Afghan refugees

Parts of this article (those related to 2021 evacuation from Afghanistan) need to be updated. (August 2021) |

Afghan refugees are citizens of Afghanistan who were compelled to abandon their country as a result of major wars, persecution, torture and genocide. The 1978 Saur Revolution followed by the 1979 Soviet invasion marked the first wave of internal displacement and international migration from Afghanistan to neighboring Pakistan and Iran. Smaller numbers went to India[1] or north to reside in various cities across the then Soviet Union. When the Soviet forces left Afghanistan in February 1989, many refugees returned to their homeland. They again migrated to neighboring countries during and after the Afghan Civil War (1992–1996).

Afghanistan became one of the largest refugee-producing countries in the world.[2] Over 6 million Afghan refugees were residing in both Iran and Pakistan in the year 2000.[3] Currently,[when?] they are the third largest group after Venezuelan and Syrian refugees.[4] Some countries that were part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) established special programs to allow thousands of Afghans to resettle in North America or Europe.[5][6][7][8][9] As stateless refugees or asylum seekers, they are protected by the well-established non-refoulement principle and the U.N. Convention Against Torture.

They receive the maximum government benefits and protections in countries such as Australia, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[10][11] For example, those that receive green cards under 8 U.S.C. § 1159 can immediately become "non-citizen nationals of the United States" pursuant to , without needing to meet the requirements of .[12] This allows them to travel with distinct United States passports.[13] Australia provides a similar benefit to admitted refugees.

Internal displacement[]

There are over one million internally displaced people in Afghanistan.[14] Most Afghans experience displacement as a result of military actions and violence by the warring factions, although there are also reasons of major natural disasters.[15] The Soviet invasion caused approximately 2 million Afghans to be internally displaced, mostly from rural areas into urban areas.[15] The Afghan Civil War (1992–1996) caused a new wave of internal displacement, with many citizens moving to northern areas in order to avoid the Taliban totalitarianism.[15] Afghanistan continues to suffer from insecurity and conflict, which has led to an increase in internal displacement.[16][17][18]

Neighboring and regional countries[]

Native people from Afghanistan lawfully reside and work in about 92 countries around the world.[19][20] About three in four Afghans have gone through internal and/or external displacement in their life.[15] Unlike in certain other countries, all admitted refugees and those granted asylum in the United States are statutorily eligible for permanent residency (green card) and then U.S. nationality or U.S. citizenship.[12] All of their children automatically become Americans if they fulfill all of the requirements of , or .[21] This extends their privileges, and gives all of them additional international protection against any unlawful threat or harm.[22]

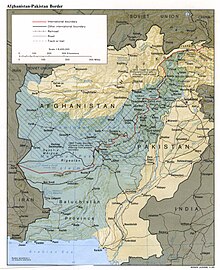

Pakistan[]

Approximately 1,438,432 registered Afghan refugees and asylum seekers temporarily reside in Pakistan under the care and protection of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[19][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] Of these, 58.1% reside and work in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 22.8% in Balochistan, 11.7% in Punjab, 4.6% in Sindh, 2.4% in the capital Islamabad and 0.3% in Azad Kashmir.[25][27] Most were born and raised in Pakistan in the last four decades but are considered citizens of Afghanistan.[30] They are free to return to Afghanistan under a voluntary repatriation program or move to any other country of the world and be firmly resettled there.

Since 2002, around 4.4 million Afghan citizens have been repatriated through the UNHCR from Pakistan to Afghanistan.[25][31] Members of the Taliban and their family reside among the Afghan refugees in Pakistan.[32][33][34][35][36] Others such as the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) applicants and their family members, who are awaiting to be firmly settled in the United States,[5][6][8][9] are also residing in Pakistan. Regarding the Taliban, Prime Minister of Pakistan stated the following:

What the Taliban are doing or are not doing has nothing to do with us. We are neither responsible, nor the spokesperson for the Taliban.[37]

— Imran Khan, July 2021

Iran[]

As of October 2020, there are 780,000 registered Afghan refugees and asylum seekers temporarily residing in Iran under the care and protection of the UNHCR.[19][23][38][39] The majority of them were born in Iran during the last four decades but are still considered citizens of Afghanistan. According to Iranian officials, 2 million citizens of Afghanistan who have no legal documents and over half a million Iranian visa holders also reside in various parts of the country.[38][39] Iran has long been used by Afghans to reach Turkey and then Europe where they apply for political asylum.[40][41][42] As in Pakistan, the Afghan refugees are not firmly settled but reside there on a temporary basis.

