas were the governments of Guatemala in the course of the 36-year Guatemalan Civil War (1960–1996). However, in 1986, at the 26-year mark, the Guatemalan people promulgated a new political constitution, and elected Vinicio Cerezo (1986–1991) president; then Jorge Serrano Elías (1991–1993).[18]

Modern era[]

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2021) |

Pesticides[]

Dole Food Company and Chiquita Banana International have shifted their focus of maintaining the environments on their plantations and making agriculture more efficient by breeding and growing more resilient versions of foods, such as Cavendish bananas. Both companies have been working to employ better farming practices, especially as regards the use of pesticides. Recently, both companies have received heavy criticism for the amount and effects of the pesticides they have used on their products. Although the pesticides are not harmful to the consumers of the bananas, they can harm the plantation workers. During the 1990s, many workers were exposed to the pesticide Dibromochloropropane (DBCT), which caused side effects of cancer, central nervous system damage, and most commonly, infertility.

Labor conditions and treatment of workers[]

Both Dole Food Company and Chiquita Banana say that in the 21st century their laborers and farmers are being treated much better than they were during the height of the banana republics. It is clear that workers do have better conditions than they did during the 20th century; but these large corporations still suppress labor union movements through intimidation and harassment. Working conditions on banana plantations are dangerous, with very low wages and long hours in difficult conditions. The workers are not cared for and are often replaced as they have very little policy about job security in the case of sickness or injury. The plantation workers are also exposed to toxic pesticides on a daily basis, causing harm. Unionists who pressure these large corporations for better working conditions are commonly targeted and forced to leave their positions. The workers also receive no benefits, and as the plantations are in countries with lax safety regulations, there are minimal health policies.

Modern Honduras and Guatemala[]

Honduras and Guatemala have significant challenges with government corruption as a result of the dictators backed by the United States government, Effraín Ríos Montt (1982–1983) for Guatemala, and Roberto Suazo Córdova (1982–1986) for Honduras. The political instability caused by the dictators falling and being replaced with democratically elected presidents left the government with very little power, leading to corruption of the government and the rise of drug cartels. Today the governments of Guatemala and Honduras still have very little power, as drug cartels control much of the land and are allied with corrupt officials and law enforcement officers. These drug cartels serve as the main transporters of cocaine and other drugs from Latin America to the United States. This has also caused extreme levels of violence, with Honduras having one of the highest homicide rates in the world: 38 per 100,000 people according to UNODC. Guatemala and Honduras also continue to have very low economic diversity, with their primary exports being clothing items and food items. 53% of all exports continue to be sent to the United States.[citation needed]

In art[]

Poetry[]

In the book Canto General (General Song, 1950), the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904–73) denounced foreign corporate political dominance of Latin American countries with the four-stanza poem "La United Fruit Co."; the second-stanza reading in part:[19]

... The Fruit Company, Inc.

Reserved for itself the most succulent,

The central coast of my own land,

The delicate waist of the Americas.It rechristened its territories

As the "Banana Republics",

And over the sleeping dead,

Over the restless heroes

Who brought about the greatness,

The liberty and the flags,

It established a comic opera ...

Novels[]

The novel One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), by Gabriel García Márquez, depicts the imperialist capitalism of foreign fruit companies as voracious socio-economic exploitation of natural resources of the fictional South American town of Macondo and its people. Domestically, the corrupt national government of Macondo abets the business policies and labor practices of the foreign corporations, which brutally oppress the workers.

Modern interpretations[]

Countries that obtained independence from colonial powers in the 20th century have at times thereafter tended to share traits of banana republics due to influence of large private corporations in their politics;[20] for example, Maldives (resort companies),[21] and the Philippines (tobacco industry, U.S. government and corporations).[22][23]

The Kingdom of Hawaii, now the US state of Hawaii, was once an independent country under political pressure from American sugar plantation owners, who in 1887 forced King Kalākaua to write a new constitution that benefited American businessmen at the expense of the working class.[24][25] This constitution is known as the "Bayonet Constitution" due to its threat of force. In the case of Hawaii, the US was also interested in the strategic military significance of the islands, leasing Pearl Harbor[24] and later acquiring Hawaii as a Territory.[26]

On 14 May 1986, then Australian Treasurer Paul Keating stated that Australia might become a banana republic.[27] This has received a lot of commentary and criticism[28][29][30] and is seen as part of a turning point in Australia's political and economic history.[31]

In the 21st century, some critics called the United States a banana republic;[32][33] this is referenced in the title of the book Banana Republicans by Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber.

See also[]

- Absurdistan

- American imperialism

- Banana Wars

- Client state

- Crony capitalism

- Crop diversity

- Dependency theory

- Dictator novel

- Dutch disease

- Failed state

- Dumping (pricing policy)

- Hydraulic empire

- Latin America–United States relations

- McOndo

- Monroe Doctrine

- Narco-state

- Neocolonialism

- Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard (1904)

- Postcolonialism

- Puppet state

- Rentier state

- Rent-seeking

- Resource curse

- Tropico (video game)

- Union of Banana Exporting Countries

- William Walker

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b O. Henry (1904). Cabbages and Kings. New York City: Doubleday, Page & Company. pp. 132, 296.

