Airboat

An airboat (also known as a planeboat, swamp boat, bayou boat, or fanboat) is a flat-bottomed watercraft propelled by an aircraft-type propeller and powered by either an aircraft or automotive engine.[a] They are commonly used for fishing, bowfishing, hunting, and ecotourism.

Airboats are a common means of transportation in marshy and/or shallow areas where a standard inboard or outboard engine with a submerged propeller would be impractical, most notably in the Florida Everglades but also in the Kissimmee and St. Johns rivers, and the Mekong River and Delta, as well as the Louisiana bayous and Mesopotamian Marshes.

Overview[]

The characteristic flat-bottomed design of the airboat, in conjunction with the fact that there are no operating parts below the waterline, allows for easy navigation through shallow swamps and marshes; in canals, rivers, and lakes; and on ice and frozen lakes. This design also makes it ideal for flood and ice rescue operations.[1][2]

The airboat is pushed forward by the propeller, which produces a rearward column of air behind it. The resulting prop wash averages 150 miles per hour (241 km/h). Steering is accomplished by diverting that column of air left or right as it passes across the rudders, which the pilot controls via a "stick" located on the operator's left side. Overall steering and control is a function of water current, wind, water depth, and propeller thrust. Airboats are very fast compared to comparably-sized motorboats: commercial airboats generally sail at speeds of around 35 miles per hour (30 kn) and modified airboats can go as fast as 135 miles per hour (117 kn).[3]

Stopping and reversing direction are dependent upon high operator skill, since airboats, like most boats, do not have brakes.[3] They are incapable of traveling in reverse, unless equipped with a reversible propeller. Some designs use a clam shell reversing device intended for braking or backing up very short distances but these systems are not commonly used.[citation needed]

The operator and passengers, are typically seated in elevated seats that allow visibility over swamp vegetation. High visibility lets the operator and passengers see floating objects, stumps and other submerged obstacles, and animals in the boat's path.[1][4]

In the United States, a typical good-quality airboat in 2004 would have cost between $33,000[5][b] and $70,000.[6] In a developing country like Iraq, however, an airboat could be purchased[when?] for as little as 2.5 million Iraqi dinars, or $2,147.[7] In spite of their high cost, airboats are very widely used by civilians and tour operators: there are 12,164 airboats, 1,025 of them commercial, in Florida alone as of December 2017.[3] Airboats are widely used in other Gulf Coast states, especially Louisiana, but they can be found in rivers, marshes, and icy areas around the world, from Nebraska[8] to Siberia.

Soviet airboats and aerosleds[]

Airboats and airboat-like craft have been used in the Soviet Union and its successor states since the Second World War and possibly earlier. Some true airboats—vessels that operated entirely in the water—were used by the Soviet military in World War II. These true airboats include the , a 1,200-kilogram (2,600 lb) WWII armed boat reportedly capable of speeds up to 60 kilometres per hour (37 mph; 32 kn).[9] However, most Soviet airboats are aerosleds (referred to as "aerosanis" in Russian). An aerosled is an aircraft propeller driven amphibious vehicle best described as a hybrid of a sled, airboat, and ground effect vehicle. Thousands of aerosleds were used as cargo and passenger vehicles in Siberia, where they excelled because they could cope equally well with the icy Siberian winter and the muddy, marshy conditions of Rasputitsa season (similar to the American mud season), when raw or thawing snow makes travel by road impossible. Aerosleds are still in use today.[10] The Tupolev A-3 Aerosledge is a quintessential example of this type of vehicle; it can reach speeds of up to 120 kilometers per hour (74.6 mph) on snow and 65 km/h (40.4 mph) on water.[11]

History[]

The first airboat was invented in 1905 in Nova Scotia, Canada by Alexander Graham Bell.[12][13] The earliest airboats to see any kind of use date to 1915, when airboats by the British Army in the World War I Mesopotamian Campaign.[14] However, airboats were not widely used by civilians until the 1930s.[12]

First prototypes[]