Iran's initial response towards Afghan refugees, driven by religious solidarity, was an open door policy where Afghans in Iran had freedom of movement to travel or work in any city in addition to subsidies for propane, gasoline, certain food items and even health coverage.[43][44] In the early 2000s, Iran's Bureau for Aliens and Foreign Immigrants Affairs (BAFIA) initiated registration of all foreigners, including refugees. It began issuing temporary residence cards to certain Afghans.[45] In 2000, the Iranian government also initiated a joint repatriation program with the UNHCR.[45] Laws were passed in order to encourage the repatriation of Afghan refugees, such as limits on employment, areas of residence, and access to services including education.[45]

India[]

India hosts approximately 15,816 Afghan refugees within its borders.[23][46][47] The majority of them reside in the nation's capital Delhi, specifically in the neighborhoods of Lajpat Nagar, Bhogal and Malviya Nagar.[46] Some of them operate "shops, restaurants and pharmacies."[46] Afghan refugees were admitted to India during and after the Soviet–Afghan War (1979-1989).[48] A lot of the once-vibrant Sikhs in Afghanistan and Afghan Hindus have become refugees in India following the wars.[49] Also much of Afghanistan's Christian community thrives within India.[50] In 2021, following the end of the latest war in Afghanistan, India has offered an emergency visa (the 'e-Emergency X-Misc Visa') to some citizens of Afghanistan.[51][52][48]

International aid[]

Due to the ongoing conflict, insecurity, unemployment, and poverty in Afghanistan, the Afghan government had difficulty coping with its internally displaced population in addition to the influx of returnees in a short period of time. In order to meet the needs of returning refugees, the UN has appealed to the international community for $240 million in humanitarian assistance.[14]

In March 2003, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the UNHCR signed a tripartite agreement, as an effort to facilitate voluntary repatriation of Afghan refugees.[53] In 2015, the high level segment of the UNHCR's 66th Executive Committee meeting concentrated on Afghan refugees. This was an effort to bring international attention and promote sustainable solutions for the Afghan refugee situation.[20]

Statistics[]

As shown in the chart below, Afghan refugees were admitted to other countries during the following periods:

- Soviet–Afghan War (1979–1989)

- Afghan Civil War (1992–96)

- Taliban Rule (1996–2001)

- War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)

| Country | Soviet–Afghan War (1979–89) | Civil War (1992–96) | Taliban Rule (1996–2001) | War in Afghanistan (2001–2021) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,100,000 [54] | 1,438,432 | [19][23][25][24][27] | |||

| 3,100,000 [54] | 780,000 | [19][23][38] | |||

| 147,994 | [19] | ||||

| 129,323 | [23] | ||||

| 40,096 | [19][55] | ||||

| 31,546 | [19] | ||||

| 29,927 | [19] | ||||

| 21,456 | [19] | ||||

| 60,000[56] | 15,806 | [23][57] | |||

| 15,490 | [58][59] | ||||

| 14,523 | [19] | ||||

| 12,096 | [19] | ||||

| 10,659 | [19] | ||||

| 9,351 | [19] | ||||

| 7,629 | [23][60][19] | ||||

| 1,161 [61] | 15,336 [61] | 5,573 | [19] | ||

| 5,212 | [19] | ||||

| 4,689 | [19] | ||||

| 4,007 | [19] | ||||

| 3,331 | [19] | ||||

| 2,661 | [23][19] | ||||

| 2,384 | [62] | ||||

| 2,261 | [19] | ||||

| 2,134 | [19] | ||||

Human rights abuses[]

Human rights abuses against admitted Afghan refugees and asylum seekers have been documented widely. This include mistreatment, persecution or torture in Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Greece, Romania, Serbia, Hungary, Germany, the United States and in several other NATO-members states.[63][64][65][66][67][11] Afghans living in Iran, for example, were deliberately restricted from attending public schools.[68][69][70] As the price of citizenship for their family members, Afghan children as young as 14 were recruited to fight in Iraq and Syria for a six-month tour.[71]

Afghan refugees were regularly denied visas to travel between countries to visit their family members, faced long delays (usually a few years)[72] in processing of their visa applications to visit family members for purposes such as weddings, gravely ill family member, burial ceremonies, and university graduation ceremonies; potentially violating rights including free movement, right to family life and the right to an effective remedy.[73][74][75] Racism, low wage jobs including below minimum wage jobs, lower than inflation rate salary increases, were commonly practiced in Europe and elsewhere. Unsanitary conditions have been reported at US air bases,[76][77] and one Afghan refugee's online post of his food portion at Fort Bliss in 2021 drew some hateful responses.[78][79] Many Afghan refugees were not permitted to visit their family members for a decade or two. Studies have shown abnormally high mental health issues and suicide rates among Afghan refugees and their children.[80][81][82][83][84][85]

See also[]

- United States of Al (TV show about Afghan refugee residing with an American family)

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Amstutz, J. Bruce (1994). Afghanistan: The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7881-1111-2. OCLC 948347893.