- ^ Richard Alan White (1984). The Morass. United States Intervention in Central America. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06091145-4. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Big-business Greed Killing the Banana (p. A19)". The Independent. 24 May 2008. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2012 – via The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ Christopher Hitchens (9 October 2008). "America the Banana Republic". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ Malcolm D. MacLean (Summer 1968). "O. Henry in Honduras". American Literary Realism, 1870–1910. 1 (3): 36–46. JSTOR 27747601.

- ^ Chapman, Peter (2009). Jungle capitalists : a story of globalisation, greed and revolution. Edinburgh New York: Canongate. p. 6. ISBN 978-1847676863.

- ^ Big Fruit Archived 2017-03-13 at the Wayback Machine, NY Times

- ^ Where did banana republics get their name? Archived 2017-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist

- ^ Alison Acker (1988). Honduras. The Making of a Banana Republic. Toronto: Between the Lines. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-919946-89-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dan Koeppel (2008). Banana. The Fate of the Fruit that Changed the World. London: Hudson Street Press. pp. 68. ISBN 978-1-59463-038-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alison Acker (1988), p. 63.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peter Chapman (2007). Bananas. How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-84195-881-1. Archived from the original on 2014-07-17. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ Livingstone, Grace (4 April 2013). America's Backyard: The United States and Latin America from the Monroe Doctrine to the War on Terror. Zed Books Ltd. ISBN 9781848136113. Retrieved 22 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Darío A. Euraque (1996). Reinterpreting the Banana Republic. Region and State in Honduras, 1870–1972. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8078-4604-9. Archived from the original on 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ^ W.S. Valentine (November 1916). "Need for Capital in Latin America: Honduras". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. 68: 185–87. doi:10.1177/000271621606800125. JSTOR 1013083. S2CID 220724414.

- ^ George Black (1988). The Good Neighbor: How the United States Wrote the History of Central America and the Caribbean. New York City: Pantheon Books. pp. 35. ISBN 978-0-394-75965-4. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ^ Koeppel, Dan (8 June 2008). "Yes, We Will Have No Bananas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ Carol A. Smith (August 1978). "Beyond Dependency Theory: National and Regional Patterns of Underdevelopment in Guatemala". American Ethnologist. American Ethnological Society. 5 (3): 574–617. doi:10.1525/ae.1978.5.3.02a00090. JSTOR 643758.

- ^ George Black (1988), p. 33.

- ^ Corr, Anders S.; Tacujan, Priscilla A. (July 2013). "Chinese Political and Economic Influence in the Philippines: Implications for Alliances and the South China Sea Dispute". The Journal of Political Risk (Pub by Corr Analytics Inc.). 1 (3). Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Maldives election chaos fuels 'banana republic' fears". Asia One News. 20 October 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ Aquino, Tricia (3 February 2014). "Which public health policy in ASEAN is most susceptible to tobacco industry influence". Interaksyon. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Philippines – Period of American influence". Encyclopædia Britannica. UK. 2014. ISBN 978-1-59339-292-5. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mirza Ph.D, Rocky M. (September 2, 2010). American Invasions: Canada to Afghanistan, 1775 to 2010: Canada to Afghanistan, 1775 to 2010. Trafford Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-4669-5688-9.

- ^ Chambers, John H. (2009). Hawaii. Interlink Books. pp. 184–85. ISBN 978-1-56656-615-5.

- ^ William Adam Russ, The Hawaiian Republic (1894–98): and its struggle to win annexation (Susquehanna U Press, 1992).

- ^ "Banana republic transformed". The Australian. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Barton, Russell; Short, Michael (15 May 1986). "Keating gloom: $ falls". The Age. Fairfax Media.

- ^ Cleary, Paul (17 May 1996). "What will we do when it's all been sold?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media.

- ^ Cleary, Paul (13 June 1998). "If the economy's so good, how come the dollar's so bad?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media.

- ^ Crotty, Martin; Andrew Roberts, David (2009). Turning Points in Australian History (1st ed.). Sydney Australia: UNSW Press. pp. 224–238. ISBN 978-1-921410-56-7.

- ^ Graham, David (10 January 2013). "Is the U.S. on the Verge of Becoming a Banana Republic?". The Atlantic.

- ^ Gabler, Neal (29 November 2017). "America the Banana Republic". billmoyers.com.

External links[]

- From Arbenz to Zelaya: Chiquita in Latin America – video report by Democracy Now!

- Cabbages and Kings – The O. Henry book of short stories wherein he coined the banana republic term

- The Banana Republic: The Myth of the United Fruit Company

- https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/deadly-side-americas-banana-obsession

- https://www.bananalink.org.uk/good-practices-banana-industry/

- https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/food-drink/shopping-guide/bananas

- Pejorative terms

- Political corruption

- Political terminology

- Banana Wars

- United Fruit Company

- O. Henry

- States by power status

- Economic development

- Commodities

- 1900s neologisms

- Bananas in popular culture

- Imperialism studies