The earliest ancestors of the airboat were waterborne vehicles for testing aircraft engines. The first airboat was the Ugly Duckling, an aircraft propeller testing vehicle built in 1905 in Nova Scotia, Canada by a team led by Dr. Alexander Graham Bell. Ugly Duckling was a catamaran-type boat propelled by an "aerial propeller" hooked up to a water-cooled aircraft engine weighing 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg). The makeshift raft-like vessel was unable to obtain a speed faster than 4 miles per hour (3.5 knots), though the "rapid rotation of the propeller" led Dr. Bell to believe that the vessel could have had a theoretical top speed of "thirty or forty miles an hour," comparable to some modern airboats, if drag was completely eliminated.[15] Brazilian aviation pioneer Santos Dumont built a similar catamaran vessel for testing an aircraft engine in 1907, which he termed a hydrofoil.[16]

The , French aviation pioneers, made major steps towards modern airboats with their 1907 speedboat La Rapière II (Rapier II). La Rapière II was an 8-metre (26 ft) long mahogany speedboat powered by a partially above water aircraft propeller hooked up to a 20 hp 4 cylinder Panhard-Levassor engine. The boat was steered by a conventional rudder in the water, which was hooked up to a ship's wheel.[17] La Rapière II could achieve speeds of up to 26 kilometres per hour (16 mph; 14 kn) with two people on board and 25 kilometres per hour (16 mph; 13 kn) with 3-4 people on board.[16] In France Jacques Schneider, of Schneider Trophy fame, developed and experimented with his own multi-passenger brand of airboat circa 1913–1914.[18]

Early airboats[]

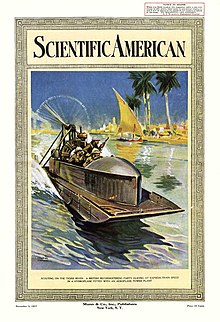

The first airboats to see any real use date to 1915. The British Army used airboats, which they referred to as Lambert "Hydro-Glisseurs",[c] in the Mesopotamian Campaign of the First World War. These "Hydro-Glisseurs" were small, flat-bottomed hydroplanes with metal-clad wooden hulls propelled by a large aircraft fan that allowed them to reach speeds of up to 55 miles per hour (48 kn).[19] They were primarily used for reconnaissance on the Tigris River.[14] The first of these airboats, HG 1 Ariel, was constructed using the engine and propeller of a wrecked Royal Australian Air Force Farman MF.7 biplane and was provided to the forces in Mesopotamia by the British Raj.[20] Following Ariel's successful deployment in the campaign upriver to Kut in 1915–1916, Britain ordered seven purpose-built airboats from Charles de Lambert's eponymous company De Lambert. Eight of these vessels were in operation in 1917, increasing to nine by the 1918 Armistice.[21] A dedicated repair slipway for these boats was built at the Motor Repair Dockyard in Baghdad, indicating both their importance to the British war effort and the difficulty of maintaining them.[21]: 67-8

Following the war, Lambert airboats were used as ferries on the shallow waters of the upper Yangtze River, on the Huangpu River, and elsewhere. Like their military counterparts, these airboats were manufactured in France, though they were assembled in Shanghai. They had drafts of only seven inches and could cruise at up to 32 miles per hour (28 kn). Lambert airboats were also used widely on the upper Missouri River and on the marshes of the Florida Everglades.[19]

Farman Aircraft, the company that built the engines for the WWI military airboats, began producing civilian airboats in the 1920s. It marketed airboats for use as water taxis and as light cargo vessels or patrol boats for French colonial governments. Its airboats sold for 25,000 to 50,000 francs depending on the model, a price that proved too steep for potential buyers; the company pulled out of the boat business by the end of the 1920s.[16]

These early European airboats were significantly different from their modern counterparts. Compared to the airboats of today, early European airboats tended to be somewhat larger, had higher freeboards, and lacked a protective cage surrounding the propeller.[22] They also had a different steering mechanism: early airboats were steered with a rudder in the water controlled by a steering wheel with throttle control provided by a gas pedal, like an automobile.[21] More modern airboats use an air rudder controlled with a joystick for steering.