- ^ "More than seven million refugees displaced in 2012". BBC News. June 19, 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-05.

- ^ "USCR Country Report Afghanistan: Statistics on refugees and other uprooted people". ReliefWeb. June 19, 2001. Retrieved 2021-08-01.

- ^ "Figures at a Glance". UNHCR. June 18, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "US Expands Eligibility for Afghan Refugee Resettlement". Voice of America. August 2, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "US Announces New Refugee Program for Afghans". TOLOnews. August 2, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ "Afghan who aided U.S. arrive at Virginia base, but many others remain in peril". Los Angeles Times. July 30, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Joe Biden approves $300 million for Afghan refugees". Khaama Press. July 24, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "House votes to expand and speed up visa process for Afghans who helped the U.S. during war". CNBC. July 22, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ See generally

- "Matter of Izatula, 20 I&N Dec. 149" (PDF). Board of Immigration Appeals. U.S. Dept. of Justice. February 6, 1990. p. 154.

- "Matter of B, 21 I&N Dec. 66" (PDF). Board of Immigration Appeals. U.S. Dept. of Justice. May 19, 1995. p. 72.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mashiri v. Ashcroft, 383 F.3d 1112". U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Harvard Law School. November 2, 2004. pp. 1115–19. Retrieved 2021-08-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b See generally 8 U.S.C. § 1427; 8 U.S.C. § 1436; 8 U.S.C. § 1452; 8 U.S.C. § 1503;

- "Ricketts v. Attorney General, 897 F.3d 491". U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. July 30, 2018. p. 494 n.3.

While all citizens are nationals, not all nationals are citizens.

- "Ricketts v. Attorney General, 897 F.3d 491". U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. July 30, 2018. p. 494 n.3.

- ^ 22 U.S.C. § 212 ("Persons entitled to passport")

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Return of Afghan Refugees to Afghanistan Surges as Country Copes to Rebuild". www.imf.org. January 26, 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Schmeidl, Susanne (2014). "Sources of Tension in Afghanistan and Pakistan: A Regional Perspective" (PDF). CIDOB Policy Research Project.

- ^ "Afghanistan: 270,000 newly displaced this year, warns UNHCR". UN News. July 13, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "Millions of Afghans Displaced After More Than Four Decades of War". Voice of America. December 14, 2019. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "MIGRATION FLOWS FROM AFGHANISTAN AND PAKISTAN TOWARDS EUROPE: UNDERSTANDING DATA-GAPS AND RECOMMENDATIONS. DESK REVIEW REPORT". International Organization for Migration. August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "How the US and the UK accept far fewer Afghan refugees than other countries". New Statesman. August 19, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "High-Level Segment of the 66th session of the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Programme on the Afghan refugee situation". UNHCR. October 6, 2015. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- ^ See, e.g., generally

- "Fernandez v. Keisler, 502 F.3d 337". U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Harvard Law School. September 26, 2007. pp. 349–50.

- "Gomez-Diaz v. Ashcroft, 324 F.3d 913". U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Harvard Law School. April 7, 2003. p. 915. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

The Child Citizenship Act of 2000, Pub.L. No. 106-395, 114 Stat. 1631, revised the manner in which children of non-citizens born outside the United States are eligible to become U.S. citizens.

- "Belleri v. United States, 712 F.3d 543". U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit. Harvard Law School. March 14, 2013. p. 545. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

A child acquires derivative citizenship by operation of law, not by adjudication.

- "In re Fuentes-Martinez, 21 I&N Dec. 893" (PDF). Board of Immigration Appeals. U.S. Dept. of Justice. April 25, 1997. p. 896 n.4. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

A person who claims to have derived United States citizenship by naturalization of a parent may apply to the Attorney General for a certificate, but a certificate is not required.

- "Robertson-Dewar v. Mukasey, 599 F. Supp. 2d 772". U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas. Harvard Law School. February 25, 2009. p. 779 n.3. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

The Immigration and Nationality Act defines naturalization as 'conferring of nationality of a state upon a person after birth, by any means whatsoever.'

- "Petition for Naturalization of Tubig ex rel. Tubig, 559 F. Supp. 2". U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. Harvard Law School. October 7, 1981. p. 3. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

A person naturalized under § 1433(a) need not meet many of the requirements for naturalization—such as language, residence, and physical presence requirements—imposed upon those who seek naturalization under other provisions.... Thus, qualifying for naturalization under § 1433(a) can be of substantial importance to applicants for naturalization.

- ^ See, e.g., generally 18 U.S.C. § 249; 18 U.S.C. § 876; 18 U.S.C. § 1958; 18 U.S.C. § 2332; 18 U.S.C. § 2441; "United States v. Morin, 80 F.3d 124". U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Harvard Law School. April 5, 1996. p. 126. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Onward Movements of Afghan Refugees (PDF), UNHCR, March–April 2021, retrieved 2021-08-19

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Government delivered first new Proof of Registration smartcards to Afghan refugees". May 25, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Registered Afghan Refugees in Pakistan". UNHCR. December 31, 2020. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ^ "75,000 Afghan refugee families impacted by COVID-19 received emergency cash". ReliefWeb. 29 Jan 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Pakistan: Overview of Afghan Refugee Population". ReliefWeb. February 15, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- ^ "Government delivered first new Proof of Registration smartcards to Afghan refugees". ReliefWeb. February 17, 2020. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

The Proof of Registration (PoR) card is an important protection tool that is issued by Government of Pakistan and provides temporary legal stay and freedom of movement for the 1.4 million registered Afghan refugees in Pakistan.

- ^ "Asylum system in Pakistan". UNHCR. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ^ "PAKISTAN: Tolerance wanes as perceptions of Afghan refugees change". IRIN. February 27, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ^ UNHCR in Pakistan, retrieved 2021-07-29,

Since 2002, in what has become the world's largest assisted return programme, UNHCR has been facilitating voluntary repatriation of millions of Afghan refugees from Pakistan. Ten years after programme began, UNHCR has directly helped around 4.4 million Afghans to return home.

- ^ "Families of Afghan Taliban Live in Pakistan, Interior Minister Says". Voice of America. June 27, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

Pakistan's interior minister said Sunday that the families of Afghanistan's Taliban reside in his country, including in areas around the capital, Islamabad, and the insurgent group's members receive some medical treatment in local hospitals.

- ^ "Nadra cancels ex-senator Hamdullah's citizenship". Pakistan: Dawn News. October 27, 2019. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ "200,000 CNICs fraudulently obtained by Afghans cancelled". Pakistan: Dawn News. January 3, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "Pakistan scraps 200,000 ID cards issued to Afghans". Pajhwok Afghan News. January 3, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ "Pakistan cancels 200,000 fake citizen ID cards held by Afghan refugees". The Hindu. January 3, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ "Most Afghan refugees support Taliban: PM". The Express Tribune. July 29, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Refugees in Iran". UNHCR. October 2020. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

According to the latest figures communicated by the Government in October 2020, on which consultations are ongoing, 800,000 refugees live in Iran, of which 780,000 are Afghans and 20,000 are Iraqis. Additionally, it is estimated that some 2 million undocumented Afghans and nearly 600,000 Afghan-passport holders live in Iran – it is expected that a significant number of those individuals continue to have international protection needs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Refugees and internally displaced persons". The World Factbook. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

refugees (country of origin): 2.1-2.25 million undocumented Afghans, 586,000 Afghan passport holders, 780,000 Afghan refugee card holders, 20,000 Iraqi refugee card holders (2020)

- ^ "Turkey slams US statement on planned resettlement of Afghans". Al Jazeera. August 4, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

- ^ "Afghan refugees are reaching Turkey in greater numbers". The Economist. July 31, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-01.

- ^ "Turkey accelerates security wall construction along Iranian border amid migrants' flow". Arab News. July 29, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ^ Farzin, Farshid (2013). "Freedom of movement of Afghan refugees in Iran". Forced Migration Review. 1: 44: 85–86 – via Advanced Placement Source.

- ^ Koepke, Bruce 2011. The situation of Afghans in the Islamic Republic of Iran nine years after the overthrow of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Middle East Institute.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Second-generation Afghans in Iran: Integration, Identity and Return" (PDF). Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. April 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Aafaq, Zafar (17 August 2021). "'Our future unknown': Afghan nationals in India wary of Taliban". Al Jazeera.