Early American airboats[]

Glenn Curtiss is credited with building a type of airboat in 1920 to help facilitate his hobby of bow and arrow hunting in the Florida backwoods. The millionaire, who later went on to develop the cities of Hialeah and Miami, combined his talents in the fields of aviation and design to facilitate his hobby, and the end result was Scooter, a 6-passenger, closed-cabin, propeller-driven boat powered by an aircraft engine that allowed it to slip through wetlands at 50 miles per hour (43 kn).[23][24]

Airboats began to become popular in the United States in the 1930s, when they were independently invented and used by a number of Floridians, most living in or around the Everglades.[12] Some Floridians who invented their own airboats include frog hunter Johnny Lamb, who built a 75-horsepower airboat in 1933 he called the "whooshmobile" and Chokoloskee Gladesmen Ernest and Willard Yates, who built an airboat in 1935 they steered via reins attached to a crude wooden rudder.[12][13] Yates holds the ignominious honor of being the first person to die in an airboating accident, when the engine dislodged and sent the spinning propeller into him.[3][13]

An improved airboat was invented in Utah in 1943 by Cecil Williams, Leo Young, and G. Hortin Jensen.[25] Their boat, developed and used near Brigham City, Utah, is sometimes erroneously called the first airboat. At the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge in northern Utah, Cecil S. Williams and G. Hortin Jensen sought a solution to the problem of conducting avian botulism studies in the shallow, marshy hinterlands. By installing a 40-horsepower Continental aircraft engine, purchased for $99.50, on a flat-bottomed 12-foot long aluminum boat, they built one of the first modern airboats. Their airboat had no seat, so the skipper was forced to kneel in the boat. They dubbed it the Alligator I as a response to a joking comment from US Fish and Wildlife Service headquarters that they should "get an alligator from Louisiana, saddle up and ride the critter during their botulism studies."[26] Their airboat was the first to use an air rudder (a rudder directing the propeller exhaust rather than the water), a major improvement in modern airboat design.[27]

The purpose of Williams, Young, and Jensen's airboat was to help preserve and protect bird populations and animal life at the world's largest migratory game bird refuge.[28] The Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge near Brigham City, Utah is a wetlands oasis amid the Great Basin Desert and an essential stopping point for birds migrating across North America. The need for a practical way to navigate a challenging environment of wetlands, shallow water, and thick mud helped inspire Williams, Young, and Jensen to create the flat-bottom airboat, which they initially called an "air thrust boat."[27] Designs and subsequent improvements and practical use of the air thrust boats appears to have been a collaborative effort. LeeRue Allen, who worked at the Refuge since 1936 appears to have also been involved and helped to document a history of the events.[29]

Many of the early airboats built at the refuge in Utah were shipped to Florida. Early records show it cost roughly $1,600 to build a boat, including the engine.[27]

Over the years, the standard design evolved through trial-and-error: an open, flat bottom boat with an engine mounted on the back, the driver sitting in an elevated position, and a cage to protect the propeller from objects flying into them.

Manufacture and design[]

Airboat manufacturers tend to be small, family run businesses that assemble built-to-order boats. Most airboats are manufactured in the United States, although they are also built in Russia,[11] Italy,[30] Finland,[2][31] Japan,[32] Australia,[4] and elsewhere. Prior to 1950, most airboats were manufactured in France by companies and individuals such as Farman, De Lambert, and René Couzinet.[16][failed verification]

Modern, commercially manufactured airboat hulls are made of aluminum or fiberglass. The choice of material is determined by the type of terrain in which the vessel will be operated; airboats intended for use in icy conditions will have sturdier polymer coated aluminum hulls while airboats intended for use in marshes will have lighter fiberglass hulls, for instance.[5] Standard hunt/trail boats are 10 feet (3.0 m) long with a two- to three-passenger capacity. Tour boats can be much larger, accommodating 18 passengers or more.[3]