- ^ Lalwani, Vijayta (18 July 2021). "As tensions rise in Afghanistan, refugees in Delhi worry about their relatives back home". Scroll.in.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alam, Majid (18 August 2021). "As India Mulls Giving Asylum to Afghan Nationals, A Look at Its Refugee Policy And Citizenship Rules". News18. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/more-afghan-sikhs-hindus-migrating-to-india-from-afghanistan/30778319.html

- ^ Iyengar, Radhika (28 July 2018). "The Afghan Christian refugees of Delhi". Mint. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ "India says it will prioritize Hindus and Sikhs in issuing 'emergency visas' to Afghans". The New York Times. 2021-08-25. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "India announces emergency e-visa for Afghans". The Hindu. 17 August 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan tripartite agreement with Pakistan". UNHCR. March 18, 2003. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 1999

- ^ AUSTRIA, STATISTIK. "Bevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit und Geburtsland". Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Religion/Islamophobia-AntiMuslim/Civil%20Society%20or%20Individuals/RitumbraM1.pdf

- ^ "Afghan refugees in India cast adrift amid coronavirus pandemic". DW News. May 10, 2020. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "Country of origin: Afghanistan". Great Falls Tribune. December 21, 2019. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- ^ "Where does the world stand on Afghan refugees?". Al Jazeera. August 19, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

As of July 31, 2021, the US had only admitted 494 Afghan refugees for the fiscal year 2021, which ends September 30. A year earlier, 604 were resettled.

- ^ "Indonesia fact sheet" (PDF), UNHCR, December 2020, retrieved 2021-07-31

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erlich 2006

- ^ "Romania: Refugee and migrant figures for 2020". March 30, 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ^ "Afghans Who Fled the First Taliban Regime Found Precarious Sanctuary in Pakistan. New Refugees May Get an Even Colder Welcome". Time. August 18, 2021. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

Those who fled the Taliban's first reign grapple with the constant threat of deportation, police harassment, and discrimination.

- ^ "For Afghan Refugees, Pakistan Is a Nightmare—but Also Home". Foreign Policy. May 9, 2019. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- ^ "Will the UN become complicit in Pakistan's illegal return of Afghan refugees?". The New Humanitarian. November 10, 2016. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- ^ "'Harassment' drives Afghan refugees from Pakistan". BBC News. February 26, 2015. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- ^ "Afghan Migrants Could Face 'Shocking' Punishments In Iran Under Draft Law". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. December 1, 2020. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- ^ "Unwelcome Guests Iran's Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights". Human Rights Watch (20 November 2013). 20 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Bezhan, Frud (2 September 2017). "Class Act: Iranians Campaign To Allow Afghan Refugee Kids Into School". Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ "The price of an education for Afghan refugees in Iran". The Guardian. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Homsi, Nada (1 October 2017). "Afghan Teenagers Recruited in Iran to Fight in Syria, Group Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Rosenblatt, Kalhan (4 September 2017). "Combat Translators Saved Their Lives. Now These Veterans Are Fighting to Bring Them to the US". NBC News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Chokshi, Niraj (13 July 2017). "After Visa Denials, Afghan Girls Can Attend Robotics Contest in US". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Carolan, Mary (26 January 2018). "Visa delays of more than a year may breach European directive" (January 26, 2018). The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ "The refugees who gave up on Britain" (1 June 2018 06.00 BST). The Guardian. 1 June 2018. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Jordan Williams (August 24, 2021). "Afghan refugees living in 'dire conditions' at US air base: report". The Hill. Archived from the original on September 2021 – via Microsoft News.

- ^ Lubold, Vivian Salama, Jessica Donati and Gordon (2021-08-24). "Afghan Refugees Endure Unsanitary Conditions After Harrowing Escapes". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ^ "难民抱怨美军基地伙食"寒酸" 美国网民:滚回阿富汗". Guancha. September 6, 2021. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021.

- ^ "Afghan Refugee's Photo of Food Served at US Camp Met With Vicious Online Hate". News18. 2021-09-06.

- ^ RIM MGHIR; WENDY FREED; ALLEN RASKIN; WAYNE KATON, RIM MGHIR; WENDY FREED; ALLEN RASKIN; WAYNE KATON (1 January 1995). "Depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among a community sample of adolescent and young adult Afghan refugees". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 183 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1097/00005053-199501000-00005. PMID 7807065. S2CID 27962373.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Nejad, RM; Klöhn-Saghatolislam, F; Hasan, A; Pogarell, O (May 2017). "[Mental disorders and problems in afghan refugees: The clinical perspective]". MMW Fortschritte der Medizin. 159 (9): 64–66. doi:10.1007/s15006-017-9653-y. PMID 28509013. S2CID 195341301.

- ^ Mghir, Rim, Raskin, Allen, Mghir, Rim, Raskin, Allen (1999). "The Psychological Effects of the War in Afghanistan On Young Afghan Refugees From Different Ethnic Backgrounds". International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 45 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1177/002076409904500104. PMID 10443247. S2CID 22780561.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Slewa-Younan, Shameran; Yaser, Anisa; Guajardo, Maria Gabriela Uribe; Mannan, Haider; Smith, Caroline A.; Mond, Jonathan M. (24 August 2017). "The mental health and help-seeking behaviour of resettled Afghan refugees in Australia". International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 11 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/s13033-017-0157-z. PMC 5571658. PMID 28855961.

- ^ Yaser, Anisa; Slewa-Younan, Shameran; Smith, Caroline A.; Olson, Rebecca E.; Guajardo, Maria Gabriela Uribe; Mond, Jonathan (12 April 2016). "Beliefs and knowledge about post-traumatic stress disorder amongst resettled Afghan refugees in Australia". International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 10 (1): 31. doi:10.1186/s13033-016-0065-7. ISSN 1752-4458. PMC 4828823. PMID 27073412.

- ^ Stempel, Carl; Sami, Nilofar; Koga, Patrick Marius; Alemi, Qais; Smith, Valerie; Shirazi, Aida (28 December 2016). "Gendered Sources of Distress and Resilience among Afghan Refugees in Northern California: A Cross-Sectional Study". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 14 (1): 25. doi:10.3390/ijerph14010025. PMC 5295276. PMID 28036054.

Sources[]

- "Tough times follow Afghan refugees fleeing Taliban to Delhi". The Indian Express. July 24, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex - Australia". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- Bose, Nayana (March 10, 2006). "Afghan refugees in India become Indian, at last". UNHCR. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- Carberry, Sean (May 7, 2013). "Afghan-Pakistani Forces Exchange Fire Along Shared Border". NPR. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Erlich, Aaron (July 2006). "Tajikistan: From Refugee Sender to Labor Exporter". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- Haug, Dr. habil. Sonja; Müssig, Stephanie M.A. & Dr. Anja Stichs (2009). Bundesamt für Flüchtlinge und Migration : Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland (in German) (2009 ed.).

- Iqbal, Mohamed (July 7, 2012). "Kabul looks to Qatar support at aid meet". The Peninsula. Archived from the original on August 24, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- Jones, Sophie (July 2010). "Afghans in the UK" (PDF). Information Centre about Asylum and Refugees. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- "Afghan Migration after the Soviet Invasion" (PDF). National Geographic Society. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Nordland, Rod (November 20, 2013). "Afghan Migrants in Iran Face Painful Contradictions but Keep Coming". The New York Times. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- Shahbandari, Shafaat (November 30, 2012). "Afghans take hope from UAE's achievements". Gulf News. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- Stainburn, Samantha (May 22, 2013). "UK, Denmark to give Afghan interpreters visas". GlobalPost. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "Immigrant population by place of birth and period of immigration (2006 Census)". Statistics Canada. 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- "UNHCR Global Report 2005: Turkey" (PDF). UNHCR. 2005. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- "2013 UNHCR country operations profile - Islamic Republic of Iran". UNHCR. 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- "Afghanistan 10 years after Soviet pull-out". UNHCR. February 12, 1999. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "2013 UNHCR country operations profile - Pakistan". UNHCR. 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. 2013. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

External links[]

- Colombia to Host Afghans Making Their Way to the United States (U.S. News & World Report, Aug. 20, 2021)

- Afghanistan: Pakistan fences off from Afghan refugees (BBC News, Aug. 18, 2021)

- After 20 years of destruction, the US has a moral obligation to let in 1 million Afghan refugees (Business Insider, Aug. 16, 2021)

- Pakistan considers 'Iran model' to tackle Afghan refugee spillover (TRT World, July 20, 2021)

- Senate agrees to spend $2.1 billion on Capitol security and Afghan refugee aid (Washington Examiner, April 29, 2021)

- Afghan refugees

- Afghan diaspora

- Refugees by war