Engines are either an air-cooled, 4- or 6-cylinder aircraft or water-cooled, large-displacement, V8 automotive engine, ranging from 50 to over 600 hp. Automotive engines tend to be less expensive due to readily-available replacement parts and less expensive high octane automotive gas. Since an opposed, 4- or 6-cylinder (O4 or O6) aircraft powerplant contains fewer moving parts than a standard automotive engine, it is easier to repair and weighs less.[3][1] However, automotive engines can be repaired by more-common car mechanics and do not require specialized repair personnel like aircraft engines do.[5]

Most of the sound produced by an airboat comes from the propeller, although the engine itself also contributes some noise. Modern airboat designs are significantly quieter thanks to mufflers and multi-blade carbon-fiber propellers.[citation needed]

Safety[]

As with any vehicle, the safety of an airboat is dependent on the training and skill of its operator and the use of safety features like seat belts and flotation devices/life jackets. Airboats should only be piloted by trained and qualified operators,[5] and knowledge of operational safety is essential when operating an airboat.[3]

Over 75 airboat accidents happened in Florida between 2014 and 2017, resulting in seven deaths and 102 severe injuries. Most (five of seven) deaths were drownings, and 90 percent of accident victims were not wearing life jackets, even though only 30 percent knew how to swim. Not wearing a seat belt is another major predictor of injury in an accident: 40 percent of injured victims and the only two non-drowning fatalities were flung from their seats in the crashes. The most common injuries suffered in airboat accidents are severe cuts, bruises, and broken limbs. Other severe injuries are not uncommon: 10 percent of injured people suffered neck and back injuries requiring surgery and long-term pain medication and another 10 percent suffered traumatic head and brain injuries.[3]

Most airboat accidents—64%—are the fault of the operator, according to a 2017 analysis by the Miami New Times, almost always due to one of three factors:[3]

- a lack of boating education or training;

- a lack of safety equipment, such as seat belts or flotation devices, or a failure to properly use safety equipment;

- or reckless behavior, including drug or alcohol consumption and improper lookout.

The engine and propeller of an airboat are enclosed in a protective metal cage that prevents objects, such as tree limbs, branches, clothing, beverage containers, passengers, or wildlife, from coming into contact with the whirling propeller, which can cause traumatic injury to the operator and passengers or devastating damage to the vessel.[5] Safety cages do not always work perfectly, however: people have had their fingers sliced off by airboat propellers, and tree branches entering safety cages have wrecked airboat propellers and sprayed the operators and passengers with woodchips and other shrapnel.[3]

Airboats are prone to capsizing and sinking because they are top-heavy, unstable, and extremely shallow draft. This makes them especially dangerous on the open sea or in rough or stormy conditions.[33] Airboats with a "long-belt gear reduction drive unit" and an automobile engine avoid these risks because the long belt allows for the engine to be mounted inside the hull, which lowers the center of gravity and lowers the capsizing risk.[5] Some companies and organizations, including Airboat West and the Los Alamos National Laboratory, have built airboats with low centers of gravity for use in windy or rough conditions or in rescues with obstacles like low-hanging power lines.[34] Airboats can also be equipped with autoinflation devices, similar to car airbags or autoinflating personal life vests, that can reduce the risk of capsizing.[5]

In 1999 the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service's , located in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, produced a 70-minute training video entitled Airboat Safety – Design-Operation-Maintenance in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Jacksonville, Florida. The video includes an early history of airboats and interviews with two airboat manufacturers in Florida. It was considered to be the only airboat video of its kind when it was made and may still be the only one with the range of airboat subject matter ever produced in the US. Since it was produced by the federal government of the United States, it is in the public domain. Five hundred copies of the video were produced.[35]

Regulation[]

On March 30, 2018 Gov. Rick Scott of Florida signed “Ellie’s Law,” which requires operators to complete CPR instruction and a course on airboats run by the state's wildlife commission. The law is named after Elizabeth “Ellie” Goldenberg, who died from an airboat accident in Miami-Dade County the day after her graduation from college.[36] Beginning July 1, 2019, airboat operators will need to be able to show proof they completed the training courses. Violations are a misdemeanor offense punishable by up to a $500 fine.

Florida state law also stipulates that airboats must have an "automotive-style factory muffler, underwater exhaust, or other manufactured device capable of adequately muffling the sound of the engine exhaust" and an international orange flag that is at least 10" by 12" flying from a mast or flagpole that is at least 10 feet taller than the lowest point on the boat, in order to increase visibility and reduce the odds of a collision.[37]

Airboat operators, pilots, or drivers in Florida must be 14 or older.[38]

Rescue[]

In recent years, airboats have proven indispensable for flood, shallow water, and ice rescue operations. As a result, they have grown in popularity for public safety uses.

During the flooding of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, August 29, 2005, airboats from across the United States rescued thousands of flood victims.[39] Thirty airboats crewed by civilian volunteers evacuated over 1,100 patients and 4,000 medical personnel and family members from four downtown New Orleans hospitals in less than 36 hours.[40] This "Cajun Navy" morphed into a grassroots volunteer search and rescue organization that has deployed to rescue people during Hurricane Harvey,[41] Hurricane Florence,[42] and other natural disasters.[43][44]

Numerous articles have been published in fire-rescue trade journals such as Fire Engineering and describing the advantages, capabilities, and benefits of using airboats for water rescue operations, and providing in-depth description of actual water rescue incidents, including the flooding of New Orleans.[1][40][45][5][46][47]

Airboats are particularly effective at water rescues in shallow, marshy, or icy winter environments. Airboats are partially amphibious and can therefore navigate effectively over obstacles, such as partially submerged buildings and wreckage or sea ice, that would stop a normal boat. In ice rescues, use of airboats cuts the average rescue time from 45 to 60 minutes to seven to 12 minutes, according to data from Minnesota fire departments. They are also faster, larger, safer, and more durable than other small boats used in ice rescues.[5]

Though airboats are highly effective at water and ice rescues, airboats and helicopters do not work well together. Rotor wash from low-flying helicopters can push and even capsize airboats. During post-Katrina rescue operations, a helicopter's rotor wash was reported to have capsized one airboat, and many airboats were blown into the sides of buildings, standing utility poles, and bridge pilings by low-flying helicopters.[40]

Military use[]

Airboats are used by various militaries and border patrols around the world as well as by the U.S. Coast Guard.[48] In addition to the use of airboats by the British Army in the Mesopotamian Campaign of WWI and by the Soviet Union in the Eastern Front of WWII, airboats have been used by the US Army and Iraqi security forces in the Vietnam and Iraq wars, respectively.

During the Vietnam War the Hurricane Aircat airboat was used by U.S. Special Forces and South Vietnamese troops to patrol riverine and marshy areas where larger boats could not go.[49] Two of these airboats were also used by the Khmer National Navy after they were captured from the U.S. Special Forces by the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in September 1967.[50][51]

Airboats are also used in Texas and Iraq for border patrol.[52] The airboats used in Iraq were supplied by American companies and assembled in Iraq by American civilian contractors, and they are used by both American and Iraqi forces to patrol the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the marshes of southeastern Iraq, and the Shatt al-Arab waterway, the latter two of which include parts of the Iran-Iraq border.[53] Modern Iraqi military airboats are 18 feet (5.5 m) long, powered by 454 hp engines hooked up to 78-inch (2.0 m) Whirlwind propellers, and armed with M240 crew-served machine guns.[53] The Nov/Dec 2007 issue of had an article on airboats used in Vietnam and in Iraq and has had numerous articles on airboats used by U.S Coast Guard and other state and county EMS units for rescue of ice fisherman and rescue in floods or after hurricanes.

In 2013 the Iraqi Ministry of Oil purchased 20 airboats for use as personnel transport, patrol, and cable laying and light cargo boats in the rivers and marshes of Iraq.[7]

See also[]

- Hovercraft

- Hydrocopter

- Rotor ship, a similar type of vessel using a vertical "pipe" to propel the air

Notes[]

- ^ In early aviation history the term airboat was applied to seaplanes or flying boats, i.e.amphibian aircraft capable of taking off and landing on water surfaces. Early airboats were known as "hydroglisseurs" (airboat in French, lit. "water slider"), hydroplanes, hydrofoils, or other names. See e.g. Flying Volume 4 (1915-1916) and Cercle du Mononautisme Classique Archives historiques Archived 2016-03-13 at the Wayback Machine (in French).

- ^ The source cited states the price of an airboat as $25,000 to $40,000 in 2004, which is equal to between $33,000 and $53,000 in 2018 dollars.

- ^ Lambert refers to their manufacturer, the De Lambert company of France, and "Hydro-Glisseur" means "airboat" in French.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Dummett, Robert (January 1, 2006). "Rescue on The Chattahoochee". Fire Engineering. Vol. 159 no. 1. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New Ideas in Boat Design". Helsinki, Finland: Arctic Airboat. 2015. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Vi Gomes, Isabella (December 12, 2017). "Florida Airboat Accidents Have Killed Seven and Injured Dozens in Recent Years". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Airboats International -- About Us". Carrington, NSW, Australia: Airboats International. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Dummett, Robert (March 1, 2004). "The Use of Airboats in Ice and Water Rescue Emergencies". Fire Engineering. Vol. 157 no. 3. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ "Pre-Owned Airboats". American Airboat Corp. Archived from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "تجهيز زوارق هوائة نهرية" (PDF) (Press release) (in Arabic). Baghdad: جمهوريى العراق وزارة النفط شركة الاستكشاف النفطية. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2018-07-10 – via Iraq Business News.

- ^ Mensik, Dan, ed. (October 2017). "Uniting to Preserve Our River Rights" (PDF). RiverTalk. Fremont, NE: Nebraska Airboaters Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ "WWII navy information and facts". War is Over. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Hanlon, Mike (November 6, 2006). "The remarkable part boat, part sled, part ground-effect Tupelov aerosled". New Atlas. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McLeavy, Roy, (1982). "Jane's Surface Skimmers", pp 65–67, London, England: Jane's Publishing Company Limited. ISBN 0-86720-614-4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kirk, Dennis (17 February 2011). "Airboats simplify swampland surveillance". Charlotte County Florida Weekly. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Anderson, Lars (October 21, 2010). "Lars Anderson: Talking Airboats: Can You Hear Me Now?". The Gainesville Sun. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Delano, Anthony (2016-09-23). Guy Gaunt: The Boy From Ballarat Who Talked America Into the Great War. Australian Scholarly Publishing. p. 184. ISBN 9781925333206.

- ^ Bell, Alexander Graham; Adler, Cyrus (1907). Aërial Locomotion: With a Few Notes of Progress in the Construction of an Aërodrome. Press of Judd & Detweiler, Incorporated. pp. 21–26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Archives historiques". Cercle du Mononautisme Classique (in French). Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ Les hydravions d'Alphonse Tellier (PDF) (Report) (in French). hydroretro.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ History of Aviation c.1972 by Kenneth Munson and J. R. Taylor

- ^ Jump up to: a b ""Hydro-Gliders" the latest thing in Chinese transportation, expected to open the upper Yangtze to rapid navigation". Far Eastern Fortnightly. New York: The Far Eastern Bureau. 8 (1): 6. January 3, 1921.

- ^ "Reminiscence of the Essen Raids". Flying. Vol. 4 no. 1. New York City: Flying Association at the office of the Aero Club of America. January 1916.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hall, Leonard Joseph; Hughes, Robert Herbert Wilfrid (1921). The Inland water transport in Mesopotamia. London Constable. Archived from the original on 2015-12-17. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ Farman, Avion (1922). "Hydroglisseurs Farman" (Press release) (in French). Boulogne Billancourt, France: Farman Aviation Works. Archived from the original on 2018-07-09. Retrieved 2018-07-09 – via Gallica.

- ^ Curtiss, Richard. "The 1920 Curtiss "Scooter" airboat". CurtissWay. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ McIver, Stuart B. (1998). "Chapter 28: Who Invented the Airboat?". Dreamers, Schemers and Scalawags. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 205. ISBN 9781561641550.

- ^ World's First Airboat https://scontent-sjc2-1.xx.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/15109419_1779337522340086_2556976957131532493_n.jpg?oh=dbe23a6b7eb63dce33d92050b0c8f303&oe=59886030[dead link]

- ^ "Tuesday Trivia: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Airboat". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service History -- Facebook. U.S. Department of the Interior. November 15, 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Grass, Ray (May 8, 2007). "World's first airboat hatched at Bear River refuge in '40s". Deseret News. Deseret Morning News. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, Grassland Unit Restoration Project - Phase I". Ducks Unlimited. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Allen, Lee Rue. "Oral History Program" (1972). History. Ogden, Utah: Weber State University.

- ^ Pearce, William (2016-01-24). "Idroscivolanti and the Raid Pavia-Venezia". Old Machine Press. Archived from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ Torsti tietää, Helsingin Sanomat, 28.3.2010 s. D 7

- ^ Ko. "エアボートを、レジャー用として、救助用として、広く日本で普及させたい". Airboats.jp (in Japanese). Tokyo: Fresh Air Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Enfield, Samuel; Burr, R.; Badgett, R.; et al., eds. (April 15, 1966). Airboats (PDF) (Technical report). San Francisco: Army Concept Team in Vietnam. R-1590.0 – via DTIC.

- ^ Butterman, Eric (August 2013). "A boat that walks on water". ASME. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Archived from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ Cooper, Ken (1999). Airboat safety design, operation, maintenance (Videodisk). Shepherdstown, WV: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Event occurs at 70 minutes. OCLC 79818231. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ Swisher, Skyler. "Gov. Scott signs 'Ellie's Law' creating new safety rules for Everglades airboat operators". Sun-Sentinel.com. Archived from the original on 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ Florida Atlantic University Diving and Boating Safety Committee (February 2014). Diving and Boating Safety Manual (PDF). Boca Raton: Florida Atlantic University Environmental Health and Safety. pp. 91–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "The 2010 Florida Statutes (including Special Session A)". Chapter 327.39, Statute No. Title XXIV of 2014. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ Mercedes, Cheryl (August 24, 2015). "LIFE BEYOND KATRINA: Cajun couple rescues hundreds from flooded homes". WAFB. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dummett, Robert (May 1, 2006). "The Evacuation of New Orleans After The Levees Broke". Fire Engineering. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ "The "Cajun Navy," which got its start after Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, has stepped up to the plate once again, this time swooping in to help those in need in the neighboring state of Texas after Hurricane Harvey hit". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Szathmary, Zoe (12 September 2018). "Hurricane Florence prompts volunteer group America's Cajun Navy to send more than 1,000 people to help". Fox News. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ "America's Cajun Navy". America’s Cajun Navy. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Christopher (21 September 2018). "The Cajun Navy Heads To Help With Hurricane Florence". The Federalist. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Rescuing New Orleans – Nov./Dec. 2005

- ^ "You Want To Buy A What" - March/April 2004

- ^ Saving Lives Across America – August 2004

- ^ "Coast Guard Station Burlington Demonstrates New Airboat". Coast Guard News. Burlington, Vermont. February 13, 2010. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Rottman, Gordon L. (2007-09-18). Mobile Strike Forces in Vietnam 1966–70. New York: Osprey Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 9781846031397.

- ^ Kenneth Conboy, Kenneth Bowra, and Mike Chappell, The War in Cambodia 1970–75, Men-at-arms series 209, Osprey Publishing Ltd, London 1989. ISBN 0-85045-851-X. pp. 23

- ^ *Kenneth Conboy, FANK: A History of the Cambodian Armed Forces, 1970–1975, Equinox Publishing (Asia) Pte Ltd, Djakarta 2011. ISBN 9789793780863 pp. 239"

- ^ Floyd, Faron. "Whirl Wind Goes to Iraq". Whirlwind Propellers. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Airboatcapt2 (March 31, 2006). "Airboats in Iraq". Southern Airboat. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Airboats. |

- Motorboats

- Marine propulsion

- Boat types

- Canadian inventions